Risperidone, a novel antipsychotic agent, is similar if not superior to standard neuroleptics in its effectiveness in treating the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (

1,

2,

3). However, risperidone is more expensive than traditional antipsychotics, which has caused some public mental health agencies to restrict its use. Such policies are shortsighted if risperidone's possibly superior effectiveness and preferable side-effect profile produce improved medication compliance, better outcomes, and lower total treatment costs.

Few studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of risperidone. Addington and colleagues (

4) found that patients used 73 percent fewer hospital days over one year after beginning risperidone. Lindstöm and associates (

5) found a 31 percent decrease in hospital days over a one-year period among patients treated with risperidone, and 54 percent of those subjects showed improvement on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. However, both studies analyzed small samples of responders (14 and 32 subjects, respectively).

Albright and coworkers (

6) found a 60 percent reduction in hospital admissions and a 58 percent decline in hospital stay among 146 patients after they started risperidone, leading to a $7,925 cost savings (Canadian dollars) per patient. Viale and colleagues (

7) reported a 26 percent reduction in inpatient stays and a 57 percent decline in utilization of residential treatment among 139 patients starting risperidone. Nevertheless, given increased utilization of lower-cost services, they found a 3.4 percent increase in total psychiatric treatment costs after initiation of risperidone. All of these studies were limited by mirror-image designs that could not distinguish treatment effects from variation in the natural course of illness or changes in the health care system. Only the Lindström study included an effectiveness measure.

The study reported here is a retrospective, quasiexperimental study comparing patients on risperidone with a matched group treated with standard antipsychotics. The study assesses the effectiveness of risperidone in ordinary clinical practice. It is based on an intent-to-treat model in which subjects may have other medication changes after initiation of risperidone. The primary hypothesis was that among outpatients with schizophrenia, initiating risperidone treatment results in reduced symptoms, improved functioning, and lower total treatment costs compared with continued treatment with standard neuroleptics.

Methods

Subjects

We identified all individuals in the database of the San Francisco Department of Mental Health Services who were treated as outpatients between February 1, 1993, and June 31, 1995, had a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and were between 18 and 65 years old. We reviewed the medication histories of all eligible patients. Those who received risperidone between February 1, 1994, and July 1, 1994, constituted the risperidone group. Comparison-group patients had never received risperidone.

We identified 1,865 eligible patients, 560 of whose charts were unavailable at screening. We dropped all subjects who had received clozapine previously or during the study period and subjects in the risperidone group whose records did not indicate a starting date for risperidone.

Fifty-six patients who met criteria for the risperidone group were matched with 56 patients who had not received risperidone on age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, medication clinic site, diagnosis, and number of psychiatric emergency visits in 1993. The latter variable was the best available indicator of illness severity.

Procedures

Data on level of functioning, symptomatology, medication prescriptions, and service utilization were abstracted from subjects' outpatient charts. For each risperidone user and a matched comparison subject, we collected data for 12 months before initiation of risperidone and 12 months after. Demographic data were obtained from the computer database.

Monthly Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores were the primary measure of the effectiveness of the medications. GAF scores can range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. These scores were not clinician ratings but were assigned by trained research assistants based on chart review. Initial efforts to keep the rater blind to the patients' treatment group were abandoned because the clinical records made the treatment group obvious.

The Global Assessment Scale (GAS), the earlier version of the GAF, has demonstrated concurrent validity with symptom rating scales and global measures of psychiatric impairment and is sensitive to clinical changes over time (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15). GAS scores based on review of records have acceptable validity and good reliability whether scoring is per episode or over a year's time (

8,

14,

15). We computed intraclass correlation coefficients on scores of 22 independently rated subjects to examine interrater reliability.

We collected monthly utilization data on psychiatric services within the county mental health system or private hospitals paid by the county or MediCal. Data on outpatient treatment, including visits for individual therapy, group therapy, medication, and day treatment, and data on laboratory tests were obtained through chart review. We reviewed outpatient charts for medication information and private hospitalization data. The computer database provided data on use of acute hospital services, acute diversion units, residential day treatment, care in skilled nursing and residential facilities, and psychiatric emergency services.

Cost estimation

We calculated treatment costs by multiplying raw units of service by their estimated cost. The value of mental health services was calculated as an average of the costs of similar services as reported in the county year-end cost report for 1994, the latest year for which cost data were available. Standard accounting procedures were used to determine the unit costs of each type of service at each facility.

