National Guard and reserve service members are an integral part of the military and represent up to 50% of the U.S. forces serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Collectively they equal 883,000 members nationwide, and nearly 75% have been mobilized since 2001 (

1). Unique challenges for reserve component members include civilian employment, economic security, health care, and community reintegration. National Guard families are dispersed geographically and do not have the same access to military resources as those living near installations and often feel isolated from the military community. There is limited information pertaining to family members' mental health status along with their usage of services and their perceived barriers to care.

Service members who deploy are at risk of mental health problems, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (

2–

4). Hoge and colleagues (

5) reported that after deployment to Iraq, National Guard (21%) and reserve (21%) troops screened positive for a mental health problem at a higher rate than active-duty (18%) members. Combat deployment for reserve and National Guard members has been associated with the onset of binge drinking and alcohol-related problems (

6). Symptoms of mental disorders place all veterans at additional risk of suicide (

7), up to eight times higher than that of the general population (

8,

9).

Deployment to a combat zone also places stress on troops' families and can affect the mental health of spouses or significant others (

10,

11). Military spouses receiving primary care on military installations showed mental health problems at rates similar to those of their Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)-Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) service member (

10). Among the National Guard and reserve members, 21% expressed concerns about interpersonal conflict on their Post Deployment Health Reassessment (PDHRA), whereas only 4% did so three to six months earlier on the initial postdeployment assessment (PDHA)—a significant difference (

12). Negative interactions within the family system can intensify the development and continuation of PTSD (

13,

14). With 51% of National Guard and reserve members being married (

13), considerations should be made for the mental health problems of the family in addition to that of the service member.

Mental health utilization is associated with a high level of stigma within the military (

4,

15). Studies indicate that although nearly one in five veterans screen positive for some mental health impairment, less than 40% with an identified mental health problem seek treatment. Service members express real and perceived fears that notations about mental health service use in their military records would prevent them from completing missions, redeploying, or receiving an earned promotion (

2,

15,

16).

The purpose of this study was, first, to identify symptoms of mental health problems in a sample of National Guard members and their significant others after service members' return from OEF-OIF deployment and, second, to identify whether mental health services were utilized in the 12 months before the study assessment, the types of mental health services utilized by National Guard members and their significant others, and perceived barriers that would affect the participants' decisions to receive treatment. The guiding research question for the study was, “What are the mental health problems identified in a sample of National Guard service members and their spouses after returning from OEF-OIF, what types of mental health services do they report using, and what barriers do they identify related to mental health service utilization?”

Methods

Participants were recruited from among National Guard members and their spouses or significant others who were participating in one of nine reintegration workshops between October 2007 and August 2008 at conference centers in the Midwest. The reintegration workshop was mandatory for all returning National Guard service members and was optional for all family members. The two-day programs took place approximately 45–90 days after service members' return home from a 12-month deployment. Service members may have had additional time away from family for premobilization training. The sample included members from the following Military Occupational Specialties: infantry, transportation, service personnel, medical, military police, and security force. Attendance at the nine reintegration programs included 826 National Guard members and 588 family members. Workshop participants were told about the study during a general session. Service members and persons in a committed relationship with them (“significant others” used hereafter) were invited to participate. Of the National Guard and family members present during study recruitment, 332 National Guard members (40%) and 212 significant others (36%) volunteered to participate.

The study was conducted with consideration for human subject protection and followed the protocol approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board. Informed consent information was provided to potential participants, who were briefed about their rights as participants and the potential risks associated with participation. Even though data were collected at the site of a military meeting, this meeting was formally adjourned and participants were free to leave the room before data collection. Emphasis was placed on the voluntary nature of the study. All data were collected with no identifying information and with an emphasis on anonymity. Participants deposited their completed surveys into a closed box; however, absolute anonymity could not be assured because study team members were involved in data collection. Participants received a $10 gift card for their voluntary participation.

