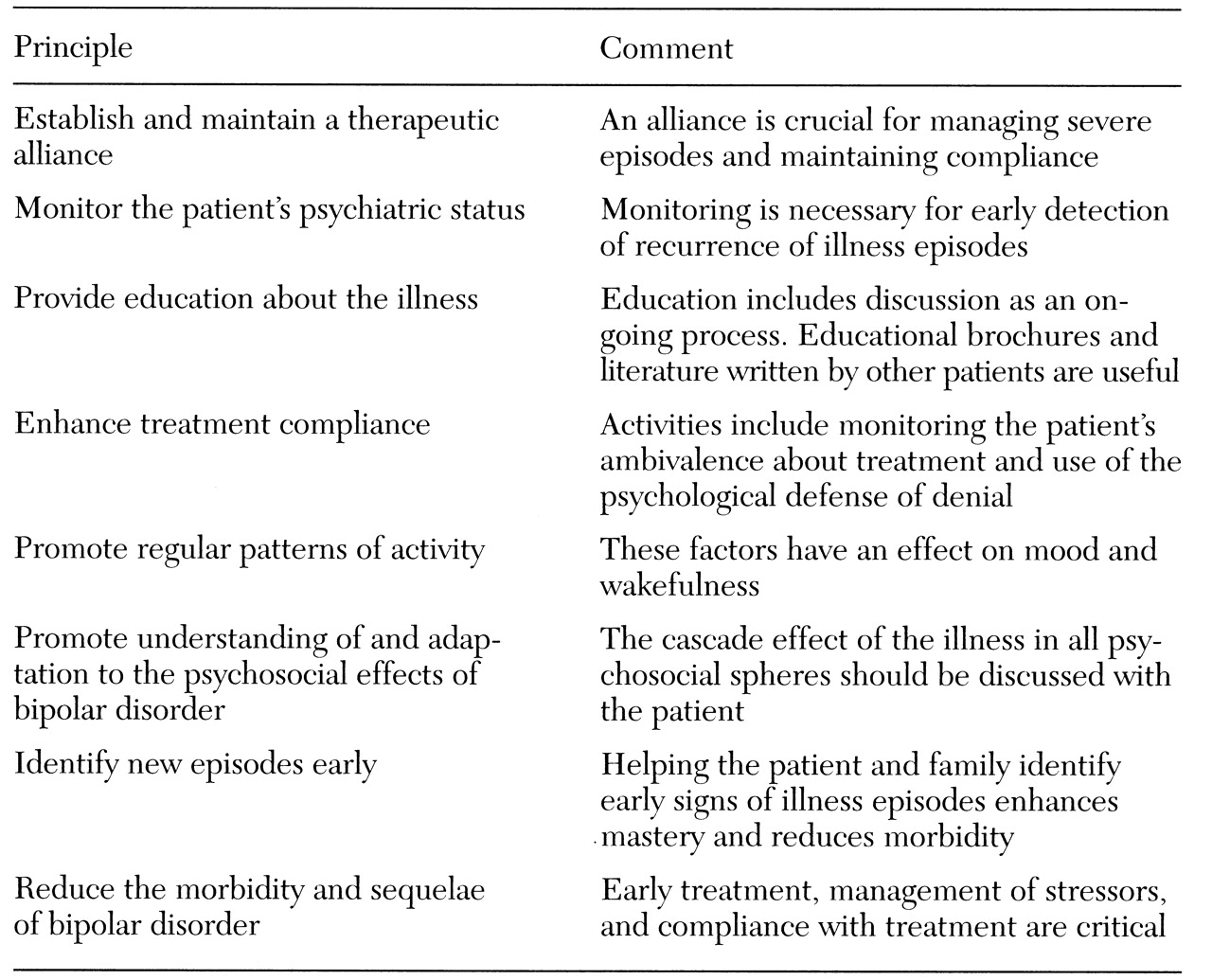

Fortunately, many advances in the understanding of bipolar disorder have occurred over the past ten years. First, pharmacologic options now include lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine as standard treatments, and electroconvulsive therapy, clozapine, and antipsychotic medication as alternative or adjunctive therapies. Second, the importance of psychosocial issues for understanding patients' illnesses and factors affecting treatment compliance is more fully realized. Although the study of psychoeducation, self-help, and psychotherapeutic interventions for individuals, couples, and families is only beginning, these modalities are frequently utilized. Indeed, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) practice guideline for bipolar disorder states that "specific psychotherapeutic treatments may be critical components of the treatment plan" (

5).

This paper reviews the epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis and assessment, and management of bipolar disorder.

Epidemiology

Over the course of a lifetime, bipolar I disorder affects approximately .8 percent of the adult population, and bipolar II disorder affects approximately .5 percent (

7). Males and females are equally affected by bipolar I disorder, whereas bipolar II disorder is more common among women. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study reported a mean age of onset of 21 years for both types of bipolar disorder (

8). When age of onset is stratified in five-year intervals, the peak age of onset is the 15-to-19-year age group, followed by the 20-to-24-year age group. In a survey of members of the NDMDA, more than half of the patients did not seek care for five years after first experiencing symptoms, and 36 percent did not seek care for more than ten years (

9). According to the survey, the correct diagnosis was not made until an average of eight years after respondents first sought treatment.

