Inpatient admissions frequently occur in the community management of schizophrenia. The risk of psychiatric hospital admission for schizophrenia exceeds that for bipolar disorder, depression, and other psychiatric disorders (

2). In the United States there are more than 800,000 hospital admissions each year for treatment of schizophrenia at an aggregate cost exceeding $3 billion (

3). The average length of inpatient stays for schizophrenia exceeds that for other major psychiatric disorders (

3).

Several factors appear to influence risk of psychiatric hospital admission among individuals with schizophrenia. Risk tends to increase with antipsychotic medication nonadherence (

4), poor global functioning (

5), and co-occurring substance use disorders (

5). Patients with previous psychiatric hospital admissions (

5,

6) and past suicide attempts (

6) are also at high risk of future hospital admission. In addition, younger adults with schizophrenia are at greater risk than older adults (

6). Consistent differences in rates of hospital admission for schizophrenia patients, however, have not been shown to be related to patient marital status or gender (

7), though men with schizophrenia tend to spend more time in the hospital than women with schizophrenia (

8,

9).

Little is also known about the role of symptom type or severity in predicting inpatient admission. Depressive symptoms, for example, sometimes (

5), but not consistently (

10), have been associated with relapse or hospital admission among individuals with schizophrenia. Methodological limitations have constrained progress in clarifying risk factors for hospital admission among individuals with schizophrenia. Much of the research has involved medical claims that lack diagnostic precision and clinical detail. Other methodological limitations include reliance on cross-sectional rather than on prospective designs (

11,

12), use of diagnostically mixed psychiatric samples (

11), and study of comparatively few individuals (

10).

