Bipolar disorder is an illness of chronic and recurrent instability. Mood-stabilizing medications play an essential role in the management of this instability, but they are rarely fully effective by themselves. The addition of a bipolar-specific psychotherapy can help improve outcomes.

Well-studied, bipolar-specific psychotherapies include family-focused therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, group psychoeducation, and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT). A review of 18 trials that incorporated one or more of these psychotherapies supports our contention that they constitute best practices in the management of bipolar disorder (

1).

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) examined the effects of medication management plus family-focused therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, IPSRT, or a brief psychoeducational component. Compared with patients who received the brief psychoeducational component, patients who received one of the psychotherapies had higher recovery rates after one year (51.1% versus 64.4%), and were 1.58 times more likely to be clinically well during any study month (

2). There were no differences in outcome among the three psychotherapeutic modalities. These results suggest that in order to achieve the best outcomes, clinicians who treat patients with bipolar disorder need to consider the use of bipolar-specific psychotherapy. Nevertheless, due to challenges associated with training requirements and reimbursement, psychotherapy is not generally available to patients with bipolar disorder.

In this column, we report pilot testing of MoodChart, an automated, Internet-based program that provides social rhythm therapy, a key element of IPSRT (

3). [The complete report of the pilot study is available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.] The program is fully automated so it can be used by patients who lack access to clinicians with special training. By allowing patients to manage aspects of IPSRT, the Internet application may offer a potential solution to the obstacles limiting more widespread use of psychotherapy in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Social rhythm therapy is based on the hypothesis that mood episodes can be triggered by circadian rhythm disruptions. Therefore patients are encouraged to maintain regularity in the times they perform important daily activities, such as waking up, first contact with another person, starting work (which can include paid work, volunteer work, housework, child care, or school), eating dinner, and going to bed.

MoodChart is a free, open-source program that combines a social rhythm stabilization module with an online implementation of the National Institute of Mental Health Life Chart Methodology (NIMH-LCM) (

4). We chose to focus on social rhythm stabilization because attention to the regularity of daily activities is a common feature of bipolar therapies and because it is well suited for an automated Internet application.

Mood charting was included as part of the therapeutic intervention because it has the potential to increase a patient's understanding of the chronic, relapsing course of bipolar disorder; it also captures a large amount of fine-grained data into a graphic representation that can lead to better communication with a treating clinician and assessment of treatment outcome. We also used changes in the stability of mood, as measured by the NIMH-LCM, as an outcome measure in the pilot study.

The primary weakness of a traditional, paper-based mood chart is that adherence to the charting task is difficult to maintain. MoodChart reduces this problem by sending daily e-mails containing nine embedded links that can be clicked to record the standard NIMH-LCM mood levels. Consequently, recording daily mood is completed with a single click. Users receive multimedia training on selecting the appropriate rating, and each e-mail reinforces accurate ratings by including a brief summary of the rating conventions. Each time the user clicks on a mood rating, a Web page opens to allow patients who are using the social rhythm stabilization module to record the times they perform daily activities. A demonstration of the MoodChart is available at

www.moodchart.org/demo.

Evaluation of MoodChart

A single-arm study evaluated the ability of the automated program to stabilize daily rhythms. The primary outcome measure was change in the social rhythm metric (SRM) over a period of 90 days. The SRM calculates the average number of activities performed each day at more or less the same time (within 45 minutes of a habitual time) over the course of the previous seven days. Scores range from 0, indicating none of the activities are performed at a habitual time on any of the seven days, to 7, indicating all of the activities are performed at the habitual time on each of the seven days.

A secondary analysis addressed the question of whether greater rhythm stability would reduce mood symptoms as measured by the NIMH-LCM. Total symptom burden was defined as the sum of the depression score and the mania score.

Participants were recruited via the Internet by using advertisements that were displayed with bipolar-related searches. The inclusion criteria required participants to report having received a diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder or bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. Participants were required to be at least 18 years old and to have access to an Internet-connected computer.

Before the study began, individuals who registered to use MoodChart were asked to record the times of daily activities during an initial 90-day charting period to select a sample that would be most likely to record the times of daily activities for the duration of the study. More than a thousand individuals registered to use MoodChart and rated their mood for at least one day. Only 64 individuals rated enough days to meet the inclusion criteria. Most participants were women with at least some college education, and the most commonly reported diagnosis was bipolar II disorder. All 64 gave consent to participate in the study.

For the first seven days of the study, participants were asked to record the times of daily activities without attempting to make any changes. On day 8, participants were asked to set target times to perform each activity and attempt to begin the activity within 45 minutes of the chosen time. To help participants track their success, a “hit rate” was calculated and displayed on the participant's mood chart. The hit rate was the percentage of times each activity was performed within 45 minutes of the target time during the past seven days. The study period lasted 90 days.

