Consumers, purchasers, and providers of publicly funded mental health care are interested in using data on patient outcomes to evaluate the performance of treatment organizations and to improve the quality of care (

1,

2,

3). Although outcome assessment methods are often developed for research purposes (

4), it is increasingly common for outcomes to be routinely measured for all patients and for these data to be incorporated into the databases of management information systems.

Although traditional administrative databases often contain information on each patient's demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and treatment utilization, some newer databases have added variables in outcome domains, such as satisfaction, functioning, and quality of life. These new data elements promise to make it easier to study the efficiency and effectiveness of existing programs through analysis of variation in treatment exposure and outcomes (

5,

6). They also provide an infrastructure for evaluating new clinical interventions.

However, there are important challenges to the accurate use of routinely collected outcome data. These challenges are commonly acknowledged to include the need to develop inexpensive, useful, and reliable outcome measures and the need for methods that control for severity of illness (

7). The change over time in the average outcome of a population can be strongly affected by illness severity, because more severely ill patients may improve less than moderately ill patients. However, much less attention has been paid to another major methodological question: what bias is introduced by not having information on patients who become lost to follow-up? Routinely collected outcome data may be entirely unavailable for patients with certain outcomes, potentially biasing evaluations of organizational performance.

Few studies have been done of the direction or magnitude of this bias for patients with severe mental illness or of potential mechanisms for dealing with this problem. Bias due to attrition may be especially problematic in public mental health systems because patients in these systems often have illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder that can cause them to drop out of treatment as their clinical condition worsens (

8,

9).

Studies of mental health treatment have reported that between 20 and 75 percent of patients leave care (

10,

11,

12) and significant variation exists in the outcomes of patients after they leave (

8,

13,

14,

15). Much of this variation in attrition rates and outcomes may be accounted for by differences in the time frames examined and the populations studied. Most studies of attrition have focused on patients who are not severely ill and whose treatment consists primarily of psychotherapy (

16,

17,

18). Surveys of patients with mild or moderate illness have found that reasons for leaving care can be grouped into three categories: no need for services, dislike of services, and environmental constraints (

17).

However, public mental health clinics often focus on treating patients with severe and persistent disorders. In this population, writers have speculated that important reasons for leaving care may include worsening of illness, failing to appreciate the benefits of treatment, being referred to a different program, or being unable to return (

8). For example, people with schizophrenia have a substantially elevated risk of death due to a variety of causes (

19) and are at high risk for incarceration, prolonged hospitalization, and homelessness (

20,

21). Two studies have examined severely ill populations, and both focused on the first five to eight sessions. In these studies, patients who left early in treatment were more severely ill, had less insight into their illness, and apparently failed to engage with the treatment offered (

22,

23).

However, little is known about patients who leave public clinics over longer periods of time or about the degree to which patients who leave actually need further care. Although individuals who are less ill may function without professional mental health care, people with severe illnesses are at high risk for relapse and behavioral problems if, for example, they fail to accept appropriate medication treatment (

24,

25). Furthermore, keeping individuals with severe illness in treatment may require special treatment approaches (

26,

27). Therefore, failing to keep severely ill individuals in treatment may be a sign of poor clinical performance.

The association of patient attrition with particular outcomes may lead to misleading conclusions if we monitor only the outcomes of patients who remain in treatment. For instance, if severely ill patients often leave care and then relapse, their leaving could signal a problem with treatment quality. However, such attrition would result in inflated estimates of treatment success and the outcome status of continuing patients could even appear to improve. Alternatively, if moderately ill patients leave care when they recover, then the clinic may be providing effective care, but these positive effects would not be captured if outcomes were assessed only for continuing patients.

The objectives of this study were to describe patients who left care in one public mental health system, to determine the effect that this attrition had on performance evaluation based on routinely collected outcome data, and to explore whether a follow-up survey of randomly selected patients who had left care could be used to adjust for the effect of attrition. We hypothesized that attrition in public mental health systems is not a random event and that it may often be related to worsening or improvement in patient outcomes. The study used outcome data collected by clinicians using a structured instrument during routine treatment, not as part of a research protocol.