In 1990 the economic burden of bipolar disorder in the U.S. was estimated to be $15.5 billion in diminished or lost productivity in work performance alone (

10). In 1990 patients in treatment lost an estimated 152 million cumulative days from work, and untreated patients lost another 137 million days. Undertreatment of bipolar and depressive disorders is a significant factor in weighing the disorders' potential costs, because it is assumed that one-third of the untreated population with bipolar disorder can eventually be treated successfully (

11).

Theoretically, efficient treatment of bipolar disorder would cost $25.6 billion annually and save $10.5 billion, a net loss of $15.1 billion, in the first year. However, by the end of the second year of treatment, the savings of $12.6 billion would exceed costs of $7 billion, for a net gain of $5.6 billion (

11). Because bipolar disorder is a long-term or lifetime disorder, economic analyses need to examine a longer period of time when calculating costs or benefits.

Etiology and pathophysiology

Researchers have not developed a single hypothesis that unifies genetic, biochemical, pharmacological, anatomical, and sleep data on bipolar disorder (

12). Epidemiological evidence, particularly studies of concordance in identical and fraternal twins, has implied that affective disorders are heritable. For family members of probands with bipolar disorder, the risk of morbidity is between 2.9 and 14.5 percent for bipolar disorder and between 4.2 and 24.3 percent for unipolar depression, depending on the diagnostic criteria used and the heterogeneity of the probands (

12).

Whether bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, hypomania, cyclothymia, and unipolar depression are genetically related or distinct entities is unknown (

13). It remains unclear if the phenotype of mood disturbance is the best indicator of a genetic etiology. Therefore, it has been difficult to construct models for linkage analysis, which are necessary when simple Mendelian models do not explain inheritance—that is, when several independent genetic mutations contribute independently. However, no linkage is unequivocally established in bipolar illness at this time.

It is crucial to screen the entire genome for linkage to bipolar illness in populations, derive data from affected rather than unaffected individuals in screening studies, develop hypotheses from preliminary findings, and conduct further investigations (

13). For the clinician, the concerns of patients and their relatives can be dealt with through counseling that draws on empirical risk figures in the majority of cases and on linkage results for large pedigrees that have been investigated thoroughly.

Biochemical and pharmacologic studies led to hypotheses involving the neurotransmitters catecholamine and serotonin to explain bipolar disorder. The catecholamine hypothesis presumes that mania is due to an excess of catecholamines, and depression to their depletion. Norepinephrine has been implicated mainly because of the link between depression and aberrant noradrenergic transmission. Dopamine has been implicated because the dopamine precursor L-dopa almost uniformly produces hypomania among patients with bipolar disorder. Amphetamines can also produce hypomania among patients with bipolar disorder, as well as those without it. Antipsychotic medications that selectively block dopamine receptors, such as pimozide, are effective for severe mania. Chronic use of tricyclic antidepressants presumably leads to activation of central dopaminergic neurotransmission.

The "permissive hypothesis" of serotonin function holds that low serotonergic function accounts for both manic and depressive states through defective dampening of other neurotransmitters, mainly norepinephrine and dopamine. Many other etiological theories involving neurochemicals such as neurotransmitters, enzymes, and neuropeptides are under investigation, as are theories involving the endocrine and immunological systems.

A wide range of neuroanatomical and neuroimaging studies are being conducted to learn more about bipolar disorder (

12). The study of neuroanatomy is important because organic lesions are associated with signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder and because mood stabilizers are able to stabilize symptoms without altering the underlying neuropathological deficit. Lesions in the frontal and temporal lobes are most frequently associated with bipolar disorder. Left-sided lesions tend to be associated with depression and right-sided lesions with mania, though differences may occur in the posterior regions of the brain. For example, depression may be associated with lesions in the right parietooccipital region.

No abnormalities have been consistently found through computer tomography studies, although ventricular enlargement has been noted in some studies. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have revealed an increase in white matter intensities associated with bipolar disorder and correlated with age (

14), although the clinical significance of these findings is unknown. Overall, most functional imaging studies, including single photon emission computer tomography and positron emission tomography, have noted prefrontal and anterior paralimbic hypoactivity in bipolar depression; preliminary studies of manic patients have yielded inconsistent findings.

Two other important biochemical models for bipolar disorder have been suggested. Post and collaborators (

15) have proposed that electrophysiological kindling and behavioral sensitization underlie bipolar disorder, particularly the increasing frequency of episodes over time. Parallels between this model and bipolar disorder include the predisposing effects of both genetic factors and early environmental stress; the presence of threshold effects, in which mild alterations eventually produce full-blown episodes; the pattern that early episodes require precipitants while later ones do not; and the sequence of repeated episodes of one phase—mania or depression—leading to the emergence of the other (

12).

