The American Psychiatric Association announced in November 1949 that under a grant from the Commonwealth Fund, it was launching a Mental Hospital Service that would include a monthly mental hospital news bulletin. The publication, initially called the A.P.A. Mental Hospital Service Bulletin, was first published in January 1950. Its name changed as of the seventh issue of volume 2 to Mental Hospitals. In January 1966 it was renamed Hospital and Community Psychiatry, and in January 1995, at volume 46, its name was changed to Psychiatric Services.

The year 2000 is the 50th anniversary of the journal and an opportune time, as Ginzberg notes, to reflect on our past so that it may better inform our future. This paper uses the 50 years of this journal's publication to examine the history of the last half-century of psychiatric services in the United States. For convenience, when the journal is cited in any general way, it will be referred to as Psychiatric Services.

Background

When considering the contents of this paper, three basic issues arose. The first was how to keep the paper focused, which requires acknowledging that much in a 50-year history of psychiatric services could not be covered. The paper is largely organized around the locus of psychiatric care and treatment during the last half-century. This point of view was chosen because the location of treatment has been the battleground for the overarching ideology of care and treatment, and hence the nidus for the crystallization of policy and legal reform, for 50 years.

The debate, of course, has been about institutional care and treatment versus community care and treatment. This focus has been soundly criticized (

2,

3), and rightly so. It has distracted us from appropriately examining the adequacy, quality, individualization, and respectfulness of psychiatric care and treatment. Nonetheless, it is the history of psychiatric services during the second half of the 20th century.

Staying fixed on a focus that can be contained within an article means that many topics are not addressed. Because this is a paper on psychiatric

services, most psychopharmacology advances are not included. Also not covered in the paper, although they have received ongoing coverage in the journal, are children and adolescents (

4), the geriatric population (

5), and women (

6) as well as more discrete subpopulations such as mentally ill mothers (

7,

8), young adult chronic patients (

9), persons with both mental illness and substance abuse (

10), and recipients of psychiatric services who speak out about them (

11).

The second issue that arose is that in discussing psychiatric services, we don't know what we're talking about. I don't mean that pejoratively, but literally. We use terms that fail a basic test of communication: that people know what you mean when you use them.

The buzzwords of the last 50 years of psychiatric services are undefined, ill defined, or differently defined by each person who uses them to meet his or her needs. Terms that fall under the penumbra of ambiguity, and have been so identified in the pages of

Psychiatric Services, include these ten examples: "deinstitutionalization" (

12,

13), "community" (

12,

13,

14), "chronic mental illness" (

13,

15), "case management" (

16,

17,

18), "empowerment" (

19,

20), "recovery" (

2), "service system" (

21), "advocacy" (

22), "patient-client-consumer" (

23,

24), and "least restrictive alternative" (

12,

25). I can hardly create a new language for this paper, so I will use the jargon we have all come to employ and do my best to make it clear.

The third issue was how to deal with "deinstitutionalization." Variously called a "policy," a "concept," a "movement," a "protest movement" (

26), even an "era," deinstitutionalization is probably best labeled a "factoid." Basically, deinstitutionalization wasn't. That is, it wasn't preconceived, and it probably never happened.

The depopulation of America's state hospitals occurred because of a confluence of several factors: resource-poor state hospitals at the end of World War II; the belief that treatment closer to relatives and community jobs was better than isolated, segregated treatment; the first psychopharmacologic revolution, with chlorpromazine; empowerment of legal advocacy and an activist judiciary; and—perhaps most important—the ability of states to shift costs to the federal government through Medicaid, Medicare, Supplemental Security Income, and federal grants (

27,

28).

There may be no better evidence that the process of moving patients out of state hospitals started considerably before any designation of the process as "deinstitutionalization" than that between 1954 and 1976, the census of public psychiatric hospitals decreased by 70 percent (a point to be discussed later in this paper), while the term "deinstitutionalization" did not appear in the index of

Hospital and Community Psychiatry until 1975. It did not appear in the title of a paper in this journal until 1976 (

29).

What actually did take place was labeled by Talbott (

27) at the end of the 1970s as "transinstitutionalization." He described it as "the chronic mentally ill patient had his locus of living and care transferred from a single lousy institution to multiple wretched ones." In the 1990s many state hospitals are far better than "lousy," many nonhospital living arrangements are far better than "wretched," and some of both kinds of facilities can be excellent. However, the quality of the place one resides in is distinct from who does or does not call it an "institution" and therefore has little to do with "deinstitutionalization."

Having attended to these three issues, I will look at the development of psychiatric services over the last 50 years under the headings of "dehospitalization," community care and treatment, economics, empowerment, and interface issues. As a background for what was accomplished by those directly involved in developing and implementing psychiatric services during this past half-century, it is helpful to be aware of what the federal government and the courts were doing that shaped these developments.

