Subjects

Subjects were recruited from a public-private mental health system in Baltimore County, Maryland, during the period from July 1993 to June 1995 as part of a study of cognitive deficits and social functioning among outpatients with schizophrenia (

12). Exclusionary criteria were current substance abuse, mental retardation, neurological disease, and age younger than 18 years or older than 65 years. All study participants provided informed consent.

The sample comprised 72 subjects, 50 of whom were men (69 percent). Subjects had a mean±SD age of 42.1±9.6 years. Their mean age at onset of illness was 20.9±6.1 years, and they had had a mean of 5.7±4.7 psychiatric hospitalizations. The majority of subjects—59 patients, or 82 percent—were single and had never been married; six patients, or 8 percent, were married; and seven patients, or 10 percent, were separated or divorced. Fifty-seven subjects, or 79 percent, were Caucasian; 14 subjects, or 20 percent, were African American; and one subject was Asian American. The study participants had an average of 13.6±2.1 years of education.

All but one subject was receiving antipsychotic medication at the time of residential assessment. The mean±SD dose in chlorpromazine equivalents was 539±591 mg. Thirty-one patients were receiving atypical antipsychotic medications. Subjects were assessed by their treating doctor as stable in their community functioning for at least one month before the assessment of residential independence, and no subjects had been hospitalized in the two months before the assessment.

Twenty-six patients met diagnostic criteria for schizoaffective disorder. The other patients met criteria for the following subtypes of schizophrenia: paranoid for 19 patients, undifferentiated for 18 patients, residual for seven patients, and disorganized for two patients.