Desynchronization of circadian rhythm has also been implicated in bipolar disorder. Data from animal studies indicate that periodic physiological disturbances can occur if two rhythms become desynchronized—that is, if one becomes free-running in and out of phase with the other (

12). It is unclear if, and how, genetics contribute to the role of circadian and seasonal rhythms, the capacity for kindling and sensitization, and variation in the course of bipolar disorder, such as rapid cycling.

Diagnosis

The fourth edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (

DSM-IV) includes bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (

16). The episodes are characterized by mania, hypomania, depressive symptoms, and mixed symptoms.

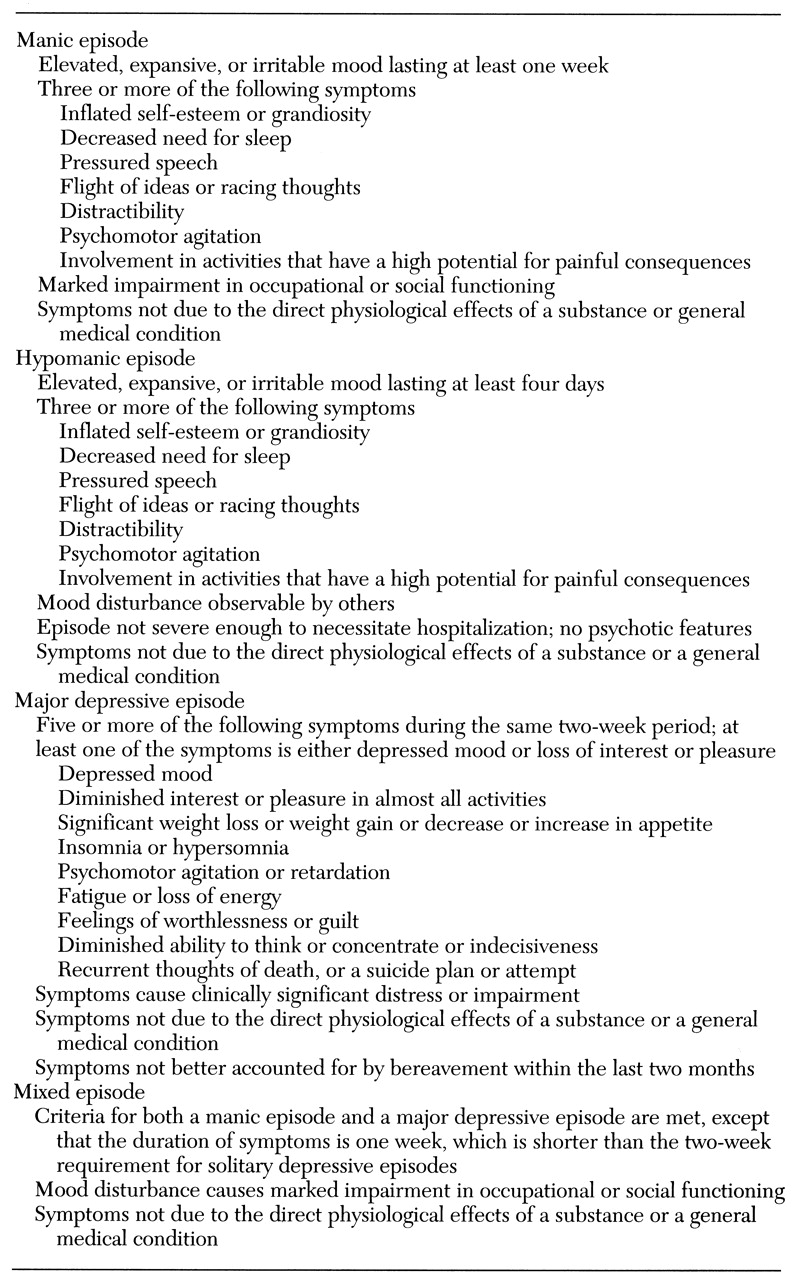

The diagnostic criteria for the four types of episodes are shown in

Table 1. By definition, patients with bipolar I disorder have had at least one episode of mania, whereas those with bipolar II disorder have had major depressive and hypomanic episodes. Mania occurring in patients who are taking medications such as corticosteroids or antidepressants or who have a medical illness is known as secondary mania and is classified separately in

DSM-IV as substance-induced mania or mania due to a general medical condition.

The differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder is quite extensive and complex. First, the presentation of patients with bipolar disorder can be similar to that of patients with other mood and psychotic disorders, including major depression, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. A positive family history of mood disorder is suggestive of a mood disorder, even when the patient presents with prominent psychotic symptoms. Second, bipolar disorder can be associated with substance-induced disorders and with recklessness, impulsivity, truancy, and other antisocial behavior. Therefore, the disorder must be differentiated from substance-related disorders, antisocial personality disorder, and other personality disorders. Among children and adolescents, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder must be considered. Third, the relationship between affective illness and personality must be considered in making the diagnosis of bipolar disorder (

17).