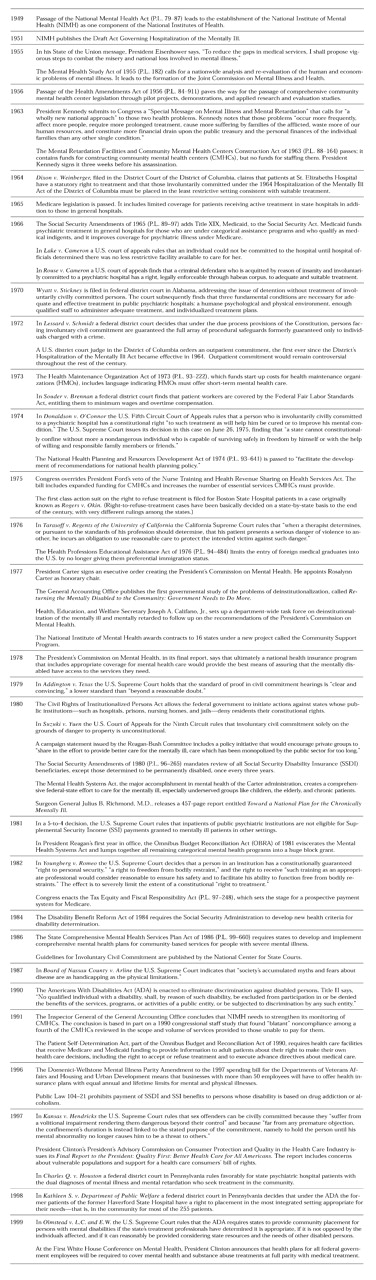

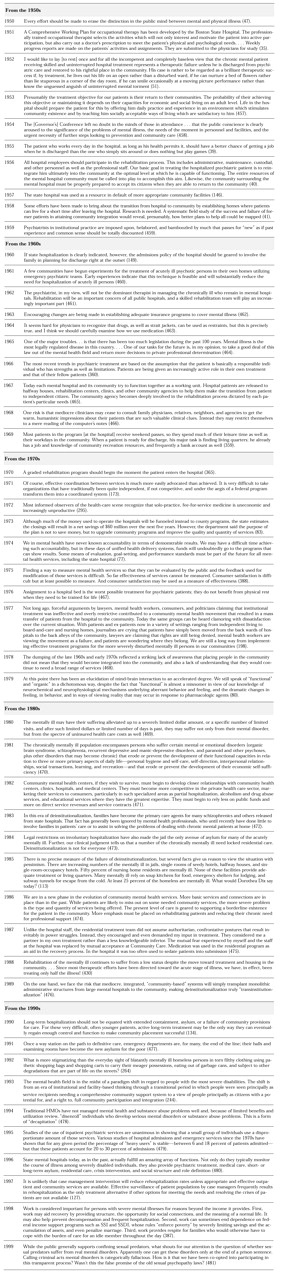

Table 1 provides this information; the sources for it are mostly the journal's News and Notes section and the Law and Psychiatry column edited by Paul Appelbaum, M.D. In most cases it is not clear whether the government and the courts were leading or were following public or professional sentiment. However, in all cases the government's and the courts' efforts have been fundamental to the changes that ensued.

Dehospitalization

Because the term deinstitutionalization seems to be inappropriate for the movement of persons in state hospitals out of them, the term "dehospitalization" is employed here. The term has been used in

Psychiatric Services (

30), although rarely. Its use predates the use of "deinstitutionalization," and it seems more accurate for describing a phenomenon of transferring patients out of state hospitals because it implies no judgment about whether where they went could be considered an institution (

14).

