Several studies have pointed to an increased risk for depression among patients with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection. These patients reportedly have a higher prevalence of depression than persons who are HIV negative or who are HIV positive but asymptomatic (

1). Likewise, HIV symptomatology reportedly is associated with elevated measures of depression (

1,

2). A "dramatic rise" in depressive symptoms during the 18 months preceding an AIDS diagnosis has been reported (

3). Another study reported an increased risk of suicide among persons with AIDS (

4).

Depression is harmful to physical health as well. In one study, overall depression and "affective depression" were found to predict a more rapid decline in CD4 lymphocyte counts (

5). In another study, depressive affect was reportedly associated with increased mortality risk (

6). These findings indicate a need for effective treatments for depression for patients with AIDS and HIV infection, particularly those with more severe HIV disease.

Group cognitive-behavioral therapy, supportive group psychotherapy, and individual psychotherapies all have been reported to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression or distress among HIV-positive patients (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy was chosen for this project because it combines several features shown to be beneficial in this population. First, cognitive-behavioral therapy teaches coping strategies to reduce stress and alter thoughts that reinforce depression. Effective coping strategies have been shown to contribute to lower levels of depression among HIV-positive patients (

1).

Second, provision of social support through the group may be especially important for patients with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection who are often isolated from family members. Satisfaction with support systems has been shown to be inversely related to depression (

2). Third, the cognitive therapy approach in this project—a structured, time-limited, goal-directed intervention focused on current problems—is a treatment amenable for use in managed care settings as well as community mental health centers, where many patients with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection receive care.

This demonstration project was conducted to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, described by Beck and colleagues (

13,

14), plus adjunctive antidepressant medication for treating depression among gay men with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection.

Methods

Sample

Gay men with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection were recruited for the study through advertisements in a local paper serving the gay community in Washington, D.C. Each prospective enrollee underwent two clinical interviews, one by the project psychiatrist (the first author) and one by the project therapist (the second author). Subsequently, the psychiatrist and therapist derived a consensus DSM-IV diagnosis.

To be included in the study, patients had to meet criteria for major depressive disorder or dysthymia without active alcohol abuse or other drug abuse or dependence, acute suicidality, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, or psychotic disorder. Eligible patients were offered a course of cognitive-behavioral therapy and, if indicated, adjunctive antidepressant medication.

Fifteen patients—12 with major depressive disorder and three with dysthymia—were enrolled after providing informed consent. Twelve patients had AIDS (category C of the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) and three had symptomatic HIV infection (category B of the CDC criteria (

15).