We assessed psychiatric symptoms in relation to PTSD, depression, suicidal ideation, and hazardous alcohol use. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M) (

17) is a 17-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms. Using the reference point of the previous 30 days, respondents were asked to answer each item in regard to their most distressing military event. A 5-point Likert scale was used, with responses ranging from 1, “not at all,” to 5, “all the time” (

5). The PCL-M can be used as a continuous measure of symptom severity by summing scores across the 17 items. Congruent with similar studies, participants were identified as meeting the criteria for a likely PTSD diagnosis if they had a PCL-M score of 50 or higher (

2,

17). The Cronbach's alpha for this study was .95. The PCL-M correlates strongly with other measures of PTSD, such as the Mississippi Scale, the PK scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2, and the Impact of Events Scale for PTSD (correlations range from r=.77 to r=.93) (

18).

The Stressful Life Event Screener was used to identify and reference traumatic life events of significant others in relation to nonmilitary events. This screening measure was adapted from Goodman and colleagues' Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (

19). Presented with a list of 15 stressful life events, respondents indicated whether they had experienced any of the events, as well as the event that was most distressing. In reference to their most distressing life event, significant others were asked to complete the Short Screening Scale, which assessed for PTSD symptoms (

20). The Short Screening Scale for

DSM-IV PTSD (

20) is a seven-item self-report measure of PTSD symptomatology. In this study the Cronbach's alpha for the scale was .84. Significant others were identified as meeting the criteria for likely PTSD if they had a score of 4 or higher (

20).

The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) (

21) was used to identify depression symptoms. This 21-item self-report inventory is effective in discriminating among individuals with various levels of depression, ranging from minimal to severe. The BDI-II has a high internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of .91. Similar to other studies (

22–

25), in this study a total score of 14 or greater on the BDI-II was the criterion for having depression.

Suicidal risk was assessed with the BDI-II question assessing suicidal thoughts. Individuals were considered to have risk associated with suicidality if their responses endorsed one of the following statements: “I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out,” “I would like to kill myself,” or “I would kill myself if I had the chance.”

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (

26) was used to assess for hazardous drinking. This ten-item self-report measure has been found to provide good discrimination across genders and multiple cultures and socioeconomic groups. The AUDIT showed a high reliability (r=.86) with a sample of nonhazardous drinkers, cocaine abusers, and persons with alcohol dependence (

27); the Cronbach's alpha was .80 for this sample. Total scores of 8 or more indicated hazardous and harmful alcohol use.

An additional dichotomous variable was created to ascertain the presence of one or more identified mental health problems. A positive response was recorded for an identified mental health problem if someone met the study criteria for PTSD, depression, suicidal ideation, or hazardous alcohol use. Health care utilization was assessed by asking participants whether they had received mental health services during the prior 12 months for a problem related to stress, emotional issues, alcohol, or family. Participants indicated a yes or no response to a list of ten military and civilian providers. Questions assessing perceived barriers to seeking mental health services were adapted from a study by Hoge and colleagues (

2) to address not only concerns of the National Guard service member but also to include issues relevant to significant others. Respondents were asked to rate each of the possible concerns that might affect their decision to receive mental health services. Five possible responses ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Agree and strongly agree were considered an indicator of a perceived barrier to care.

