The mentally disordered offenders program of the Isaac Ray Center in Chicago was established in 1978 to provide evaluations and outpatient treatment for individuals who are adjudicated as not guilty by reason of insanity but who are not, or are no longer, in need of hospital-based psychiatric treatment. The center's treatment goals are to reduce the potential for future violent behavior, to work toward remission of psychopathology, and to help potentially violent individuals, all of whom have serious psychiatric illnesses, develop healthy and responsible interpersonal relationships (

1).

The purpose of specialty forensic community programs such as ours is to reduce or eliminate the potential for criminal recidivism by accurately diagnosing and treating psychiatric illness. These clinical services are provided in the least restrictive setting. Basic principles of mandated community treatment for offenders with mental disorders have been reviewed by Wasyliw and associates (

2).

The term "mentally disordered offenders" describes persons who have been charged with, although not necessarily convicted of, a crime and who demonstrate a mental disorder that affects how they are dealt with by the criminal justice system (

3). These individuals have been labeled as both "mad" (mentally ill) and "bad" (socially deviant) (

4). Often they demonstrate violent behavior, and therefore treatment of their psychopathology must recognize the potential for aggression and hostility.

Offenders with mental disorders who have been adjudicated as not guilty by reason of insanity are at special risk for committing violent acts. For this group, assurances of crime-free management is a particular concern. The term "not guilty by reason of insanity" applies to persons found to be legally insane and therefore not criminally responsible at the time they committed their alleged offense (

5). They are adjudicated as having committed crimes while mentally disordered. Their past histories of dangerous behavior further distinguish them from other involuntarily committed persons (

5).

Adjudication as not guilty by reason of insanity indicates that a determination of not guilty has been made; thus these individuals are considered "nonsentenced offenders" (

6). Whereas patients often initiate the process of help seeking, offenders with mental disorders typically enter treatment for a mental illness through the judicial system. Those who are acquitted as not guilty by reason of insanity can be committed involuntarily to a treatment program due to their mental condition. Often commitment involves at least an initial inpatient forensic evaluation, which could take place in a jail or another correctional facility.

Individuals acquitted as not guilty by reason of insanity who have been committed require court approval for any off-grounds privileges or subsequent release from institutional care to the community (

6). This mechanism, termed "conditional release," is a transitional step toward outright release that enables the court to closely supervise offenders; it provides a means for unilaterally revoking community placements and returning offenders with mental disorders to an institutional setting when evidence of symptomatic relapse or treatment nonadherence exists. The principal goal of conditional release is to minimize potential danger to the community by preventing dangerous behavior (

6). Thus the court has the authority to mandate and judicially supervise continued outpatient treatment of these individuals.

Ultimately, more than 90 percent of all offenders acquitted as not guilty by reason of insanity will be released to the community from the hospital (

3,

5), following the general trend of shifting the site of psychiatric care from traditional institutional settings to nontraditional noninstitutional settings in the community (

7). In the past two decades the risk to public safety posed by insanity acquittees who have demonstrated a potential for violence has spurred the development of specialized outpatient treatment centers, particularly within forensic psychiatry settings (

1).

The essential principles of community-based forensic treatment and treatment outcomes have been summarized elsewhere (

8,

9,

10,

11). Reviewing the outcomes of conditional release, Heilbrun and Griffin (

10) found rearrest rates of 2 to 16 percent for offenders on conditional release, with rates as high as 42 to 56 percent on long-term follow-up after conditional release was terminated. Rehospitalization rates for offenders on conditional release were both higher and more variable, 11 to 78 percent, although most estimates ranged from 11 to 40 percent.

In contrast, studies conducted about two decades ago, one in Connecticut with a seven- to nine-year follow-up (

12) and one in New York with a two-and-a-half- to five-year follow-up (

13), indicated that rearrest rates ranged between 24 and 61 percent for individuals who were acquitted as not guilty by reason of insanity and were released to the community, whereas the psychiatric rehospitalization rates were 18 to 44 percent. Most persons in these earlier studies were discharged unsupervised, with neither monitoring nor treatment after their release from the correctional facility or hospital.

The coercive element of court-mandated treatment has presented only minimal interference with continuing treatment. Patients are informed of possible legal sanctions for noncompliance and agree to adhere to program requirements. Early in treatment, the court order for conditional release ensures that the patient will actually appear at the treatment facility or be cited for being in contempt of court; most patients admit that they would not come for treatment if they were not required to do so.