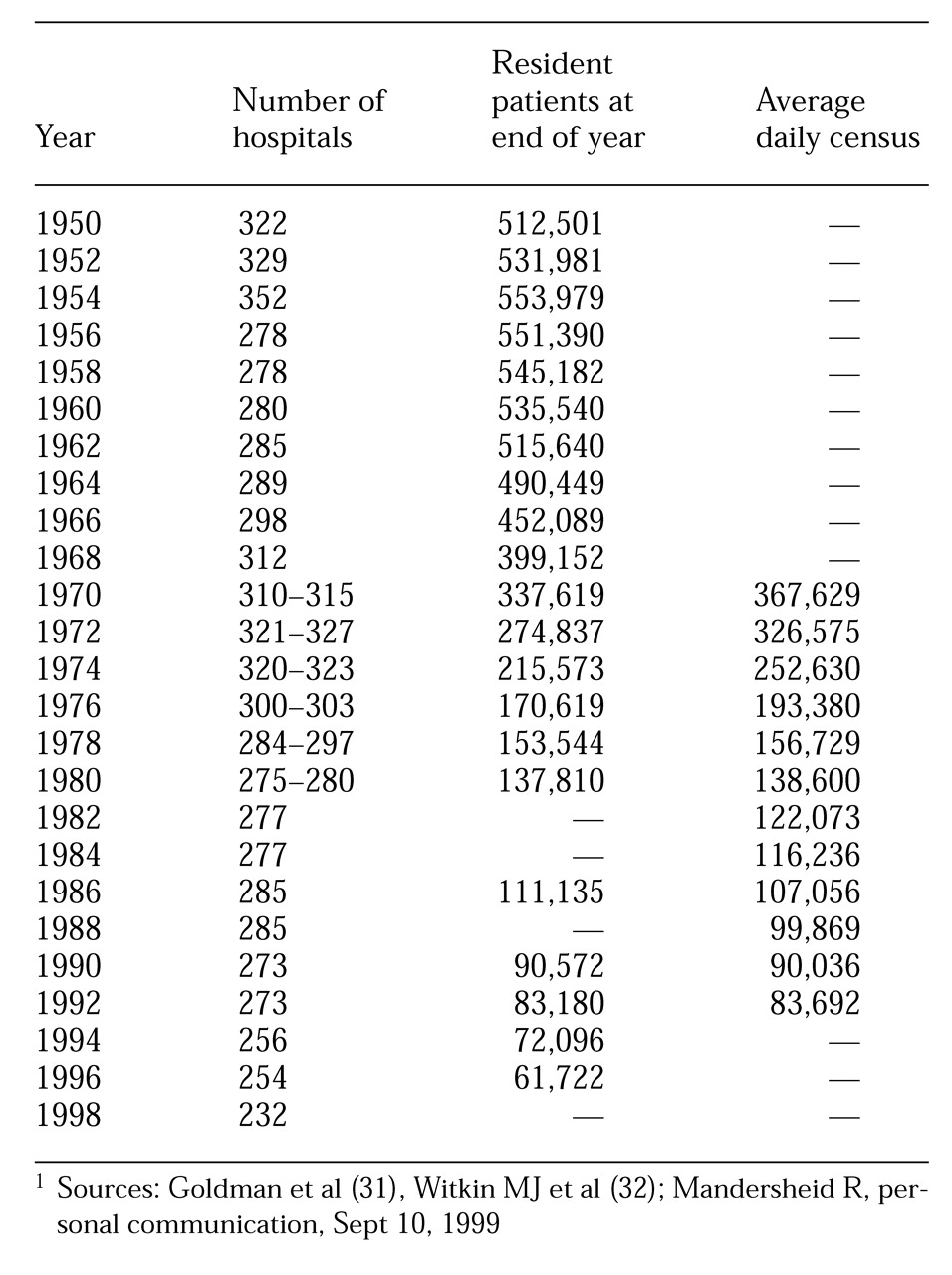

That the last 50 years was really an era of dehospitalization can be gleaned from

Table 2, showing data for state and county hospitals from 1950 through 1998 (

31,

32; Manderscheid R, personal communication, Sept 10, 1999). As the table shows, the decrease from the highest number of hospitals, in 1954, to the lowest number, in 1998, was 34 percent, whereas the year-end census of patients between 1954 and 1996 decreased by 89 percent.

Much of this decrease in the size of state hospitals is attributable to shortening lengths of stay. For example, between 1971 and 1975, there was a 41 percent decline in length of stay (excluding deaths), or a decrease in the median length of stay from 44 days to 26 days (

33). For all the attention that the closing of state hospitals has received, it has really been the movement of patients out of each of the state hospitals and each hospital's progressive decrease in size that account for the lowered national state and county hospital census.

In 1991, discussing his tenure as an attendant at Worcester (Mass.) State Hospital in the early 1950s, Vogel (

34) indicated that he was personally responsible for 55 patients, the licensed nurse oversaw the care of 700 patients, and the physician was seldom seen except to certify deaths. Patients' freedom of movement was unpredictable as "patients were sometimes put into physical restraints because staff objected to their habit of masturbation, wandering, or simply getting into things." Patients were given work assignments because "the hospital virtually would have ceased to function had it not been for its unpaid workers." Vogel's comments conjure up images of what people think of as all aspects of all state hospitals of the late 1940s and 1950s—"snake pits."

Vogel's memoir is without doubt true, and it was not published until fairly recently because few publications of the earlier era were exposing the condition of state hospitals. (Exceptions were Mary Jane Ward's

The Snake Pit, published in 1946, and Albert Deutsch's

The Shame of the States, in 1948.) However, some rather surprisingly positive movements were also occurring. Most prominent among them is what we would now label psychosocial and vocational rehabilitation. Throughout the 1950s scores of examples of state hospital programs articulated the principles that the focus of the state hospital was to prepare patients to live in the community, that work and social skills were essential components of successful community living, and that it was the hospital's task to

teach patients these skills (

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43).

Not only were social skills and vocational training recognized as important, but it was also recognized that effective interventions in these areas required a multidisciplinary effort (

41,

44). Further, personnel were aware of the risks of prolonged stays in state institutions, a condition called by some "institutionalitis" (

45). And all these efforts were made in acknowledgment that not the hospital—but rather the community—was the focus: "As we come to accept the circumstances of hospitalization as just one aspect of treatment, and possibly not an essential phase at that, there is an increasing preoccupation with those aspects of illness as displayed in the community" (

41).

