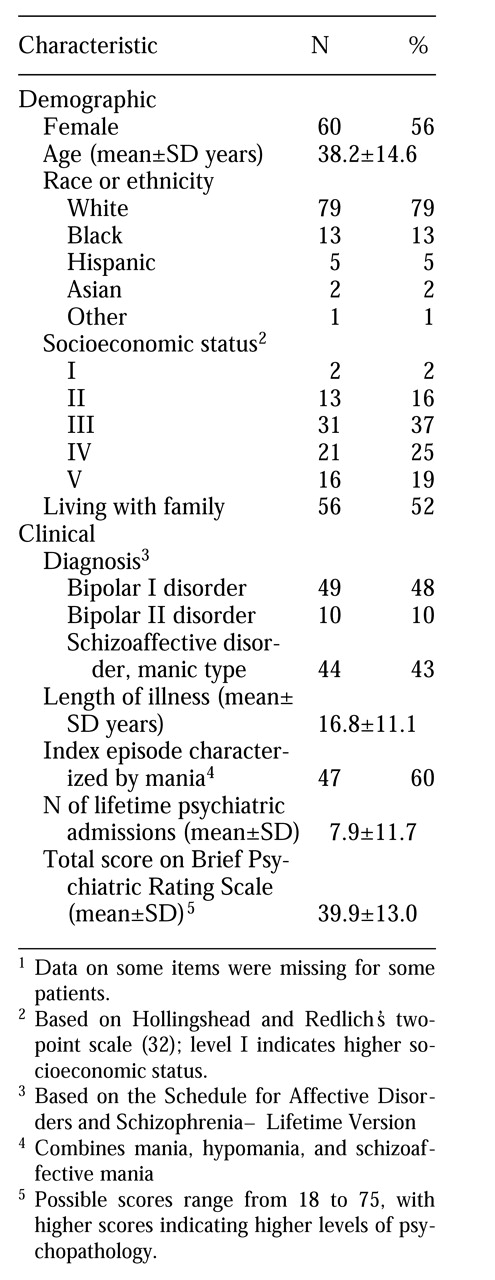

Predictors of time until rehospitalization

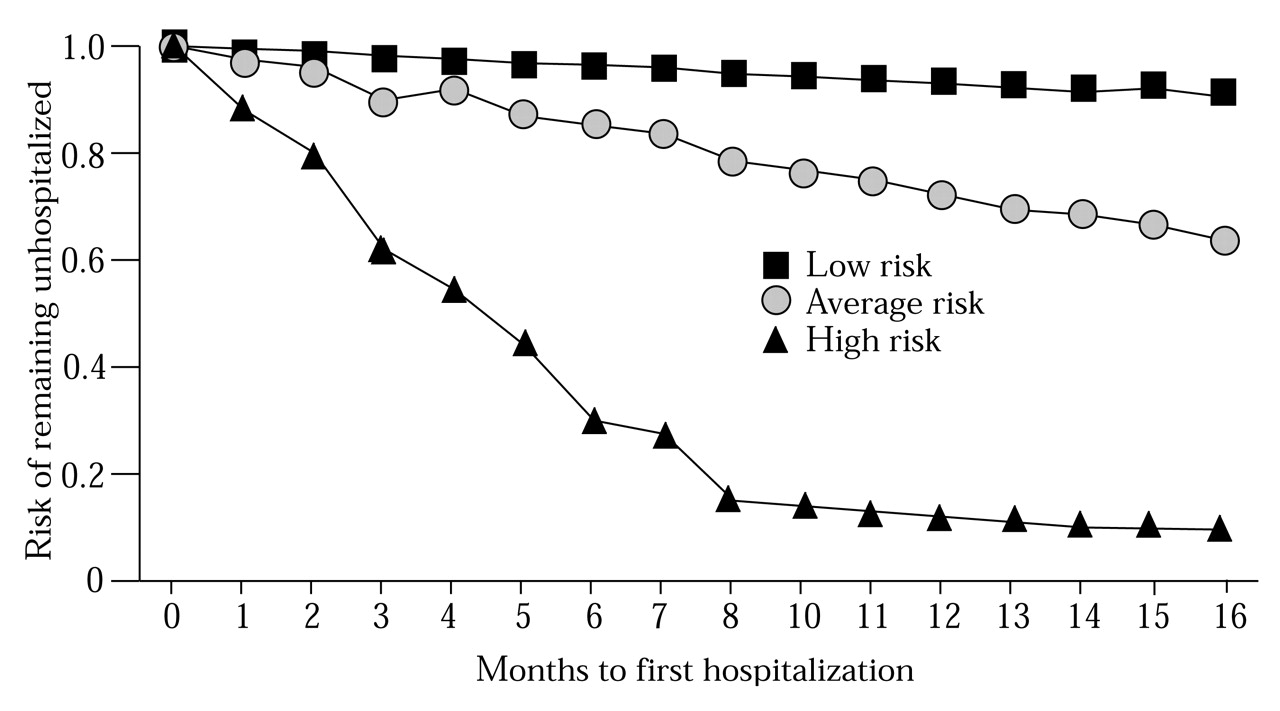

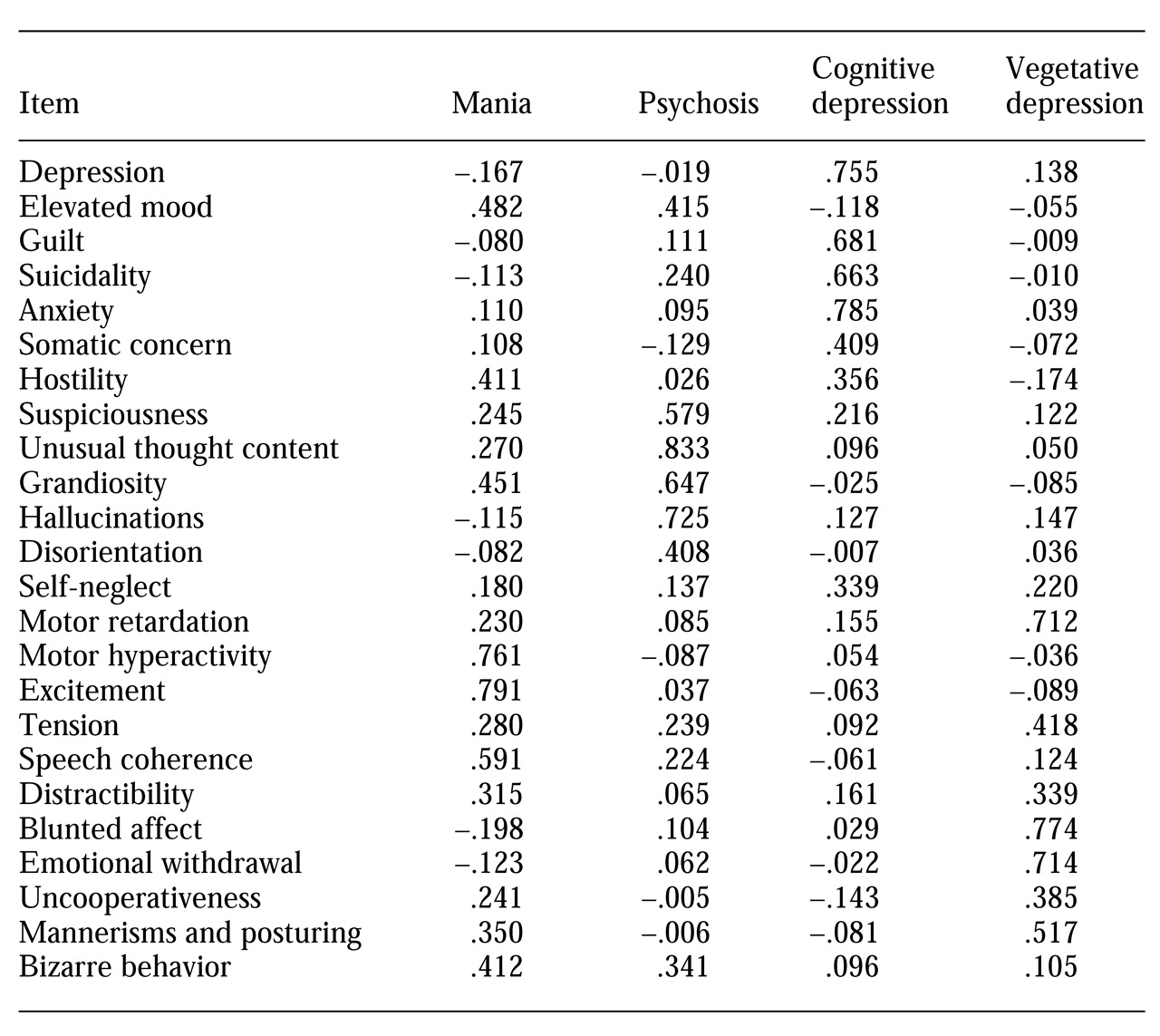

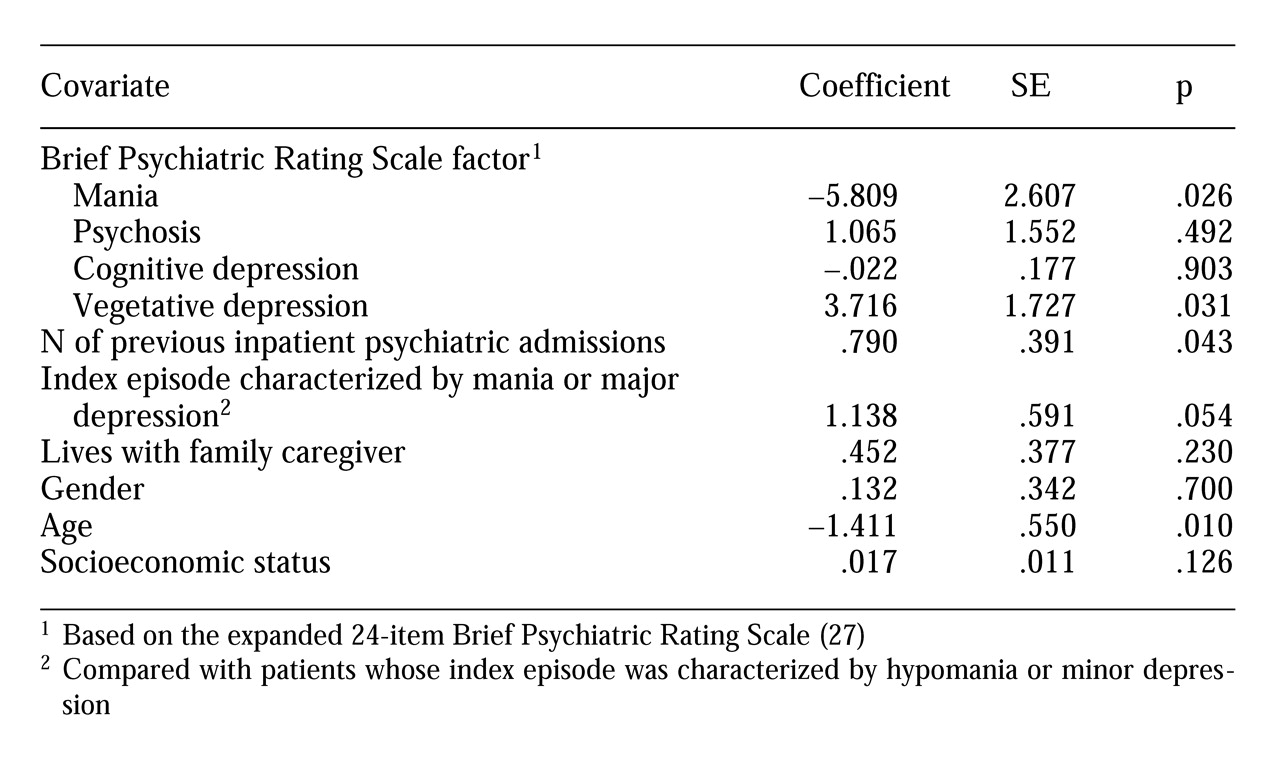

We hypothesized that the nature of symptom presentation at discharge would predict time until rehospitalization. The results of this study demonstrate that symptom profiles consistent with mania significantly decreased the likelihood of rehospitalization in the 15 months after discharge, whereas those consistent with a neurovegetative type of depression significantly increased the likelihood. By contrast, symptom profiles consistent with psychosis and a more cognitively characterized depression did not significantly alter the risk of rehospitalization during this time frame.

One possible explanation for these findings is simply that the BPRS mania factor is elevated primarily among patients with less severe forms of the illness (hypomania or bipolar II disorder), while the vegetative depression factor taps into a more severe form of the illness (schizoaffective disorder). However, the mania factor was not significantly associated with whether a patient's index episode was major (manic) or minor (hypomanic). Moreover, it was significantly, although modestly, associated with having a lifetime diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (r=.175, df=141, p=.036). Thus its protective effect is not likely to be explained by an association with a milder form of illness.

Similarly, because the vegetative depression factor was not significantly associated with a lifetime diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, the increased risk of rehospitalization among patients' scoring high on this factor does not appear to reflect the presence of the negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia. Although the vegetative depression factor was marginally and positively associated with having an index episode characterized by major depression (r=.160, df=141, p=.056), it was still significant in the multivariate analysis, which controlled for this association. Thus we do not believe that the predictive power of the mania factor and the vegetative depression factor can be explained as purely a function of their association with severity of illness.