Results

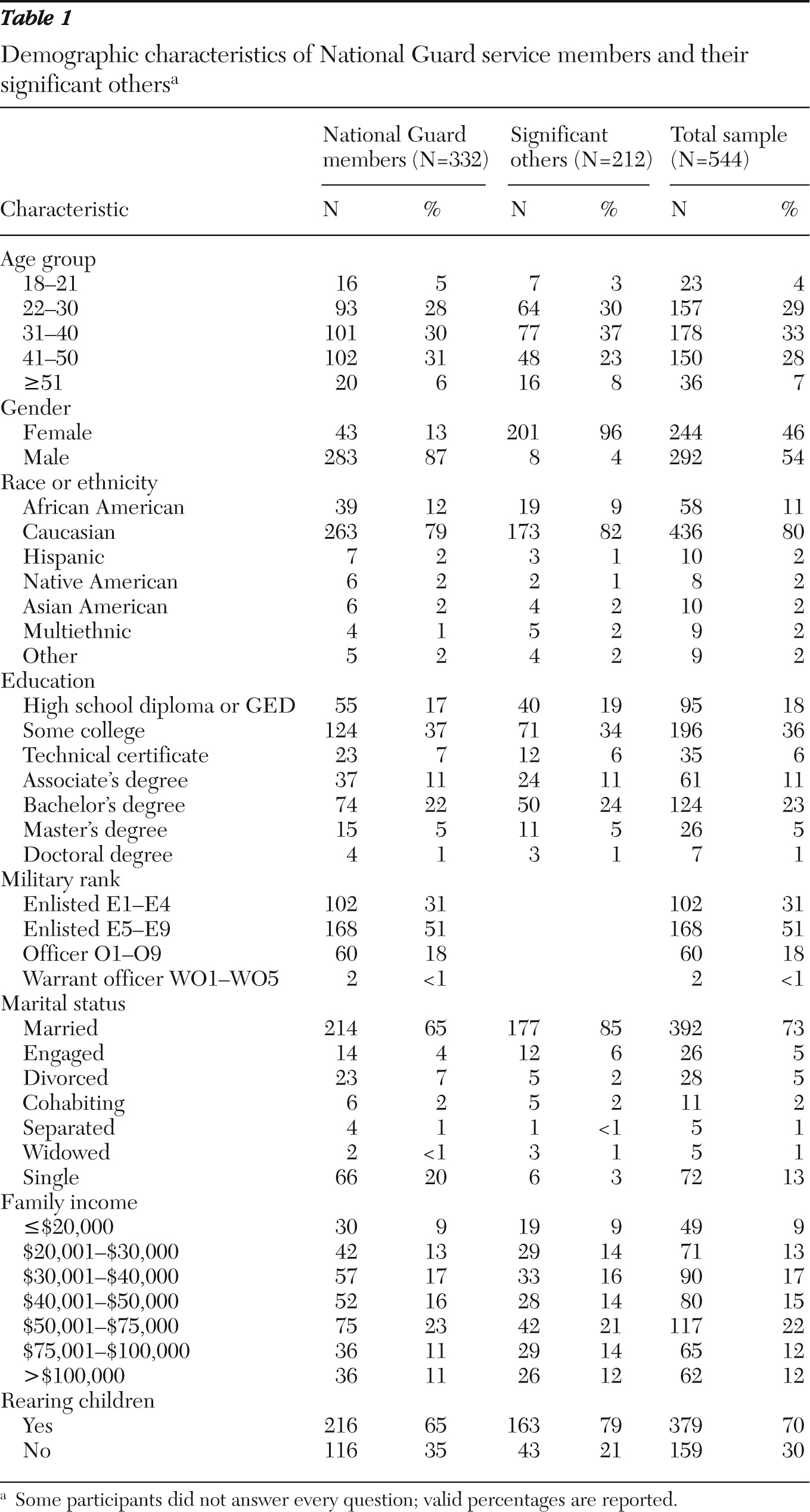

Service members ranged in age from 18 to 60, with 89% of respondents in the 22–50 range (

Table 1). A majority of the service member respondents (87%) were male, Caucasian (79%), and relatively well educated, with 83% having education beyond a high school diploma. Seventy-one percent were either married or in a committed relationship. Demographic characteristics for significant others were similar, with a majority being 22–50 years old, female, and Caucasian. When demographic characteristics of our participants were compared with those of the Army National Guard (

13), some differences were notable, including an underrepresentation of people from racial-ethnic minority groups and young soldiers aged 18–21, as well as more married service members and more participants with children. At the reintegration event, younger soldiers were less interested in completing a survey, whereas soldiers who were married seemed more willing to volunteer. Only 5% of the sample was in the 18–21 age group, although nationally there are reportedly 31% under the age of 25 (

13). Sixty-five percent of the service member participants were married, 65% were parents, and 21% were from minority groups, compared with national figures of 51%, 43%, and 20%, respectively (

13).