During this era, overcrowding and underfunding were rampant (

46,

47,

48), standards were low to nonexistent

46,

47,

49,

50,

51,

52), and the rehabilitation effort could not be sustained. The 1960s was a decade during which the leaders of state hospitals were busy redefining the role and designing the functioning of state hospitals to ensure the hospitals' future existence (

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62). Other issues that were being considered during this era were state hospital habituation ("institutionalism") (

63,

64), the sufficiency of no more than symptomatic relief (

65), families' and patients' resistance to discharge (

66,

67), and the development of adequate community programs to effectively maintain individuals with chronic mental illness outside state hospitals (

68,

69,

70,

71).

The 1970s can be best characterized by a mid-century statement that "hospital-busters and hospital-preservers agree on only one point—there is no single universally applicable solution to the problem" (

72). It was in this period that the real debate about closing or retaining state hospitals emerged (

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81), and some state hospitals were actually closed (

82,

83,

84). While the political debate raged, state hospitals began to become more integrated into community services, largely through unitization—that is, geographic matching of state hospital wards and catchment areas (

85,

86,

87).

As components of this transition, prospective patients began to be denied admission with a new vigor (

88,

89), outcome data began to be examined (

90,

91,

92,

93), and even purchase of service contracts with state hospitals was proposed (

94). Perhaps the best summary statement about state hospitals during the 1970s is that of Maxwell Jones (

95): "I'm very worried about state hospitals, which I visit in many parts of the country. They are all demoralized and feel forgotten. The interest (and money) has moved to the new community programs, which are not supplying the answer to chronic mental patients."

Of the last five decades, the decade of the 1980s was the least innovative as far as state hospitals were concerned. The issues of the 1970s continued to be prominent: the role of the state hospital (

21,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101), including whether more state hospitals should be closed (

102) or if in fact any were necessary (

103); efforts to reduce state hospital admissions (

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109); and further refinements of state hospital organization and management (

110). Perhaps the one new debate—or at least it was formulated more explicitly—was the controversy on the pros and cons of "deinstitutionalization" (

111,

112,

113,

114).

Issues surrounding psychiatric services in state hospitals in the 1990s were basically more sophisticated examinations of the issues developed in the 1970s and somewhat refined in the 1980s. The psychiatric profession was focused on how the population that uses state hospitals was changing (

115,

116,

117,

118,

119); who kept returning despite the improvement of community services—that is, the examination of "recidivism" (

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128); and the need for asylum for certain patients (

129,

130). A continuing argument was that on the one hand we had more patients in state hospitals than needed to be there (

131,

132), and on the other that many with chronic mental illnesses needed long-term inpatient treatment (

133,

134,

135).

Strong criticisms of the role of the state hospital also erupted in the 1990s. The 30-year debate on this role has been driven more by ideology than by patient care needs (

136,

137). Shame on us all.

Community care and treatment

In the early 1950s, Daniel Blain (

138), then the medical director of APA, was already explaining the change in emphasis from hospital to community-based care: "The emphasis upon out-patient services, home treatment, day hospitals, and the like grows out of the recent advances in psychiatry which have made possible much care and treatment without hospitalization." The foundations for many of the "innovations" of the 1960s through the 1990s were actually rooted in the 1950s. The programs were not widespread in the 1950s, but they were emerging, and they were felt worthy of discussion in the literature.

As the state hospitals in the 1950s were preparing to discharge patients who did not need hospital-level care, what were community-based professionals doing? Interventions that began to blossom in the 1950s included general hospital psychiatric units (

139,

140); outpatient clinics (

140,

141); halfway houses (

142,

143,

144); day hospitals (

140,

145); social clubs for "ex-patients" (

138,

146); family care (

146); antistigma interventions (

141,

144,

146); preventive services (

138); and the use of visiting professional teams to go into patients' homes (

138), private doctors' offices, (

147) or remote rural areas (

148).

While model service delivery methods were being developed, earlier treatment methods such as hydrotherapy (

139), and earlier problems such as staff shortages—for example, two social workers for 3,200 patients (

142)—simply moved into the new loci of care and treatment.

The 1960s might well be characterized by an axiom recounted in 1960: "The patient is better off in the community, and the hospital is better off without the patient" (

149). By the early 1960s principles of community treatment were well articulated (

150). First, whenever possible, a patient should remain in his or her home community and be treated there. Second, hospitalization, if required, should be short, with a rapid return to outpatient services. Third, early intervention should be available to avoid the need for hospitalization whenever possible. And finally, programs offering alternatives to hospitalization should be fostered, as they will be less expensive and more therapeutic.

By the mid-1960s the mental health professions had a good understanding of what comprehensive treatment in the community meant: "Comprehensive community psychiatry refers to an array of therapeutic and supportive programs designed to meet the needs of all patients and to meet the needs of a single patient at different times during the course of his illness" (

151). At the same time came the early recognition that the public and private sectors were beginning to blur: "The rise of community psychiatry is creating a closer relationship between public and private agencies and institutions and, to some extent, is diminishing their functional differences" (

152).

