The process

When the reorganization process began, no one on our team had a clear vision of the final product. However, we did have several principles to guide our efforts. First, the program had to become more accessible and more efficient, which meant that the expensive inpatient program had to close. Second, we would have to treat a larger number of individual patients in the coming years because VA reimbursement would no longer be based on hospital bed days of care. Instead, it would be based on the number of unique patients treated per fiscal year (

4).

One of the major problems that we faced was staff anxiety and uncertainty about whether change would result in patients' receiving lower quality of care and in staff members' losing their jobs. These concerns were realistic. The reorganization described here did indeed result in many program changes, and we did lose staff, although they were absorbed by other hospital services. By involving staff members in a meaningful way in the reorganization, we were able to reduce anxiety and to reach consensus on major components of the new program. These goals were accomplished through a series of daily working lunch meetings with as many staff members who could attend over a period of two months.

Needs of patients and referring services

A key to any successful business is to know who your customers are. Only then can you meet your customers' needs. In our case, our customers consisted of patients and referring services. In past surveys, our patients told us that they wanted more individualized programs and more evening activities. The hospital staff who referred patients wanted faster responses to requests for consultation and shorter waiting times for patients to receive treatment. These requests became our goals.

Task forces that consisted of at least two staff members were assigned to unserved potential patient groups or services. Each task force was given about one week to investigate its subject area, collect data on the needs of patients and of staff members making referrals, and assess the feasibility of starting a new program to meet those needs. The task forces were then asked to present their findings and recommendations to our entire substance abuse team at daily lunch meetings.

After all the program possibilities were presented, staff had to reach agreement on which services would be most effective and would best meet the needs of our patients and referral sources. To make these decisions, we adopted three simple criteria: successful services are fast, good, and cheap. In our setting, these criteria translated into accessible, high-quality, and affordable patient care.

Program building blocks

Our first decision was to eliminate consultation waiting lists. We expanded our assessment team and made every effort to provide consultations on a same-day basis. This change increased access to all our programs and was appreciated by our patients and referring staff.

The first new component was a 16-bed residence, which was justified by our earlier study that found residential treatment more cost-effective than inpatient treatment (

5). The residence was needed because closure of the inpatient unit left us no way to treat homeless patients, those with transportation problems, and those residing in high-drug-use and stressful environments. We were able to convince the hospital administration to let us use some of the funds saved from closing the inpatient unit to establish the residence. We then contracted with a nearby community facility—a five- to ten-minute walk from the hospital—for 16 supervised residential beds at a cost of $600 per bed per month. The supervision is provided by non-VA staff.

Our second new component was an intensive outpatient day program. The day program operates Monday through Friday and offers 18 hours a week of group treatment as well as individual counseling. Most patients stay three weeks. Patients in the residential program are offered an additional 12 treatment hours a week. The additional treatment consists of four hours of craft groups, four hours of life skills groups, and a four-hour weekly outing supervised by recreational therapy staff. The residential patients also participate in group meetings and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) self-help groups at the residential facility in the evenings and on weekends.

After the intensive day program was set up, an intensive evening rehabilitation program was started for three nights a week from 5:30 to 7:30. The six- to eight-week program is designed for employed patients and those unable to attend the day program.

We developed a relapse prevention program, based on a cognitive-behavioral treatment model, that meets twice weekly for one hour for a period of six to eight weeks. This program serves patients who already understand the basic principles of substance abuse treatment and recovery and patients who do not agree with the 12-step philosophy of AA and NA.

An intervention program for people cited for driving under the influence (DUI) was developed for referrals from the county court. The DUI program is held one evening a week for one and a half hours for 12 weeks.

We developed a specialized program for women veterans, with a recovery group for those early in their treatment and an aftercare support group for those who understand and practice recovery.

An outpatient detoxification clinic was added and staffed by both nurses and physicians.

A domestic violence intervention program was initiated after staff received all the appropriate training. Patients are referred by the county court to complete a 28-week program. A support group is now offered in the posttraumatic stress disorder clinic for patients who also have substance abuse problems.

A preventive-educational service is also offered to other hospital programs and inpatient units that treat patients at high risk for substance abuse, such as inpatient psychiatry wards and the day treatment and homeless programs.

The three aftercare groups that were part of the former program continue to meet once weekly in the evening and daytime.

