Psychotropic medication is an effective component of treatment for major depression (

1). However, little research has examined demographic differences among individuals with depression who chose either to use or not to use pharmacological interventions. Most of these studies have included very small samples or samples composed primarily of patients with psychotic disorders, and they have yielded mixed results (

2,

3,

4,

5). Moreover, these studies focused on individuals currently receiving some form of mental health treatment, thus excluding those who are not engaged with a treatment provider (

6).

The study reported here sought to address these limitations by examining medication use in a nationally representative household-based sample. Specifically, this research investigated the association between various demographic factors and self-reported use of medication among persons identifying themselves as having major depression.

Methods

The National Health Interview Survey is a nationwide household interview survey that uses a multistage sample design to accurately represent the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States (

7). Because the sample is designed to be representative of the population, individual subjects are assigned different weighted values to accurately estimate the number of individuals in the United States who would respond positively to each question. The 1994 survey achieved a 94.1 percent interviewed rate, or 25,705 households, resulting in a sample size of 116,179 individuals. The respondent refusal rate was 4.2 percent, with the remaining 1.7 percent representing households where, despite repeated calls, an eligible respondent was not available.

The study identified a subsample of 1,189 persons who responded positively when asked if they had experienced major depression in the past 12 months. Applying the weighted values described above to this subsample provided a population estimate of 2,927,576 individuals in the United States who reported experiencing an episode of major depression during the previous 12 months.

Of the subsample of 1,189 individuals, 66.4 percent were female. The age range was from 18 to over 75, with more than half (52.4 percent) between 25 to 44 years. The subsample was primarily white (86.1 percent), with blacks and others making up 10.2 percent and 3.8 percent, respectively.

A quarter of the respondents reported being separated or divorced (26.4 percent), with smaller percentages reporting never having been married (18.9 percent) or being widowed (7.9 percent). The educational level of individuals in the subsample ranged from less than elementary school through graduate school; the largest percentage of respondents had a high school education (35.7 percent). Most respondents described their income as being between $5,000 and $15,000 a year (30.8 percent), although reported annual incomes ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $50,000. Most subjects classified their health as generally being in the fair to good range (50.1 percent).

Results

More than a third of individuals in the subsample (34.2 percent) who reported suffering from major depression responded negatively to the question "In the past 12 months have you taken prescription medication for any ongoing mental or emotional condition?"