We studied a population of patients in publicly funded treatment in Ventura County, California, between January 1993 and June 1994. Previous analyses used longitudinal data from this population to examine the effect of case management teams on outcomes and costs, and a significant problem was encountered with missing outcome data at follow-up (

28). To describe the population of patients who left care, we selected a random sample of these individuals and interviewed as many as possible about their outcomes and why they had left treatment.

To understand the attrition process, we identified patients who remained in care and patients who left care. Patients who left care (and were still alive) included those who could be interviewed at follow-up and those who could not be interviewed at follow-up. We compared demographic, illness, and outcome variables between these groups at baseline. We also compared changes in outcomes over time between the two groups for which we could obtain follow-up data—that is, patients who remained in care and those who left care but who were subsequently located.

Methods

The study was conducted in Ventura County, California, which is both suburban and rural and has a population of more than 700,000 people. Ventura County Behavioral Health, the county's public behavioral health agency, is the main provider of mental health services to seriously mentally ill adults. At the time of this study, the agency operated one hospital and ten regional community mental health clinics. Clinical case managers routinely collected data on diagnosis, Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (

29) scores, and outcomes of patients treated at community clinics.

Every six months, clinicians were required to record outcome data for each patient in their care using a structured instrument called the Personal Profile. Conformance with this requirement was carefully monitored, and outcome assessment was rarely omitted. The Personal Profile includes information on living situation, income, work activities, physical health status and treatment, drug and alcohol use, social network, educational activities, and legal problems (

28). It consists of a variety of highly structured questions. For example, one question documents the number of paid hours of work during the past week. Another rates the patient's satisfaction with family members on a 5-point scale, from dissatisfied to satisfied.

Patients were included in the study if they had had at least one Personal Profile completed during the one-year period between January and December 1993. This inclusion criterion resulted in a total of 1,769 patients, of which 554 (31 percent) had no follow-up profile during the subsequent six months. From these 565 individuals with missing Personal Profile data, a random sample of 113 was drawn to locate, contact, and interview. Between January and June of 1996, an intensive effort was made to locate these individuals using information from clinicians at the mental health clinic and, when necessary, patients' families, friends, and neighbors.

Sixty individuals were located; two were deceased, and 58 (51 percent) were interviewed by phone. All respondents answered two open-ended questions about why they left the program and what they were currently doing. Responses were independently classified by two raters into categories. Discrepant ratings were discussed, and complete agreement was reached. Fifty-four respondents also agreed to answer questions from the Personal Profile, which was administered by phone by one trained interviewer.

Outcome variables used in these analyses were based on responses to questions in the Personal Profile. A drug or alcohol problem was scored as present if the respondent reported that drugs or alcohol had adversely affected one or more of seven specific functional domains during the past six months. Other outcome domains consisted of responses to one question from the Personal Profile.

Two-tailed tests of statistical significance were used. Statistics were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Therefore, differences with p values of less than .05 should be regarded as tentative and are presented as trends, while values of less than .001 are presented as significant differences. Tests of between-group comparisons were performed using t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables. Tests of change from baseline to follow-up were performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables and McNemar's test for categorical variables.

Results

At baseline, of the 1,769 patients in treatment, 51 percent were female. Sixty-seven percent were white, 23 percent were Hispanic, and 5 percent were black. The mean±SD age was 40±12 years, and the mean±SD GAF score was 46±12. The most common primary diagnoses among the 1,769 patients were schizophrenia (50 percent), major depression (15 percent), bipolar disorder (11 percent), anxiety disorder (5 percent), adjustment disorder (4 percent), and dysthymia (4 percent).

Of the 113 missing patients randomly selected for follow-up, 11 (10 percent) said that they had not, in fact, left the treatment program and were therefore excluded from further data analyses. It is likely that they had temporarily left treatment during the period when their Personal Profile was required.

We learned that two patients were deceased. The 47 respondents gave a total of 73 reasons why they left treatment; some gave more than one reason. The most frequent reasons were that they had improved (15 patients, or 32 percent of respondents), were having problems with the clinician (14 patients, or 30 percent), were having problems with the treatment (11 patients, or 23 percent), or had left the area (12 patients, or 26 percent). Barriers to treatment were cited less often, by only ten patients (21 percent), and included cost, transportation problems, comorbid disorders, and bureaucratic issues. Other reasons included being referred by clinic staff to another program (six patients, or 13 percent), family problems with the clinician (four patients, or 9 percent), and being hospitalized (one patient, or 2 percent).