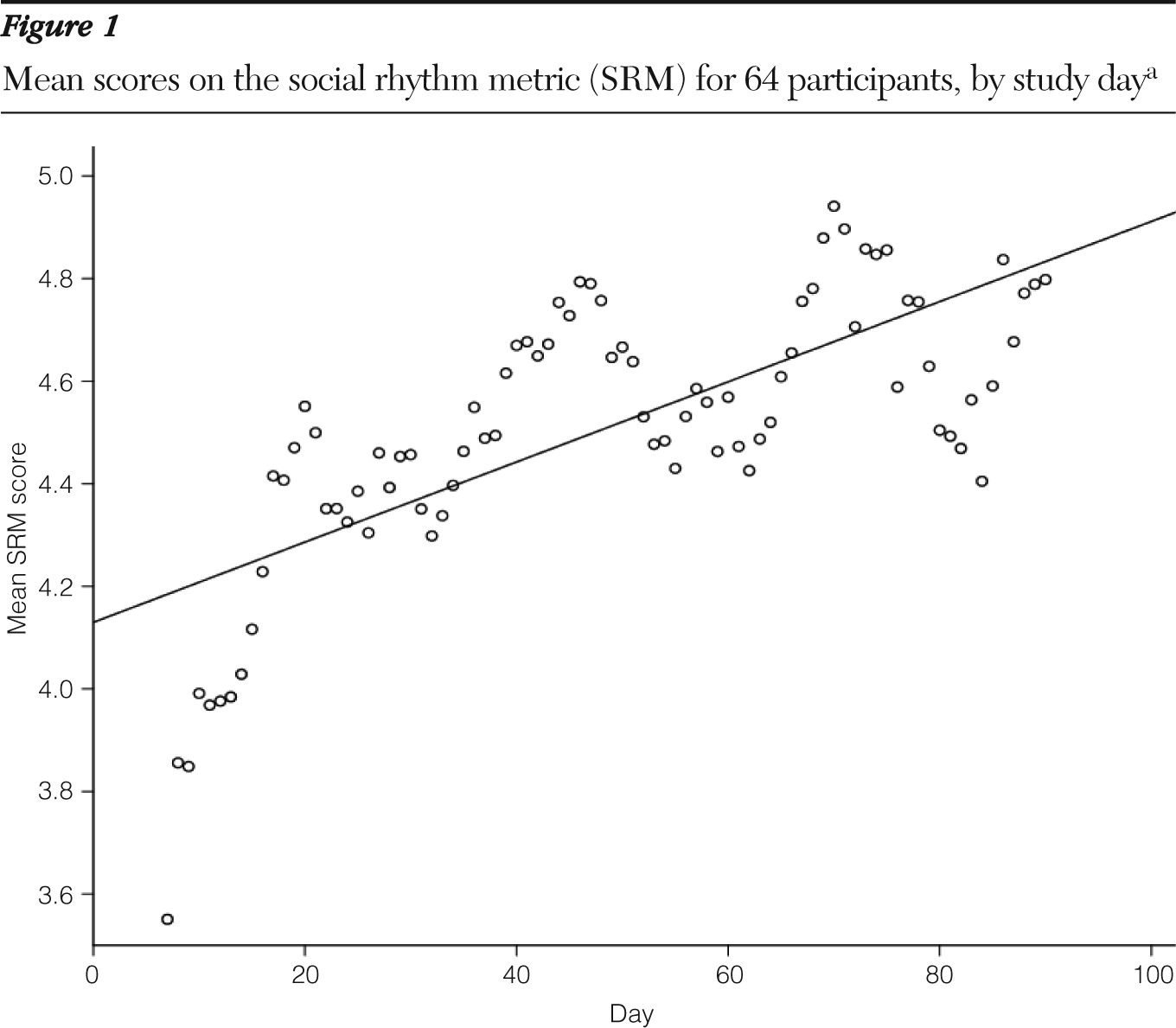

The mean number of days rated was 84 (range 42–90 days). All participants were included in the analysis, which utilized statistical tools tolerant of missing data. The mean SRM was 3.63 at baseline (days 1–7), 4.62 by day 30, and 4.76 by day 90 (

Figure 1). There was also a small but statistically significant inverse correlation between SRM and total symptom burden.

Discussion

Participants using an automated, online adaptation of social rhythm therapy increased their mean SRM by 31% from baseline to the end of the study 90 days later. To put this finding in perspective, one might imagine that a score of 5—indicating that, on average, most activities are performed around their usual times on weekdays but not weekends—could represent a typical score for a healthy person. However a survey of randomly selected people from a university alumni list found a mean SRM of 3.43 (

5). If that finding is representative of a healthy population, an SRM of 4.7 represents a supranormal level of daily-rhythm stability.

Because of the single-arm, open-label design of the study, the results must be viewed as preliminary. Participants were self-selected and were recruited over the Internet. Recording the times of daily activities over an extended period of time takes substantial dedication, even though each rating takes just two or three minutes. Only individuals who rated their mood for 90 days before the study began were offered the chance to participate in the IPSRT module, so the sample was selected to include highly motivated people.

On the other hand, we had no direct contact with participants, and it is possible that clinician involvement and encouragement could allow less motivated patients to complete the program successfully. Anecdotal evidence suggested that the program was valued. Some participants sent e-mails to us reporting that they found it helpful and that their clinicians appreciated seeing the mood charts that they brought with them to their appointments. To increase the generalizability of the results, the study of the IPRST module should include patients who are representative of diverse clinical populations at multiple sites.

Conclusions

The use of a fully automated Internet adaptation of social rhythm stabilization was associated with a 31% increase in the social rhythm metric and a small, though statistically significant, decrease in symptoms of abnormal mood. Because evidence-based, bipolar-specific psychotherapy is difficult for most patients to access, an option that can be provided at almost no cost, regardless of geographic location and time of day, is potentially important. Empirically supported, disease-specific psychotherapy for bipolar disorder represents a best practice, and an automated Internet approach is one way to help clinicians incorporate it into their work.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Dalio Family Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.