In this paper, we describe the clinical characteristics at the index hospital admission of our currently active patient group, report prevalence rates of rehospitalization and criminal recidivism in this group, and compare those who were not rehospitalized or rearrested with those who were rehospitalized or rearrested on a variety of possible correlates of relapse and recidivism. Reports published more than a decade ago described outcomes for early program participants (

1,

14,

15,

16). This paper focuses on more recent criminal and psychiatric outcomes—those from 1996—including levels of symptom remission and psychosocial functioning.

Methods

Subjects

We examined the records of the 43 patients treated during 1996 in our outpatient treatment program for offenders with mental disorders who are acquitted as not guilty by reason of insanity. To be included in the program, individuals must have a major mental disorder (symptomatic or in remission) that is likely to benefit from the treatment offered by the program. They must have community supports, such as family and friends, supervised residences, workshops, and social service agencies, and they must agree to the requirements of the program, including demonstrating a full understanding of possible legal sanctions for noncompliance (

8,

14).

Inpatients who are psychiatrically stable and eligible for off-grounds passes may be transported to participate in the outpatient program while continuing as inpatients within the state mental health system. This initial transitional period serves as a bridge to promote continuity between inpatient and outpatient treatment. After discharge from the state psychiatric facility, they continue in the outpatient program.

Exclusion criteria include continued need for intensive inpatient care and a primary diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder or a drug abuse disorder (

8,

14). Approximately 30 percent of those referred as not guilty by reason of insanity are excluded during the assessment process because they are considered unacceptably high risks for criminal recidivism due to the need for continued hospitalization, inadequate environmental support, or a nonviable living situation (

15).

Procedure and data analysis

At the end of 1996 we conducted a retrospective chart review of our clinic records on the 43 patients treated that year. Selection of sociodemographic, psychosocial, psychiatric, criminal, and other outcome variables was guided by "cue domains" identified by Steadman and colleagues (

17). Data were abstracted from the acquittees' charts, coded, and entered into a database.

Data analyses were conducted as follows. First, we tabulated the characteristics of our group before they committed the offense that led to adjudication as not guilty by reason of insanity. Second, we ascertained the prevalence of psychiatric relapse and criminal recidivism after the participants were determined not guilty by reason of insanity. Psychiatric relapse was defined as rehospitalization. Criminal recidivism was defined as rearrest or the commission of a new crime without being arrested. These outcome events were not limited to 1996, but covered all the years since the individual had committed the index offense, even before entry into the program.

Third, we created three subgroups. In the first group were 15 patients who had no rearrests, who had not committed a new crime, and who had not been rehospitalized since their index offense. In the second group were 20 patients who were rehospitalized; the number of rehospitalizations ranged between one and six. In the third group were eight individuals who were rearrested or who committed a new crime.

The second and third groups were not mutually exclusive. Of the eight patients in the third group, five who were rearrested also were rehospitalized, two committed a new crime and were rearrested during their index hospitalization, and rehospitalization information was missing for one patient. Five patients could not be categorized into any of the three outcome groups: four committed no new crimes but remained in their index hospitalization while attending the center's outpatient program, and both rehospitalization and recidivism data were missing for one patient. These five patients did not differ significantly from the other 38 patients in age, age at index crime, and length of time in the program.

We then conducted separate pairwise comparisons between the group with no hospitalizations and no recidivism and the other two groups, because the rehospitalized and recidivistic outcome groups were not mutually exclusive. We compared the groups on a wide range of preoffense baseline measures and on symptomatic and functional improvements. Because we did not have data from a standard symptom rating scale, measurements of improvements were determined by reviewing the available records containing clinicians' impressions and establishing a rating of psychosocial functioning outcomes; they included community living arrangements and social and occupational status, according to realms described by Strauss and Carpenter (

18) and by Tsuang and associates (

19). Depending on the year of assessment, psychiatric diagnoses followed either

DSM-III-R (

20) or

DSM-IV (

21).

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. We used chi square tests for categorical measures and t tests for continuous measures. Mann-Whitney tests were used instead of t tests for skewed and nonnormally distributed continuous measures. Alpha was set at .05 (two tailed) as the criterion level for statistical significance. Complete records were not available for all 43 patients.