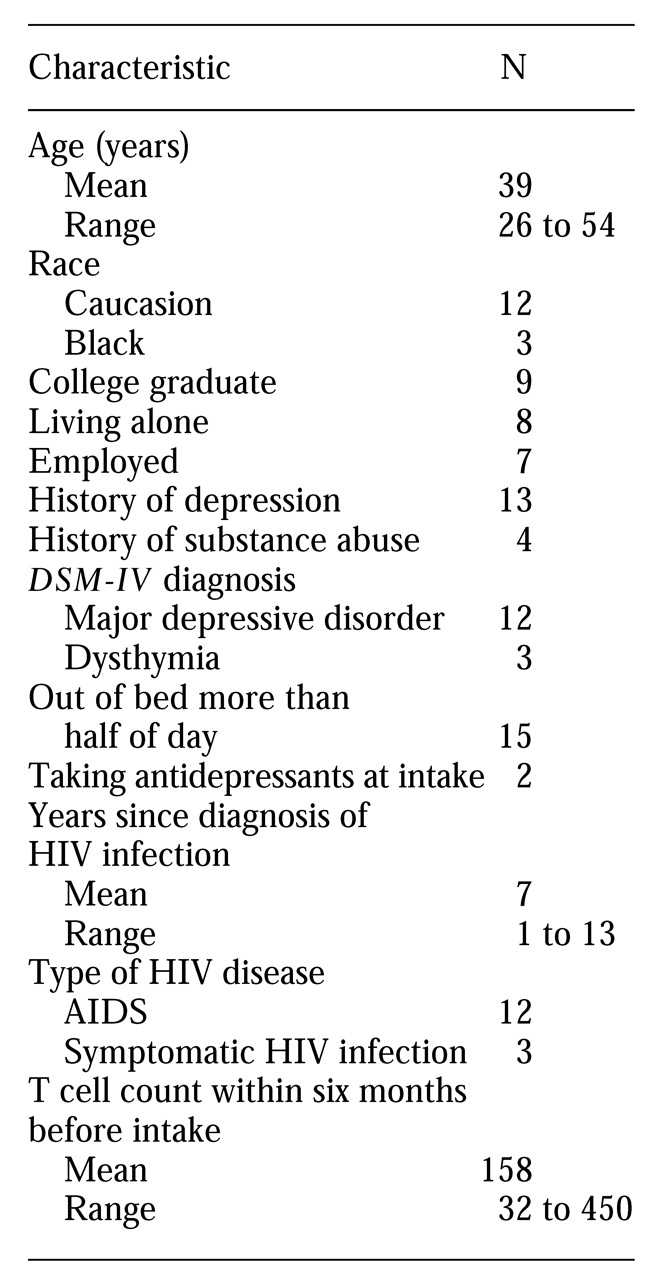

Table 1 shows other patient characteristics.

The observation period for each patient was 11 months, which included five months of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and a six-month follow-up period. During the follow-up period, the project therapist and psychiatrist met with each patient at intervals of six to eight weeks or as needed. Objective measures of depression and functioning—including the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (

16), the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (

17), and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (

18)—were used throughout the observation period.

Group cognitive-behavioral therapy

The cognitive-behavioral therapy was conducted by a licensed clinical social worker specializing in private-practice cognitive-behavioral therapy in the gay community. Two treatment groups were conducted, the first with nine patients and the second with six.

Some group cognitive-behavioral therapy procedures were adapted for the project population. In particular, the treatment duration was extended to 20 weekly two-hour sessions, to permit more intensive work on dysfunctional core beliefs and help prevent relapse. Patients were permitted to continue any ongoing individual or support group therapy and to start other individual or couples therapy, as needed.

The fundamental premise of the cognitive-behavioral therapy in this project was that teaching patients to recognize and challenge irrational perceptions and beliefs will enable them to interrupt depressive thought processes and relieve or prevent depressive symptoms. Several strategies specific to cognitive-behavioral therapy were used. Specifically, automatic thoughts were examined to illuminate their effect on mood and show how changing perceptions can avert depressive thoughts and symptoms. In addition, dysfunctional core beliefs about self-worth and expectations of others were examined to demonstrate how they contribute to vulnerability to depression. Specific instructions were used to modify dysfunctional core beliefs, and peer modeling and observational learning were used to enhance the therapy process.

At the beginning of the group therapy, each patient specified his therapy goals. Besides relief from depression, patients' goals also focused on work—job loss was associated with increased depression and lowered self-worth—and anxiety about family relations. Family relations generally were poor, largely due to prejudice about the patients' sexual orientation. Patients' goals also included issues of relationships or health. Substantial anxiety associated with health or relationship problems was common. During each session, the therapy goals served as an organizing point around which patients addressed problems and found solutions. The goals also were the basis for self-help experiments, designed in the group sessions and carried out in the intervening weeks.

The basic format for the cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions was as follows. At the beginning of each session, patients completed the BDI, and the results were reviewed by the therapist, with particular attention to suicidality. Each patient reported on the previous week's moods, thoughts, self-help experiments, and homework. Worksheets and instructions for self-help experiments focusing on skills or concepts of current interest were distributed.

This structured agenda occasionally had to be modified to give additional attention to a specific concern or crisis. Under these circumstances, the therapist would focus on the patient's particular difficulty, asking other group members to support and assist in the process. This tactic promoted empathy among the other group members and enabled them to collectively learn the skills taught to individual patients.

During the first ten sessions, the relationship between depression and automatic thoughts was examined using educational materials and the assignment of after-group exercises. Exercises included the completion of weekly worksheets about specific life situations to practice the skills of cognitive restructuring—identifying depressive triggers and associated automatic thoughts, finding the cognitive distortions in those thoughts, and developing realistic and productive responses. In addition, work was done on a behavioral level to illuminate the relationship between mood and activity. Because of this work, patients were able early on to participate in mood-improving pleasurable activities, with associated boosts in motivation and morale.

In the second ten weeks of therapy, relationships among dysfunctional core beliefs, automatic thoughts, depressed mood, and self-defeating behaviors were examined. Materials used in these sessions included handouts about the relationship between core beliefs and depression, questionnaires to identify patients' dysfunctional core beliefs, and worksheets for detailed examination of core beliefs, including how they originate, their advantages and disadvantages, and how to generate new core beliefs. (Sample therapy worksheets are available from the second author.)

Antidepressant medication

All psychopharmacological treatment was managed by the project psychiatrist, who met with each patient at six- to eight-week intervals to evaluate the need for antidepressant medication and, if indicated, to initiate or manage medication. The psychiatrist, with the patient's consent, had regular communication with the patient's medical doctor about symptoms and antidepressant medications.

