Measurement

More than 30 years ago, Donabedian (

28) conceptualized measurement of quality as focusing on three components: structure, process, and outcome. Structural measures examine credentials, rules, regulations, and accreditations. Process variables measure how providers accomplish their goals through prevention, screening, diagnosis, psychological and physical treatment, and rehabilitation. Outcomes measurement looks at short- and long-term results of the process interventions in the structural environment.

Quality can also be assessed by examining adherence to standards or by using scorecards. A discussion of the use of standards or treatment guidelines to measure and improve quality is beyond the scope of this paper. Besides the creation of guidelines, national efforts in the area of quality assessment have also focused on a search for a critical set of indicators for use in a scorecard that accurately and reliably measures the quality of care. Assuming that one of the primary objectives of a practitioner or organization is to meet patients' needs and expectations, quality indicators that reflect this objective and lead to the desired outcomes must be selected. A system cannot realistically track and use all the available indicators, nor is such a course useful or necessarily reflective of a chosen objective. In the final analysis, the selected indicators must allow for the evaluation of the system's or practitioner's ability to meet patients' needs and expectations (

29,

30).

The proper choice of indicators, especially the judicious choice of a few, is a major and daunting task. Organizations require very specific indicators that measure whether they achieve their objectives. The design of a quality measure, or indicator, is important to its effectiveness. Eddy (

31) proposed five characteristics of a good indicator: purpose, target, dimension, type, and intended user.

Eddy also identified three potential purposes of an indicator—to determine the effect of an intervention on a group of individuals (outcome studies), to assess the impact of a change in a treatment or process, and to reveal differences in quality between two organizations such as hospitals or health plans.

The target—the entity being assessed, such as an outpatient clinic or the inpatient unit in a hospital—can also influence choices and design of indicators. All variables—for example, the insurance coverage or the support systems of the patient being treated—may not be under the control of a clinic or hospital. A measure must also identify the dimension being assessed, such as the extent of coverage of care or the extent of choices of providers.

The fourth characteristic of a good performance measure, or indicator, is the ability to reflect the different components, or variables, that led to a particular outcome. For example, medication-error rates reflect the quality of a nursing and pharmacy staff. On the other hand, rates of recovery from a depressive disorder reflect not only how good the pharmacy and nursing staff are but also the quality of the physicians, therapists, and any other aspect of the treatment process.

Quality indicators can be divided into six categories (

32). Indicators related to patients' encounters with the system of care measure service quality, appropriateness of care, clinical outcomes, and functional status outcomes. Indicators that measure accessibility of care look at the system's capacity, the availability of clinicians, timely access, and geographic issues. The other four categories of indicators are prevention and screening, disease management, enrollee health status, and population health status. Ideally, the heath status of the population within the health care organization's service area reflects the long-term beneficial effect of the organization's preventive and acute-care interventions.

Finally, according to Eddy, it is important to identify the users of the performance measures. Patients, payers, employers, and policy makers have different needs and levels of sophistication. The performance indicators chosen must be of significant utility to these users to justify the cost of measuring these aspects of care.

To help in the task of choosing indicators and measuring performance, a solid and well-funded information system is critical (

33). For systems that do not want to develop their own system of quality indicators and measurement tools, many are available for purchase.

Scorecards

In the past, quality indicators focused mainly on two aspects of care, clinical and financial. Clinically, the emphasis was, and still is in many instances, on perfecting the provider's performance so that errors and mistakes were reduced. The focus was on the outlier—the provider that fell outside of the norm—with little regard for the context or for adjustments for case mix and severity of illness. An organization's performance was measured against a standard set by a national organization such as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, NCQA, and the Rehabilitation Accreditation Commission.

Financially, the quality measurement process reflected the performance of an independent entity, such as a psychiatric inpatient unit or an outpatient clinic, and used balance sheets and income statements.