The 1960s saw refinements of many of the interventions of the 1950s, such as general hospital psychiatric units (

153), day hospitals (

154,

155,

156), night hospitals (

154,

155), halfway houses (

157,

158), social rehabilitation and employment (

159,

160,

161,

162), and outpatient clinics (

163,

164,

165). New interests in the 1960s, or those that began to receive more attention, included emergency services programs (

150,

166), services to police departments (

167,

168) and correctional facilities (

167), hospital readmissions (

163), adequate housing (

159), the employment of former patients in human services (

169), and the integration of services across organizations (

170,

171).

Two interesting points of debate that would hound mental health professionals throughout the remainder of the century were clearly set out in this era. The first focused on the issue of the permanence of community-based services and the accompanying demise of state hospitals. Thus Greco (

166) wrote in 1961, "Any reversal of the present-day trend toward keeping patients out of the hospital as long as possible, and discharging those admitted at an early date, seems unlikely," while Ewalt (

167) said in a keynote address that same year, "The state hospital has been investigated, inspected, reorganized, converted, divided, dispersed, and even abolished, in fact or in theory, by countless imaginative persons motivated by a variety of urges. The state hospital survives, however, and is an amazingly tough and resilient social institution."

The second long-lasting issue was the dynamic tension between autonomy and dependency in relationship to services provided to those with chronic mental illness. Drubin (

154) wrote in 1960: "Again we cannot help but ponder whether or not we might be developing a tendency to provide too many crutches or even stumbling blocks rather than stepping stones to final discharge from the hospital by referring more patients than necessary to the day-hospital, night-hospital, foster home, cottage plan, half-way house, member-employment program, or patients' discharge quarters."

An early statement of the 1970s was Hirschowitz' view (

172) that "many programs have demonstrated that biopsychosocial principles can be practiced and applied to the management and rehabilitation of psychiatric casualties." Two other propositions that would become foci of discussion for the next 30 years were set forth by Feldman (

173) early in the 1970s. First was the dilemma of a two-class system of care: "As we have learned to our great misfortune in this country, services offered only to the poor quickly become poor services." The other was the matter of the involvement of recipients of services in the development of those services: "Responsiveness simply means that people who receive mental health services must have something to say about the nature of those services and the way in which they are provided. We are clearly in an age of consumer rebellion, and mental health services should be no less a target than automobiles, industrial pollution, or phosphate detergents" (

173).

The 1970s witnessed further development, and new evaluation, of service interventions established in the preceding two decades. Among them were residential facilities (

174,

175,

176,

177,

178,

179), employment programs (

180,

181), traveling teams of professionals (

173,

182), and programs to address readmissions (

183,

184,

185,

186). New concerns were expressed about hospital admission rates (

181,

187,

188), and programs were developed to provide acute psychiatric treatment in nonhospital settings (

181,

189). Evaluation studies of services began to be undertaken (

190,

191,

192), and an early attempt at utilization review was made (

193). Two issues that would haunt the provision of psychiatric services to the end of the century emerged in this decade: the application of the principle of the least restrictive alternative in psychiatric services (

181) and the burden of restrictive formularies (

182).

Two new forms of services were born during the 1970s. One became known as case management. In the 1970s there were two descriptions of providers that would certainly be called case managers today; they were known as "brokers" in one service system (

194) and "continuity agents" in another (

195).

The second new kind of service was what is now called assertive community treatment. Drawing on principles intermittently articulated throughout the previous 20 years, Stein and Test created a program to help individuals with chronic mental illness sustain community life that would be as free of inpatient treatment as possible, prevent the development of the chronic patient role, maximize community adjustment, improve self-esteem, and enhance quality of life (

196,

197). Test and Stein (

198) articulated two guiding principles that could be the clarion call for the rest of the century for the nature of psychiatric services for those with chronic mental illness: "A special support system should be adequate to assure that the person's unmet needs are met" and "A special support system should not meet needs the person is able to meet himself."

The 1970s were characterized by surprises about and criticism of the ideology of the transfer of care that was driving clinical services. In one catchment area of San Antonio (Tex.) State Hospital, the establishment of a community mental health center actually increased rather than decreased state hospital admissions (

188). Maxwell Jones (

192) was highly critical. He indicated, "I am unaware of any state that was circumspect enough to request adequate information before supporting this movement of chronic mental patients from the state hospital to the community. The political and economic pressure to lessen the tax burden by lowering the hospital census has been too strong." Further, he remarked, "It seems to me that the tendency to use nursing and boarding homes cannot be equated with health planning, but rather lack of it."

One of the last comments of the 1970s about community care, published in the December 1979 issue, provided one administrator's startling epiphany: "Patients often do not see life in the community as more desirable than life in the institution; if they did, they would leave the institution" (

199). Really?