It is of interest that in contrast to the BPRS symptom factors, the SADS-L variables—a lifetime diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder versus bipolar I or II disorder and the polarity of the index episode—were not significantly associated with time until rehospitalization. The relatively low predictive utility of the SADS-L variables may reflect the challenges posed by diagnostic classification in bipolar illness, which is complicated by the occurrence of mixed states as well as by problems in determining the presence of schizoaffective symptoms (

37,

38,

39). Our results from the BPRS factor analysis suggest that even within one pole—for example, the depressive pole—different subtypes exist that may further complicate, and potentially help refine, the prediction of outcomes such as rehospitalization.

In light of this complexity, scaling patients' symptoms along multiple dimensions—manic, depressive, and psychotic—may represent a more useful approach, at least to the prediction of rehospitalization. A logical extension of the findings reported here would be to use the symptom factor data in conjunction with cluster analytic methods to identify subgroups of patients at high and low risk for rehospitalization. Identification of such subgroups would enable clinicians to implement more strategic, symptom-targeted pharmacotherapies for patients with bipolar illness, such as the use of maintenance antidepressant medication or concomitant atypical neuroleptics. Identification of symptom subgroups of patients at high risk for rehospitalization might also provide a rationale for use of intensive outpatient treatment, such as day treatment, for more patients with bipolar illness or for use of multiple treatment modalities, such as combining family with individual or group treatment.

Based on a retrospective case analysis of 100 consecutive readmissions to a psychiatric inpatient unit, Talbott (

6) concluded that 40 readmissions might have been prevented by more intensive staff involvement with the patient or the patient's family. Although use of intensive outpatient mental health services is generally based on the overall severity of patients' illness, these data indicate that the presence of a neurovegetative depression may provide a better rationale for use of intensive treatment, because overall symptom severity as assessed by the BPRS total score was not significantly associated with time until rehospitalization. These data suggest that in the short term, patients presenting with a depressive episode characterized by prominent neurovegetative features should be treated more aggressively with both pharmacotherapy and intensive outpatient services to reduce the relatively high risk of rehospitalization that appears to be associated with this type of depression.

In contrast to previous investigations, our study did not find that female gender, lower socioeconomic status, or older age was significantly associated with increased risk of rehospitalization; in fact, in our study older age had a protective effect. These discrepancies are likely due partly to differences in patient samples, because the previous investigations mainly examined samples of patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia, in which, for example, the distribution of socioeconomic levels is more often skewed toward the lower end.

Interestingly, the association of age and time until rehospitalization, although positive at the bivariate level (r=.290, df=41, p=.057), was negative when the analysis controlled for the effects of illness chronicity (the number of previous psychiatric inpatient admissions) on age in the multivariate context (r=−.170, df=130, p=.052). Other studies reporting that the risk of rehospitalization increases with age have not uniformly partialled out the effects of chronicity of illness on the association between age and rehospitalization.

These findings raise additional research questions that cannot be answered within the limitations of the design of our study. First, information about the clinical course and treatment of the patients over the 15-month follow-up is needed to identify variables that may mediate or moderate the associations of the symptom factors with time until rehospitalization. For example, it is not clear whether the association of the vegetative depression factor with rehospitalization is mediated by an association of vegetative depression with relapse, or whether high scores on this factor may have defined a subgroup of patients who did not fully recover from their depressive index episode.

Incorporation into our model of such constructs as the adequacy of the prescribed pharmacotherapy, patients' treatment compliance, attitudes toward illness of patients' family members, and the help provided by patients' support networks may help explain the findings. For example, it is possible that the apparent protective effect of mania is related to the availability and use of more effective treatments for mania than for depression.

Second, although the expanded version of the BPRS (

28) has become a standard instrument in studies of treatment and outcome in bipolar affective disorder (

40,

41), its use here limits comparison of our findings with studies of unipolar affective disorder, for which the Hamilton Rating Scale (

42) is used almost exclusively. Research on unipolar depression has established that patients with different types of depression (mild or severe) respond differentially to the same treatment regimen (

43), and it would be useful to compare the two BPRS depression factors identified in this study with other, established classification schemas for depression.

A third research question raised by the findings is that the stability of the factor scores for individual patients must be evaluated over time to determine whether the BPRS factors are measuring trait- or state-dependent attributes. Because state- and trait-dependent types of depression may respond differentially to somatic and psychotherapeutic interventions (

44), this information has clinical relevance.

Fourth, the generalizability of the findings is limited to inpatients. In addition, although we found no significant differences in baseline demographic or clinical variables between the study sample and the patients who did not complete the 15 months of follow-up, the noncompleters may have differed in other respects not measured. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings in an outpatient sample, incorporate symptom measures specific to mania and depression, and examine treatment variables and intermediary outcome variables that may help explain the associations observed between symptoms at discharge from the hospital and the likelihood of rehospitalization over the next 15 months.