When asked about their current activities, many of the 49 respondents who left public treatment appeared to be functioning relatively well. Fourteen (29 percent) stated that they were currently working, only two (4 percent) reported living in an institution or residential program, and 19 (39 percent) said they were receiving mental health services elsewhere.

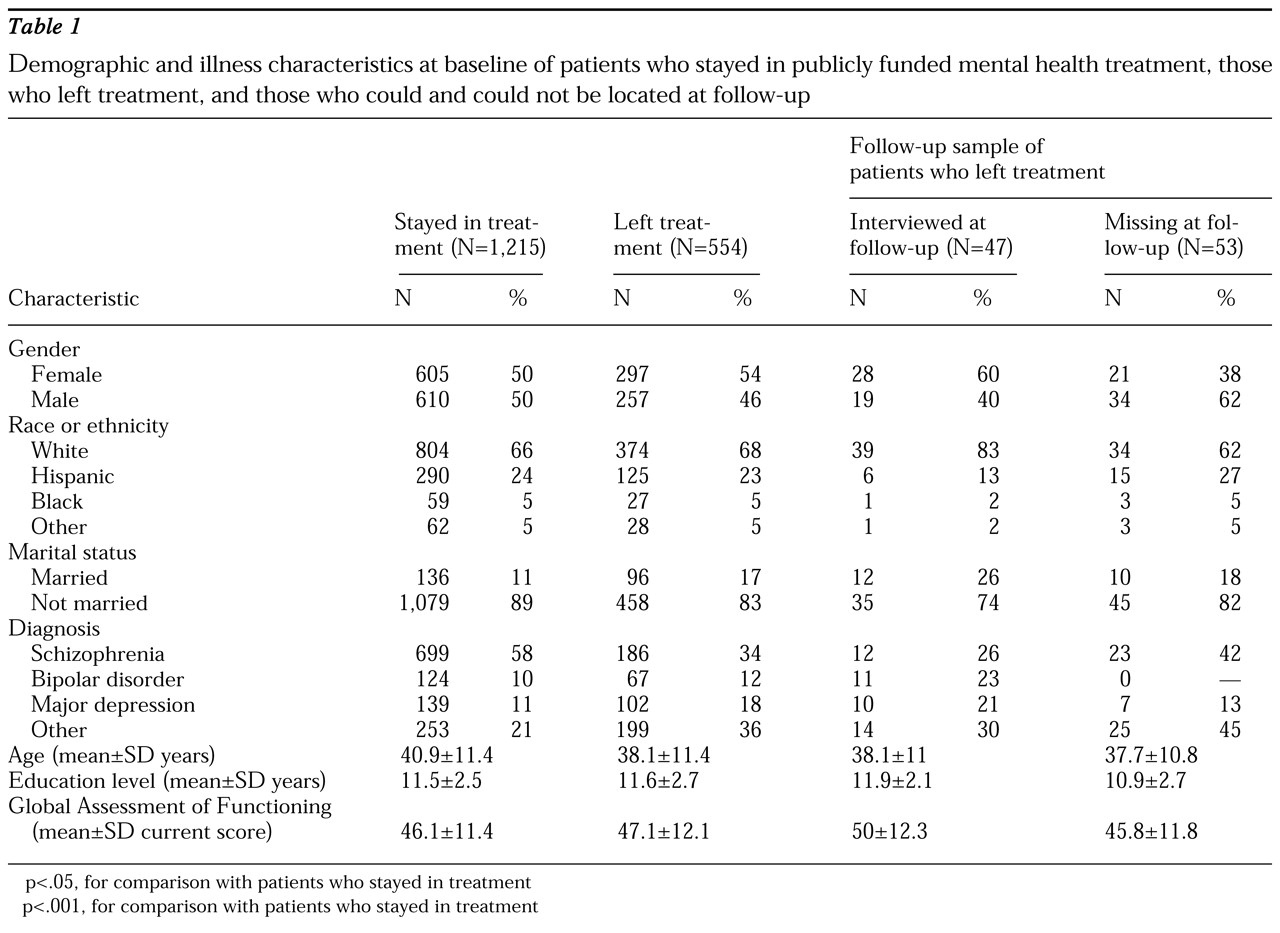

Table 1 presents baseline demographic and illness characteristics for patients who stayed in care, patients who left care, and patients who left care and were randomly selected for follow-up. Significant baseline demographic and clinical differences were found between patients who stayed in treatment and patients who left treatment. Compared with patients who stayed, patients who left were significantly younger (t=4.9, df=1,767, p<.001), more likely to be married (χ

2=12.6, df=1, p<.001), and more likely to have a diagnosis other than schizophrenia (χc

2=18.9, df=1, p<.001). No significant differences between groups were found by gender, race, or educational level.

Patients randomly chosen for follow-up assessment were representative of the overall population of patients who left. However, within the follow-up sample, the group that we could not locate may have been more severely ill. Compared with the group we located, the group that was not located showed a tendency toward being more likely to have schizophrenia and to have a lower mean GAF score. However, the two groups were relatively small, and the comparisons did not have significance levels of .05 (p=.08 for both comparisons).

