Voluntary hospitalization is the cornerstone of inpatient psychiatric treatment, accounting for the majority of episodes of hospital-based care in the United States (

1). Among the generally accepted benefits of voluntary admission are its greater simplicity, the avoidance of unnecessary restrictions on patients' liberty, and a greater level of involvement by patients in treatment, based on their acceptance of responsibility for making decisions about their own care (

2). These beliefs have led some states to require that all patients be offered the option of voluntary hospitalization, even those who might otherwise qualify for involuntary commitment (

3).

However, clinicians and policy makers have long been concerned about the capacities of persons suffering from acute mental disorders to make decisions about hospitalization. Indeed, it was because of these doubts that the first statute in this country authorizing voluntary hospitalization was not adopted until 1881, more than a century after the first psychiatric admission occurred (

4).

More recently, legal advocates have claimed that incompetent patients have been induced to surrender the greater procedural rights afforded involuntarily committed persons by signing voluntary admission forms (

5). These concerns have been stoked by several decades of research using relatively demanding tests that suggest that many voluntary patients—the percentage varying depending on the population studied—may lack substantial awareness of the consequences of hospitalization (

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11).

Renewed attention has been paid to questions of voluntary patients' capacities to consent to hospitalization in the aftermath of the U.S. Supreme Court's 1990 decision in

Zinermon v. Burch (

12). Darryl Burch, a Florida man, had been hospitalized voluntarily while in a psychotic state; a contemporaneous note indicated that he thought he was entering "heaven." Although the court decided that Burch had been deprived of his rights by being allowed to make an incompetent admission decision, the holding was based on an interpretation of Florida's statute and thus was not necessarily applicable to other states. However, the court's opinion included nonbinding language suggesting that patients' constitutional rights might be violated if their competence was not determined before voluntary psychiatric hospitalization and if incompetent patients were allowed to sign themselves in.

Zinermon raised anxieties among state mental health administrators and clinicians, who were unsure how to respond. Clear criteria for assessing competence to consent to hospitalization did not exist, and a broad interpretation of

Zinermon seemed to call for an extended screening process before each voluntary admission, an awkward and costly procedure. Moreover, no one had an answer to the question of what to do with patients who sought admission and were not considered competent to sign themselves into the hospital, but did not qualify for involuntary commitment. Clinicians were troubled by the prospect of turning away from the hospital's doors this most disabled group of patients (

13).

In response, the American Psychiatric Association established a task force on consent to voluntary hospitalization. The task force's 1993 report pointed to the general societal interest in allowing patients to seek care voluntarily and suggested such admissions might best be accomplished by establishing a low threshold for competence to consent to hospitalization (

2). It proposed that the required capacities be limited to the abilities to communicate a choice and to understand relevant information.

The two categories of information deemed to be relevant were that the person "is being admitted to a psychiatric hospital or ward for treatment" and that "release from the hospital may not be automatic, and he or she can get help from the staff to initiate procedures for release." The task force noted its belief that "this threshold for capacity is lenient but meaningful, set at a level which most patients currently admitted on a voluntary status would pass."

However, the only study to date related to the task force's proposal calls that conclusion into question. Poythress and colleagues (

14) assessed 120 patients who were initially brought to two Florida facilities on an involuntary basis, including 60 patients who signed themselves in voluntarily 72 hours later, and 60 who did not. The researchers used the Measuring Understanding of Disclosure —Voluntary Hospitalization (MUD-VH), an instrument designed by the second and third authors of this paper, to approximate the capacity standard endorsed by the task force.

The format for the MUD-VH was based on instruments used in a large-scale study of patients' capacities to make treatment decisions (

15). It is scored on a scale from 0 to 4. Of the voluntary patient group in the study by Poythress and colleagues, 41.6 percent scored 2 or less, as did 28.4 percent of the involuntary group. Thus the data suggested that a large proportion of patients might have impaired capacities to consent to their own hospitalization, even when capacity was measured with a test that reflected the lenient APA standard.

However, the Poythress study used a selected population, atypical of most voluntary patients. The subjects were all originally detained involuntarily and were likely to have been more symptomatic than patients who initially sign into the hospital voluntarily. Moreover, the authors themselves noted that the cued-recall format of their questions might have resulted in worse performance than could have been obtained with a multiple-choice recognition format.

The study reported here was designed to provide a test of the effect of the APA proposal with a more representative population of voluntary patients and to use both cued-recall and recognition questions.

Methods

Every patient signing voluntary admission papers at the time of or following hospitalization at either of two University of Massachusetts Medical Center psychiatric inpatient units over a one-month period during the summer of 1996 was eligible for the study. Of 137 eligible patients, 100, or 73 percent, were interviewed; these patients constitute the sample reported on below. The remainder were excluded from the study for the following reasons, in order of frequency: they were unable to speak English, they were admitted and discharged over a weekend, they refused to take part, or their physicians considered them too aggressive or unstable to participate. The first author approached patients within five days after they had signed voluntary commitment papers (mean=1.13 days). After he obtained written informed consent from the patient, demographic information, social history, and current diagnosis were obtained from the patient and the patient's chart, and the MUD-VH was administered, all in a single session lasting about 15 minutes. (A copy of the MUD-VH is available on request from the authors.)