The message of the 1980s was that community services needed to be significantly improved to meet the needs of those who were in the community as the result of dehospitalization. "Planners, leaders in psychiatry, and government officials simply cannot be allowed to proceed with deinstitutionalization in the absence of adequate community programs—at the very time when new, young chronic patients are emerging in unprecedented numbers," said Talbott (

200).

Better-planned and further-developed services were promoted or initiated in the areas of needs assessment (

201,

202); aftercare specialty services (

203,

204,

205,

206,

207); case management (

16,

18,

208,

209); residential care, including quarterway houses (

210,

211,

212), three-quarter-way houses (

213), board-and-care homes (

214), and boarding homes (

215); community mental health centers (

216,

217); continuity of care (

218,

219); asylum care (

220) and autonomy (

221); family care (

222); and crisis care (

223,

224). There was a renewed focus on evaluation research, including prediction, outcome, and effectiveness studies, on such topics as adjustment to community living (

225), hospital admission rates (

226,

227), effects of case management (

228,

229), quality of life (

230), treatment compliance (

231), and intensive residential treatment (

232).

A population that emerged as of particular interest, and one that would remain of significant concern during the next two decades, was the homeless mentally ill. The situation was described in 1983 as follows: "The homeless have become a major urban crisis. The streets, the train and bus stations, and the shelters of the city have become the state hospital of yesterday" (

233).

In community care, the 1980s was a decade of consolidating practices, evaluating efforts, and facing new problems. It was more of a decade of tinkering than it was of innovating.

The 1990s might best be characterized by an insight in a Taking Issue column by Lamb (

234): "Ideology should not determine clinical practice, but rather clinical experience should determine ideology." An example of ideology determining practice was revealed in Geller's evaluation (

235) of a crisis service's mission to divert admissions from the state hospital with the expectation (or even "knowledge") that it would produce treatment closer to individuals' homes and in the "least restrictive setting." The outcome did not support the ideology; patients were often hospitalized at a location across the state to avoid admitting them to the state hospital, which was much closer to their neighborhood.

The last decade of the century included extensive evaluation of what psychiatric services had and had not accomplished under the umbrella of community services. Services scrutinized included case management (

236,

237,

238,

239,

240), residential programs (

241,

242,

243,

244,

245,

246), partial hospitalization programs (

247,

248,

249), admission diversion interventions (

235,

250), and attempts to address noncompliance (

251,

252).

One service type of particular interest was continuous treatment teams, most commonly labeled assertive community treatment, or ACT (

253,

254,

255,

256,

257,

258,

259). Although assertive community treatment was reported in many demonstration projects as a successful intervention on many outcome variables, an unsettled debate remains about ACT's place in the overall service system. McGrew and colleagues (

258) decided it was time for "wide-scale dissemination of assertive community treatment as an effective form of community care for persons with serious mental illness." Burns and Santos (

256), in a review article, concluded that studies to date did not answer the question "of the place of assertive community treatment in a system of care."

Two populations of particular interest during the decade of the 1990s were the homeless mentally ill (

260,

261,

262,

263,

264,

265,

266,

267) and hospital repeat users or recidivists (

238,

268,

269,

270). One of the more poignant articles about homelessness, one that helps in distinguishing between ideology and reality, was the description of shelter life by Grunberg and Eagle (

260). How different is the Fort Washington Men's Shelter in New York City, as they portray it, from state hospitals at their worst in the "predeinstitutionalization era"? "The residents sleep in cots on the armory drill floor. No walls separate them from each other or from the public view…. The windows are poorly lit, and walls are streaked with dirt. Various corners are damp with urine…. Doors are missing from bathrooms…. The beds are lined up in rows of approximately 20 beds wide and 50 beds long, with usually only one or two feet between them…. Approximately one-fourth of the residents choose to spend their day inside the shelter and may not leave the building for days or weeks at a time."

In order to move us away from ideologically determined to clinically rooted policy, principles of care and treatment were promulgated, including those by Bachrach (

271) and Munetz and colleagues (

272). The basic components of these principles were that mental illness is a biologic disorder, with its expression influenced by genetic, personal, and environmental factors; the person is not the illness, and the illness is not the person; services must follow assessment, must be individualized, and must be modified as needed; treatment must be as aggressive as warranted, while respecting whatever degree of autonomy the recipient of services is capable of; treatment needs to be culturally informed and involve family members and significant others; recipients of services need to be involved in the planning of those services to whatever degree they are capable of; and outcomes of services must be realistic, researchable, and researched.

Where are we now? One conclusion is that in someplace approaching nirvana, the state hospital can be completely replaced by a community-based system of care and treatment. Thus Okin (

273) concluded about western Massachusetts, "With a clear vision, concerted political will, a supportive constituency, a powerful catalyst (in this case, a judicially enforced consent decree), sufficient resources, and careful targeting of these resources to specific services designed to serve patients with severe and persistent mental illness, it is possible to develop a system of care in the community that can substantially and responsibly reduce, or totally eliminate, the need for state hospital treatment."