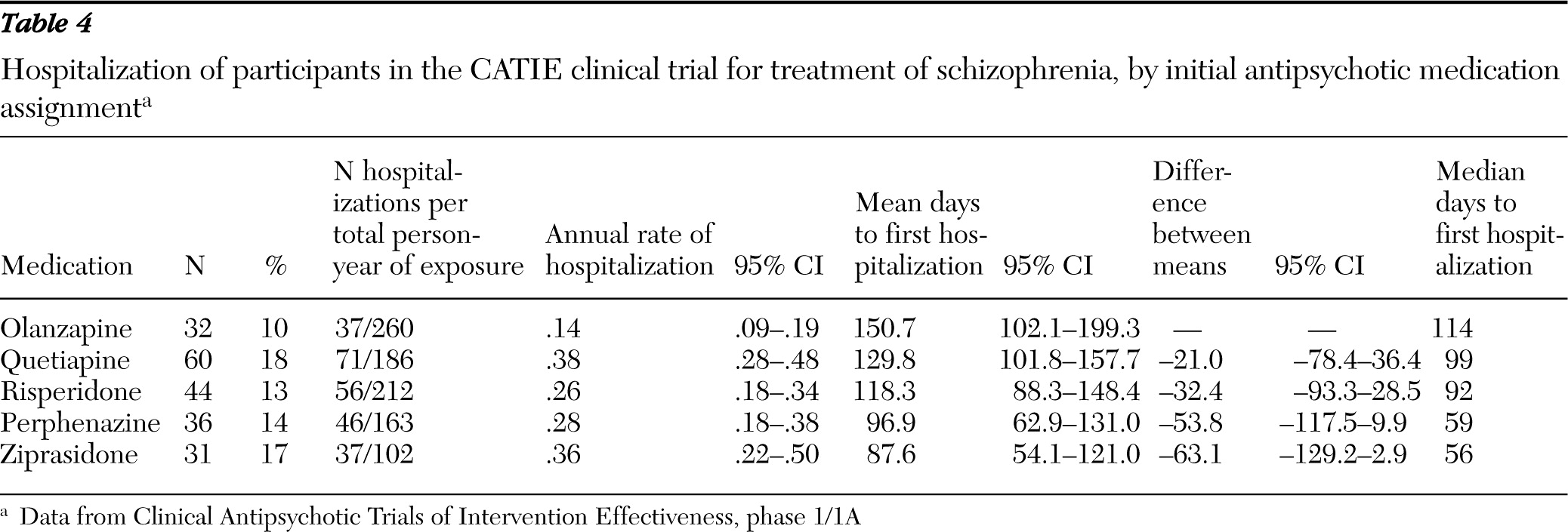

This study examined risk of psychiatric hospitalization among individuals who were enrolled in the first phase of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) clinical trial. The first phase followed a well-characterized cohort of adults with schizophrenia for up to 18 months or until antipsychotic treatment was discontinued for any reason. According to a previous report, the percentage of CATIE participants who were hospitalized during the first phase significantly varied by medication assignment—olanzapine, 11%, risperidone, 15%, perphenazine, 16%, ziprasidone, 18%, and quetiapine, 20% (

13). This report extended this analysis to examine associations of factors related to patients, including sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric symptoms, psychiatric comorbidity, and treatment history, with risk of psychiatric hospital admission.

Methods

Source of data

Data were drawn from phase 1/1A of the NIMH CATIE study, which compared the effectiveness of antipsychotic medications (

13). Adults who were between the ages of 18 and 65 years and who were diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

14) as meeting criteria for schizophrenia were randomly assigned as outpatients to receive olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone under double-blind conditions. Phase 1A included patients with tardive dyskinesia who were otherwise eligible for the study and were randomized to olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone but not to perphenazine. Participants were followed for up to 18 months or until the assigned medication was discontinued. Schizoaffective disorder, mental retardation, or other cognitive disorders, as well as a documented serious adverse reaction or clinical nonresponse to any study medication, were exclusion criteria. Patients in their first episode of schizophrenia, pregnant or breast-feeding women, and patients with serious and unstable medical conditions were also not eligible.

Deidentified data were obtained from the NIMH Limited Access Clinical Trial Data program. This project was determined to be exempt from human subjects review by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board.