The MUD-VH consists of two brief paragraphs that disclose information about voluntary psychiatric hospitalization. Each of the paragraphs is followed by a series of questions. The version of the instrument used in this study included questions that asked patients to recall the information provided in the paragraphs and true-false items that tested patients' recognition of the information. All information and questions were read aloud while the patient followed on a copy of the instrument.

The first paragraph details three purposes of psychiatric hospitalization: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of harm to self or others. The second paragraph explains that discharge from voluntary psychiatric hospitalization is not automatic; patients may be released, or they may be kept by doctors if the patients are perceived as posing a threat to themselves or others. The instrument's readability was measured at the 8.3 grade level on the Flesch Readability Scale. After each paragraph was read to the patient, two sets of questions, one testing recall of the presented information and the other testing recognition in a true-false format, were read. Incomplete or ambiguous answers were followed up by the interviewer with open-ended queries, until it was clear that no further data could be obtained.

Each of the four sets of questions was scored on a 3-point scale. The recall section of the first question was scored 0, 1, or 2 for recalling up to one, any two, or all three of the purposes of hospitalization, respectively. On the recognition section, which consisted of six true-false items, three or fewer correct answers (the number expected by chance) received a score of 0, four correct answers received a score of 1, and five or more correct answers received a score of 2.

The second question was scored similarly, with the recall section scored 0, 1, or 2 based on whether subjects recalled none, one, or both of the courses of action available to the hospital should they desire to leave. On the recognition section, which had three true-false items, one or no correct answers received a score of 0, two correct answers were scored 1, and answering all three questions correctly resulted in a score of 2. A fourth true-false item that had been administered to subjects was not scored, because it was clear from subjects' responses that it had been framed in a misleading fashion.

Results were analyzed for each item and for each question as a whole. The recall and recognition section scores for each of the two questions were totaled for a question score of 0 to 4. In addition, overall recall and recognition scores were calculated by adding the respective sections from each half, also resulting in a range from 0 to 4. Statistical comparisons of scores for patients grouped by various demographic and clinical variables were made using chi square and one-tailed paired t tests, with a significance level of p<.05.

Results

Fifty-nine of the subjects who were interviewed were female, and 41 were male. Their mean±SD age was 38.2±12.6 years. Eighty-one subjects were white, eight were African American, eight were Hispanic, and two were Asian. The subjects had completed a mean±SD of 11.5±3.5 years of education.

Subjects reported a mean±SD of 8.06±10.8 previous hospitalizations. Twenty patients reported 12 or more previous hospitalizations; the mean± SD number of hospitalizations for this group was 27.6±9.4. Only 20 patients indicated they had never been hospitalized previously.

Eighty-seven percent of subjects signed a voluntary commitment paper on admission. Of the 13 percent who signed the voluntary commitment paper later during their hospitalization, six signed four or more days after admission. An average of 1.1±1.3 days elapsed between signing of voluntary papers and administration of the questionnaire: 76 patients were interviewed within 24 hours of signing, and 86 patients within 48 hours.