Antidepressant medication was recommended by the psychiatrist if the patient had a sustained poor response to the group therapy or if the symptoms of depression significantly interfered with functioning. Two patients were taking an antidepresssant at enrollment; otherwise, patients generally were reluctant to start antidepressants, citing prior nonresponse, concerns about taking more medication, and fear of side effects. The frequency of severe side effects from antidepressant medications, particularly among patients with AIDS, has been reported to be as high as 25 percent (

19). The rate of dropout due to side effects within six weeks of initiating medication has been reported to be as high as 10 percent (

20).

Despite the initial reluctance, all of the seven patients offered antidepressants during the project eventually accepted medication. Thus a total of nine of 15 patients in the project received cognitive-behavioral therapy plus medication. The shift in attitude among these patients, which facilitated their acceptance of antidepressant medications, may have resulted partly from the group therapy, where information about medication was provided, fears about medications were discussed, and possible benefits of medications were explained. A variety of medications, including nortriptyline, paroxetine, and bupropion, were used, depending on symptomatology and on history of medication use and side effects.

All patients who accepted antidepressant medication responded with decreased symptoms and improved functioning. On average they remained on medication more than seven months (a range from one month to more than the 11 months of the study). Seven patients ultimately discontinued medication, two because they felt they were so improved that they no longer needed it and five because of side effects, including excessive sedation, liver function abnormalities, and gastrointestinal upset. Four of these five patients remained on medication at least two months (mean=ten months), a period well in excess of the periods of six weeks or less commonly used to define medication dropout (

20).

Results

Although the focus of this descriptive report is the adaptation of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and its feasibility for use with gay men with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection who are depressed, the patients' response bears some mention. The cognitive-behavioral therapy had a high retention rate: 13 of the 15 patients completed the course of therapy with good attendance (mean=15 sessions, with a range from eight to 20 sessions) and a high rate of compliance with the follow-up assessment. One of the 13 died shortly after the end of therapy and thus did not complete the outcome battery. Thus data were available for 12 patients at the end of therapy. Data were available for all of those patients at follow-up.

Outcome measures showed substantial reductions in symptoms of depression, with the mean HDRS score declining from 26 at intake (with a range from 8 to 38) to 9 after therapy (a range from 1 to 18), and 6 at the follow-up (a range from 0 to 13). An improvement of more than 50 percent in HDRS scores was experienced by eight of 12 patients from baseline to end of therapy and by all 12 patients from baseline to follow-up.

The mean BDI showed a parallel decline, from 24 at baseline (with a range from 8 to 38) to 15 at end of therapy (a range from 2 to 39) to 9 at follow-up (a range from 0 to 23). The BDI scores of four of 12 patients improved by 50 percent or more from baseline to the end of therapy, and scores of seven patients improved by 50 percent or more from baseline to follow-up.

GAS scores increased from 57 at baseline (a range from 40 to 70) to 72 at the end of therapy (a range from 60 to 90) to 80 at follow-up (a range from 65 to 90).

The limitations of this study must be considered in interpreting these results. The study was not controlled: the small sample may not be broadly representative, and the patients were permitted to use other therapies in addition to the cognitive-behavioral therapy. Thus the possibility that the patients' response was nonspecific or due to factors other than cognitive-behavioral therapy cannot be ruled out. Eleven patients used another therapy concurrent with cognitive-behavioral therapy: two used psychotherapy, five used medication, and four used psychotherapy plus medication. However, several patients had a history of nonresponse to such treatments. More important, several patients made comments about factors specific to cognitive-behavioral therapy that they believed had contributed to their improvement.

At follow-up, each patient was asked to describe the aspects of therapy most helpful to him. Several themes emerged in these self-reports. First, the therapy group provided social support for patients who previously felt isolated. Second, by observing comrades, patients learned that their problems were experienced by others, which decreased feelings of isolation and shame and allowed constructive interchanges about solutions or coping strategies. Third, the experience of empathy for others' distress contributed to a resurgence of self-esteem and was itself healing.

In addition, several patients reported that learning about cognitive restructuring had enabled them to focus on positive aspects of life, to use support and help from others more effectively, to recognize triggers for depression, and to develop internal skills to modify depressive thoughts. Their comments included "I'm glad to have learned the tools. I feel I know how to stop a lot of depression-causing or -deepening situations," "Group helped me train my mind to focus on good things," "[I] learned about distortions. I make sure I hear what the [other] person is saying, not just assuming," "Am able to see how my own thoughts influenced how I felt, that there was a lot more internal control than I thought," and "The cognitive therapy approach was helpful. I would be dead without it."