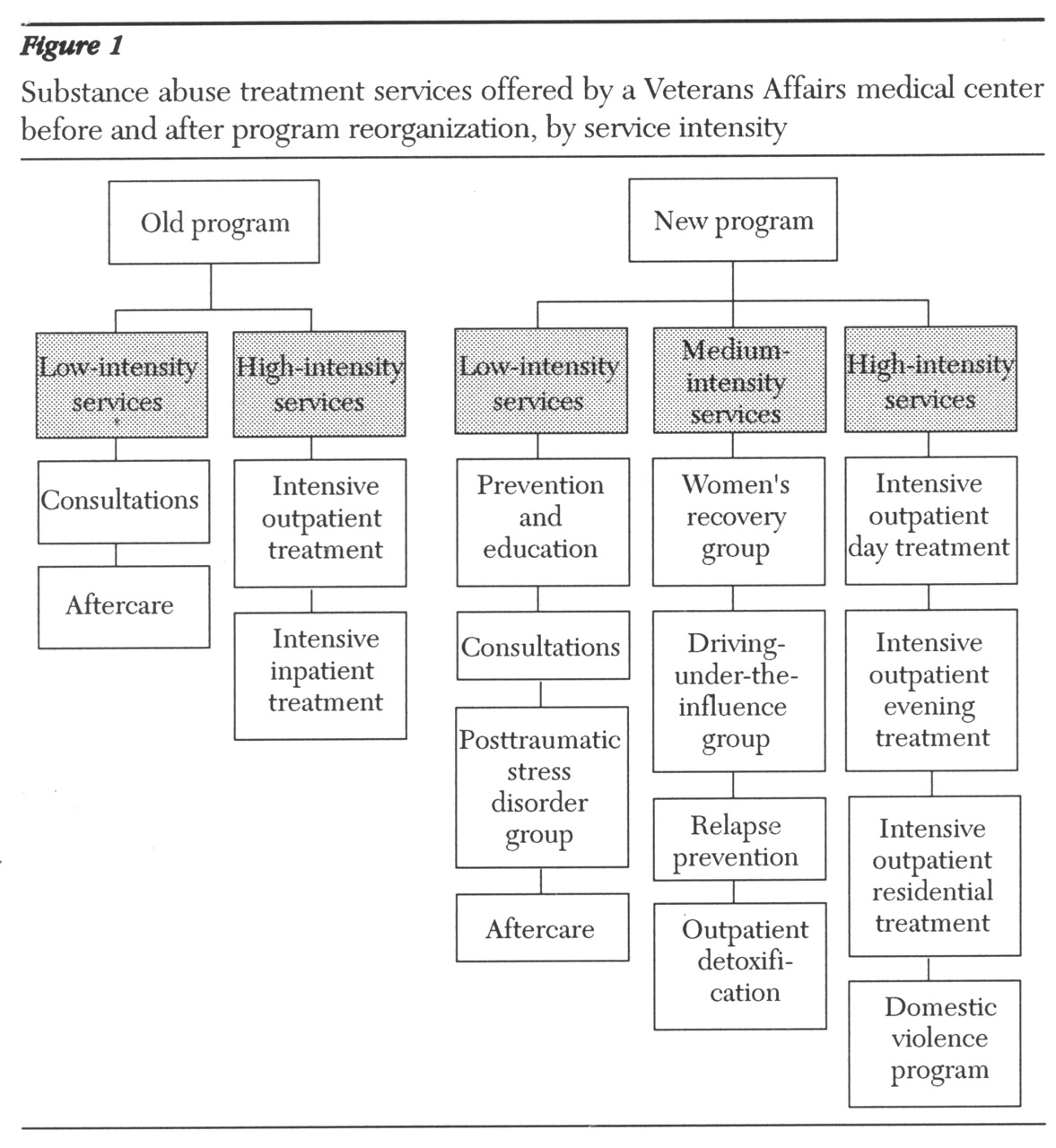

Figure 1 illustrates the changes made in the program, and lists services offered according to treatment intensity.

Integration of inpatient and outpatient staff

Our old program had a small outpatient team and a large inpatient team. The inpatient component of the old program consisted of two psychiatrists, one nurse practitioner, four addiction counselors, one social worker, eight registered nurses, two nursing assistants, one psychologist, and a unit clerk. The outpatient component consisted of one half-time psychiatrist, two addiction counselors, one clinical nurse specialist, one psychologist, and one administrative program assistant.

The new program brought all the staff into one location. Several staff members were transferred to other services, including one psychologist, one social worker, four registered nurses, and two nursing assistants. These transfers reduced the annual cost of the substance abuse program by $250,000 to $300,000.