As we have previously reported in this column, the University of Miami Behavioral Health (UMBH), a nonprofit academic managed behavioral health care organization, was awarded a full-risk capitation contract in 2000 from AvMed Health Plan, a nonprofit health maintenance organization, which resulted in a fivefold increase in membership and the successful transition of more than 4,000 active enrollees (

1). After this transition, the UMBH found that members with multiple psychiatric admissions accounted for a major portion of the cost of care. This finding is in accord with other studies of behavioral health plans, which have shown that 5 percent of members accounted for 50 percent of the cost of health care and 20 percent accounted for almost 80 percent of the cost (

2).

Because the best predictor of hospitalization is a history of hospitalization (

3), reducing recidivism offers the best opportunity to affect the quality and cost of care. The UMBH identified poor discharge treatment planning, including problems in scheduling follow-up appointments, and poor adherence to treatment after discharge as major contributors to recidivism. Case management is generally considered to be an effective strategy for reducing such problems and, thus, recidivism (

4). Because case management is time-consuming and expensive in a managed care setting, we reasoned that a telephone-based case management system might be effective for our population. A literature review found no additional research describing ongoing telephonic based initiatives to reduce recidivism in a managed care setting. Our group decided to develop a best practices model that employs telephonic based case management for reducing recidivism.

The care management program

The UMBH was required to improve discharge planning and follow-up so as to achieve best practices. The telephonic targeted care management program developed by the UMBH employed elements from traditional psychiatric case management, disease management, and telehealth care. The major difference from traditional case management programs is that the program employed telephonic interventions without a face-to-face component.

Patients with multiple inpatient admissions in the 12 months before the program was implemented in July 2001 were recruited for the program. Each high-risk patient was telephoned, introduced to the program, and invited to enroll; participation was voluntary. With the member's permission, the program was also explained to identified family members and significant others. Members of the program were flagged in the computer so that their calls could be directed to the program staff. Practitioners and their staff were educated about the program and were told which patients were program members.

A reminder call was made to each program member within 24 hours before each outpatient appointment, and a follow-up call was made to the clinician's office the next day to verify attendance. Attendance and nonattendance were documented, and all occurrences of nonattendance were referred to the care manager. The care manager worked with the nonadherent member, his or her family, and practitioners to assess the situation, conduct a barrier analysis to identify obstacles that contributed to nonadherence, develop alternative strategies, and facilitate early interventions. For members who were readmitted, the care manager worked closely with the acute care team to develop the discharge treatment plan and to schedule follow-up appointments after discharge.

The care manager used various intervention strategies to remove or reduce barriers to follow-up care, such as increasing the frequency of outpatient visits, expanding outpatient treatment to include more intensive programs, requesting consultation between the doctors involved, referring the client to support or self-help groups, and coordinating with health maintenance organizations and primary care physicians.

Our group decided to formally evaluate the effectiveness of the telephonic targeted care management program in July 2002 after the first year of operation. Of the 98 members invited to enroll in the program, 94 agreed to participate (96 percent). Of the 94 members, 60 were eligible for the study on the basis of the following selection criteria: two or more episodes of psychiatric hospitalization during the past 12 months and 24 months of continuous enrollment in the UMBH (12 months before the intervention and 12 months after the intervention).

Our study population had a mean± SD age of 36.7±17.0, ranging from 13 to 79 years. Fifteen members (25 percent) were younger than 18 years, 41 (68 percent) were aged between 18 and 64 years, and four (7 percent) were older than 65 years. Gender was evenly distributed, with 30 males and 30 females. Thirty-nine members (65 percent) had commercial insurance, 13 (22 percent) had Medicare, and eight (13 percent) had Medicaid. Primary diagnoses for the study members were major depression (24 participants, or 40 percent), schizophrenia (14 participants, or 23 percent), bipolar disorder (11 participants, or 18 percent), substance-related disorder (seven participants, or 12 percent), and disorders of childhood or adolescence (four participants, or 7 percent). In the 12 months before the program was implemented, the 60 members who met the criteria accounted for 25 percent of all hospital admissions and 28 percent of bed-days. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Miami.