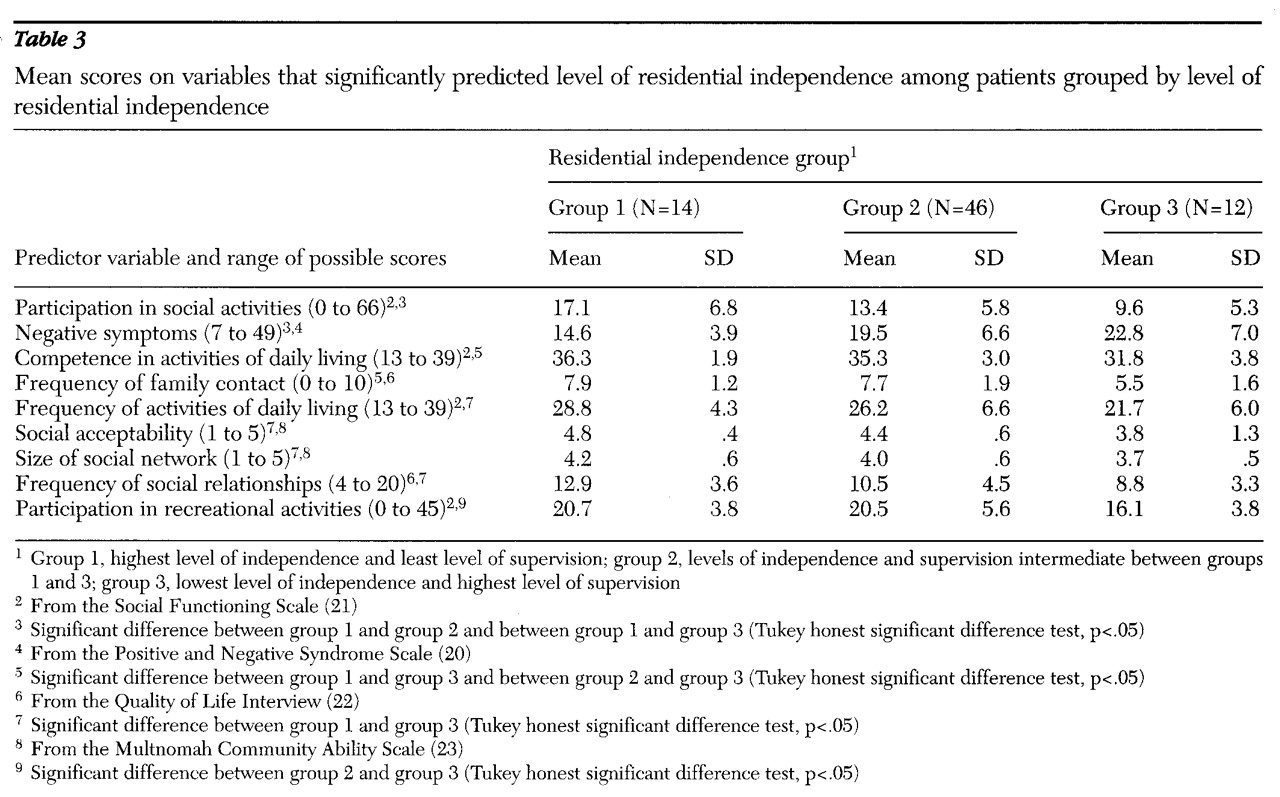

Subjects were classified into three groups based on their degree of residential independence. Group 1, the most independent group, included 14 patients who lived in their own residence without any supervision for at least the previous two months. To quality for this group, patients also had to participate in constructive activity outside of the home for more than 20 hours a week. Among the patients in group 1, seven were competitively employed, five attended a prevocational day program, and two were engaged in volunteer jobs.

Group 3, the most supervised group, included 12 patients who resided in settings such as group homes and highly supervised board-and-care residences where they received direct, on-site supervision for more than six hours a day.

Group 2 included 46 patients whose living arrangements were intermediate between group 1 and group 3. Among group 2 patients, 15 lived with their parents, two lived with other nonspouse extended-family caregivers, 14 lived in apartments with drop-in supervision, 13 lived independently but did not meet the group 1 criterion of daytime activity, and two had moved to their own unsupervised, independent apartment within the previous two months.

Measures and procedures

A battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to all patients at the time of their initial recruitment. The tests included the vocabulary, arithmetic, digit span, block design, digit symbol, and picture arrangement subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-R) (

13); the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (

14); the Logical Memory test; the Rey-Osterreith Complex Figure Test (

15), including the copy and recall test; the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (

16); the Trail Making Test (

17); the Halstead-Wepman Aphasia Screening Test (

18); and the Chicago Word Fluency Test (

19).

At two-year follow-up the subjects' symptoms, social functioning, and residential status were assessed. Symptoms were rated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (

20) by raters who showed acceptable interrater reliability on the PANSS symptom factors (r=.88 for the positive symptom factor, .74 for the negative symptom factor, and .82 for the general symptom factor). Subjects were administered the Social Functioning Scale (SFS), which asks about their abilities in seven areas—activation-engagement, interpersonal communication, frequency of activities of daily living, competence at activities of daily living, participation in social activities, participation in recreational activities, and employment or occupational activity (

21).

When possible, an informant who lived with or cared for the patient was also interviewed using an informant version of the SFS, and the average ratings were used in the data analysis. Interviews with such informants were available for 38 subjects, or 53 percent.

Patients also were administered the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI), a self-report instrument inquiring about eight life domains—living situation, daily activities, family contact, social relations, legal and safety issues, health, finances, and school or work activities (

22). Subjects were also rated by the first author using the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (

23); all available information was used in making these ratings. The neuropsychological, symptom, and social functioning measures were selected to provide a comprehensive assessment of patients' functioning in these domains.