Sociodemographic characteristics

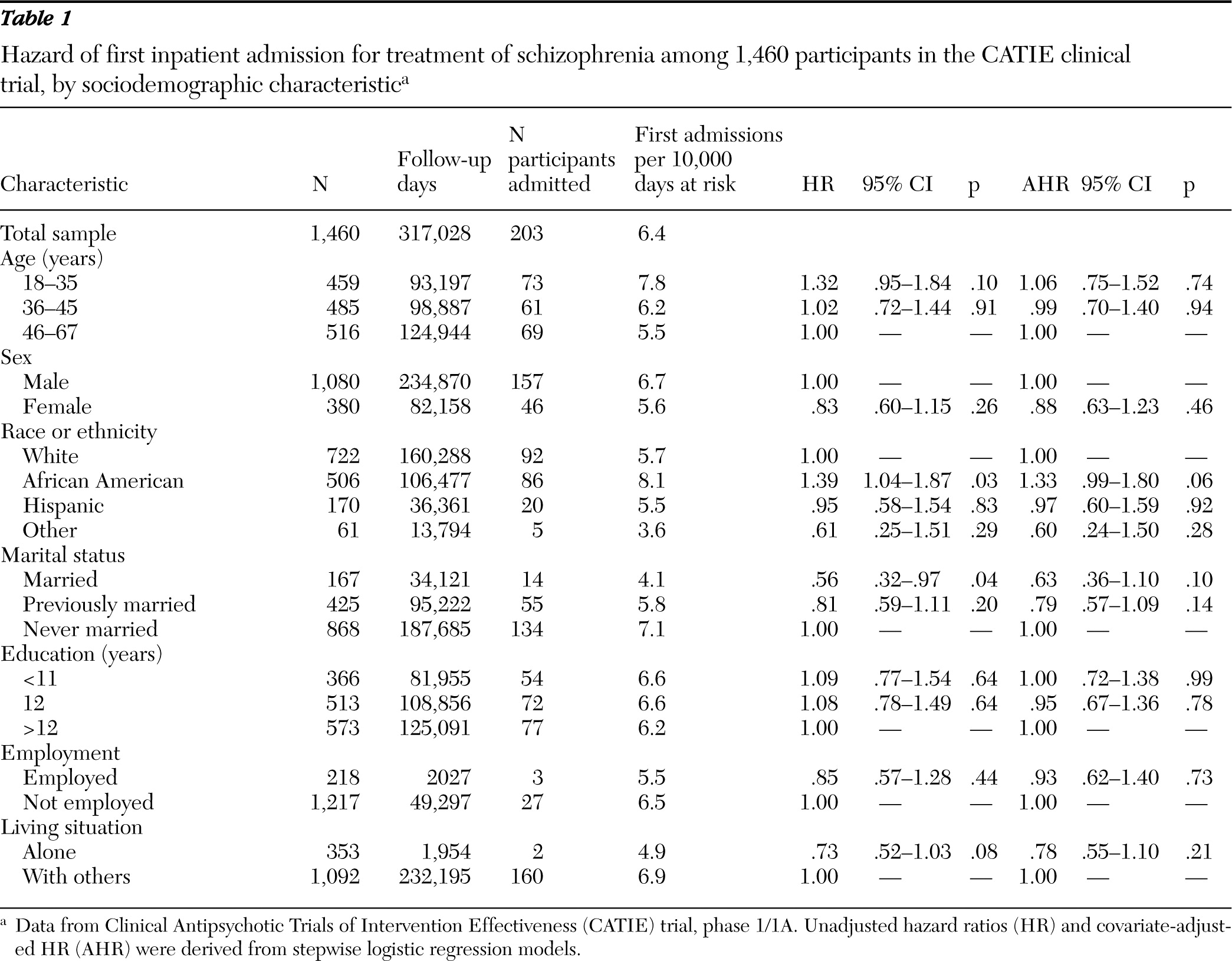

At baseline, a sociodemographic assessment was performed. We classified patients by age in years (18–35, 36–45, and 46–65), sex, race or ethnicity (white, African American, Hispanic, or other), marital status (married, previously married, or never married), highest level of formal education in years (0–11, 12, or >12), current employment status (full- or part-time employment or not employed), and living situation (alone or with others).

