The proportion of children living with grandparents in the U.S. has increased dramatically over the last decade. Five percent of all American children were living with grandparents or other relatives in 1990, and in one-third of these homes, neither parent was present (

1). In 1993 a total of 3.4 million children were living with grandparents, a 46 percent increase from 1980 (

2).

The National Survey of Families and Households, conducted by the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison between 1992 and 1994, included 3,477 custodial grandparents (

3). Of these respondents, 54 percent were married and 77 percent were women. Sixty-two percent were non-Hispanic white, 27 percent were African American, 10 percent were Hispanic, and 1 percent were classified as "other." The mean age of these custodial grandparents was 59.4 years.

The increase in the number of children being placed under the care of their grandparents has been attributed to various factors, including parental substance abuse, teenage pregnancy, divorce, unemployment, HIV infection, and violence (

4,

5). One can speculate that these children are likely to experience more stress and emotional problems than other children due to separation and loss of parents, neglect, abuse, and the limited abilities of grandparents. If these children do indeed have more emotional problems, they could benefit from specialized treatment approaches. However, very little research has been done to address these speculations.

This paper reports findings from a pilot study involving emotionally disturbed children who live with their grandparents. The study was prompted by the first author's observation that a large number of children treated in an urban community mental health center were being cared for by their grandparents and his subsequent interest in examining whether these youths were different from the other children who came to the center. The goals of the pilot study were to determine the demographic and clinical characteristics of the youths to help in understanding and treating them better and to point to areas in need of further study.

Methods

The data were gathered through a chart review of all active child and adolescent patients at the Walter P. Carter Center, a community mental health center affiliated with the University of Maryland in Baltimore. The review was conducted over a week in the spring of 1998. The center provides outpatient psychiatric services to children and adolescents age five through 18. It is located in an inner-city area and serves mostly low-income families.

Clinicians were asked to identify from their caseload children and adolescents who were under the care of their grandparents. For each youth, data on demographic characteristics, historical information, and DSM-IV primary diagnosis were obtained from records of psychiatric evaluations. Information about possible reasons for the placement of the youth with the grandparents was obtained from records on family history. An attempt was made to collect information on all possible reasons related to both biological parents.