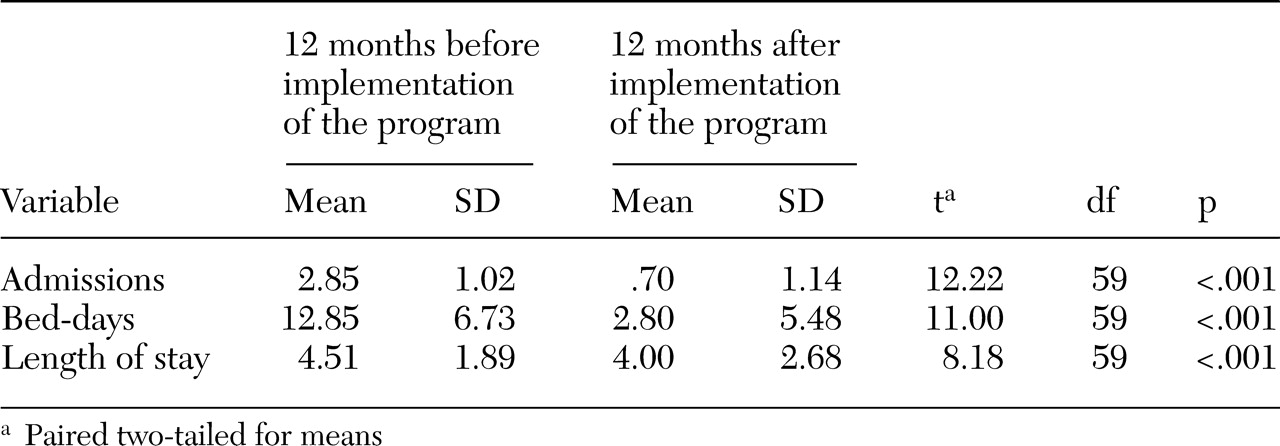

As shown in

Table 1, in the 12 months after the program was implemented, we found statistically significant reductions in admissions, bed-days, and average length of stay (p<.001). Admissions to the psychiatric hospital decreased from a mean of 2.85 per member in the 12 months before the intervention to a mean of .70 per member in the 12 months after the intervention (171 admissions before the implementation compared with 42 after the implementation). Bed-days decreased from 771 before the intervention to 168 after the intervention. The average length of stay for members who were admitted decreased from 4.51 to 4.00 between the two periods. Ninety-three percent of the members (56 of 60 members) had a decrease in total bed-days between the two periods.

In a member-by-member analysis of the 60 participants, four members did not show improvement, three had an increase in the total number of bed-days, and one did not show any change between the two periods. Three of the four members who did not improve had two or more psychiatric diagnoses, and two of the four members had concurrent neurologic conditions.

The impact of the program on cost of care was due mainly to the reduction in bed-days between the two periods and resulted in a cost reduction of $302,706 per year for the 60 members in the program. The expense of employing the two staff members was $104,645 per year, resulting in a net annual savings of $198,061 or a mean of $3,301 per program member.

Discussion

The results suggest that a telephonic targeted care management program can have a positive impact in reducing recidivism in a high-risk population. After accounting for staffing costs, the program reduced acute care expenses by $3,301 per program member. Several critical factors played a role in the success of this program, including the ability to identify, enroll, flag, and monitor high-risk members and to provide ongoing reminder calls and appointment verification. Also crucial was the sensitivity of staff to detect signs and symptoms that would identify members who were at risk of dropping out of treatment. Another critical factor was the ability to direct calls from members to the care manager, who had developed relationships with members and their families, thus optimizing the effectiveness of interventions that were implemented to address the member's nonadherence to treatment. Also important was the knowledge that the medical director and the acute care team could help develop treatment intervention strategies and provide any additional resources. In addition, the case manager was able to coordinate with the behavioral health practitioner to facilitate the integration of care between the behavioral health care practitioner, the primary care physician, and the health maintenance organization.

The study does have limited generalizability because the population served by the program, although severely and persistently mentally ill, was served by a health maintenance organization and, therefore, is not necessarily representative of the population of persons with severe and persistent mental illness in the public sector. The population served by a health maintenance organization is likely to have more economic resources available and may have more social support. The fact that the program was voluntary and some members declined to participate also limits its generalizability. To be effective, the program required phone numbers to be current, and difficulties were encountered in keeping correct phone numbers and addresses for some members. Some barriers, such as the inability to pay copayments and problems with transportation, were identified but could not be resolved by program staff.

Our group established a best practices model, telephonic targeted care management, to reduce recidivism. Although controlled studies will be needed to characterize this model further, we believe that our study sets a benchmark from which to proceed.