Clinical characteristics

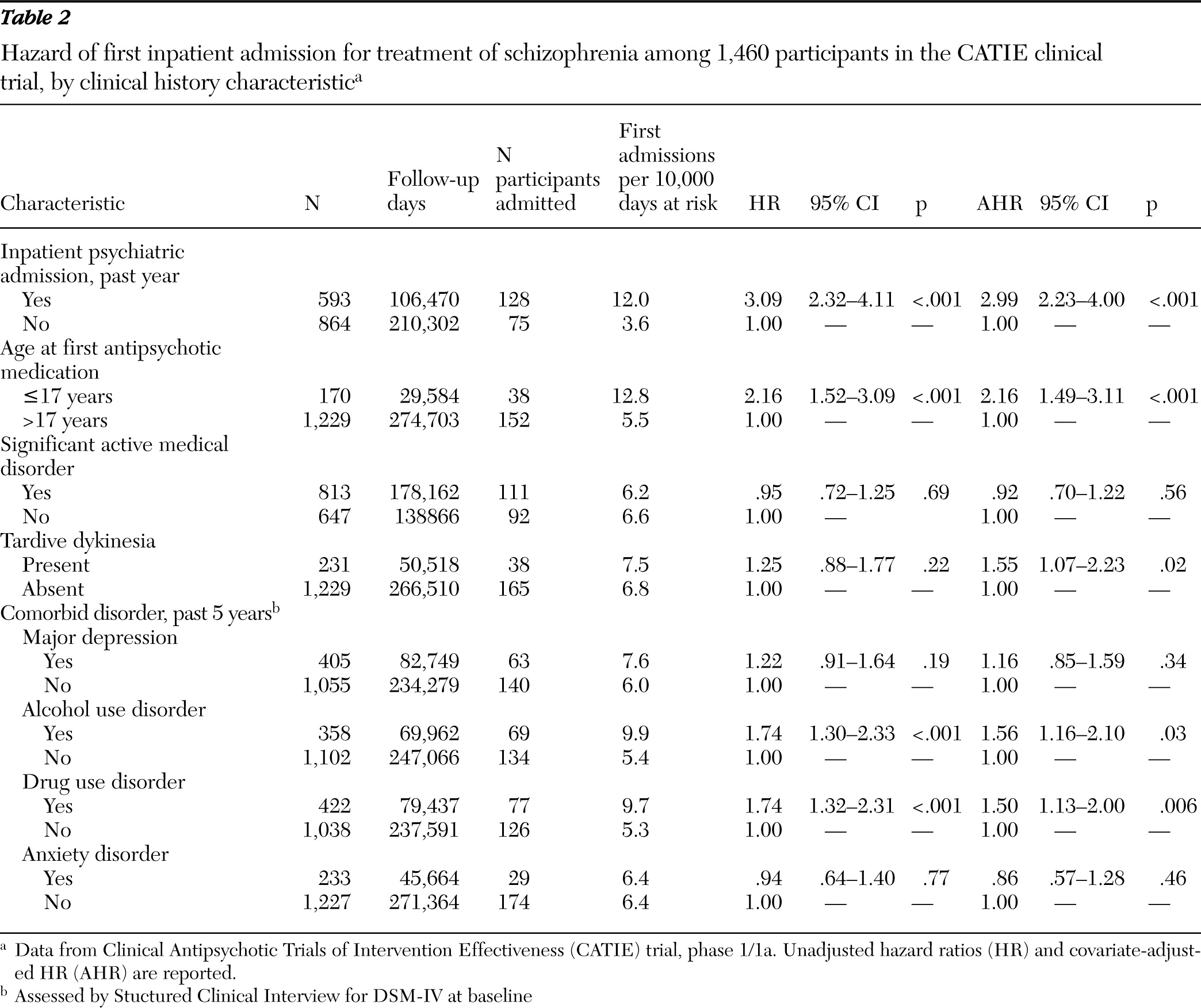

Patients were also characterized at baseline by having experienced one or more episodes of inpatient mental health care in the past year, age of first antipsychotic medication use (≤17 or >17 years), and a self-report measure of lifetime intentional physical injury of others (

15). On the basis of the SCID (

14), patients were assessed for major depressive disorder, alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, and anxiety disorders during the past five years. The Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (

16) at baseline classified patients with respect to probable tardive dyskinesia, defined as a moderate (≥3) rating on at least one AIMS item or a mild (≥2) rating on at least two items (

17).

