Brief opiate detoxification methods have proliferated rapidly and internationally. Conventional opiate detoxification takes about a week. However, with the newer methods it can be completed during the course of one day by using clonidine and opiate antagonists while the patient is under anesthesia (

1,

2).

The use of anesthesia eliminates the problem of dropout during detoxification, which is the fate of 15 to 30 percent of inpatients detoxified using conventional approaches (

3,

4). Medicaid data from New York State suggest dropout rates as high as 26 percent, which was the proportion of Medicaid-reimbursed detoxifications terminated against medical advice after an average of 4.4 days, suggesting that detoxification was not completed (

5). In New York alone, these patients cost Medicaid almost $30 million in 1995 (

5).

More than half of patients who complete conventional detoxification and enter an aftercare program return to routine opiate use within the first year (

6). Adjusting for an estimated 25 percent dropout rate during detoxification, it appears that no more than a third of patients who enter detoxification are opiate free one year later. Aside from addressing the problem of dropout, rapid detoxification may also encourage persons who are averse to conventional detoxification to detoxify (

7).

Unfortunately, few data exist on the efficacy of rapid detoxification (

8) aside from case reports (

1,

2). The study reported here investigated the one-year relapse rate of persons treated using one such protocol, the CITA (Center for Investigation and Treatment of Addictions) method, which is described in detail elsewhere (

9). This method is being practiced in several major teaching hospitals in the United States and abroad. It includes ultrarapid opiate detoxification combined with 15 counseling sessions and daily maintenance with 25 to 50 mg of naltrexone after detoxification for six to nine months.

Ultrarapid opiate detoxification is done in an intensive care unit under general anesthesia with intubation for six to eight hours using a combination of naltrexone, which blocks opiate receptors, and clonidine, a hemodynamic stabilizer. Patients at high risk for anesthesia-related complications are not treated. Most of the patients treated are in categories I and II of the American Society of Anesthesiology, indicating that anesthesia-related complications for planned procedures are extremely rare (

10). At the time of the study, the cost in U.S. dollars of ultrarapid opiate detoxification, including aftercare, was $4,500 and was not covered by insurance policies.

Methods

A sample of 120 male patients who were detoxified using ultrarapid opiate detoxification at least one year before March 1995 were randomly drawn from a list of 640 male patients. The study was conducted in Tel Aviv, Israel. A follow-up questionnaire was administered via separate telephone interviews to patients and significant others, usually family members. Considerable efforts were made to locate and interview respondents. Background information was extracted from structured patient intake records. Consistent with other studies of efficacy of detoxification and aftercare (

6), relapse was defined as a period of routine opiate use—at least two weeks of daily use—after detoxification. Patients who were judged not to have relapsed were those who did not return to a two-week period of routine use.

Of the 120 patients, seven were excluded because they lived overseas. Of the remaining 113 patients, the significant others of 19 could not be located, and two significant others refused to respond. Thus 92 significant others were interviewed, which represented an 81 percent response rate.

Eighty-three of the patients were interviewed, for a 73 percent response rate. One patient refused, and 29 could not be located. The sampling error for most questions, which involved percentages, was approximately 10 percent. The mean±SD follow-up time was 1.48±.19 years, with a range of 1.12 to 2.05 years. The only significant difference between the patients who were not interviewed and those were interviewed was that more time had elapsed since detoxification (mean±SD=1.63±.18 years for those not interviewed and 1.48±.19 for those interviewed; t=3.2, df=108, p=.002).

Results

Based on the responses of patients and significant others, 36 patients (43 percent) had relapsed in the year after detoxification, and 47 patients (57 percent) had not relapsed. Although significant others were blind to patients' responses, in all cases their responses about the extent of opiate use matched those of patients. Fourteen of the patients who did not relapse reported episodic use of opiates—seven patients in the seven months after detoxification. Specifically, two nonrelapsing patients used opiates within the first week, one at three months, three at four months, one at six months, six at eight months, and one at 12 months.

The 36 patients who relapsed reported first use of opiates considerably earlier. By the end of the second month after detoxification, slightly more than half had used opiates. Five patients used opiates immediately following detoxification, another four during the next two weeks, nine more during the next two months, three in the third month, five in months 5 to 7, and eight during months 8 to 12. Information for two of the patients was unknown.

The patients who relapsed differed from those who did not in that a greater proportion of the relapsing patients had been spent time in jails or prisons in their lifetime (74 percent, or 25 patients, versus 41 percent, or 19 patients; χ2=8.2, df=1, p=.004), and fewer of the relapsing patients had worked during the year before detoxification (18 percent, or six patients, versus 55 percent, or 26 patients; χ2=11.7, df=1, p=.001).