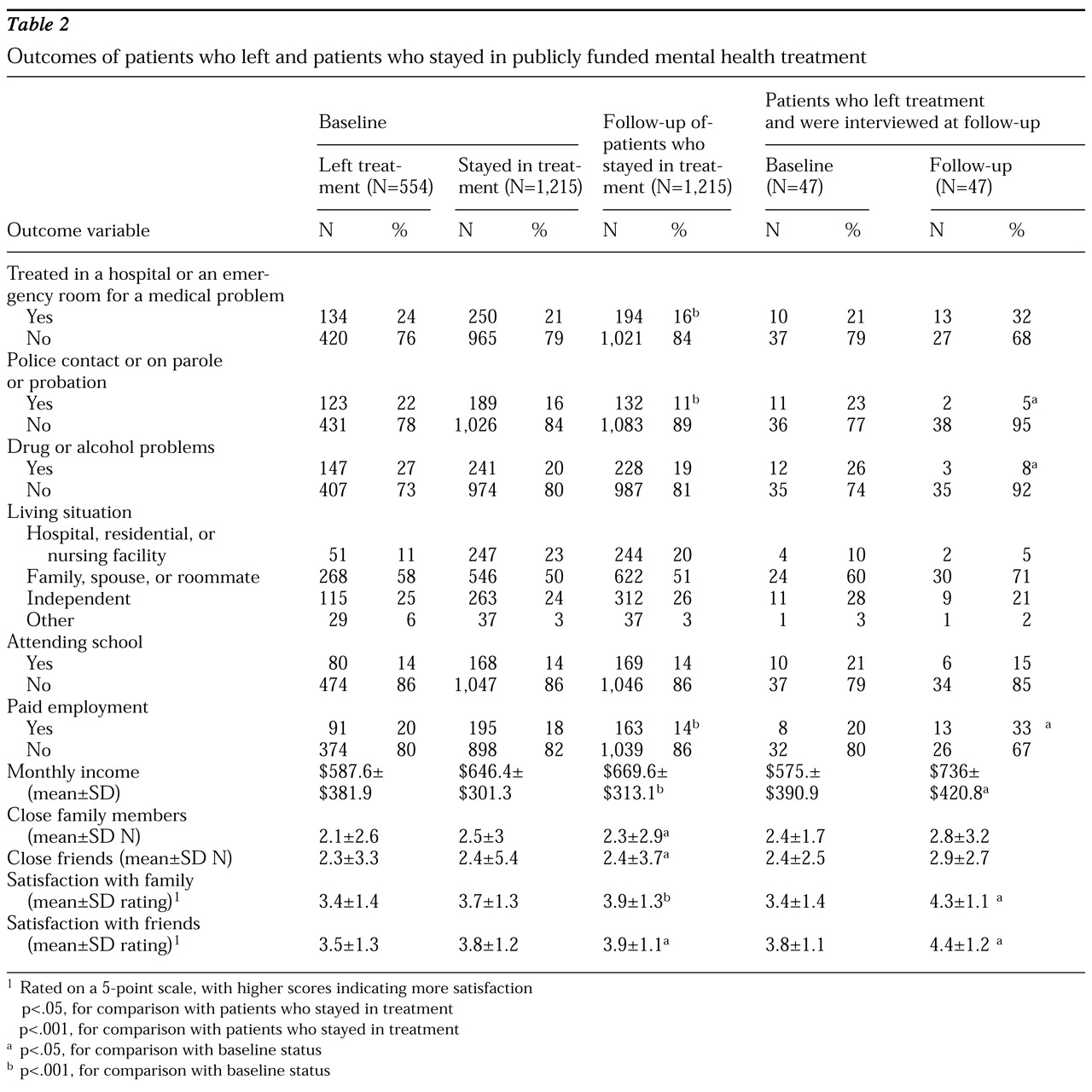

Table 2 presents outcome variables at baseline and follow-up for patients who stayed in care and patients who left care. Significant differences in baseline values of the variables used as outcomes were found between patients who left care and those who remained in care. At baseline, patients who subsequently left treatment were significantly more likely to have legal problems (χ

2=11.6, df=1, p<.001), to be living outside a mental health facility (χc

2= 28.2, df=1, p<.001), and to have lower satisfaction with family and friends (t=4.6, df=1,767, p<001). Trends were also found for patients who left treatment to have more problems with drugs or alcohol at baseline (χc

2=10, df=1, p<05), lower incomes (t=3.5, df=1,753, p<05), and fewer close family members (t=2.8, df=1,765, p<05).

Data from the follow-up interviews were used to compare improvements in outcome over time between the patients who stayed in treatment and those who left treatment and could be located for follow-up. As shown in

Table 2, patients who stayed and patients who left both showed improvements in several outcome domains from baseline to follow-up. However, differences were found between these groups in the magnitude of improvement and the outcome domains in which they improved. Only the group that stayed in treatment saw a significant decrease in acute care for medical problems (χ

2=11, df=1, p<.001) and a significant decrease in paid employment (t=2.8, df=1,202, p<.001). For the group that left care, a trend was noted toward a greater likelihood to be engaged in paid employment (t=3, df=34, p<.05). Among patients who left, a trend was also found toward fewer problems with drugs and alcohol (χ

2=4.5, df=1, p< .05), whereas no significant change was noted in this area among those who stayed.