Symptom measures

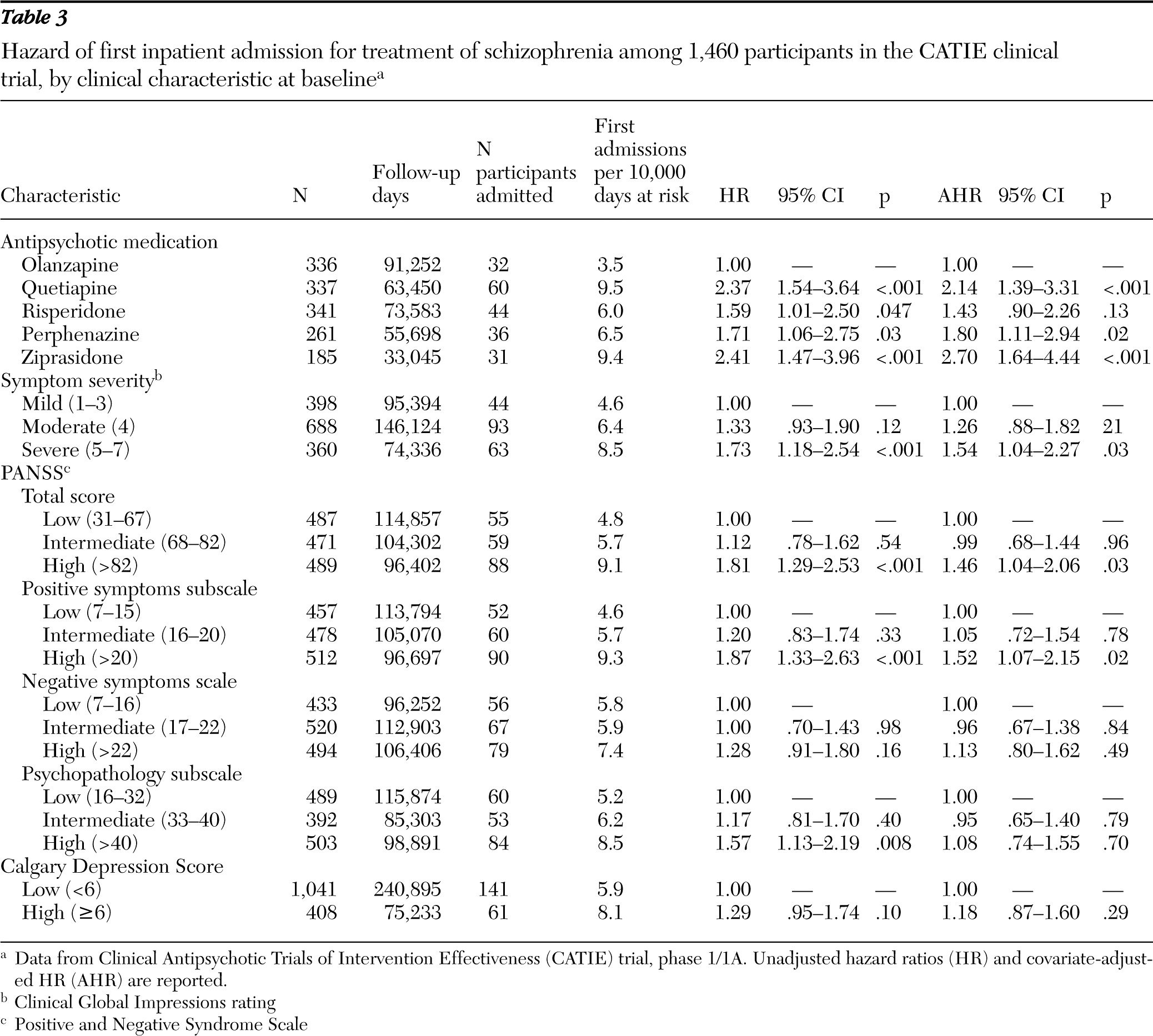

Symptom severity was assessed at baseline with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (

18). Low, intermediate, and high severity tertiles were constructed for the PANSS total scale (30 items) and for the positive symptom (seven items), negative symptom (seven items), and general psychopathology (16 items) subscales. Results for clinician-rated Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale at baseline were coded as mild (ratings of 1–3), moderate (rating of 4), or severe (ratings of 5–7). Baseline ratings for the nine-item Calgary Depression Rating Scale were used to assess severity of depressive symptoms as either low (<6) or high (≥6) (

19).

Antipsychotic medications

According to medication assignment, patients were classified as receiving treatment with olanzapine, perphenazine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone. Ziprasidone was included following its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration during the recruitment period, and patients with current tardive dyskinesia were systematically excluded from assignment to treatment with perphenazine (

13).