Results

Subjects' characteristics

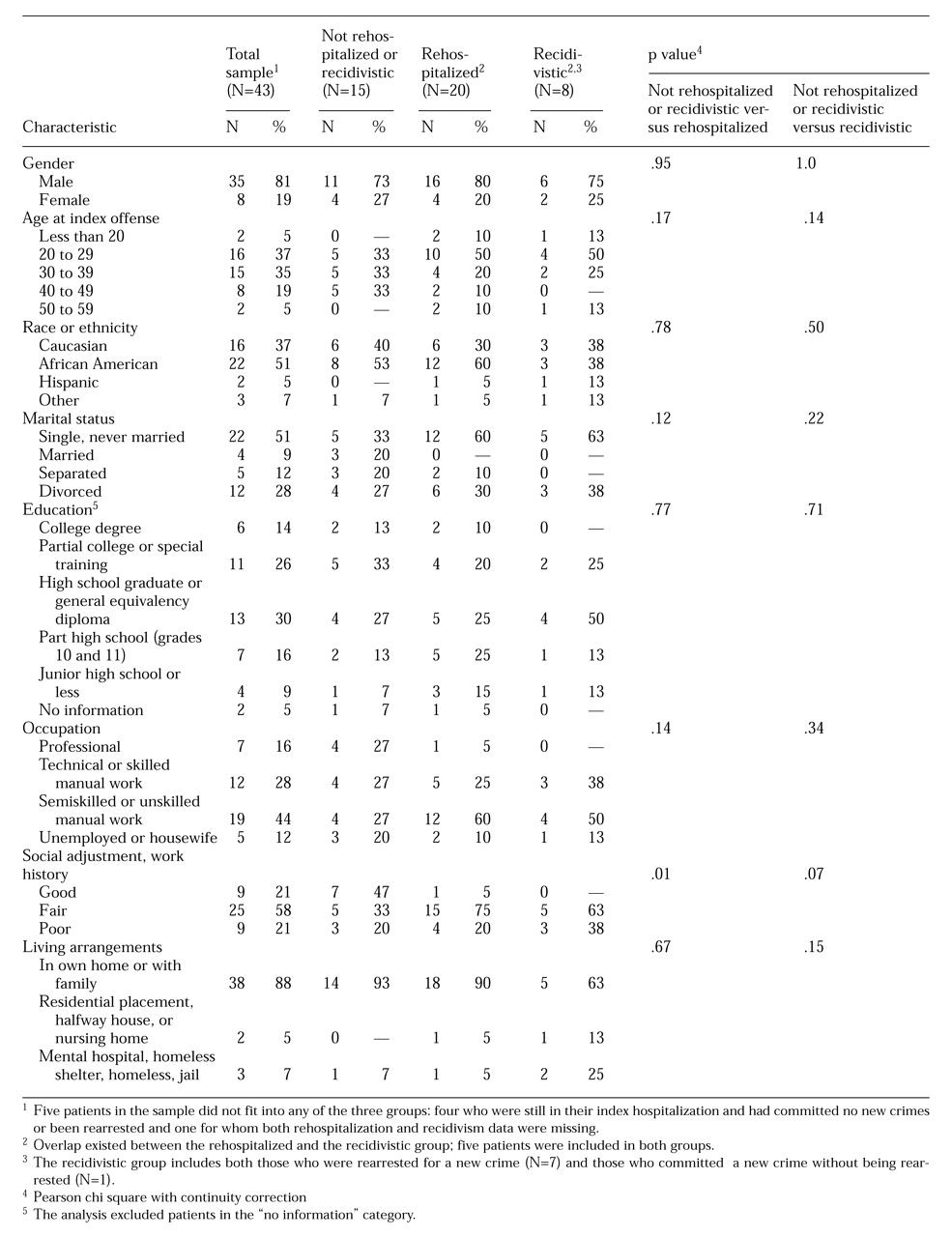

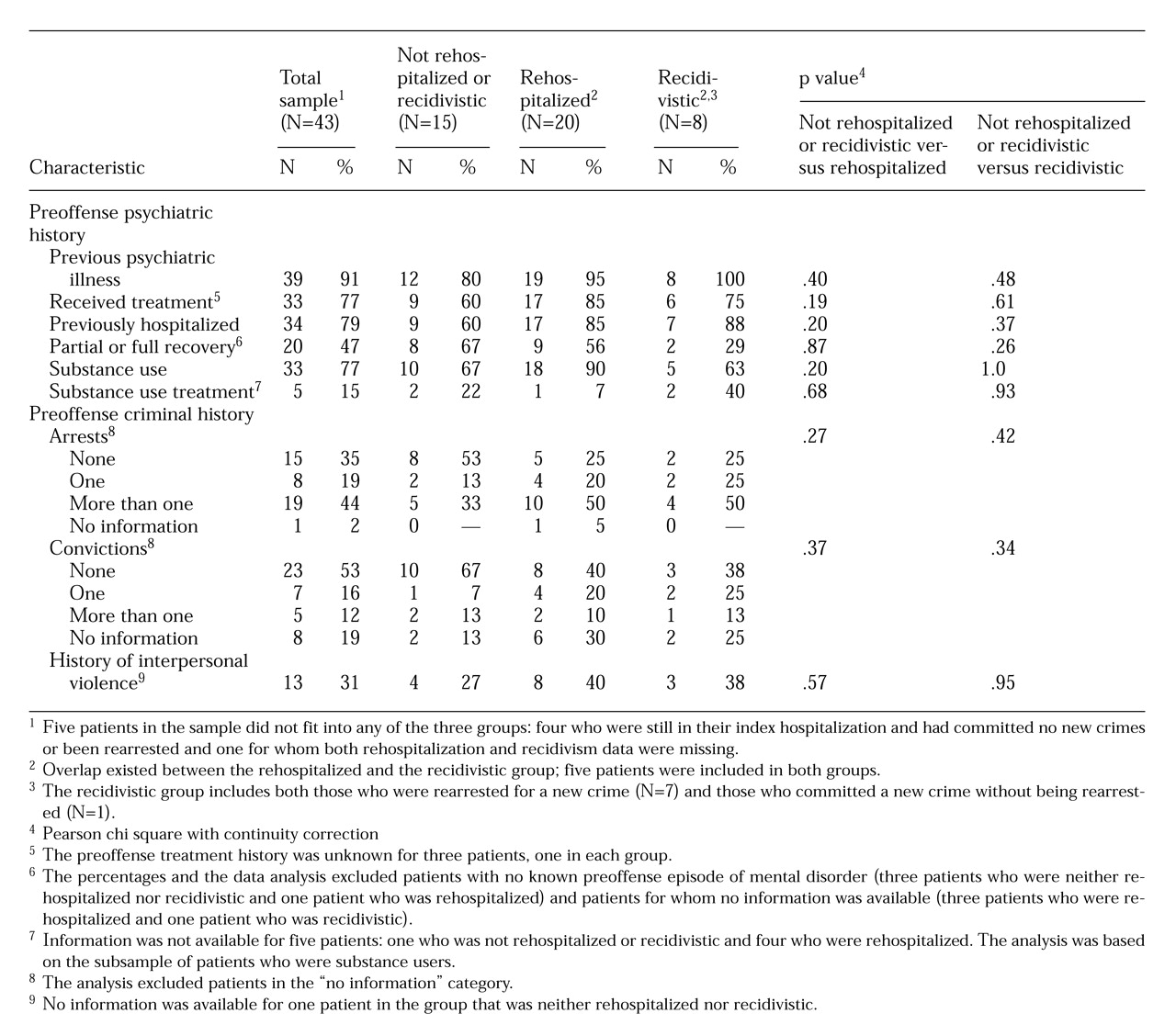

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide information about sociodemographic, psychiatric, and criminal features of the sample before they committed their index offense. The mean±SD age of the group was 45.4±8.8 years, with a range from 26 to 63 years. For all but one of these 43 acquittees, the index event was a major violent offense; 30 acquittees (70 percent) had committed murder. The mean± SD age when the index offense was committed was 32.7±9.4 years, an average of 12.8±4.8 years before the chart review for the study was conducted.

The mean length of participation in the program was 68.4±50.3 months; however, the length of time in treatment for psychiatric illness varied widely—from 4.9 months to 18.4 years. One patient withdrew from the program in mid-1996, after the conditional release period ended.

Rehospitalizations and rearrests

Hospitalization.

During 1996 seven of the 43 acquittees (16 percent) remained hospitalized continuously since being adjudicated as not guilty by reason of insanity; for these individuals adjudication had occurred between 6.7 years and 13.4 years ago. They obtained off-grounds passes to attend our outpatient program.

Of the 36 acquittees who were released from their index hospitalization, 20 (56 percent) were rehospitalized at least once since program entry. Eleven were rehospitalized once, six twice, one three times, and two six times. In 1996 eight were rehospitalized, and 18 spent at least part of 1996 in the hospital; for ten patients the 1996 hospitalization was a continuation of their 1995 admission.

Of the 39 patients for whom hospitalization data were available, 21 (54 percent) were not hospitalized in 1996. (Information about rehospitalization was missing for four persons.) Thirty-two patients (82 percent) spent at least part of the year out of the hospital.

Recidivism.

Since their index offense, seven of the 43 patients (16 percent) were rearrested for a new crime, including three in 1996; one patient committed a new crime while still hospitalized but was not rearrested. Five of those who were rearrested also were rehospitalized, and one assaulted another patient and was rearrested while hospitalized. One patient was arrested three times, including twice in 1996, but information about rehospitalization for this patient could not be found in the records. For five of the eight patients who were rearrested, the crime involved violence toward another person. The types of new crimes committed by the other three patients were violence to property, a drug-related offense, and a nonviolent non-drug-related offense.