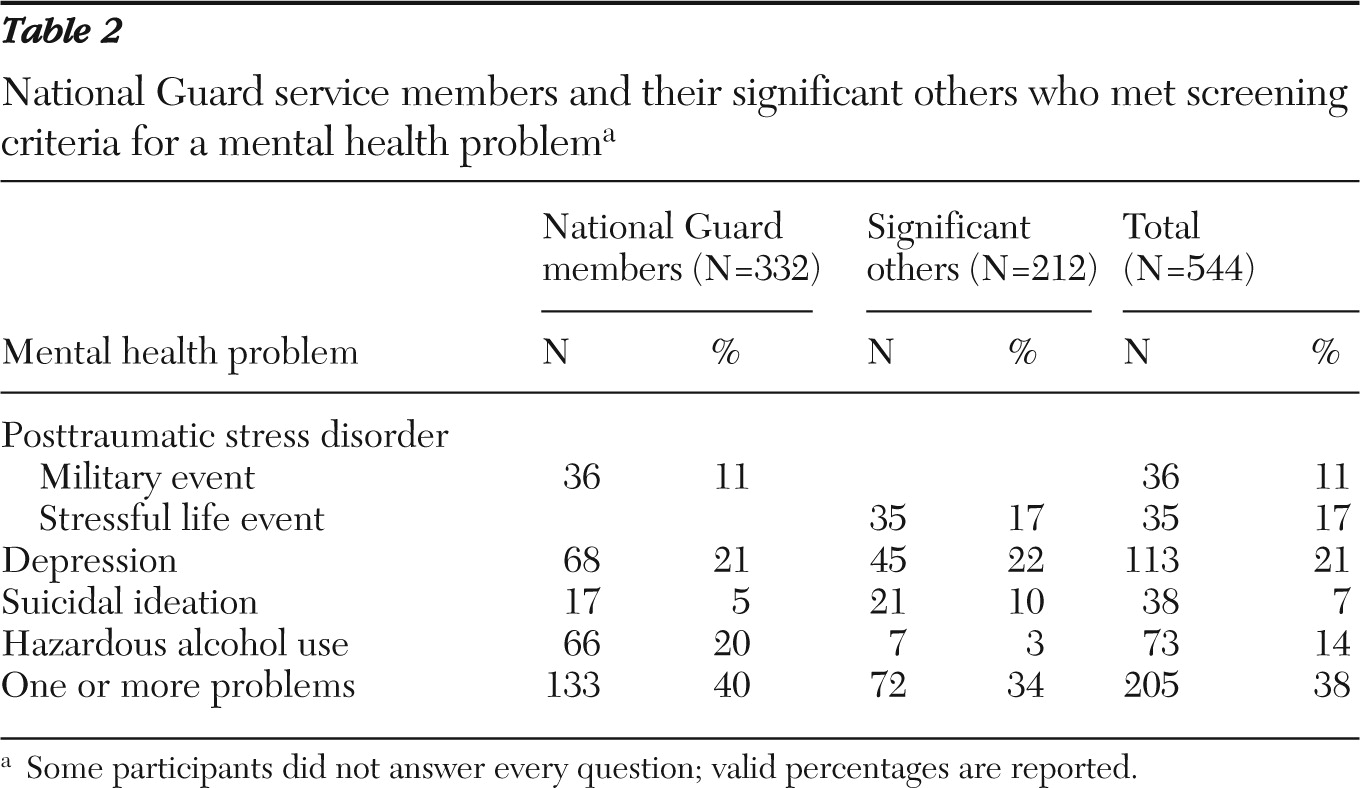

Table 2 presents the incidence of mental health problems in our sample. Forty percent of National Guard members and 34% of their significant others met the screening criteria for at least one mental health problem. Significant others indicated symptoms that met the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis (17%), depression (22%), suicidal ideation (10%), and hazardous alcohol use (3%). National Guard members indicated symptoms that met the criteria for PTSD diagnosis related to a military event (11%), depression (21%), suicidal ideation (5%), and hazardous alcohol use (20%).