Bipolar disorder should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with unipolar depression. Of 559 patients in the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study, 3.9 percent were eventually given a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and 8.6 percent a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder on follow-up over two to 11 years (

18). Prospective predictors of bipolar I disorder were acute onset of depression, severity of the depressive episode, and psychosis, while predictors of bipolar II disorder included earlier age of onset, higher rates of substance abuse, disruption of psychosocial functioning, and a protracted course. These findings are consistent with the findings of a study in which patients with bipolar disorder had an earlier and more acute onset, more total episodes, more familial mania, and equal sex distribution, compared with patients with unipolar depression (

19).

Assessment

The evaluation of a patient with bipolar disorder is a complex clinical task. Neuropsychiatric assessment includes a complete history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation. The laboratory evaluation includes a complete blood count, serum chemistries, thyroid function tests, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Electroencephalograms and imaging studies may be reasonable as part of the initial assessment.

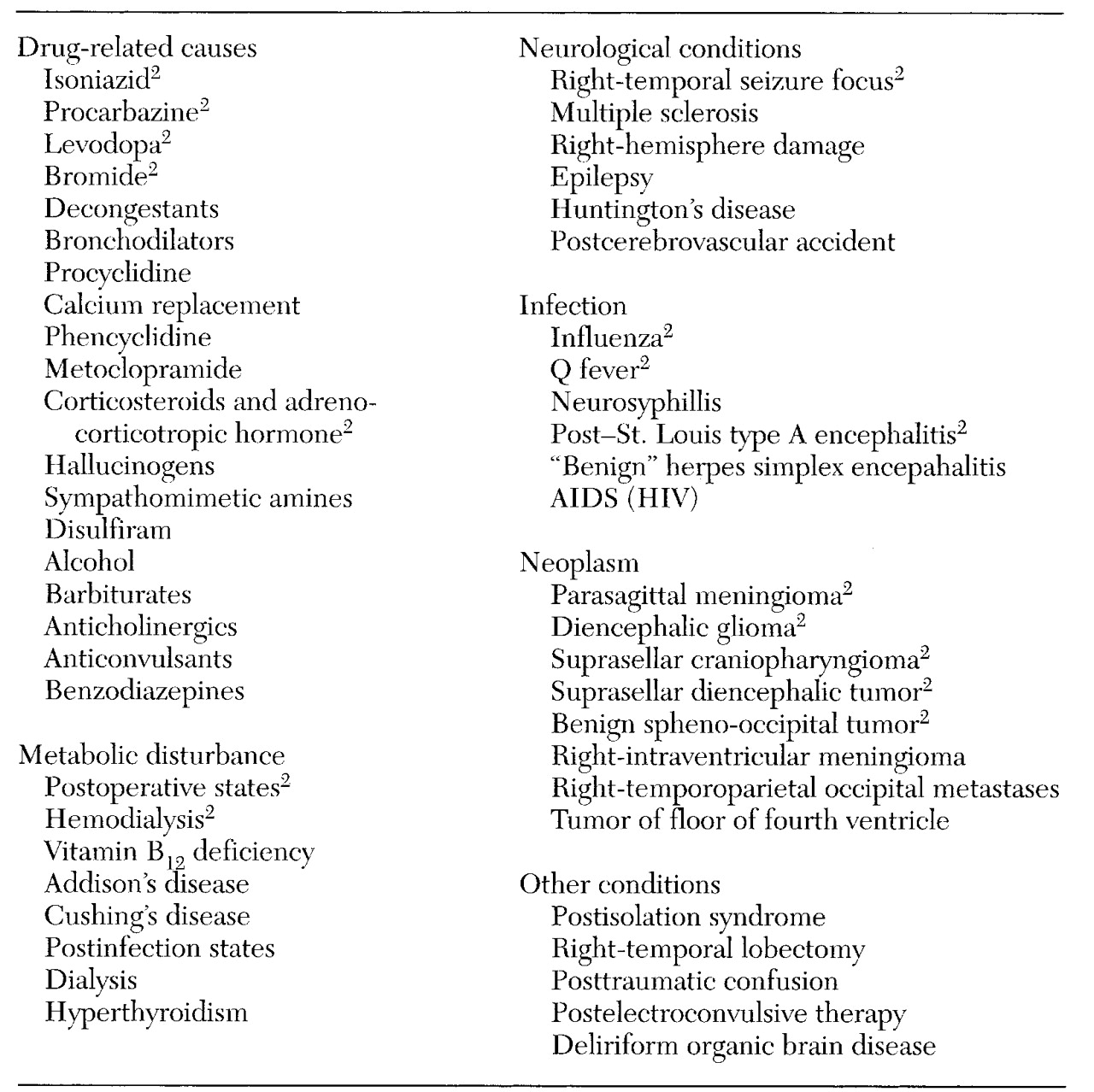

It is particularly important to detect episodes of secondary mania, which has been recognized as a subtype of mania since the 1970s (

12,

20). In

DSM-IV, two types of secondary mania—substance-induced mania or mania due to a general medical condition—are described. Secondary mania is often difficult to treat. Although correction of the underlying organic factor, which could be infectious, toxic, or metabolic, may effectively reverse the manic presentation, many organic factors, such as stroke, trauma, and aging, are not reversible. Patients with mania originating in late life are more likely to have an underlying organic disturbance, negative family history of affective disorder, irritable behavioral characteristics, a tendency toward treatment resistance, and a higher rate of mortality (

12,

20). A list of frequent etiologies of secondary mania is shown in

Table2.