These two variables were entered into a logistic regression equation to predict relapse. Patients who had been incarcerated were three times more likely to relapse than those who had not (odds ratio=2.9, confidence interval=1.2 to 6.8). Patients who worked during the year before detoxification were four times less likely to relapse than those who had not worked (OR=.23, CI=.09 to .58).

No significant differences were found between the patients who relapsed and those who did not in age at first drug use (mean±SD=17.7± 4.5 years for the entire sample of 83 patients), age at the time of the index detoxification (mean±SD=32.9±5 years), years of formal education (mean±SD=9.8±2.1), marital status (single, 36 percent, or 29 patients; married or living together, 51 percent, or 41 patients; divorced or separated, 13.6 percent, or 11 patients; and unknown in two cases), previous mental health treatment (16 percent, or 13 patients), the number of previous detoxifications (mean±SD=2.8± 2.2), arrest history (78 percent, or 61 patients; data missing in five cases), and the extent of contact with other services after detoxification. A total of 69 patients (83 percent) reported having no contact with other services.

Few patients in either of the groups reported using other substances. Among patients who relapsed, one each reported using marijuana, alcohol, stimulants, and sedatives. Four of the patients who did not relapse reported marijuana use, and two reported alcohol use.

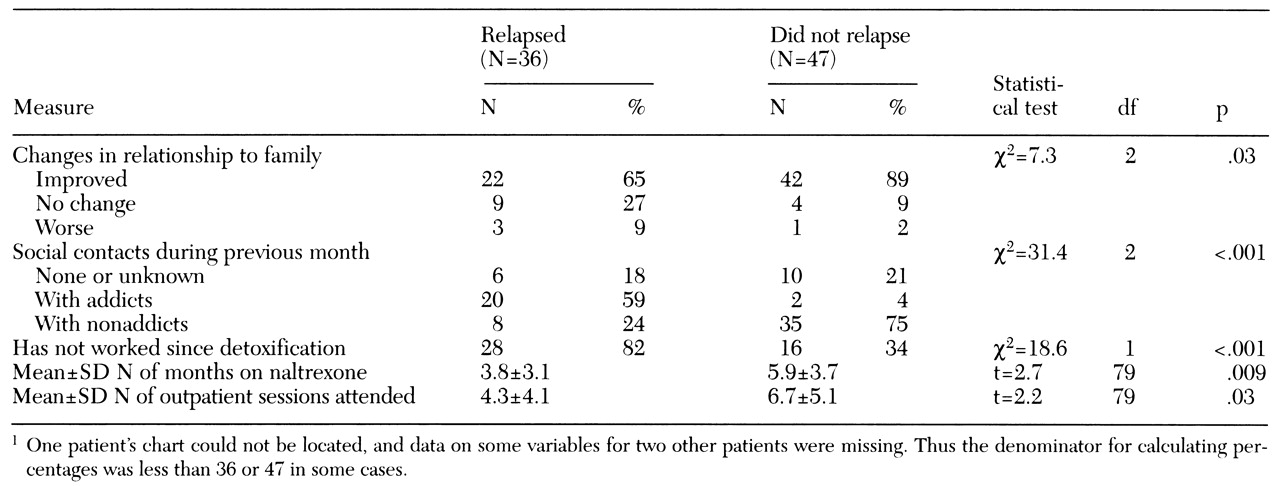

Table 1 presents other outcome measures. After detoxification patients who relapsed had significantly less improvement in family relationships and more social contacts with addicts than those who did not relapse. Fewer of the relapsing patients had jobs, and they used naltrexone for fewer months and attended fewer outpatient sessions.

Discussion and conclusions

Rapid opiate detoxification under general anesthesia appears to offer an advantage because there is essentially no dropout from detoxification. The follow-up results obtained from patients one year or more after detoxification were better than those obtained in studies of other detoxification methods. Those studies used similar measures and a similar definition of relapse, but they did not adjust for dropout during detoxification, which would have further reduced their success rates.

Because those studies focused primarily on publicly funded programs, comparison with this study is limited. Patients in this study paid for treatment with private funds and thus may have been more motivated and of higher socioeconomic status. However, the patients in this study appear to be similar to many patients treated in publicly funded substance abuse programs. For example, almost 80 percent had been arrested, more than half had been imprisoned, and on average they had almost three previous detoxifications.

The results of this study indicate that ultrarapid opiate detoxification may be effective for other opiate-addicted persons. The high level of agreement in reports of substance abuse between patients and their significant others, while not conclusive, supports the validity of self-reports of substance abuse, as found in other studies (

6). Ultrarapid opiate detoxification combined with naltrexone maintenance and counseling should be tested relative to conventional methods in random-assignment controlled trials that include laboratory toxicology tests.