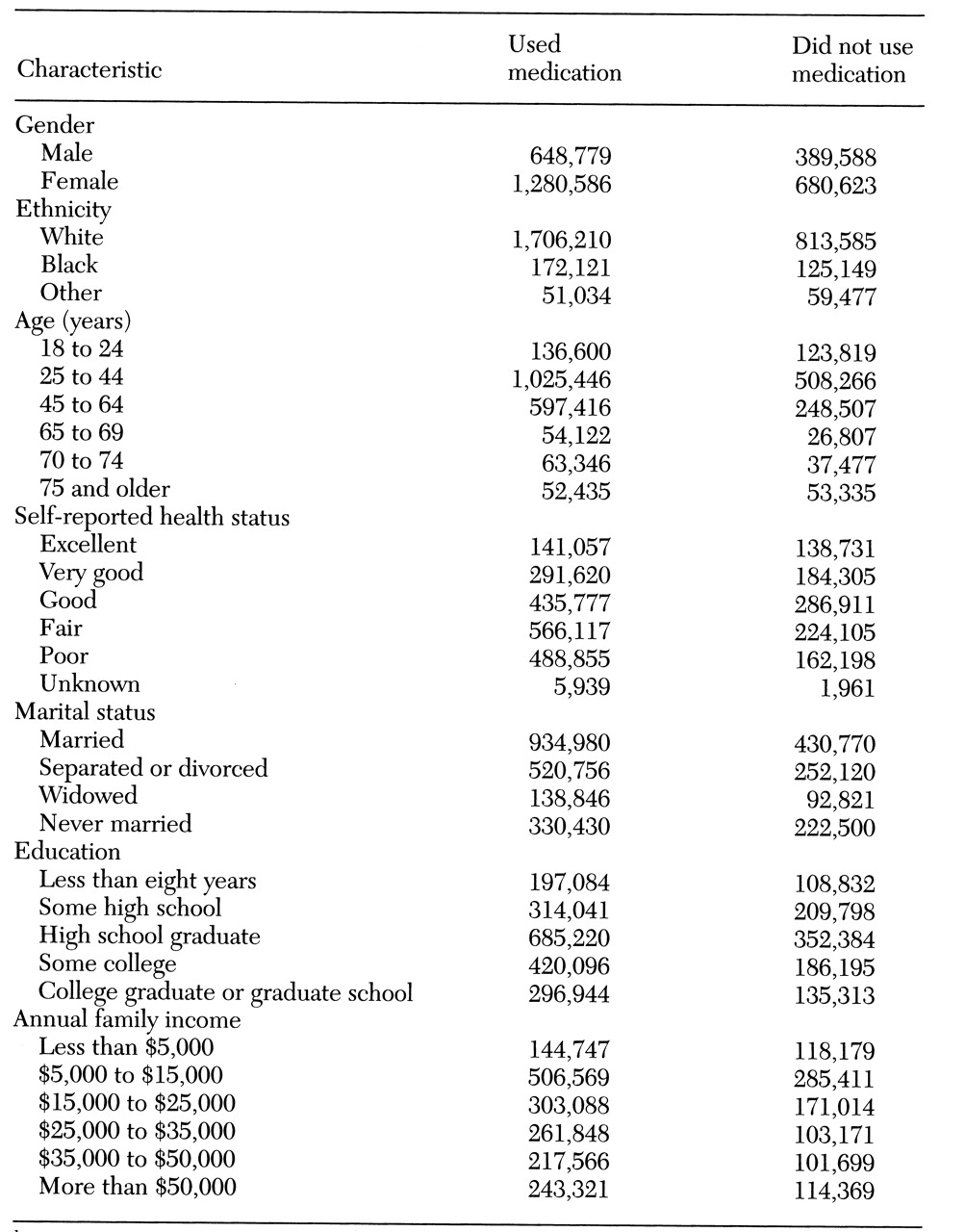

Table 1 shows the population estimates for the demographic factors associated with use and nonuse of medication.

Age was significantly related to medication use (χ2=15.92, df=5, p>.01; N=1,189), with the lowest percentage of use noted among the youngest and the oldest age groups (54.4 percent among 18- to 24-year-olds, and 50 percent among those age 75 and older). Members of minority groups were less likely than whites to have used medication within the last 12 months (χ2=10.30, df=2, p>.01; N=1,189). More than two-thirds of whites (67.6 percent) reported taking some medication in the last year, but only 56.5 percent of blacks and 51.2 percent of members of other minority groups did. Males were less likely than females to have used medication in the last 12 months (61.4 percent, compared with 68 percent; χ2=5.08, df=1, p>.03; N=1,189). In addition, self-reported health status, which could range from excellent to poor, was associated with medication use (χ2=28.67, df=5, p>.001; N=1,189). Those describing themselves as being in excellent health were least likely to have taken any prescription medication for their psychiatric disorder (51.7 percent), while those in poor health were most likely to have done so (75 percent).

A trend was noted for those who were widowed (60.6 percent) and never married (59.4 percent) to be less likely to use medications than those who were currently married (68.3 percent) or divorced or separated (67.2 percent) (χ2=7.01, df=3, p>.08; N=1,187). Those with the lowest incomes were most likely to report not using medication in the last 12 months (45.8 percent; χ2=11.03, df=5, p>.06; N=1,047). Educational level was not significantly associated with medication use.

Discussion and conclusions

In a nationally representative household-based sample, more than a third of individuals who identified themselves as having major depression reported not taking any prescription medication for their psychiatric condition in the last year. The results suggest that males, minorities, and those reporting excellent health status are less likely to use medication. These findings also indicate that individuals at either end of the age continuum use medication less than those in other age groups. In addition, lower-income, widowed, and never-married individuals showed a trend toward being less likely to use medication.

Population estimates of individuals with major depression from the 1994 National Health Interview Survey were somewhat lower than those from previous epidemiological surveys (

8,

9). At least two possible reasons may account for these differences. First, the self-report nature of the data may have artificially lowered these estimates. Stigma, lack of insight, and potential reluctance of subjects to identify themselves as having a diagnosis rather than individual symptoms may all have contributed to lowered rates of reporting major depression in this study.

Second, the sampling frame for the 1994 survey excluded hospitals, prisons, group homes and other institutions and residential settings not identified as households, potentially leading to an underestimate of major depression in the general population. Despite the lower prevalence estimate of major depression in the 1994 survey, several demographic trends found to be associated with depression—gender, income, and ethnicity—parallel those found among individuals with major depression in other epidemiological surveys (

10).

This study assessed self-reported use of medication for any ongoing emotional condition among individuals who identified themselves as having major depression within the past year. However, it is important to note that several factors can influence a patient's medication use, including the provider's willingness to prescribe medication, the patient's willingness to consider pharmacological treatment, and the patient's compliance with a prescribed medication regimen. Future research is needed to assess the relative contribution of these variables in explaining the limited use of medication among various demographic subgroups of individuals with major depression.

Despite the limitations of the study, it used a nationally representative household-based sample, and thus it provides an important step in accurately assessing demographic factors associated with medication nonuse among individuals who identify themselves as having major depression. Understanding which subgroups are less likely to use medication is important to providers as they attempt to select the most effective treatment strategies and enlist patients' cooperation in the treatment process.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Center for Health Statistics for use of the data and Henry Krakauer, Ph.D., for assistance with data analysis.