After determining if the patient meets criteria for a specific episode type, the clinician assesses the patient for the presence of psychotic features, cognitive impairment, risk of suicide, risk of violence to persons or property, risk-taking behavior, sexually inappropriate behavior, and substance abuse. In addition, it is important to assess the patient's ability to care for himself or herself, childbearing status or plans, housing, financial resources, and psychosocial supports. The patient's self-report of symptoms may conflict with observation by others. Therefore, accurate assessment depends on information from several sources, including the patient, the patient's significant others, and records of past treatment.

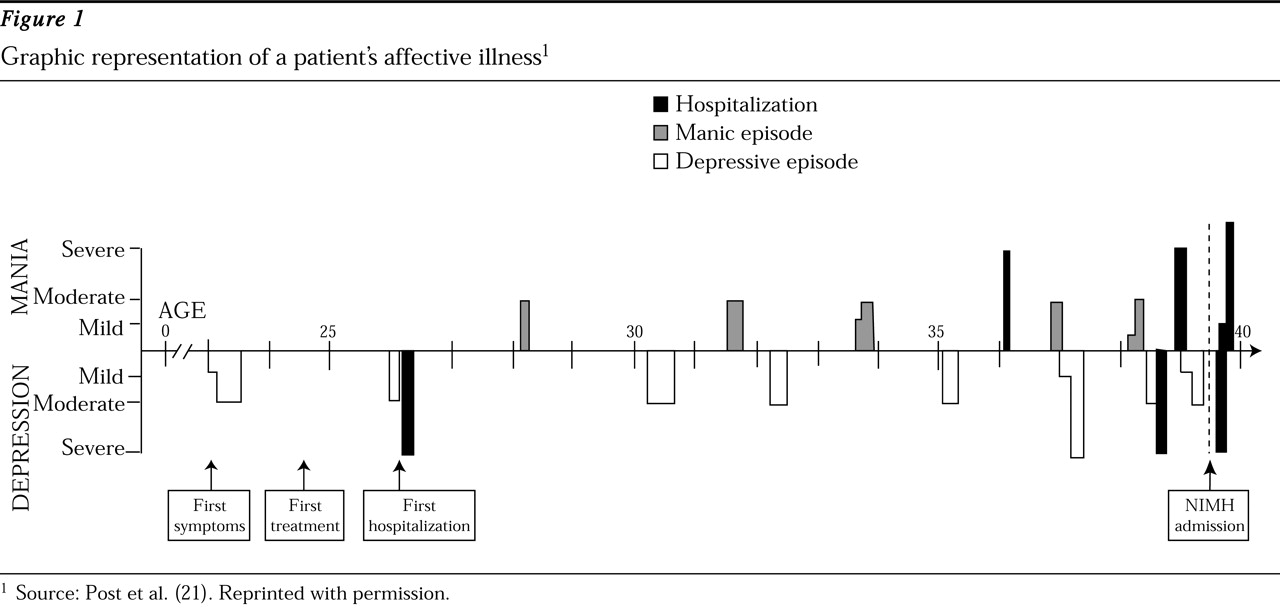

Knowledge of a patient's pattern of illness is perhaps the most useful guide to treatment. Graphic representation of the illness, an example of which is shown in

Figure 1, can be used to consolidate information about the sequence, polarity, severity, and frequency of illness episodes and their relationship to stressors and treatment (

21). Such representations are also useful for patient education and may help in developing a therapeutic alliance (

21).