Intergroup comparisons

Personal background.

As

Table 1 and

Table 2 show, little variation was found between the groups. On sociodemographic characteristics, neither the rehospitalized group nor the criminally recidivistic group differed significantly from those who were neither rehospitalized nor recidivistic, with one exception. Social adjustment was significantly worse among the rehospitalized patients and marginally worse among recidivistic patients.

The rehospitalized and recidivistic groups did not differ significantly from the group that was not rehospitalized or recidivistic in age, age at index crime, years since index crime, and number of years in the program.

Psychiatric and criminal histories.

A smaller percentage of the patients who were neither rehospitalized nor recidivistic had a previous psychiatric illness, and a larger percentage of these patients had at least partial recovery. A larger percentage of the rehospitalized patients reported substance use but a smaller percentage had been in treatment for substance use. A smaller percentage of patients who were not hospitalized or recidivistic had a history of interpersonal violence, arrests, or criminal convictions. However, none of these differences approached statistical significance.

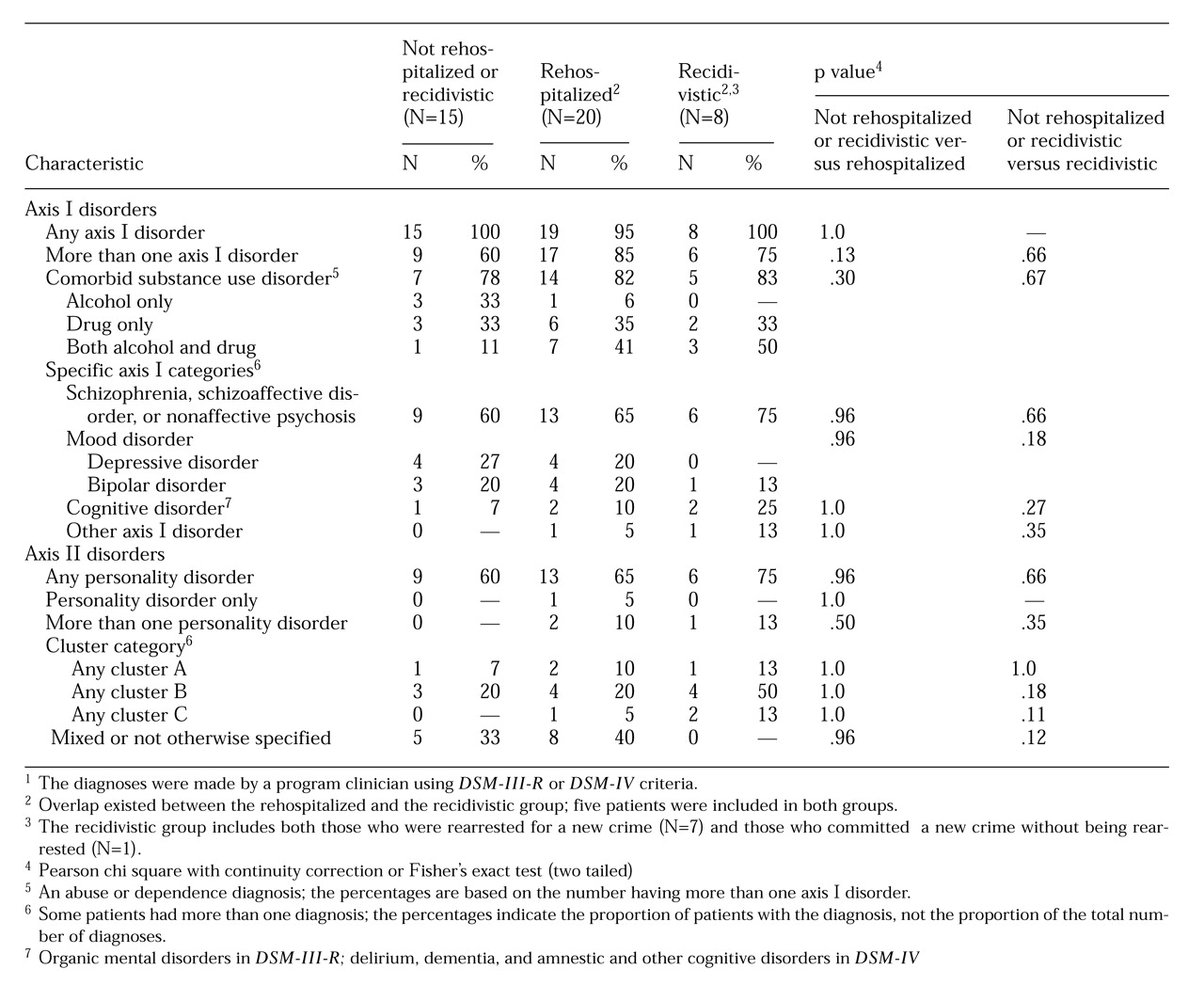

Psychiatric diagnoses.