Supportive data pointing to specific mechanisms of cognitive-behavioral therapy's efficacy have recently been published. In a controlled study, Lutgendorf and associates (

11,

12) found that cognitive-behavioral therapy (plus relaxation training) was associated with significant improvement in cognitive coping skills among nondepressed HIV-positive subjects. The study also showed that improved cognitive coping skills were strongly related to decreased dysphoria, anxiety, and measures of total disturbance and mood disturbance.

Discussion

Among the patients in this project, the grim reality of their illness was a significant chronic stressor, which seemed to lower the patients' threshold for depressive responses to acute triggers. In other words, because of their physical illness, patients appeared chronically hypervulnerable to hopelessness, helplessness, and self-blame associated with a variety of stimuli. These circumstances created obstacles to the core work of the cognitive-behavioral therapy—the explicit and direct challenge of automatic thoughts and dysfunctional core beliefs—and made the cognitive-behavioral therapy more arduous and prolonged.

In addition, although the patients in the study generally could use behavioral techniques to improve mood, some resisted working on cognitive distortions and core beliefs, based on the attitude of "Why bother? I'm going to get sicker and die; it's no use." This resistence to cognitive restructuring was particularly unfortunate, because, as noted by Lutgendorf and associates (

12), coping strategies that facilitate the acceptance and integration of life changes that are associated with symptomatic HIV infection and AIDS may be a vital resource for this population. The most seriously physically ill patients in our project seemed at greatest risk for a relapse into depression. And, as previously noted, hopelessness and depression, in turn, may actually exacerbate physical decline (

5,

6). For all of these reasons, treatment-resistant patients may very well be the ones most in need of the remedial and preventive effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

In contrast to the findings of this project, some studies have failed to show an advantage of cognitive-behavioral therapy over other treatment modalities for patients with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection. Among the reasons for these findings may be the low pretreatment depression scores in some studies, which may have created a "floor effect" and left little room for improvement (

8,

9). Another factor may be the short duration of treatment in some studies, such as eight sessions (

7). Our experience indicates that an adequate trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for depressed patients with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection should be considerably longer. A remaining question is whether a longer treatment period or a series of booster sessions might be even more effective for promoting cognitive restructuring and preventing relapse.

Concerning the therapy content, several themes emerged that underscored the complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors associated with AIDS and symptomatic HIV infection. Besides generalized guilt— "Look how I screwed up my life"—themes included guilt about contracting HIV, AIDS as a punishment for being gay, and guilt about the possibility of infecting others. Anger—toward the medical community, lovers, or the therapist—was common and often seemed disproportionate to the supposed stimulus. The appearance of new symptoms of physical illness was often associated with a relapse into depression, including cognitive distortions like "My life is no good anymore; there is no value in life." Within the group, one member's becoming more ill often triggered hopelessness and fear among others.

The patients also expressed a sense of having lost value to others— "I am no longer attractive"—which interfered with the formation of new relationships, especially with other HIV-positive people: "What's the use? They're going to die too." Last, group members frequently focused on philosophy-of-living issues rarely mentioned in other depression treatment groups, such as "What do I want to do with my life?" and "How is life to be lived, as long as possible or as fully as possible?" These questions frequently took on imminent importance. It was often the sickest members who posed these questions; in so doing, they allowed others to talk about their own fears of the future.

Concerns about dying were common, especially in the first therapy group. One patient deteriorated during the second half of the group's sessions, dying shortly thereafter. The availability of protease inhibitors and the hope for increased survival became known during the later weeks of the second therapy group. With this new possibility for treatment, patients' underlying assumptions about the inevitability of death shifted. The resulting hopefulness seemed to allow these patients to focus more constructively on their treatment.

The therapist's qualities also were important to the treatment's effects. Patients' reports pointed to the therapist as a vital element in the group's success. During the cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, the therapist was an active instructor, coach, and facilitator. He was also available to patients for crisis management between therapy sessions. Personal qualities were especially important, as reflected in these patients' reports of what was most helpful: "The therapist was accepting and understanding and willing to learn what it means to be HIV positive so that I felt he was genuinely supportive and cared—he is the best I've seen or had the pleasure of talking with," "[He] is gentle and non-confrontational," and "I trusted [him]."

Conclusions

The structured group cognitive-behavioral therapy in this project was attractive to most patients. Follow-up reports indicated that the intervention's emphasis on cognitive restructuring was particularly helpful in enabling patients to cope with and prevent the recurrence of depression. We believe that the approach combining modified group cognitive-behavioral therapy and adjunctive medication that was used in this project may be practical and useful for treating patients with AIDS or symptomatic HIV infection who are depressed, particularly in managed care and mental health center settings, and is worthy of further study.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by a bequest from the estate of Paul Garofalo of San Francisco.