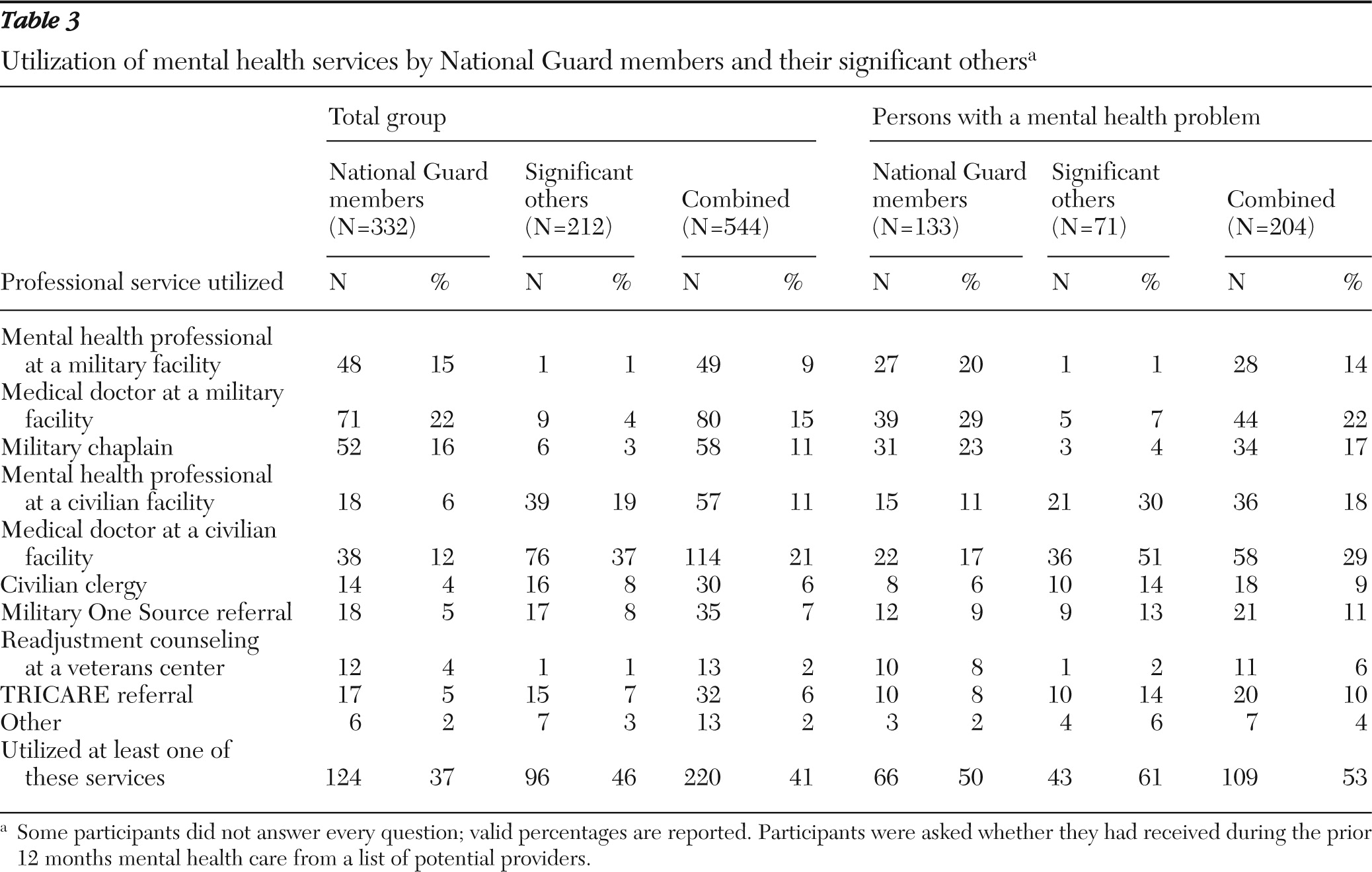

Table 3 summarizes utilization of mental health-related services. Findings indicate that among those meeting the criteria for a mental health problem, 47% reported no utilization of mental health care services in the past year. During the previous 12 months, which included deployment to a combat zone and approximately 45–90 days of reintegration into the family, the four services used most frequently by all National Guard members in the sample were from a medical doctor at a military facility (71 of 330, 22%), a military chaplain (52 of 329, 16%), a mental health professional at a military facility (48 of 329, 15%), and a medical doctor at a civilian facility (38 of 329, 12%). Significant others reported receiving services mostly in the private sector, largely from a medical doctor at a civilian facility (76 of 206, 37%) or a mental health professional at a civilian facility (39 of 207, 19%). Mental health services intended to support families during deployment and reintegration stresses were underutilized by this sample: Military One Source (35 of 533, 7%); TRICARE referral (32 of 532, 6%); and readjustment counseling at a veterans facility (13 of 532, 2%). Of those with at least one mental health problem, only 53% reported talking to someone on the list.