Table 3 shows the breakdown by group for axis I and II psychiatric diagnoses, which were based on comprehensive evaluations conducted by the program staff.

Axis I disorders were diagnosed for all but one patient. The most prevalent non-substance-related catagory was schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or a nonaffective psychosis; 25 of the 38 patients who could be categorized as rehospitalized or recidivistic (66 percent) had one of these disorders. More than 70 percent, or 27 of the 38 patients, had more than one axis I diagnosis. A substance use disorder was the most frequent comorbid condition for 22 patients. Altogether, 58 percent, or 22 of the 38 patients, had a comorbid substance-related disorder. Every patient who had a substance-related disorder had at least one other axis I diagnosis. The groups did not differ significantly in diagnostic composition.

Axis II personality disorders were diagnosed for 24 of the 38 patients who could be categorized as rehospitalized or recidivistic (63 percent). One patient had a personality disorder and mild mental retardation, but no axis I diagnosis. Personality disorder not otherwise specified and mixed personality disorder were the most frequently made axis II diagnoses. For those that could be more precisely classified, cluster B diagnoses, particularly antisocial and borderline personality disorders, were made more frequently than cluster A or C diagnoses. The groups did not differ significantly in axis II disorders.

Treatment and outcomes

Treatment.

During 1996 a total of 27 percent of the patients in the group that was neither rehospitalized nor recidivistic were scheduled to attend the program at least every other week, compared with 65 percent of patients in the rehospitalized group (χ2=8.22, df=2, p=.02) and 50 percent of patients in the recidivistic group (not a significant difference). Twenty-seven percent of the patients who were neither rehospitalized nor recidivistic attended less than once a month, and 47 percent attended one or two times a month. The proportions were smaller in the other two groups. For the rehospitalized group these figures were 0 and 35 percent, respectively, and for the recidivistic group, they were 13 and 38 percent, respectively.

Sixty-seven percent of the group not rehospitalized or recidivistic received psychotropic medications, compared with 90 percent of the rehospitalized group and 75 percent of the recidivistic group. These differences were not statistically significant. All patients were involved in psychotherapy as a program requirement.

Compliance.

Compliance with appointment sessions was defined as attending more than 70 percent of scheduled sessions. For medication regimens, compliance was defined as taking more than 70 percent of scheduled doses, which was assessed by self-report. Both types of compliance were higher among the patients not rehospitalized or recidivistic. Their compliance rates were 87 percent for sessions and 80 percent for medications. For the rehospitalized patients, rates of 75 percent and 69 percent, respectively, were found; medication compliance data were missing for three patients in this group. For recidivistic patients, compliance rates were 50 percent for sessions, with missing data for one patient, and 40 percent for medications, with missing data for two patients. No statistically significant association was found between rehospitalization or rearrest and either type of compliance.