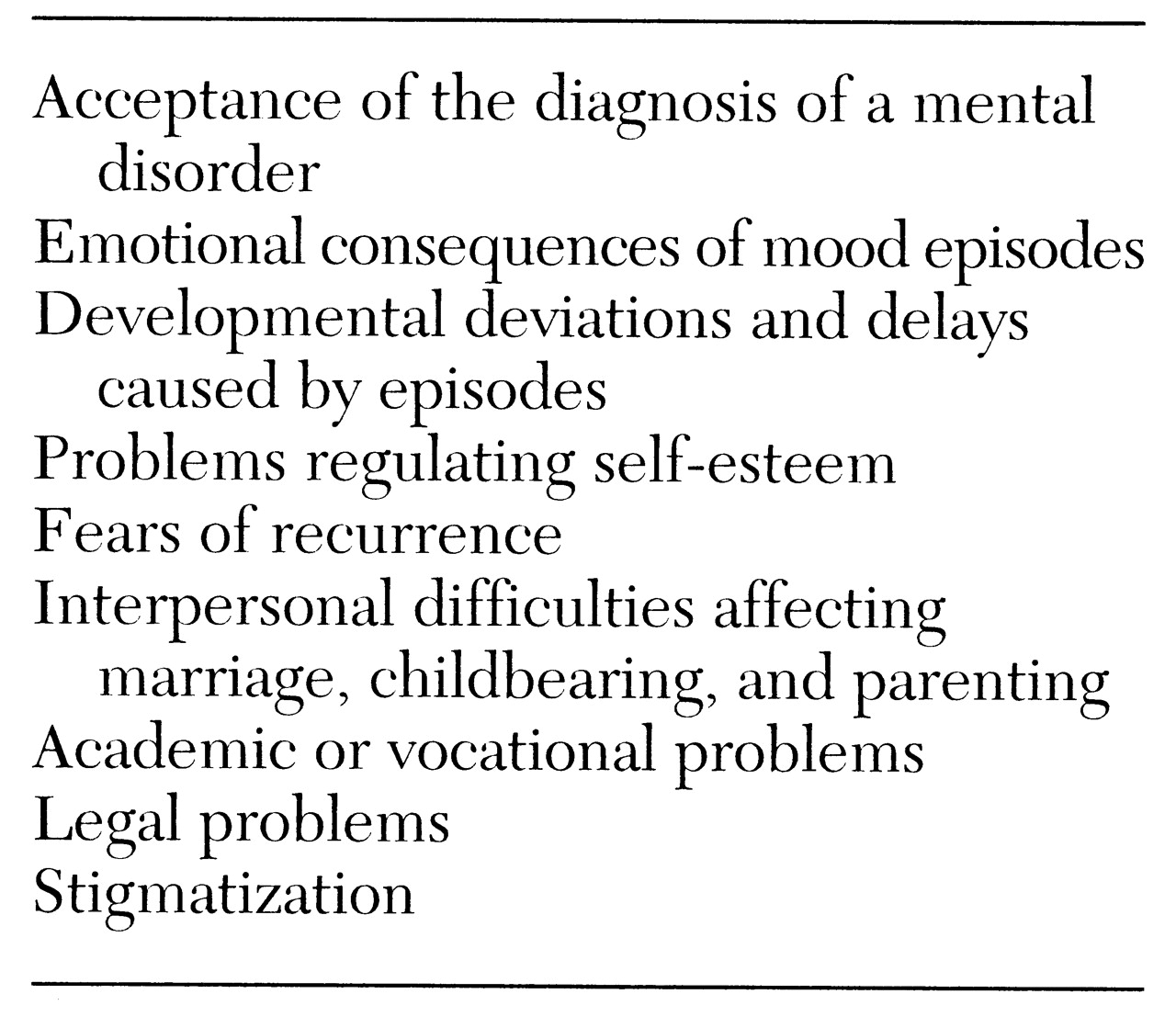

Comorbidity in bipolar disorder

The rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders among individuals with bipolar disorder are important for several reasons. Of primary concern is the association of comorbidity with poorer outcome and poorer treatment response (

69). Accurate diagnosis and aggressive treatment of comorbid disorders may influence treatment decisions and improve treatment response. With the increased attention to cost containment in the current medical practice environment, comorbidity may also directly influence patterns of treatment availability and reimbursement. Again, accurate assessment of comorbid psychiatric disorders is likely to be an important factor in providing the most cost-effective care.

Despite the clear importance of comorbidity in the assessment and treatment of bipolar disorder, this area remains relatively understudied. Epidemiologic data have indicated that several psychiatric disorders co-occur with bipolar disorder at higher rates than would be expected by chance alone. They include substance use disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, panic disorder, and impulse control disorders.

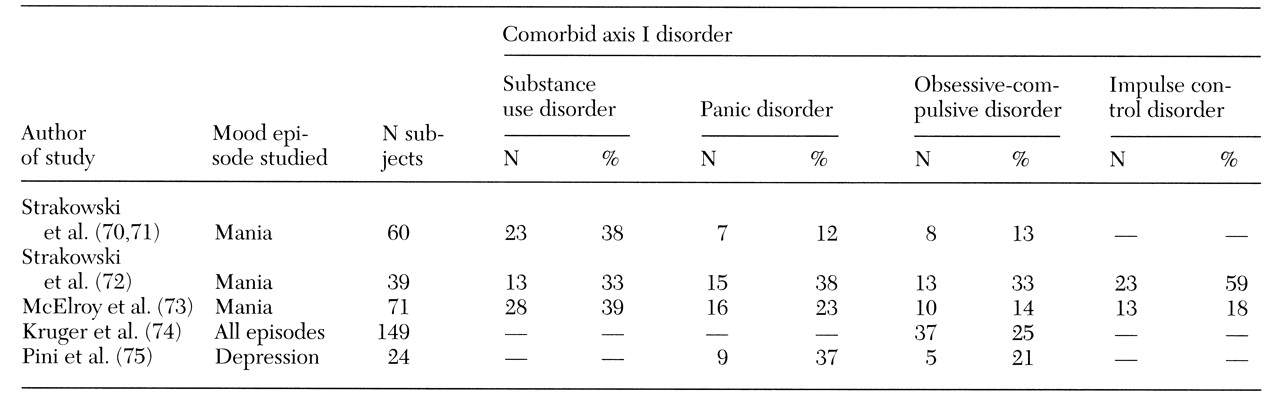

Table 5 summarizes the results of several studies that have noted the high prevalence of comorbid disorders among individuals being treated for bipolar disorder (