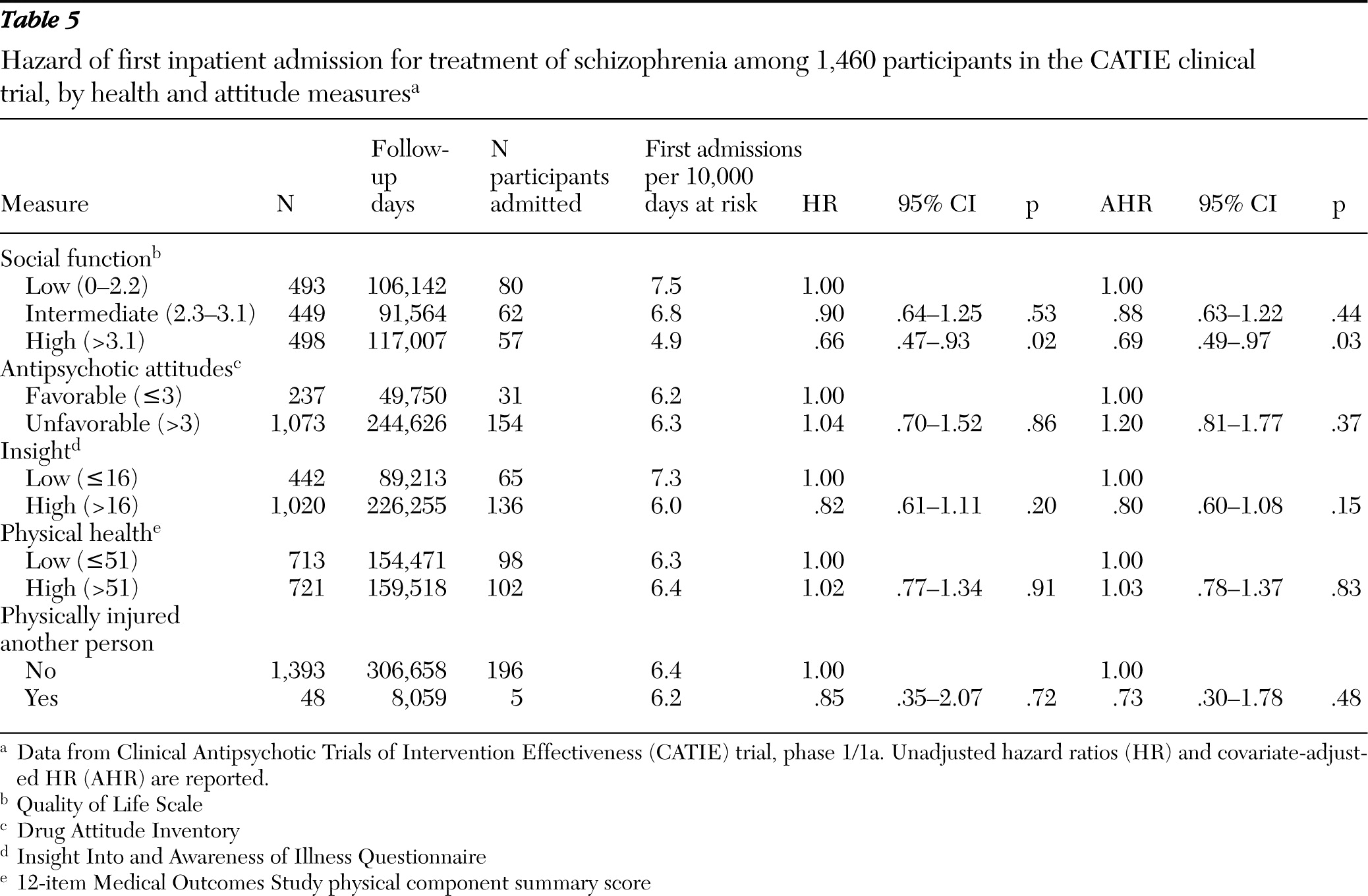

Health and attitude measures

Social functioning was measured at baseline with the 21-item clinician administered Quality of Life Scale (

20). Total scores were classified in low (0–2.2), intermediate (2.3–3.1), and high (>3.1) tertiles. Subjective response and attitude toward antipsychotic medications were assessed with the ten-item Drug Attitude Inventory (

21); scores ≤3 were considered favorable and scores >3, unfavorable. The 11-item Insight Into and Awareness of Illness Questionnaire (ITAQ) was scored as either low (≤16) or high (>16). This scale measures awareness that one's various mental health symptoms indicate that the illness is sufficiently serious to require treatment (

22). The physical component summary scale of the 12-item Medical Outcomes Study survey (SF-12 PCS) (

23) measured whether patients had low (≤51) or high (>51) general physical health status at baseline.