Laboratory costs were based on the 1995 SmithKline Beecham Clinical Laboratories price list. We calculated medication costs by multiplying the quantity prescribed by the wholesale price per pill based on a 100-tablet bottle. The price per pill of generic medications was calculated by averaging the average wholesale price based on a commercial distributor price list (Whitmire Distribution Corporation, Union City, New Jersey, August 1995).

Statistical analysis

Power analysis of repeated-measures analysis of variance indicated that a sample size of 56 subjects in each group was adequate to reveal a medium effect size for an alpha of .05 and power of .80 (

16). The two groups' demographic data were compared using the Student's t test or chi square test as appropriate. Primary analyses were done using repeated-measures analyses with serial correlation and random patient effect in which treatment group was the independent variable and monthly cost and outcome (GAF score) were the dependent variables (

17).

Because cost variables are highly skewed, such data are often logarithmically transformed. Payers, however, do not have the luxury of transforming costs or ignoring costly patients. Thus we analyzed outcomes in their raw form, using statistical methods that accurately account for severely nonnormally distributed data (

18,

19). We used repeated-measures models to estimate the effects of treatment on cost measures. We then used permutation tests and the bootstrap percentile method to produce valid confidence intervals and p values for the nonnormal data.

Permutation tests estimate how large the treatment effect would tend to be under the null hypothesis that treatment group is irrelevant to outcome. We determined the estimated treatment effect by randomly assigning group membership and obtaining estimates under multiple random assignments 1,000 times, calculating the permutation test p value as the number of random assignments that produce larger estimates than the actual estimate (in absolute magnitude, for a two-sided test) divided by 1,000. Bootstrap methods are based on drawing numerous samples, with replacement of subjects, and obtaining a new effect estimate, called a bootstrap estimate, for each sample.

Because the risperidone group was defined by treatment initiation, all subjects received medication in the first month of the follow-up period. This was not necessarily true of the comparison group. We evaluated this potential bias using life table analyses in which no medication prescription was the failure point based on the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method.