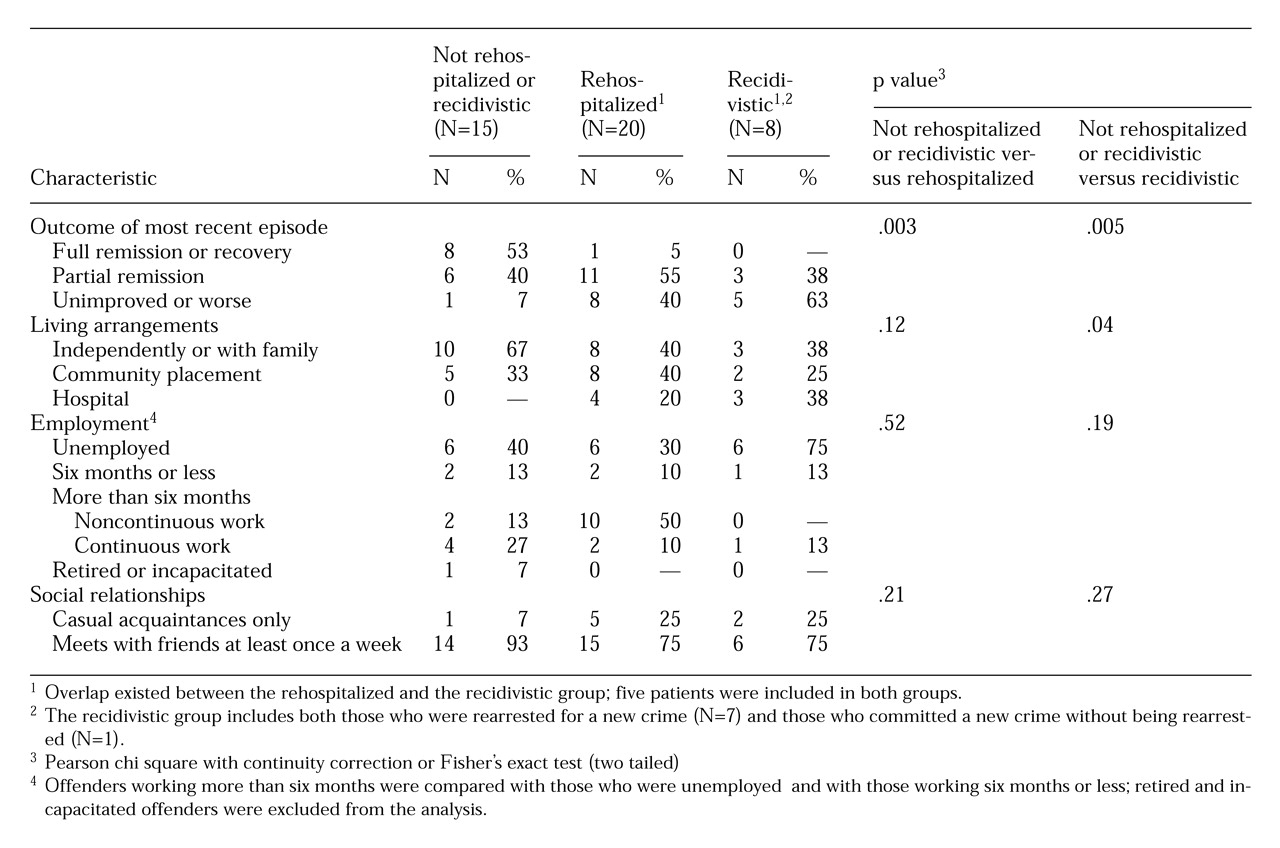

Symptoms and insight.

Table 4 shows the rates of symptom remission and psychosocial recovery for acquittees in each of the three groups. Rehospitalization and rearrest were associated with significantly lower rates of full symptom remission and higher rates of unimproved or worse symptoms. No patient was reported to be suicidal or homicidal.

Full insight into their illness was considered present in eight (53 percent) of the patients who were not rehospitalized or recidivistic; however, it was present in only eight (40 percent) of the rehospitalized patients and two (25 percent) of the recidivistic patients. These differences were not statistically significant.

Substance use.

Information about drug and alcohol use was obtained by self-report; urine screens were done only infrequently. In 1996 the rate of alcohol use was higher among patients in the rehospitalized group (30 percent) but not among those in the recidivistic group (13 percent), compared with the group with no rehospitalizations or rearrests (13 percent). In 1996 rates of illegal drug use were higher in the rehospitalized group (10 percent) and the recidivistic group (13 percent) than in the group with no rehospitalizations or recidivism; no patient in the latter group reported illegal drug use. Pairwise comparisons showed no significant association between rehospitalization or recidivism and substance use.

Social and functional outcomes. Table 4 also shows patients' level of recovery in terms of psychosocial functioning, which was measured by three indicators—living arrangement, employment, and social relationships. Patients who were neither recidivistic nor rehospitalized had a better outcome in terms of independent living in the community, which was statistically significant only in comparison with those who were recidivistic. Both the patients who were rehospitalized and those who were recidivistic had higher rates of underemployment or unemployment than those who remained out of jail and the hospital, but these associations were not statistically significant. The level of social relationships was similar in the three groups.

Altogether, 26 of the 38 patients (68 percent) had at least one of the three indicators of difficulty reintegrating into the community, including nine (60 percent) of the patients who were not rehospitalized or rearrested, 14 (70 percent) of the rehospitalized patients, and seven (88 percent) of the recidivistic patients.

Clinician-rated Global Assessment of Functioning scores were available for only 19 patients—seven patients who were not rehospitalized or rearrested, ten patients in the rehospitalized group, and two patients in the recidivistic group. The mean scores were similar for the three groups, ranging from 70.4 to 72.5.