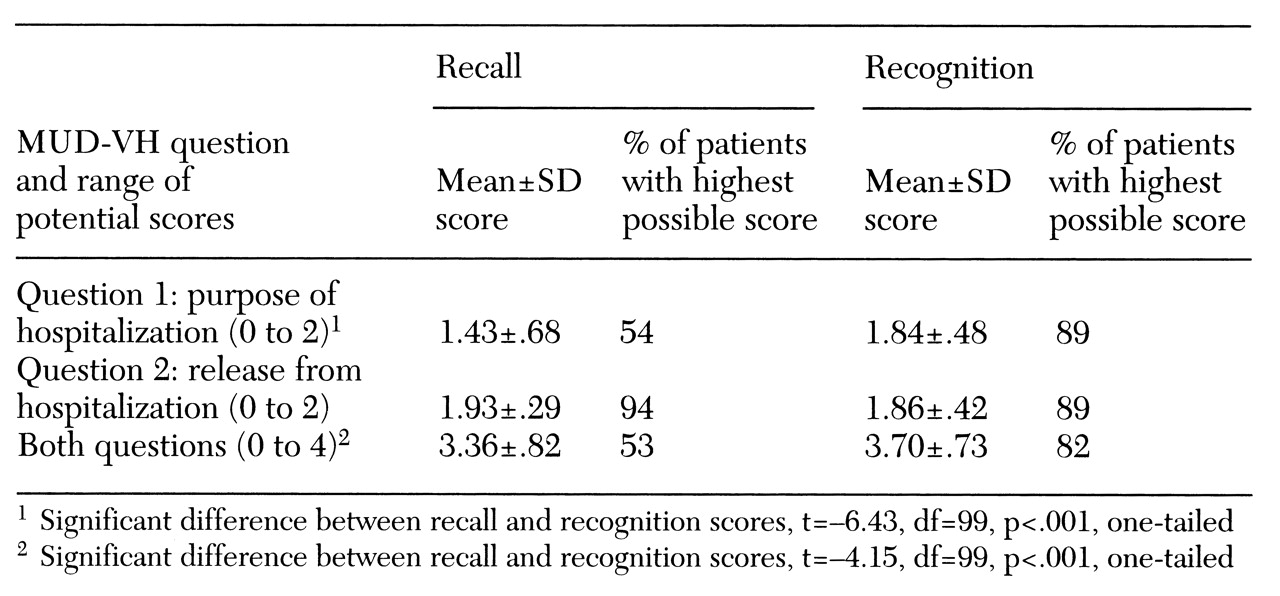

The results of the MUD-VH questions are shown in

Table 1. Subjects showed significantly better performance on the recognition (true-false) task, compared with the recall task. This difference was entirely due to improved performance on question 1, dealing with the purposes of hospitalization. Most subjects (83 percent) were able to recall treatment as a purpose of hospitalization, but only 35 percent recalled diagnosis and 41 percent prevention of harm. Correct responses for the latter two questions in the recognition task increased to 92 percent and 97 percent, respectively. On question 2, which addressed the possibility of detention after the patient made a request to leave the hospital—arguably the most important piece of information of which voluntary patients should be aware—subjects achieved nearly perfect scores even on the recall task.

In the analysis of the scores of patients grouped by the independent variables, patients who signed themselves in on admission, rather than later during hospitalization, performed significantly better on question 1 in both recall and recognition formats and on question 2 in recognition format. They also had significantly better total scores on recall and recognition. Less robust, but still significant, differences were seen on several subitems among patient groups with increased age and with a large number of previous admissions (more than 12 admissions), each of which had a detrimental effect on performance.

There were no significant differences in scores by gender. The small percentage of nonwhites made it impossible to gauge the impact of race.

Discussion and conclusions

This study investigated the capacity of persons who signed voluntary commitment papers to comprehend the nature and implications of their actions. In contrast to previous studies, which reported generally pessimistic conclusions, the data presented here support the notion that most patients seeking voluntary hospitalization can pass a low-threshold test of capacity. Even on the more difficult task of recalling information, almost all patients (94 percent) were able to provide information about the limitations on their freedom to leave the hospital at will—arguably the most important datum at issue.

When comprehension was tested using the easier format of information recognition, patients performed significantly better on the question addressing reasons for hospitalization, with a large majority (89 percent) achieving scores that indicated good comprehension. That 82 percent of subjects achieved perfect scores on both questions on the recognition (true-false) format offers the most encouraging picture yet of the performance of voluntary patients on more lenient measures of competence.

Our findings contrast with those of Poythress and associates (

14), who demonstrated patients' poor ability to respond to questions about disclosed information. The differences between the studies appears to be due largely to two factors. First, as Poythress and colleagues suggested and as our data confirm, patients have greater difficulty with recall than with recognition tasks. Second, the sample that Poythress and associates chose for their study—patients who signed papers for voluntary commitment after involuntary admission—seems to be particularly at risk for impaired capacity. It was precisely this variable that correlated most strongly in our study with decreased performance on both recall and recognition tasks. Yet, most voluntary patients (87 percent in our sample) do not first enter the hospital involuntarily, and thus data from the initial involuntary group cannot be extrapolated to the larger group of voluntary patients.

One of the most important implications of the two studies, however, derives directly from the difference between the two groups. Because patients initially admitted on an involuntary basis may be at particularly high risk of impaired capacity to consent to voluntary hospitalization—in contrast to those signing voluntary papers at the time of admission—the former group may warrant genuine concern. Fortunately, it should be possible to focus attention on them precisely because they are already in the hospital when the decision for voluntary admission is being made. In their relatively protected situation, careful examination of capacity and increased educational efforts to inform them about the consequences of a change in their legal status can be undertaken.

Furthermore, concern that patients who lack capacity to consent to voluntary hospitalization and are unsuitable for involuntary commitment will slip between the system's cracks are inapplicable to this group. If they fail to meet standards for consent to voluntary commitment, they can be allowed to remain in the hospital on involuntary status.

Of lesser impact in our study were two other variables: older age and chronicity of condition. These factors both impaired patients' ability to comprehend the information presented to them. People being admitted with these characteristics may need more careful attention, repeated explanations, and other appropriate measures for ensuring their comprehension of the voluntary admission status.

Whether the low-threshold standard for consent to voluntary hospitalization suggested by the APA task force is the proper level of required capacity is a normative judgment that cannot be determined by an empirical study such as ours. Moreover, whether cued recall or recognition of information better demonstrates a person's ability to use information in a decision-making process is an issue about which cognitive psychology itself has not yet reached closure. However, the data presented here suggest new grounds for optimism about patients' comprehension of voluntary commitment as measured by low-threshold measures of capacity, particularly when tested in recognition format. Much of the residual poor performance on this standard may be addressed by targeting high-risk populations—including those who initially enter the hospital involuntarily—for additional educational interventions.