Results

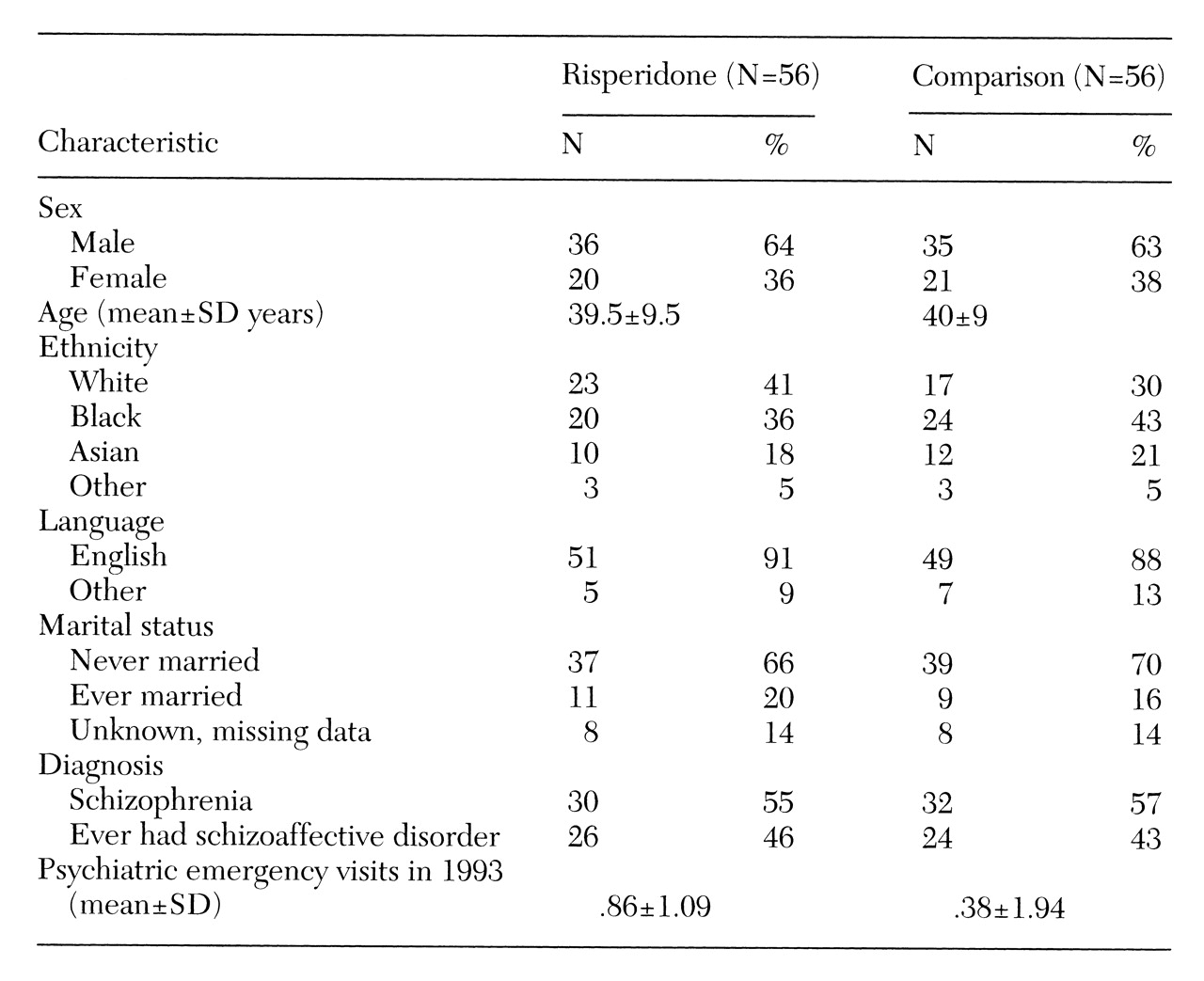

No statistically significant differences were found between the risperidone and comparison groups in age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, diagnosis, or number of emergency visits in 1993 (

Table 1). Interrater reliability on the GAF scores was good (intraclass correlation coefficient=.77).