Even if this is so, are persons with chronic mental illness then "deinstitutionalized"? Robey (

245) found that, to some extent, supervised living arrangements typically provided by community residential and transitional housing agencies are likely to represent for the residents an institutional or semi-institutional environment. And Lamb (

274) reported on a "95-bed locked community facility," one of 40 such facilities in California. By what stretch of the imagination are secure facilities of 100 (more or less) inhabitants, also known as patients or inmates, providing "life in the community"?

All too often, psychiatric services continue to be built on wishes for outcomes rather than on data (

250). And we remain trapped between the dialectic of the legalistic goal of minimizing restrictions on liberty and the clinical goal of maximizing clinical outcomes through optimal treatment interventions (

272).

Economics

In every decade of the last five, questions about who would pay for care and treatment were raised. In no decade did there appear to be any widespread endorsement of a major intervention that will cost more and be the right thing to do. Rather, new, more humane, or more respectful interventions have been consistently tied to cost savings.

In the 1950s life at the state hospital was surrounded by cost issues, such as savings earned through new equipment (

275,

276) or whether to have a state hospital farm (

277,

278,

279). In an era when the average state hospital was operating at a cost of $2.70 per capita per day (

280), the introduction of chlorpromazine proved to be a budget buster—pharmacy costs increased 20-fold (

281). That community treatment could be less costly than hospital treatment was recognized in the 1950s (

282).

Mental health care in the 1960s benefited from several policy changes at the federal level. Buildings were in use that had been built with expanded Hill-Burton funds under the Hospital Survey and Construction Act (P.L. 79-725) (

283,

284). Federal welfare payments were extended to conditionally discharged psychiatric patients (

285), and Congress passed the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act of 1963 (P.L. 88-164) (

286). Professionals began to push for better health insurance, including coverage for partial hospitalization (

287). The argument for insured partial hospital treatment was further pursued in the 1970s (

288).

By 1970 it was clear that the absence of federal money for staffing community mental health centers (CMHCs) meant that 60 of those planned would not open or would provide "weak and ineffective programs" (

289). It was also clear that for acute illnesses, short-term hospitalization—two to four days—and immediate return to the community "will not only be expected, but also required" (

290). Further, articles with early data were indicating that individuals who had chronic mental disorders could be cared for less expensively in the community than in the hospital (

291,

292,

293,

294).

By the early 1970s it was starkly apparent that a national plan was needed to simultaneously address financing, comprehensive coverage, and the restructuring of the delivery system. This realization led to the Health Security Program, promoted by the Committee for National Health Insurance (

290,

295,

296). President Nixon also submitted a bill for national health insurance (

297). President Carter, in 1977, indicated that national health insurance was high on his agenda (

298).

A class-action suit that profoundly affected the future of the state hospitals was aimed at requiring the Labor Department to enforce at state hospitals the minimum wage and overtime provisions of the 1966 amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act (

299). The decision in

Souder v. Brennan put a stop to most work done by hospitalized patients (

300), ending both patient exploitation and useful work by inpatients.

The 1980s saw considerable legislative activity that could affect mental health care and treatment. On the federal level it included equal coverage for mental illness in federal employees' insurance (

301), Social Security Disability Insurance (

302,

303,

304), and prospective payment (

305,

306). On the state level there was a focus on minimum inpatient and outpatient benefits (

307). Other economic issues active in the 1980s were the risks of the bottom line overriding patient care needs in for-profit hospitals (

308), the relationship of payment method and hospital use (

206,

309,

310,

311,

312,

313), and the relationship between patient characteristics and the cost of inpatient treatment (

314).

In the 1990s much attention was paid to federal programs or lack of them, including Medicaid (

315,

316), Social Security Disability Insurance (

317,

318), equitable mental health coverage (

319,

320,

321), cost shifting (

322), and national health insurance (

323). However, the major economic focus of the 1990s was managed care, private and public.

Before 1990 most of the focus on managed care had been on health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (

324,

325,

326,

327,

328,

329,

330,

331). In 1990 Dorwart (

332) discussed myths about managed mental health care, including that managed care caused, and that managed care would cure, the current problems of mental health care. Throughout the 1990s managed mental health care rolled itself out, first on the private side and then on the public (

333,

334,

335,

336,

337,

338,

339,

340,

341,

342,

343,

344,

345,

346,

347,

348,

349,

350).

Although this paper cannot do justice to the phenomenon of, issues with, or strengths and liabilities of managed mental health care, it is worth noting that little in private managed behavioral health care, and even less in public managed behavioral health care, is new. Most inventions, attempts at cost savings, and use of alternatives to inpatient care were developed in the public sector long before managed care (

351,

352). People in states that implemented public-sector managed care and the development of community services simultaneously see them as causally linked; those in states that implemented these two service delivery changes consecutively know otherwise.

Empowerment

Neither empowerment of patients nor empowerment of families is of recent origin. The first issue of the first volume of

Psychiatric Services included an item on a "club" formed by patients, ex-patients, and family members (

353) and one on a relatives' organization known as the Friends of the Mentally Ill (

354). Part of the latter group's mission was to seek legislation for better psychiatric facilities and improved treatment.