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75). Alcohol abuse or dependence was the most common substance use disorder of the patients in these studies. A wide range of other substance abuse and dependence disorders was noted as well. All impulse control disorders can occur with bipolar disorder, with pathological gambling and kleptomania the most common comorbid diagnoses.

Data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study indicated that bipolar disorder was associated with the highest risk (odds ratio of 6.6) of any axis I disorder for coexistence with a drug or alcohol use disorder (

76). More than 60 percent of individuals with bipolar disorder met lifetime criteria for a substance use disorder. The National Co-Morbidity Study (

77), a more recent epidemiologic survey, similarly found bipolar disorder to be commonly associated with substance use disorder (odds ratio of 6.8).

The diagnosis of bipolar disorder when the patient also has a substance use disorder is difficult because the effects of drug abuse, particularly chronic use, can mimic both mania and depression. The clinician should ask very specifically about affective symptoms that predated the onset of substance use and that occur during abstinent periods and should diagnose an affective disorder only if symptoms clearly predated the substance use or persist during periods of abstinence. In the absence of either of these criteria, the clinician must observe the patient prospectively for remission of symptoms during a period of abstinence. For depression, two to four weeks of abstinence may be necessary for accurate diagnosis because symptoms of withdrawal overlap substantially with those of depression. Because mania is likely to be mimicked by substance intoxication but not substance withdrawal, shorter periods of abstinence are necessary for diagnosis of patients with manic symptoms.

Few data about the best treatment for individuals with comorbid substance use and bipolar disorder are available. Some studies have indicated that these patients have a more difficult course of illness and are more treatment resistant (

78,

79). One open-label pilot study has shown promising results with valproate (

80), but this finding has yet to be demonstrated in a controlled clinical trial. In general, adequate pharmacologic control of mood instability is an important component of treatment for these individuals, but this intervention alone is not sufficient. Involvement of the patient in psychosocial rehabilitation, specifically cognitive-behavioral, family, and 12-step groups for substance abuse, is essential. Residential or intensive outpatient programs may also be helpful. The use of pharmacologic adjuncts to promote abstinence, such as naltrexone or disulfram, is as yet unstudied in this population, but should be considered.

Substance abuse among patients with bipolar disorder should not be ignored because it is one of the major factors in medication noncompliance and suicidality (

12). Thus it has a major impact on the morbidity and mortality associated with bipolar disorder.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is another psychiatric disorder that commonly occurs with bipolar disorder. Winokur and colleagues (

19) reported that patients with bipolar disorder had significantly higher rates of childhood ADHD compared with patients with major depression. Similarly, in a family study of adolescent bipolar disorder, 24 percent of the adolescent probands had a history of ADHD (

81).

As with the substance use disorders, differential diagnosis is somewhat difficult. Symptoms of ADHD include poor concentration, distractibility, impulsivity, restlessness, and agitation, which are also features of a manic or hypomanic episode. The similarities can be particularly problematic because the first-line treatments for ADHD—stimulants and antidepressant drugs—are relatively contraindicated for individuals with bipolar disorder.

A diagnosis of ADHD should not be made if the individual is in the midst of a manic or hypomanic episode. The mania should be aggressively treated, and when the patient's mood is stabilized, ADHD symptoms can be assessed. In making the distinction between bipolar disorder and ADHD on a historical basis, it is important to inquire about the episodic or chronic nature of the symptoms and about symptoms that are more specific to mania, such as elated mood, grandiosity, hypersexuality, and decreased need for sleep. Finally, if a decision is made to treat ADHD in an individual with bipolar disorder, it is important to avoid agents that might precipitate mania or worsen the course of bipolar disorder. Clonidine may be a reasonable alternative to stimulants or antidepressants (

82).

Several investigators have reported higher rates of panic disorder among individuals with bipolar disorder than would be expected from the prevalence rates of panic disorder in the general population (

70,

71,

83). Although further study of this relationship is necessary, it is likely that untreated panic disorder and other anxiety disorders may worsen the course and prognosis of bipolar disorder. As with the treatment of ADHD, many of the first-line pharmacologic treatments for panic disorder and other anxiety disorders—antidepressants—can precipitate mania and must be used with caution in treating individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder and panic disorder. Consideration should be given to alternative strategies, such as use of valproic acid, which may be helpful in the treatment of both panic disorder (

84) and bipolar disorder (

26).