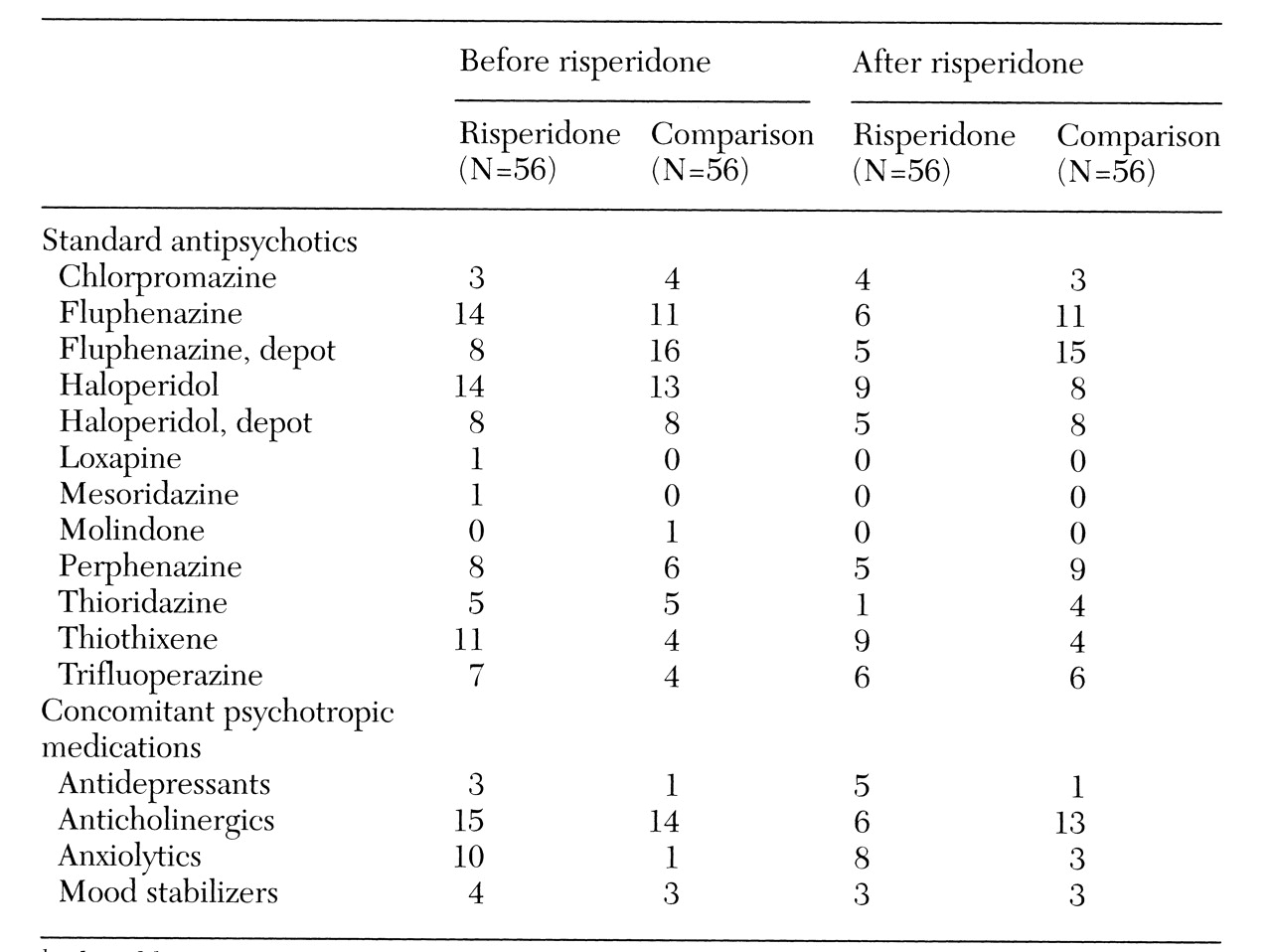

Table 2 summarizes information on the medications used by subjects during the study period.

The average GAF scores of the risperidone group (32.2±5.4) and the comparison group (33.9±6) during the prerisperidone period were not statistically different, further supporting the groups' comparability. The average GAF scores in the postrisperidone period (32.2± 4.3 for the risperidone group and 34.3±5.4 for the comparison group) were significantly different (t= 2.255, df=110, p=.03), but this analysis did not control for baseline scores. The more comprehensive mixed-model repeated-measures analysis, which took GAF scores from the prerisperidone period into account, revealed no group differences in monthly GAF scores over the course of the study period.