Outcome

The outcome was first hospital admission for exacerbation of schizophrenia following randomization while receiving the initial randomized medication as reported by the treating physicians. In the primary analyses, days at risk for hospital admission were limited to the period from baseline to drug discontinuation. Because use of acute care services increases after an antipsychotic is switched (

24), a sensitivity analysis was performed in which hospital admissions within 14 days after medication discontinuation were assigned to the first medication. In an earlier CATIE report (

13), hospital admissions were associated with the first medication for up to 30 days following its discontinuation. Another sensitivity analysis used the annual hospitalization risk (the number of hospitalizations divided by total person-years of exposure) as the outcome instead of first hospital admission.

Analytic plan

The frequency of first-observed inpatient admissions for exacerbations of schizophrenia per 10,000 follow-up days on initially randomized antipsychotic medication was determined overall and stratified by baseline patient characteristics. Observations were censored at medication discontinuation of the assigned antipsychotic or at the end of the first phase, whichever came first.

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression models assessed the strength of associations between each baseline patient characteristic and hazard of first hospital admission. In the adjusted models, each variable of interest was first forced into each model and all baseline covariates were then stepped in with specified entry (p<.15) and retention (p<.05) criteria. Results are presented as hazards ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p values. A sensitivity analysis compared stratified rates of all schizophrenia-related hospitalizations per year of medication exposure as the outcome instead of first hospital admission.

A Poisson regression analysis was used for the sensitivity analysis in which annual hospitalization risk was the dependent variable. Kaplan-Meier curves for each antipsychotic medication group were generated to estimate the survival function to first hospital admission. The log-rank test was used to compare the five medication groups.

Discussion

Outpatients with schizophrenia varied in their risk of hospital admission. During the first phase of the CATIE trial, a recent psychiatric hospital admission, comorbid drug or alcohol use disorder, and severity of positive symptoms at study entry each predicted inpatient psychiatric admission. Similar patterns have been observed among other schizophrenia patient populations (

5,

6,

25). Interventions that successfully reduce use of alcohol and drugs and stabilize symptoms are likely to lower risk of hospital admission among individuals with schizophrenia.

Comorbid alcohol and drug use disorders increased risk of hospital admission to a roughly comparable degree. Comparing bivariate and multivariate regressions further suggests that this risk was largely independent of the effects of baseline symptom severity and global function. Substance use may trigger relapse and hospital admission through the psychoactive effects of the substances themselves (

26) or through their tendency to increase antipsychotic medication nonadherence.

Potential adverse effects of comorbid substance use disorders extend beyond risk of relapse and hospital admission to increased risk of violence, incarceration, and homelessness (

27,

28). Yet despite the high co-occurrence of schizophrenia and substance use disorders, widespread problems persist in the quality of care for patients with both disorders (

29). Providing integrated treatment for this patient population should be a top priority for policy and service system planning (

30).

Low social function at study entry also predicted hospital admission. Previous CATIE analyses (

31) and other research (

32) reveal that social function in schizophrenia is correlated with severity of positive and negative symptoms. Yet comparing the bivariate and multivariate analyses suggests that low social function predicted hospital admission largely independently of baseline positive and negative symptoms. Deficits in social function may increase hospital admission risk by interfering with recruitment of social support or help-seeking behavior during periods of distress (

33). Psychosocial treatments that target social function, such as social skills training, might lower inpatient admission risk by improving function in these areas. In one small clinical trial of social skills training (N=48 in both the experimental and control groups), there was a trend toward lower rates of hospital admission among the experimental group (

34). In general, however, social skills training tends to have smaller, though significant, beneficial effects on distal outcomes, such as relapse, than on proximal outcomes, such as interpersonal living skills and psychosocial function (

35).