Data analysis

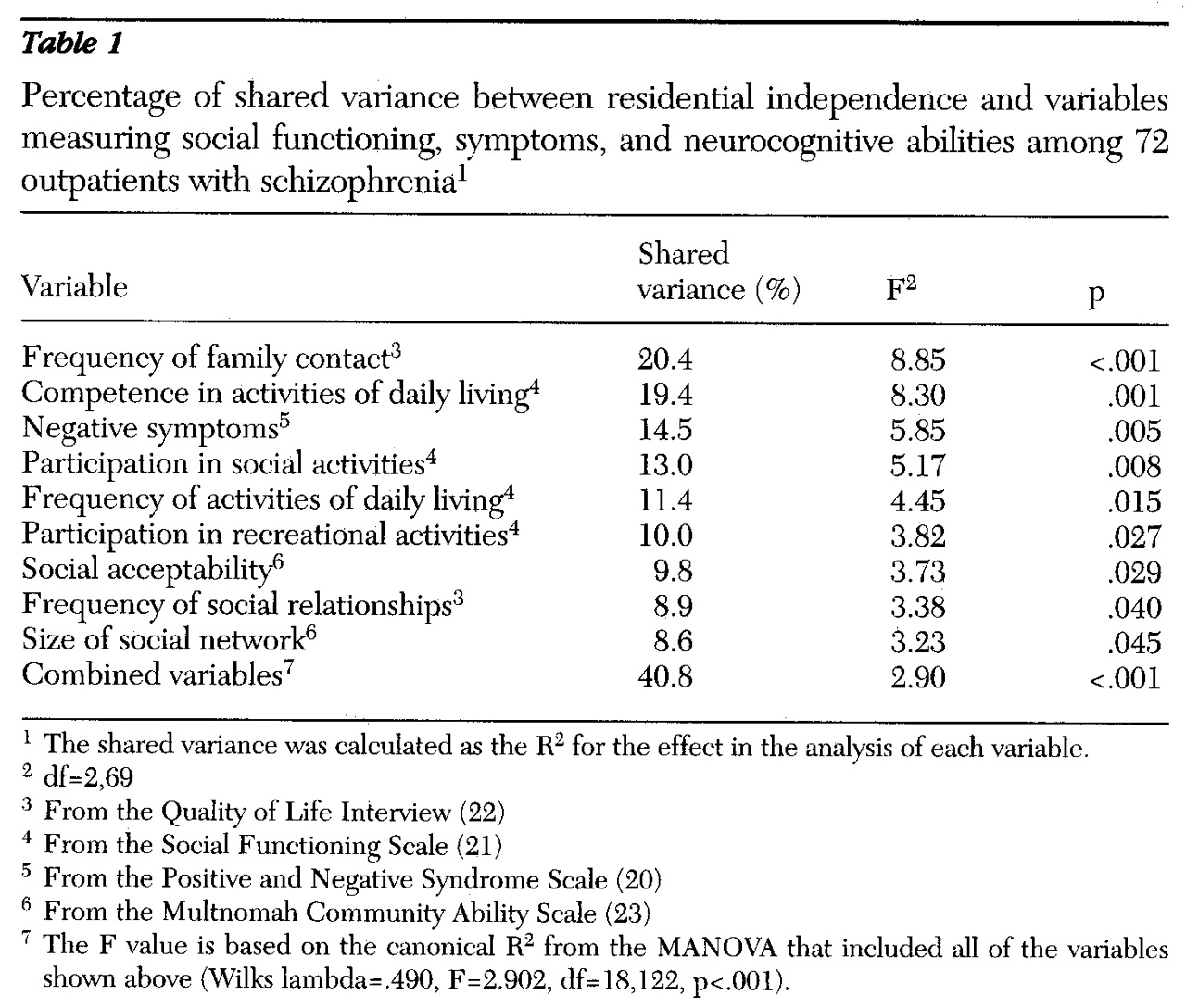

Univariate analyses of variance were used to determine the percentage of variance that was shared between patients' residential independence and each study variable. Study variables included demographic characteristics, PANSS factor scores, SFS scores, Multnomah item scores, and QOLI objective scores. Three variables were excluded from these analyses because the ratings were confounded by patients' residential status: the Multnomah scale items about money management and independence in daily life and the SFS employment rating. In addition, gender was not analyzed because it is a dichotomous variable.