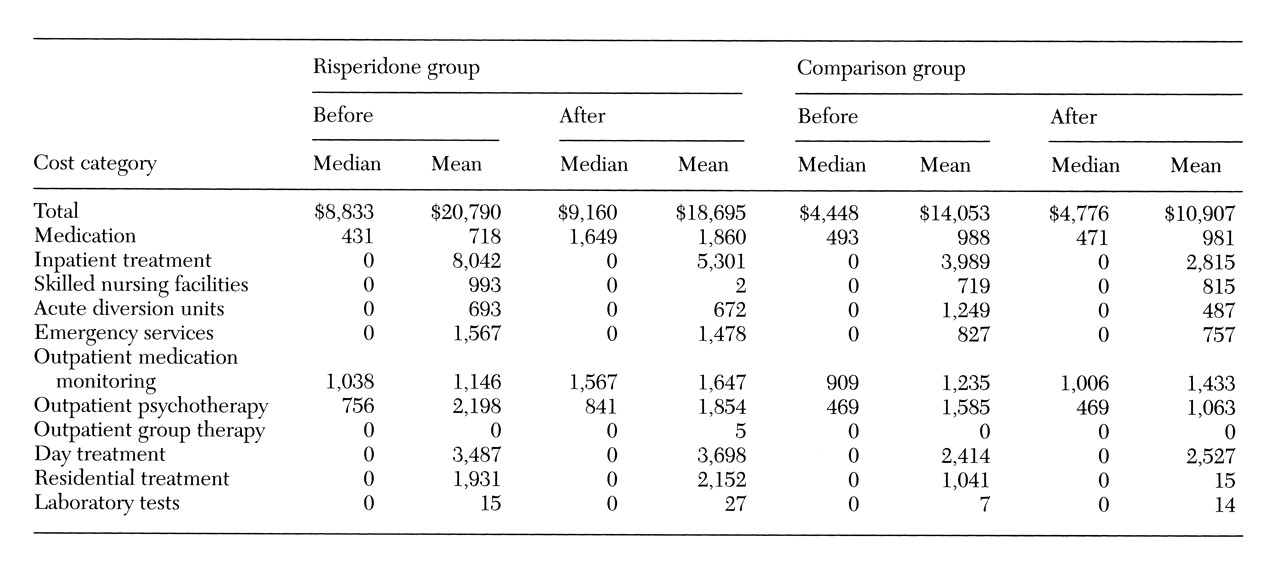

Cost data are summarized in

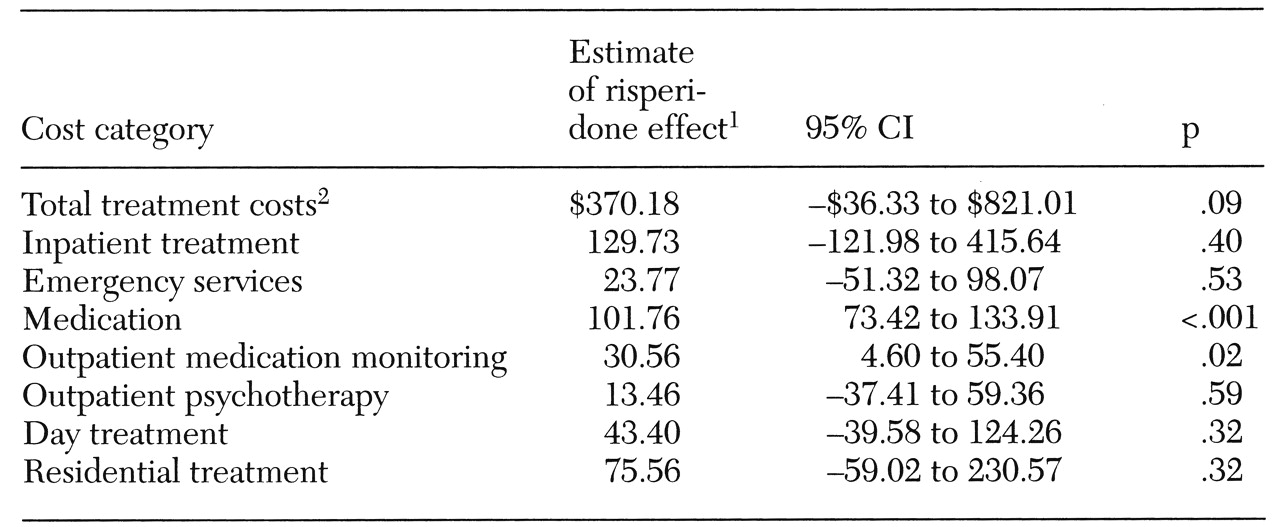

Table 3. The mixed-model analyses of treatment cost are shown in

Table 4. Although

Table 3 indicates that the risperidone group generally had higher treatment costs in the prerisperidone period, the repeated-measures analysis controls for this difference. Total treatment costs for the groups were not significantly different, although there was a trend toward higher costs in the risperidone group (estimate=$370.18, p=.08, 95 percent confidence interval (CI)=−$36.33 to $821.01).

These results indicate that the total monthly treatment costs for a patient on risperidone were approximately $370 higher than for a patient receiving standard antipsychotics. Costs directly associated with the use of risperidone appear to explain this trend. The only statistically significant group differences in treatment cost were for medication and for outpatient medication visits. Each month, subjects on risperidone incurred approximately $102 more in medication costs (p<.001, 95 percent CI=$73.42 to $133.91) and $31 more in medication visit costs (p=.02, 95 percent CI= $4.60 to $55.40) than did comparison subjects. Costs associated with care in skilled nursing and acute residential facilities, outpatient group therapy, and laboratory tests were included in the total cost, but these services were used too rarely to analyze separately.

Life-table analysis of the time to the first month without a medication prescription indicated that medication usage between the groups was comparable at the time of risperidone initiation (log-rank test, χ2=.012, df=1, p=.92).

Discussion

Compared with previous studies of the cost of risperidone, the strength of this study is its use of a matched comparison rather than a mirror-image design. In addition, this study examined treatment effectiveness as well as cost. In contrast to some previous studies, we did not see a significant decrease in service utilization to compensate for the higher cost of risperidone. If anything, we saw a trend toward higher total costs in the risperidone group, attributable to higher medication-related treatment costs. This finding is similar to that of Viale and colleagues (

7), who reported a 3.4 percent increase in total treatment costs with risperidone. Our matched comparison design provides greater confidence that no significant change in utilization occurred.