Discussion

We have presented clinical data from an outpatient court-mandated psychiatric treatment program for offenders with mental disorders adjudicated as not guilty by reason of insanity. We examined associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and program outcomes of those who were neither rehospitalized nor recidivistic, those who were rehospitalized, and those who were rearrested or who committed a new crime without being arrested. Although data about sociodemographic characteristics, past behavior, and diagnosis may provide a framework for characterizing this population and useful clues, or "cue domains" (

17), for assessing risk factors for recidivism and rehospitalization, these pieces of information may be insufficient for predicting the occurrence of specific events such as violent behavior (

17,

22,

23).

Previous evaluative studies have examined rearrest and rehospitalization as outcome measures of treatment success (

9,

10). One may argue that these data merely indicate that persons with mental illness are hospitalized frequently and are more frequently rearrested than persons without mental illness and that rehospitalization and rearrest rates in this specialized treatment population cannot be easily compared, particularly without an external control group.

On the other hand, both outcomes are a function of the duration of follow-up—with longer observation periods, the rates of rearrest and rehospitalization increase. Solomon and associates (

24) have commented that persons under intensive supervision may be more likely to return to jail because they have a higher probability of being observed in violation of probation or parole conditions. They suggest that for decompensating severely mentally ill persons who have minimal access to traditional community services, mental health professionals may view jail incarceration as a therapeutic intervention because of the access to mental health treatment in jail (

25).

Similarly, judicious use of hospitalization may be associated with lower rearrest rates (

9). Rather than using rehospitalization only as an outcome measure to indicate treatment failure, it should also be recognized as part of the treatment process to prevent criminal recidivism (

9). Timely hospitalization may short-circuit incipient aggressive behavior associated with psychopathology. Thus hospitalization may be an important intervention to try to prevent criminal recidivism in this chronically mentally ill group (

1,

14,

16). Although it is true that hospitalization is a type of confinement, it is less restrictive than incarceration, and its purpose is to treat the behavior, not to punish it.

Monitoring treatment compliance is an important risk assessment tool for offenders with mental disorders who are adjudicated as not guilty by reason of insanity. However, our data suggest that mandated treatment is no guarantee against noncompliance and continued substance use, even if these factors are grounds for the revocation of conditional release. These two behaviors put offenders and nonoffenders alike at higher risk of relapse (

26,

27), and the potential consequences for offenders are more serious.

Substance abuse has been detected increasingly among persons with serious mental disorders and heightens the risk of psychosis and violent and assaultive behavior (

28,

29). As many as half of all patients with schizophrenia abuse alcohol or other drugs during their lifetime. In a study that controlled for treatment noncompliance among patients with schizophrenia by giving them long-acting decanoate neuroleptic injections (fluphenazine or haloperidol), Gupta and colleagues (

30) observed that those with comorbid substance abuse averaged five times more hospital admissions over a two-year interval. The largest diagnostic group in our study consisted of individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or nonaffective psychoses; 12 of the 25 patients in this group had lifetime comorbid substance use disorders. Thus the potential for substance use and abuse should be addressed as part of comprehensive treatment planning and risk assessment.

A few general concerns arise about the meaning of our data. Predictions of criminal recidivism or other behaviors based on these data must consider potential sources of bias. A potential for selection bias exists because the mentally disordered offenders program treats a relatively small and select sample. The representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings must be considered (

8). More than a decade ago we reported that more than 80 percent of our patients were diagnosed as having schizophrenia or an affective disorder and that almost 70 percent had been charged with murder or attempted murder (

1,

14,

15,

16). Ninety-five percent of more recent participants had one of these diagnoses, and 70 percent were charged with murder.

The data reported here were derived largely from personal experiences and observations, both individual and programmatic. The charts we reviewed contain subjective impressions recorded by clinicians. None of the data we used were collected with standard symptom rating scales or global assessment instruments administered by trained clinical raters who demonstrated interrater reliability and were blind to the study protocol and subject status. Furthermore, without a control group, it is hard to say what specific impact the program may have on this population.

Conclusions

More effective methods for managing this complex clinical forensic population and for improving outcomes are needed. Important work remains to clarify the characteristics of offenders that are amenable to rehabilitative efforts and to develop programs that can treat these individuals cost-effectively. Challenging clinical questions must be addressed. For example, what is an acceptable level of recidivism? Predicting behaviors with low rates of occurrence in the general population, such as criminal behaviors and violence, remains problematic, and thus determining who requires more intensive treatment and monitoring can be fraught with peril. We need guidelines for assessing and managing risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Roderic Barnes for conducting the chart reviews and data abstraction and Thomas Haywood for data coordination.