Both groups improved in several other outcome domains, and the magnitude of improvement appeared to be greater in the group that left care. For instance, both groups experienced decreases in legal problems, improved satisfaction with friends, and greater incomes. However, these changes were noted at only a trend level (p<.05) in the group that left care but were significant (p<.001) in the group that stayed. Both groups had significantly improved satisfaction with their families (for the group that stayed, t=4.4, df=1,214, p<.001; for the group that left, t=3.5, df=39, p<.001).

Discussion

Many publicly funded mental health systems are either planning to monitor patient outcomes or have already begun doing so. For instance, the state of California recently mandated that county mental health authorities collect outcome data on their patients. Although policy makers often acknowledge the need for improved methods and instruments for measuring outcomes, little attention has been given to the extent to which patient sampling can bias evaluations based on routine outcome monitoring. Not uncommonly, relatively few resources are dedicated to outcome assessment, which raises concerns that attrition may not be adequately considered and that most data may be collected from a highly biased, easy-to-reach sample of patients.

This study examined one public mental health system and found that the individuals who left care appeared quite different from those who remained. Nearly a third of patients left care during a one-year period. We were able to locate and interview about half of a random sample drawn from this population. Although a few of the patients who were interviewed had done poorly, most did remarkably well and actually had better outcomes than the group that remained in treatment. Presumably, many of these individuals had recovered from an acute problem and did not need further treatment.