Nevertheless, because we did not do a randomized, controlled study, reasonable doubts about the comparability of the two study groups exist. For example, the risperidone group was selected on the basis of a medication change, while the comparison group was not, and the risperidone group had higher service utilization in the prerisperidone period. We attempted to minimize this potential sample bias by using statistical techniques that take into account cost and effectiveness data from the prerisperidone period.

Several hypotheses could account for initiation of risperidone for the patients who constituted the risperidone group. They might have been doing poorly at the time of medication change, they might have had side effects on standard antipsychotics, or they might have had poor baseline symptom measures. However, members of the comparison group might have been offered a new medication for these same reasons but declined. In any event, it is more likely that selection bias would have resulted in a sicker or more difficult risperidone group. Thus the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups probably indicates at least that risperidone treatment is not significantly less effective or more costly than standard antipsychotics.

Naturalistic studies examining actual clinical situations generally tend to have weaknesses in internal validity but may have certain strengths in terms of external validity. For instance, this study may better reflect everyday treatment than would a randomized, controlled study. The possible selection bias toward more difficult patients receiving a trial of new medication most likely reflects actual clinical experience.

The results suggest that risperidone's effectiveness is comparable but not superior to that of other antipsychotic medications. We found no statistical differences in GAF scores between the risperidone group and the comparison group, although the sample size was not large enough to reveal a small difference. On the other hand, a small difference between GAF scores is probably not clinically important. If we had been able to use a scale that was more sensitive to clinical change, we might have found a significant difference, but the lack of such differences may be sufficient to inform policy makers, who are less concerned about small clinical changes. It is worth noting that the GAF scale has significant limitations in measuring negative symptoms, which may underestimate the effectiveness of risperidone treatment.

As mentioned, the two groups differed in their selection based on a medication change. There is evidence that any change in medications can lead to an increased risk of relapse among patients with schizophrenia. Gardos (

20) found that switching patients with schizophrenia from stable antipsychotic regimens to equivalent doses of other antipsychotics was associated with an increased risk of relapse, apparent after three months and peaking at about one year. Gardos defined relapse as a significant increase in symptomatology, and this increase may be associated with higher treatment costs. Only five comparison subjects had a medication switch in the first postrisperidone month. Thus subjects in the risperidone group were less stable in terms of their medication and possibly less clinically stable in general.

To further examine the effect of medication changes, we performed life-table analysis of emergency visits using the first visit to the psychiatric emergency room as the failure point. There was a trend for patients in the risperidone group to require emergency services sooner than the comparison group (log-rank test, χ2=3.696, df=1, p=.06). This effect was largely explained by emergency visits within the first four months of risperidone initiation by subjects who did not make emergency visits in the previous year.

However, life-table analysis of the time to first hospitalization did not reveal any group differences. The emergency room result differed from the survival analysis of time to missed medication prescriptions, indicating that the trend to increased emergency visits in the risperidone group resulted from medication change, rather than from missed medication. Thus our data were consistent with Gardos's hypothesis of a destabilizing effect of medication changes. This effect may lead to increased costs in any cost study of new medications, but the effect would likely decrease over time in longer-term studies.

Conclusions

This study did not reveal a statistically significant difference between a group treated with risperidone and a group remaining on standard antipsychotics in global effectiveness of treatment or total treatment costs. However, a trend toward increased total costs in the risperidone group was attributable to medication costs. Despite the lack of evidence for greater effectiveness or cost savings with risperidone, the research literature clearly points to a reduction in side effects. Given the likely selection bias towards a sicker or more difficult risperidone group in this matched, comparison study, these results suggest that a general policy of restricting use of risperidone has no significant cost-saving advantage.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Susan Hansen, M.D., Irwin Shapiro, M.D., Louise Holland, L.P.T., and Karen Brandenberger, L.P.T., of San Francisco Citywide Case Management for help in the initiation and conduct of this project and Peter Bacchetti, Ph.D., for advice about statistics. This study was supported by grant RIS-OUT-03 from Janssen Pharmaceutica and grant MH-43694 from the National Institute of Mental Health.