Several recent studies have also demonstrated relatively high rates of co-occurrence of obsessive-compulsive disorder with bipolar disorder. Boyd and colleagues (

83), in an analysis of ECA data, found obsessive-compulsive disorder to be much more common among individuals with bipolar disorder than in the general population (odds ratio of 18). Other studies have found high rates of comorbid mania among patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (

85,

86).

In general, much remains unclear about the relationship of these disorders to each other. Obsessive-compulsive disorder among patients with bipolar disorder may be related to the presence of depressive symptoms during mania, or the obsessive-compulsive symptoms may be an atypical presentation of depression during the course of bipolar disorder. In any case, as with the disorders previously discussed, this comorbidity has important treatment implications because many medications used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder can precipitate mania. Reports from clinical trials of antidepressants involving patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder have suggested that as many as 20 percent of patients may develop mania during antidepressant treatment (

87).

The relationship between bipolar disorder and personality is a complex one, both from a theoretical and from a diagnostic perspective. The differentiation of enduring personality characteristics from changes that occur as a result of acute illness can be particularly difficult with affective illness because affect is one of the contexts through which personality is expressed. Akiskal and colleagues (

88) have outlined a number of possible relationships between bipolar disorder and personality disorders, and the area is also well discussed in a recent review (

17).

Studies of specific personality disorders among patients with bipolar disorder have found high rates of cluster B diagnoses and particularly high rates of borderline personality disorder (

89,

90). However, the literature has numerous reports of bipolar-spectrum disorders misdiagnosed as borderline personality disorder (

91), and many of the criteria for borderline personality disorder and hypomania overlap.

Although a thorough review of the many complexities in this area is beyond the scope of this review, it is important to keep in mind that the symptom overlap between bipolar disorder and several personality disorders is substantial. The overlap is particularly pertinent when considering hypomania, cyclothymia, or more subtle affective disorder diagnoses. Diagnoses of personality disorder among patients with bipolar disorder should be made during times of affective stability to ensure the most accurate diagnosis.

Natural history and course

The first episode of bipolar disorder may be manic, hypomanic, mixed, or depressive. The natural course of bipolar disorder is characterized by high rates of relapse and recurrence (

12) at rates of 80 to 90 percent (

79). In prospective outcome studies extending up to four years, less than half of patients followed after an initial manic episode had sustained a good response to treatment (

79). Full functional recovery between affective episodes often lags behind symptomatic recovery (

59,

92). Following recovery from a mood episode, patients with bipolar disorder had an average of .6 episodes per year over a five-year period (

19). Compared with multiple-episode mania, first-episode mania was associated with a significantly shorter hospitalization; however, gender, age at onset of illness, comorbidity, and family history were similarly distributed in the two groups (

93). Data have largely been derived from naturalistic studies, in which treatment is prescribed by clinicians in response to patients' needs and becomes an outcome in itself, as the clinical condition largely determines the choice of treatment. In controlled trials, treatments are standardized, but the study population is likely to be biased by an increased adherence to treatment regimens. Therefore, data from naturalistic studies may better represent the course of patients under typical clinical conditions.

Many questions about the predictors of recurrence remain. The cumulative probability of recurrence has been reported to be more than 50 percent during the first year of follow-up, about 70 percent by the end of four years, and nearly 90 percent by five years (

79,

94). Recurrence of mood episodes has been associated with comorbid nonaffective psychiatric disorder, particularly substance abuse; the presence of psychotic features; and a family history of mania or schizoaffective mania (

68). One study found that patients who are symptomatic six months after their first episode had a 45 percent greater chance of experiencing a recurrence of mania or major depression at least once during the remainder of a four-year study (

79). There are conflicting data about whether age at illness onset, gender, premorbid psychosocial functioning, number of years of illness, and number of prior episodes predict recurrence (

68). As stated before, after gradual versus rapid discontinuation of lithium, the overall median time to recurrence was found to be 20 months and four months, respectively (

25).

Preliminary data about the efficacy of maintenance treatment with mood stabilizers have been published, but further studies are needed. A review of pharmacologic maintenance therapies reported that approximately 33 percent of patients on lithium remained symptom free at five years, and that combining lithium with other mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, or antipsychotics may provide greater prophylaxis (

95). Patients with lithium blood levels greater that .8 mEq/L clearly have a better outcome (

95). Several studies reported equivalent efficacy of carbamazepine and lithium for maintenance therapy, but methodological flaws raise serious questions about the results (

96).

A recent randomized trial involving 144 patients that compared lithium to carbamazepine found no differences in rates of hospitalization and recurrence at 2.5-year follow-up (

96). However, lithium was superior in preventing recurrences when combined with other medications, and fewer patients had side effects that prompted its discontinuation. As a result, recurrence among patients who completed the study was less frequent among patients who received lithium (28 percent) than among those who received carbamazepine (47 percent) (

96). In one study full compliance with maintenance therapy over a one-year period was accomplished by only 49 percent of patients (

97).