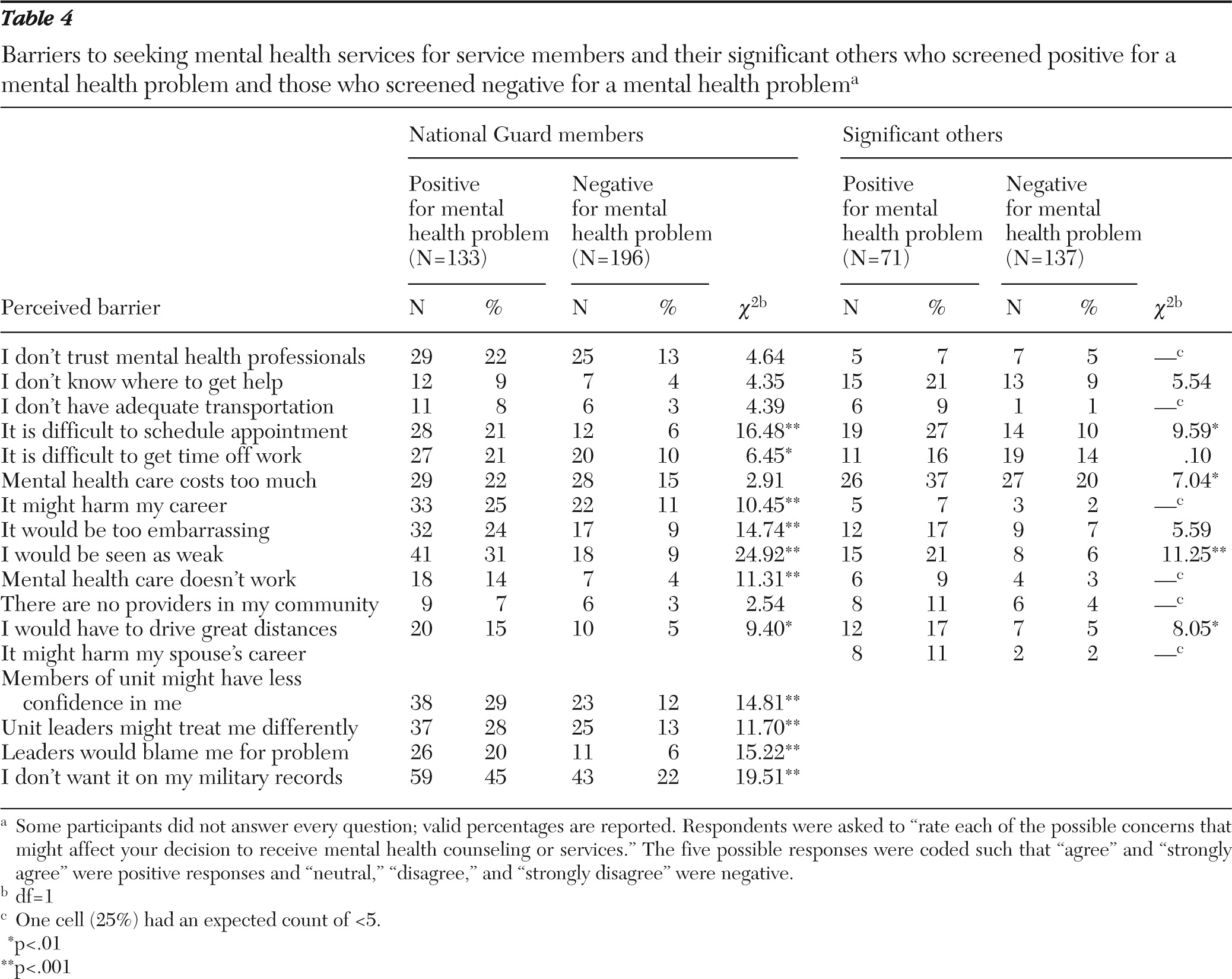

Perceived barriers to mental health care for National Guard members and their significant others are shown in

Table 4. Our data indicate the perceived barriers to receiving mental health care for National Guard soldiers were less than those perceived by active U.S. Army and Marines sampled in 2003 (