Simply identifying, compiling, and tracking a set of indicators, however judiciously chosen, may not lead to desired objectives and may not result in a useful set of measurements. With the ever-expanding search to identify indicators of quality for health care in general (

34), and of mental health services in particular (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12), a fundamental question is raised: what will be the utility of indicators based on their purpose, acceptability, effectiveness, and impact? In other words, beyond identifying key characteristics and variables that indicate high-quality performance by a mental health system, how are they to be used effectively and toward what end?

A method to implement strategies for ensuring the provision of high-quality care is needed. An instrument is required to link the desired objectives to the indicators, at multiple levels and in a variety of areas. No method is currently available to understand how the choice of indicators influences the system of care and how the indicators measure the critical results.

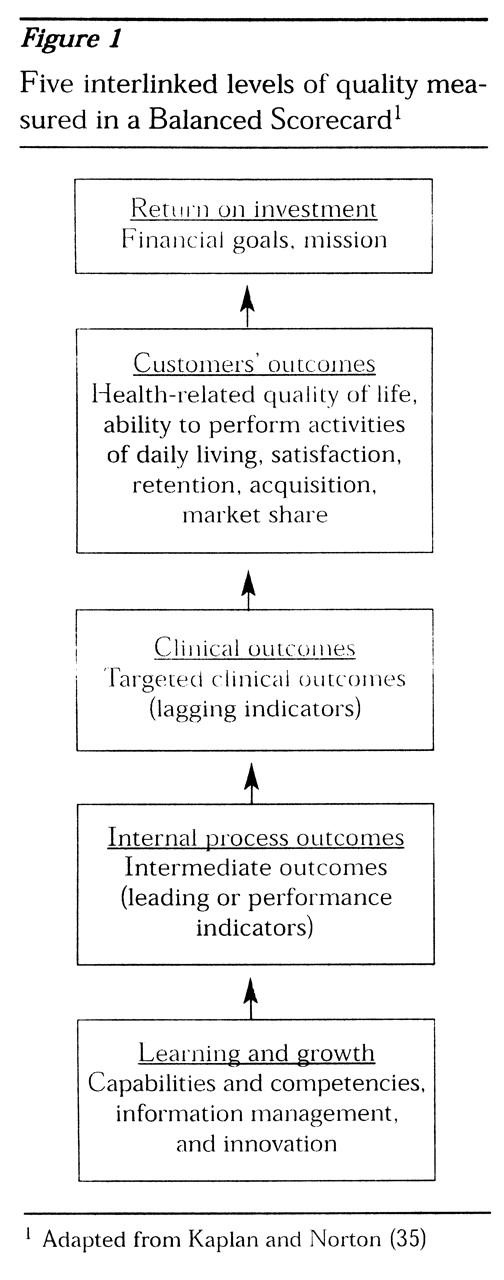

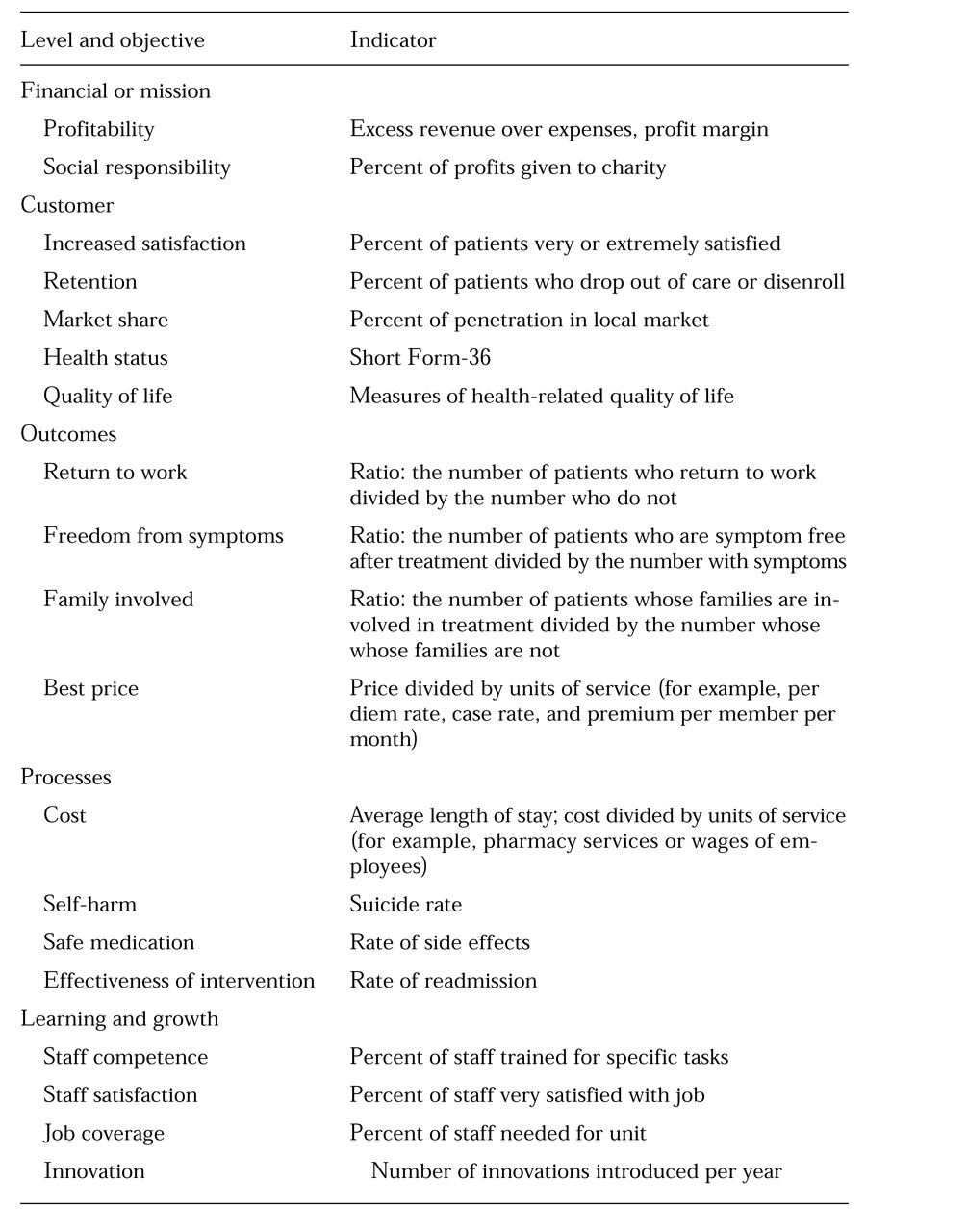

Kaplan and Norton (

35) have proposed the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) for business industries as a tool to implement a strategy as well as to measure its effectiveness. Use of the BSC requires the organization to identify and balance external measures of quality for customers and internal measures of the organization's critical delivery processes, innovation, and learning and growth. The BSC should combine measures of past performance with measures of what drives future performance.

Kaplan and Norton (

35) consider four perspectives on quality, with corresponding indicators. Applied to behavioral health care, these perspectives are financial; customer, such as patient, family, payer, and employer; internal processes, such as clinical outcomes; and learning and growth, such as the capability and competency of individual clinicians, the adequacy of information systems, and the provider's ability to innovate. According to Kaplan and Norton, to be effective and yet manageable, a BSC must not exceed four or five indicators for each perspective, for a total of 20 to 25 indicators tracked closely.

Each of the four sets or levels of indicators forms a chain of cause-and-effect relationships. For example, improvements in clinicians' skills, which are at the level of organizational learning and growth, result in higher-quality delivery of care, which is measured by intermediate or final clinical and functional outcome indicators. The result is a service provided to the patient, the patient's family, the payer, and the employer, who develop customer loyalty based on the perceived quality of the services and the product. Customer loyalty is measured by satisfaction, customer retention, and market share. Finally, customer loyalty is reflected in a desirable financial return, measured by financial indicators such as profit and loss.