Mental health organizations may attempt to control for patient attrition in analyses of outcome data by randomly sampling a group of patients for intensive follow-up. This approach generally assumes that individuals who are located are representative of the overall population that left care. In this study, one might infer from this approach that evaluation based on routinely collected data underestimated the extent to which outcomes improved, although this bias varied substantially between outcome domains. However, the patients whom we could not locate at follow-up may have been more severely ill at baseline and could have done quite poorly. Also, some mental health clinics may have done a better job than others keeping severely ill patients in care. Although treatment retention would be a sign of better performance, in this population it could easily result in the appearance of worse outcomes at follow-up.

Research projects have successfully evaluated treatment effectiveness by measuring changes in outcomes across defined samples of patients over time (

30,

31,

32). These projects can expend substantial effort following up subjects who leave care and collecting more detailed information about severity of illness than is obtained during routine care. Also, these projects often have focused on patient populations that are quite different from those in public clinics. Patients treated in public mental health settings are frequently poor, have severe mental illness, and are at increased risk for having crises that can suddenly change their clinical and social situations. Housing situations can be tenuous, and patients frequently move to different addresses or locales. Incarceration and institutionalization are common, and rates of death substantially higher than in the general population.

Because treatment programs may be able to affect rates of homelessness, incarceration, and death, these outcomes should be measured as part of any outcome management system. However, in practice it can be difficult to track patients who leave care for these reasons. Our tracking efforts left nearly half of patients unaccounted for. This failure to locate patients is especially remarkable given the fact that Ventura County Behavioral Health provided the vast majority of all public mental health care in the county and much of the area was suburban or rural in character. It may be even more difficult to track missing patients in urban areas with highly mobile populations and fragmented mental health delivery systems.

A limitation of this study is that we did not have a large enough sample to use baseline indicators of illness severity to adjust comparisons between patients who stayed and patients who left. However, it is not clear that accurate information on illness severity is routinely available in public treatment settings such as this one, and case-mix adjustments have often not been very successful when used for psychiatric disorders (

33). Also, there is no way of knowing whether the status of patients who could not be located had improved or worsened, and thus it is unclear whether baseline illness severity can be used to predict outcomes of patients who leave a particular treatment program.

Also, we did not present our findings according to clinical indications for treatment. Although policy makers would presumably be most interested in following up outcomes for patients who continue to need care, this determination can be difficult to make using routinely collected information. Future projects that assertively follow individuals who leave care may wish to include a clinician's assessment of whether the individual has recovered, is being adequately treated elsewhere, or would be expected to benefit from additional care.

It should be noted that the population for this study was drawn from individuals in publicly financed treatment during 1993. Populations in privately financed insurance plans include relatively few individuals with severe mental illness. Thus findings from this study are not necessarily applicable to privately financed care. Also, since 1993 public mental health authorities are increasingly using commercial plans to manage the care they provide. Although our findings might have differed if the care of the population we studied was managed by such a plan, the populations served by such systems are generally similar to those in this study, and little reason exists to believe that attrition has substantially decreased since 1993.

Conclusions

Although outcome data can be used to evaluate quality of care, careful attention must be paid to the sample of patients being assessed. In the public sector, a critical sampling issue is to determine which patients are leaving care, why they are leaving care, and what effect this attrition has on outcomes for a given provider organization. A statistical approach to this problem is based on controlling for the effect of attrition using data collected before patients leave care. However, this approach will not be able to detect whether the causes of attrition differ between provider organizations or whether attrition is associated with improvement or worsening of clinical status. Our findings suggest that outcome monitoring efforts may need to minimize attrition bias by rigorously following a sample of individuals who leave care.

Although we had substantial difficulty locating some of the individuals who left treatment, clinicians can be more successful if they remain in regular contact with patients, work to anticipate and minimize attrition, and quickly seek out patients who become lost to follow-up. Although outcome monitoring has the potential to be a powerful tool for evaluating and improving quality of care in the public sector, threats to the validity of this approach should not be underestimated.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression to Dr. Young; by the UCLA-Rand Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, supported by grant P50-MH-54623 from the National Institute of Mental Health; by grants T32-MH-14583, T32-MH-19127, and R29-MH-57082 from the National Institute of Mental Health; and by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Integrated Service Network 22. The authors are grateful to Ming-yi Hu, Ph.D., and Diana Liao, M.P.H., for assistance with data analysis.