2). For example, 28% of National Guard members with identified mental health problems and 13% without identified mental health problems responded that “My unit leadership might treat me differently,” compared with 63% of the earlier sample of soldiers and marines who met screening criteria for mental problems and 33% of those who did not meet the screening criteria for a mental problem (

2). The greatest concern in our sample of National Guard members was having mental health care appear on their military records. This concern was reported by 45% (59 of 132) of soldiers who met the screening criteria for at least one mental health problem and 22% of soldiers who did not. Stigma (43 of 195) continues to be an important factor in the decision to receive mental health care. To test the relationship between having an identified mental health problem and perceived barriers to seeking mental health care, we used a chi square test of independence. Many barriers were significant (p<.001) for soldiers: difficulty scheduling appointment, possibly harming career, too embarrassing, being viewed as weak, mental health care seems ineffective, unit members having less confidence in him or her, leaders might treat soldier differently or blame him or her, and not wanting mental health care to appear on the military record.

Findings for the sample of significant others indicated other concerns (

Table 4). In this group, mental health care cost was most likely to affect their decision to receive mental health counseling. Cost was an issue for 37% (26 of 71) meeting the screening criteria for at least one mental health problem and 20% (27 of 136) not meeting those criteria. Other statistically significant barriers for significant others included difficulty scheduling an appointment, difficulty getting time off work, being viewed as weak, and having to drive great distances to receive high-quality care. Compared with those without mental health concerns, the only barrier that was significant at the p<.001 level for significant others with such concerns was being viewed as weak.

Discussion

The prevalence of mental health problems among returning service members (40%) in our sample is similar to earlier screening results on the PDHA and PDHRA, in which 42% of reserve component soldiers (

12) were identified as needing treatment of some kind. Our study extended earlier findings of an increase in depression diagnoses among Army wives with each 12-month deployment (

11). And like significant others of active-duty members (

10), with National Guard significant others the prevalence of mental health problems was similar to that of service members postdeployment. In this study, nearly one in five significant others reported symptoms of PTSD and depression in a clinical range, and one in ten reported suicidal thoughts. Because there are substantial differences by sex in the prevalence of disorders such as depression and PTSD, interpretation of similarities or differences between National Guard members and significant others in this sample should be done with caution, given that 87% of National Guard members in our sample were male and 96% of significant others were female.

Even though mental health services to help families cope with deployment and reintegration were underutilized as a whole, of those with an identified mental health problem, significant others (61%) were more likely than soldiers (50%) to have talked to someone about their mental health problem in the prior 12 months. National Guard families are far more likely than their active-duty counterparts to receive care from civilian service providers (

10). Because National Guard significant others are most likely to receive help from physicians and mental health professionals at a civilian facility, efforts should be made to raise awareness of military family experiences with these providers.

The reduction of stigma related to utilization of mental health services remains a challenge across the military and civilian communities. Educational and outreach strategies are needed on all system levels to raise awareness and open pathways for early intervention and treatment. Community engagement and awareness of deployment experiences are needed to provide greater accessibility to high-quality services for National Guard families receiving care in the private sector (

28). Furthermore, because significant others of National Guard members are more likely than those of U.S. Army members to perceive cost as a barrier to care (

10), policy should address reimbursement issues for these families, given their limited access to military treatment facilities. Policy should ensure that no veteran or veteran's family member is penalized for psychological injuries sustained as a result of a combat-related deployment. This is especially true for National Guard members, who return to civilian communities and, in most cases, to nonmilitary employment. Furthermore, if a psychiatric diagnosis associated with combat duty has occupational effects, it will further complicate the multiple stressors that these families face (

29).

Methodological limitations of this study include that the sample was limited to National Guard members and significant others living in the Midwest who were attending a reintegration workshop. Attendance at the workshop itself could have affected survey responses. Although the reintegration program was mandatory for service members, some of their significant others were not in attendance because of family or work obligations. Furthermore, we did not have information about the individuals who attended the reintegration event but chose not to participate in the study. Although every effort was made during the study assessment to maintain anonymity, some participants may have been inhibited in their responses if they chose to remain in proximity to their significant others or military colleagues. Finally, the cross-sectional design allowed for only a onetime assessment of these participants shortly after service members returned home.