The quality measures at each level must be understood as a function of the objectives at that level. Financial return indicators are a measure of the organization's financial objectives. However, understanding patients' objectives—their needs and expectations—may not be as easy as understanding financial objectives. Research on patient satisfaction, intuitively the measure closest to needs and expectations, has not yielded the expected information (

34).

In this respect, it is important to distinguish between the quality of the service, which can be measured as the attentiveness of providers to patients' needs and expectations (for example, the quality of the "hotel" functions of a hospital) and the quality of the product—that is, whether the patient improved and was able to avoid death, disability, discomfort, and disease. The quality of such services as food, parking, and cleanliness are predominant in satisfaction surveys; however, patients do not equate the quality of these services with quality of care.

The notion of satisfaction is itself subject to interpretation. One can assert that an expectation has been met when a patient is satisfied, but what about need? Low-quality care may be acceptable to patients, while high-quality care may not. For example, a patient may be more satisfied when treated with an antidepressant medication rather than electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), even when the patient's profile clearly indicates ECT as the treatment of choice. Finally, being treated with respect and being permitted to maintain one's dignity, aspects of care that are not often addressed in satisfaction questionnaires, may be paramount in patients' definition of quality (

24).

Clinical and functional outcomes can be understood by examining the difference between process measures, or what happened during the intervention, and outcome measures, or the patient's health-related quality of life before and after treatment. In the BSC, performance is measured by process indicators, also referred to as leading indicators. On the other hand, outcomes do not necessarily reflect performance but simply results. The latter are also referred to as lagging indicators. A patient's improvement, as measured by a lagging indicator, may occur as a result of or in spite of the process used by a clinician, which is measured by a leading indicator.

The challenge may lie in linking health-related quality of life to quality of care. In health care, several factors seem to be required for a link between a specific outcome and a particular process. It is important to identify a well-defined group of medical conditions or demographic characteristics, or both, and a well-accepted physiological, biochemical, or psychological mechanism linking the medical intervention with the outcomes targeted for the medical condition (

24). For example, bipolar disorder can be considered a well-defined medical condition. The interventions that have been used to treat bipolar disorder have centered on several hypotheses. Currently, hypotheses that are based on the inhibition of neurotransmitters and neuroreceptor processes seem to have widely accepted support. Mood stabilizers, lithium, and anticonvulsants are the preferred medical interventions, reflecting the link between these hypotheses and medical outcomes.

To assess quality, it is necessary to use leading indicators, which are performance drivers such as relapse rate, side effects, and suicide rate, and lagging indicators, which are outcome measures such as recovery rates, functional levels, work productivity, and prevention of disease. Measuring performance drivers without measuring outcomes may prevent the assessment of an organization's or provider's success in the marketplace. One patient may not relapse to depression and another may stop making suicide attempts, but these outcomes do not indicate whether the patients were able to return to full employment and to the enjoyment of a fulfilling life. Knowing that a patient recovered from a psychotic episode tells us what happened, an outcome or lagging indicator, but not why or how it happened, a performance or leading indicator.

As developed for business organizations, the BSC was originally structured with four levels. However, I would propose adding a fifth level—clinical and financial outcomes—implicit in Kaplan and Norton's customer level (

35), but useful as a separate and distinct category in health care. The four other levels are internal processes, clinical and financial outcomes, measures related to the customer, and financial measures.

• Learning and growth measures include professionals' competencies, capabilities, skills, and availability. They track the sophistication and accessibility of information systems and assess innovation initiatives.

• Internal process measures focus on intermediate functional, clinical, and financial outcomes such as length of stay, morbidity, complications, side effects, use of restraints, response time, and cost per unit of service.

• Examples of clinical and financial outcomes include recovery measures, mortality, and price per unit of service.

• Customer measures include those directly relevant to patients, families, payers, and employers. Examples are health-related quality of life, functional level, the ability to perform activities of daily living, satisfaction, and market retention, acquisition, and penetration.

• Financial measures include return on investment and economic value added (profitability or return on investment). In not-for-profit organizations, positive revenue over expenses is measured.

The cause-and-effect links between these five levels of indicators are represented in a sequential diagram in

Figure 1.