Results

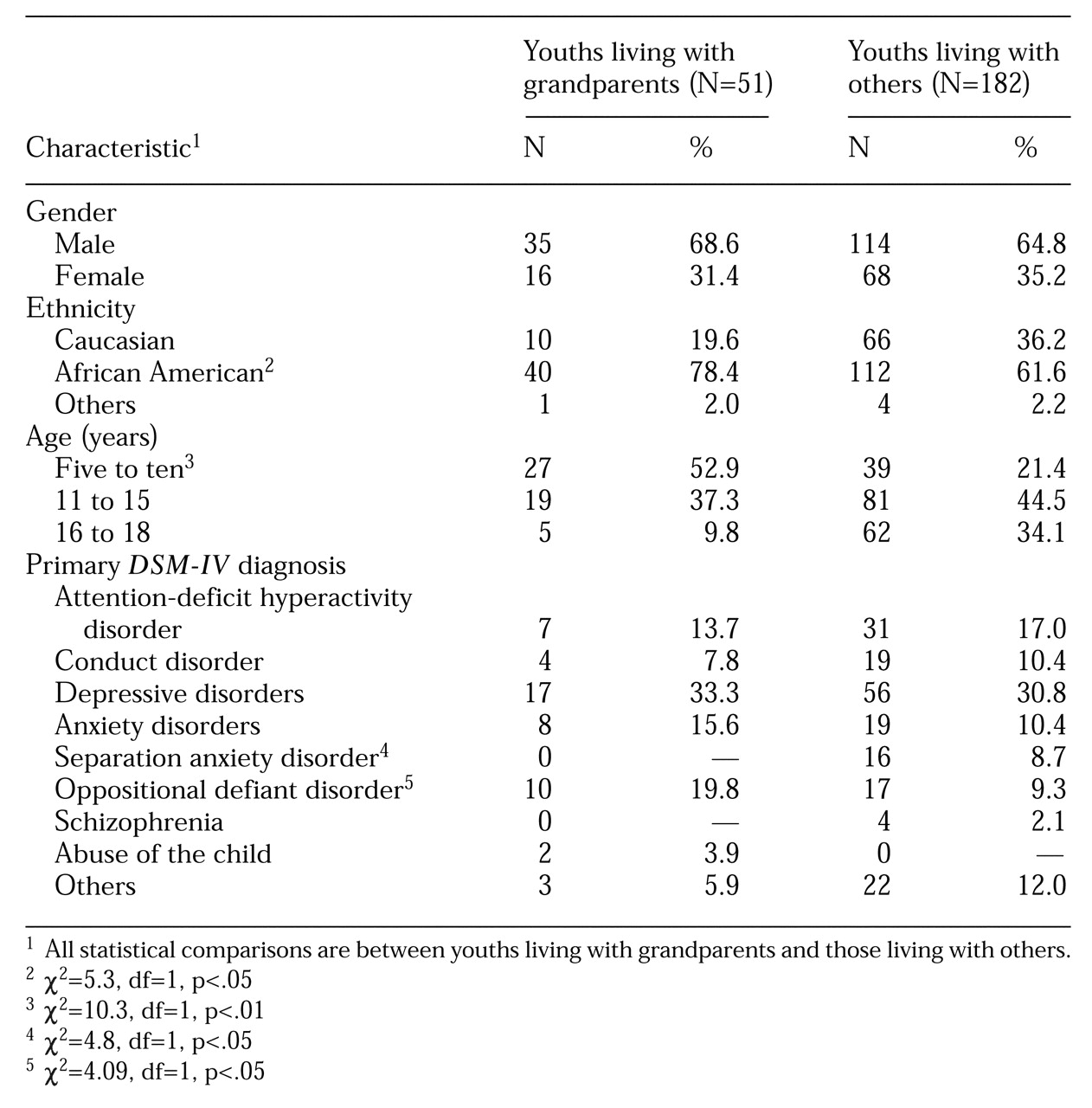

At the time of the chart review, 233 children and adolescents were in active treatment at the center. Fifty-one of these children, or 21.9 percent, were living with their grandparents. The demographic characteristics and diagnoses of youths living with grandparents were compared with those of youths who lived with someone other than their grandparents.

The mean±SD age of subjects was 10.9±3.4 years, with a range of five through 18 years. As

Table 1 shows, youths who were living with grandparents were more likely to be in the younger age bracket (ages five to ten) than youths living with others. Youths living with grandparents were also more likely to be African American.

As for DSM-IV primary diagnoses, compared with youths living with others, youths living with grandparents were more frequently given the diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder and less frequently given a diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder.

In terms of their living situation, ten subjects lived with both grandparents, 39 lived with their grandmother only, and two lived with their grandfather only. The majority of these youths were living with maternal grandparents (44 youths, or 86.3 percent) rather than with paternal grandparents (seven youths, or 13 percent). The mean±SD age of the grandparents was 57±10.3 years, with a range from 41 to 88 years. The majority of the grandparents—22 grandmothers, or 44.9 percent, and six grandfathers, or 50 percent—were between 51 and 60 years old. The next most common age range for grandparents was 41 to 50 years; 12 grandmothers, or 24.5 percent, and four grandfathers, or 33.3 percent, were in that age range.

The records often showed multiple reasons for placement of a youth with the grandparents. The most common reasons for placement were that the parent was absent or unavailable (44 youths), parental substance abuse (36 youths), substance abuse and incarceration (17 youths), abuse by parents (15 youths), and death of parents (seven youths).

Discussion and conclusions

In this pilot study we found that 22 percent of a sample of 233 youths attending an inner-city community mental health center for treatment of emotional or behavioral problems were being cared for by their grandparents. This proportion is much higher than the 5 percent of all children living with grandparents that was reported in a national survey (

1). However, due to a lack of studies of youths living with grandparents, it is difficult to speculate on reason for the very high percentage found in this pilot study.

We also found that a disproportionate number of youths who were living with their grandparents were African American. This finding is consistent with literature indicating a more prominent role of black grandparents in providing surrogate parenting (

6). It also highlights the need for clinical training to allow mental health staff to provide culturally sensitive services to these important caretakers.

The majority of the youths who lived with their grandparents were in the younger age group (five to ten years old), and the majority of youths who lived with others were a bit older (11 to 15 years old). This finding supports the idea that as children get older, grandparents are less likely to be their caretakers. Further research is needed to determine whether grandparents are less likely to be involved in care as children age because older children and adolescents present behavioral challenges that grandparents cannot handle.

Youths living with grandparents were more frequently given a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder than were youths living with others. The factors associated with the elevated frequency of this disorder are difficult to tease out. They may include youth-related factors such as challenging behavior, factors associated with the grandparents (for example, lax supervision), and interactive factors. In contrast, we were surprised by the finding that youths living with their grandparents were less likely to be given a diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder than were other youths. This finding is difficult to interpret, given the lack of research about youths who are living with grandparents. The finding may reflect a positive effect of being raised by grandparents, who may offer a more secure and stable living situation in the inner-city environment than younger adults are able to provide.

The limitations of this study include its reliance on chart review and use of clinical psychiatric diagnoses that were not confirmed by the researchers. In addition, because data were collected from only one community mental health center, anomalous qualities in the sample cannot be ruled out. Thus conclusions from this study must be considered preliminary.

Given the dearth of research on children living with grandparents, we hope that this pilot study calls attention to the needs both of these children and of their grandparents. Further research is needed to substantiate the extent of the problem across communities of varying sociodemographic and cultural backgrounds and to explore the reasons for elevated behavioral problems among these youths.