Early age of first antipsychotic medication was associated with a greater hazard of psychiatric hospital admission. Schizophrenia starting during childhood or early adolescence tends to be severe and follow a poor long-term course (

36). An association between age of first antipsychotic use and hospital admission risk provides additional evidence for the value of age of onset of disorder for predicting the long-term course of schizophrenia. Tardive dyskinesia also conferred an increased risk of hospital admission, an observation that extended earlier findings indicating that tardive dyskinesia is related to elevated positive symptoms (

37). An association between tardive dyskinesia and hospital admission is also consistent with the concept that tardive dyskinesia increases vulnerability to exacerbations of psychotic symptoms (

38).

In keeping with a previous CATIE report (

13), we found significant differences among antipsychotic medications in time to first inpatient admission. This variability is presumably mediated by differences in the neuroreceptor-binding profiles of the five study drugs. According to one meta-analysis, olanzapine and risperidone, but not quetiapine and ziprasidone, have greater overall efficacy for schizophrenia symptoms than first-generation medications (

39). These differences in overall symptom efficacy among medications are consistent with the risk of hospital admission associated with their use found in this study. These results support the concept that appropriate antipsychotic medication tends to reduce hospital admission through improved symptom control.

Clinical selection of antipsychotic medications should take into consideration not only symptom control but also variation in metabolic effects and other adverse outcomes associated with the different medications. In the CATIE study, clinically significant weight gain was most common among patients assigned to olanzapine followed in descending order by quetiapine, risperidone, perphenazine, and ziprasidone (

13).

Severity of negative symptoms at baseline was not a significant predictor of hospital admission. By contrast, an earlier cross-sectional study of psychotic patients reported that inpatients were more likely than outpatients to have negative symptoms (

11). It is not possible to determine on the basis of this study the extent to which negative symptoms among inpatients are a consequence of rather than a risk factor for inpatient treatment. Understimulation of a hospital environment, excessive use of sedating medications in some inpatient settings, and dysphoria related to institutional restrictions may contribute to the expression of negative symptoms among inpatients.

Although negative symptom severity did not predict hospital admission, it is an important predictor of poor long-term outcome among individuals with schizophrenia (

40). According to one large prospective study, social amotivation was correlated with shorter time to rescue from an experimental, low-dose antipsychotic regimen with supplementary antipsychotic medication (

41).

Poor insight into a need for treatment, which is common among those with schizophrenia (

42), was not a predictor of hospital admission risk. This finding contrasts with previous reports associating low insight with increased risk of inpatient admission (

43,

44). The connection between poor insight and risk of hospital admission is presumably mediated by decreased medication nonadherence (

45). Because the first phase of the CATIE study did not include time following medication discontinuation, the effects of low insight on risk of hospital admission may have been substantially attenuated. This study design feature may also help to explain why unfavorable attitudes toward antipsychotic medication did not predict hospital admission.

This study had several important limitations. First, its design, as mentioned, did not permit assessment of the effects of medication nonadherence, a powerful risk factor for hospital admission (

4). Second, because the analysis was limited to hospital admissions that are related to schizophrenia symptoms, it did not capture other admissions to psychiatric hospitals that were not directly driven by schizophrenia symptoms. Third, because hospital admissions were assessed by clinician report, admissions of which the clinician was unaware were not captured. Fourth, because CATIE systematically excluded persons experiencing a first schizophrenia episode, pregnant or breast-feeding women, and adults with serious and unstable medical conditions, the results cannot be safely extended to these populations. Fifth, the relatively small samples of some strata acted to constrain the power to detect significant group differences. Nonetheless, these limitations exist in the context of a large, well-characterized, and prospectively assessed cohort of adults with schizophrenia.