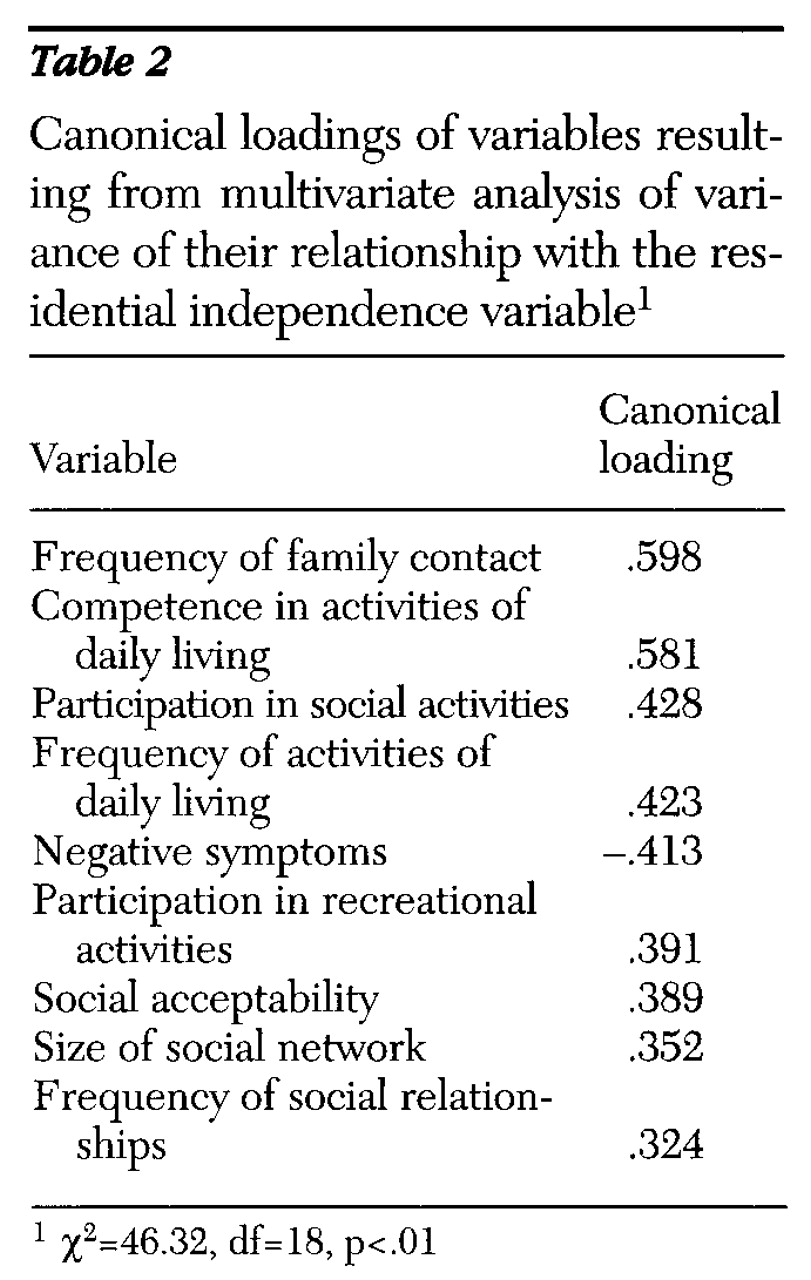

Study variables that shared a significant percentage of variance (p<.05) with the residential independence variable were included in a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) (

24). The MANOVA was performed to determine the relative contribution of the variables in a discriminant function. We calculated canonical loadings, which are the correlations of each variable with the linear combination of variables in its set; they index the importance of each variable in relation to the residential independence variable. We also derived a classification table from the MANOVA discriminant function. All possible pairwise post hoc contrasts were computed between the residential groups using the Tukey honest significant difference test.