In the 1950s consideration was given to increasing patients' freedom in the hospital (

355) and to employing patients in the hospital (

356). The importance of patients' engagement in productive work was discussed above. This movement continued in the 1960s with patients' putting out a newsletter (

357); being prepared for competitive employment (

358,

359); working as therapy aides (

360,

361); and helping as hospital volunteers (

362) or as hospital workers (

363,

364). While the state hospital often needed patients to work due to staff shortages, the work programs were seen as vehicles of empowerment and skills training that would better equip patients for life after hospital discharge.

The 1970s continued the efforts seen in the two preceding decades. Patients were helped to obtain jobs (

365), including performing staff members' functions (

366,

367). Emphasis was placed on "normal work environments" (

368). However, a damper was put on most hospital-based work programs with the ruling in

Souder v. Brennan that patients must be paid the minimum wage (

300). An addition to patient empowerment in the 1970s was the introduction of the patient advocate (

22,

369,

370). The advocate's role was not without considerable controversy at the time (

22), and it has remained so.

One term is worth highlighting. Labeling patients or ex-patients "consumers" is not a function of the patient empowerment movements of later years. Rather, the term "consumer" was applied to patients and former patients by psychiatrists of the 1970s (

371).

Two major undertakings of the 1980s were to have profound effects on empowerment for the remainder of the century. The first was the incorporation of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) in 1980 (

372). By the mid-1980s interventions and formal expressions of opinions by NAMI affiliates were affecting mental health policy (

373,

374). The second was the use of self-help groups by those with serious mental illness (

375,

376,

377,

378). As expressed by Estroff (

375) early in the decade, self-help groups were to be "a genuine, not an artificial, partnership in order to solve complex and painful problems." Estroff made a prescient observation—namely, that self-help groups would be more of a challenge for staff than for patients. As for terminology, in another commentary, for the first time an author identified herself in the journal as a "former psychiatric inmate" (

377).

The 1990s were highlighted by persons with mental illness promulgating their own philosophies and definitions of empowerment. Fisher (

379) indicated that the major actions needed to facilitate recovery from disabilities were a change in "the attitudinal and physical environment rather than within the individual, an emphasis on choice in and control of services by the people who are receiving them, and an assertion that it is possible to be a whole, self-determining person and still have a disability." Rogers and others (

19) developed a scale to measure the construct of empowerment, consisting of the three dimensions of self-esteem-self-efficacy, actual power, and righteous anger and community activism.

Further advances were made in areas of empowerment that began in earlier decades, including the employment of persons with serious mental illness as peer interviewers (

380), peer counselors (

381), and case managers (

382,

383,

384). The self-help movement broadened (

379,

385), as did activities for patient advocacy and patients' rights (

386).

Of particular interest is the question of how states' endorsement of patient empowerment translated into actual practice. Geller and associates (

20) found that states' employment of persons with serious mental illness and their family members in state and county offices was inconsistent across the states, and considerably less than it might be. Noble (

387) determined that only 16 state mental health agencies required the inclusion of a vocational rehabilitation component in an individual's treatment or service plan. It would appear that the states' endorsing the empowerment ideology has been much easier than putting anything substantial into practice.

Two related concepts that came into their own in the 1990s were "consumer satisfaction" and quality of life. Although consumer satisfaction was intermittently considered before the 1990s (

388), it had become a focal point, and often a quality indicator, by the century's end (

389,

390). Satisfaction was examined in relation to case management services (

391,

392) and residential options (

393,

394). Studies of satisfaction began to delineate clear distinctions between patients', families', and providers' perceptions of maximal outcomes (

394).

In the 1990s researchers attempted to determine what factors might affect patients' perceptions of their quality of life. One study found that quality of life could be improved by such clinical interventions as family psychoeducation; improved detection, evaluation, and treatment of depression; and more attention to side effects (

395). The effects on quality of life of clubhouses (

396) and of case management (

397) were studied.

And finally, the perception of quality of life by a cohort of 30 patients living in community settings was examined in relation to their perception of quality of life in the state hospital they had been discharged from 11 years earlier (

398). The findings indicated that individuals with chronic, serious mental illnesses, even those with multiple hospitalizations, preferred life in well-staffed community programs to life in the hospital, but that their self-esteem and overall positive feelings had not improved with the transfer to community living.

Many outcomes in this area of research were not necessarily what would have been expected. For example, satisfaction did not improve with decreasing symptoms (

393), alcohol abuse had no independent association with quality of life (

395), and intensive case management did not improve patients' perception of quality of life when compared with standard aftercare services (

397). In order to determine how to improve quality of life, considerably more research is needed to ascertain what professionals contribute to the lives of those with chronic, serious mental illness, beyond providing adequate shelter and meals; what persons with chronic, serious mental illness contribute to their own well-being; and how each group does what it does, separately and together.