Historically, the predominant approach for treating severe mental illness was to place affected individuals in institutions, formerly known as asylums, for lengthy and indeterminate periods. Fortunately, the right combination of economic, civil libertarian, and humanitarian forces, converging with scientific and medical advances, triggered a reformulation of this approach to delivery of services and interventions (

1,

2). The resulting social movement—psychiatric deinstitutionalization—inspired massive efforts to depopulate psychiatric institutions and to shift patients and (to a lesser extent) resources to the community. The trials and tribulations associated with psychiatric deinstitutionalization have been thoroughly documented (

3–

7). The cumulative wisdom from these published accounts is nicely synthesized by the following statement from a 1997 article: “while the concept of deinstitutionalization is sound, its implementation has been flawed” (

1).

Deinstitutionalization refers to a social phenomenon that is much more complex than the popularized portrayals of sudden psychiatric hospital closures and displacement of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. Generally, deinstitutionalization is a multicomponent process involving shifted resources (that is, funding), reduced service capacity of psychiatric hospitals (for example, beds and staffing), increased capacity of general hospitals and alternative facilities to provide psychiatric care, increased capacity of community-based psychiatric services, decentralization of psychiatric services and resources, and reduced reliance on long-term psychiatric hospital care (

4,

8,

9). In theory, a modern mental health system would provide services and supports using methods and settings that are the least restrictive, intensive, expensive, and intrusive. In reality, significant problems were produced by early deinstitutionalization reforms when the contraction of traditional institutional psychiatric care outpaced the expansion of community-based services and supports.

The process of deinstitutionalization has not transpired in a continuous, linear, or uniform fashion. It has been implemented using varying methods and models and has been initiated at different times throughout the mid- to late-20th century (

5,

8–

11). Deinstitutionalization continues to be an ongoing process, as many jurisdictions struggle with realigning their psychiatric hospital systems in environments of vacillating political support, skeptical public opinion, and the practical realities of both building community service capacity and finding alternate accommodations for people with severe and persistent mental illness. An additional factor that complicates recent efforts to close large, antiquated psychiatric hospitals is the overgeneralized declaration that deinstitutionalization is a “disaster” (

7) or a “failed experiment” (

12). Such conclusions may be appropriate characterizations of earlier deinstitutionalization efforts. However, these sentiments persist despite a burgeoning body of evidence that careful implementation of deinstitutionalization policies may thwart potential adverse consequences and may even foster favorable outcomes (

9,

13–

18).

It is generally recognized that a small subset of people with severe and persistent mental illness will continue to require access to tertiary-level, hospital-based psychiatric care (

19,

20). Therefore, moving people into appropriate placements is an integral element of realigning a psychiatric system and may not be considered a negative outcome; rather, it ensures that necessary supports and services are provided to the people who need them. In contrast, transinstitutionalization may be conceptualized as an unintended negative consequence in situations where deinstitutionalization reforms result in people with mental illness finding themselves in institutions that are inappropriate or ill equipped to provide necessary levels of psychiatric care.

The setting for this study was the province of British Columbia. This province is situated on the West Coast of Canada and has a population of approximately 4.4 million that is spread across a massive area of 945,000 square kilometers. Located on the outskirts of British Columbia's largest urban center (Vancouver) is Riverview Hospital, which was established in the early 20th century to serve as central provider of tertiary-level psychiatric inpatient care for the province. In its almost 100-year history, Riverview Hospital has undergone several stages of downsizing, including a reduction from 4,000 to 1,000 beds beginning in the early 1960s and from 1,000 to 500 beds in the early 1990s. These early reforms have been discussed elsewhere (

21,

22) and have been the subject of sharp criticism.

The most recent period of downsizing—the focus of the study presented here—commenced in 2002 with plans to close Riverview Hospital completely. The recent reforms can best be conceptualized as a realignment of the mental health system (

11). This system realignment, which involves hospital depopulation and admission diversion, is consistent with contemporary conceptualizations of deinstitutionalization (

4,

7–

9,

18). Rather than delivering tertiary-level psychiatric inpatient services through one large provincial hospital, the system is being restructured to provide these services in more than 20 regionally based, tertiary-level psychiatric settings that are distributed across the province. A major goal of the system realignment is to move away from a centralized institutional model by supporting regional health authorities in developing sufficient capacity and expertise to meet the needs of community members who require tertiary-level psychiatric inpatient services. The regional tertiary facilities are focused exclusively on persons with severe and persistent mental illness whose service needs exceed the capacity of lower-intensity residential facilities. For each tertiary psychiatric hospital bed that is closed, an equivalent bed is opened in a purposefully built or renovated regional facility, and patients and resources are transferred to that facility. By the end of 2010, Riverview Hospital had fewer than 200 beds remaining, with plans for complete hospital closure by 2012.

The regional facilities continue to provide tertiary-level psychiatric services, but patients receive care in environments that are more “homelike and normalizing” than the isolated, antiquated, institutional setting of Riverview Hospital (

23). For example, the 20 regional tertiary psychiatric facilities are smaller (averaging 15 beds) and more intimate and are designed to be physically more appealing (for example, more natural light), more private (for example, single-occupancy rooms), and better integrated into local communities. Each regional tertiary facility has 24-hour nursing coverage, multidisciplinary care (for example, nursing, psychiatric, and general medical care), and programming that is focused on both clinical and rehabilitative needs. Although some of the facilities are designed to support the long-term care of persons with severe mental illness, others are oriented toward helping patients develop community living skills (for example, preparing meals) so that they can eventually achieve greater independence in less structured environments.

The study presented here examined whether the aforementioned realignment of a provincial tertiary psychiatric hospital system has resulted in a direct shift of individuals to other institutional sectors, such as criminal justice sectors (that is, correctional facilities and forensic psychiatric hospitals) and health sectors (that is, general hospitals and continuing care facilities).

Methods

The study protocols were approved by the research ethics committees of the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, the British Columbia Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission, and Riverview Hospital.

Design

A naturalistic, retrospective, cohort design was used to examine the outcomes of two groups of patients who were discharged from a provincial tertiary psychiatric hospital either before or after the aforementioned system realignment. Administrative data were tracked for two years after each patient's index hospital discharge. The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of service realignment on institutions outside of, rather than within, the tertiary psychiatric system. The dependent variable was an overnight admission to an institution outside of the traditional tertiary psychiatric hospital system. The term “tertiary psychiatric services” is used to describe a level of care that is provided to individuals who have serious, complex, or rare mental disorders (

24–

26). These highly specialized services are beyond the expertise, capacity, or management capability of primary and secondary care services. Access to this level of care usually requires a referral from general psychiatrists or other psychiatric services. Such services are delivered by highly skilled staff who possess advanced training and who have access to specialized resources.

The dependent variables were the number of admissions and length of stay in various institutions: correctional facilities, general hospitals (only admissions that were coded psychiatric), a forensic psychiatric hospital, or continuing care facilities (for example, registered mental health boarding home and nursing home). Although the forensic psychiatric hospital is technically part of the tertiary psychiatric system, it was coded separately for this study because it indicates formal contact with the criminal justice system.

Participants

Participants in this study were patients who were discharged from Riverview Hospital either before (1999–2000) or after (2002–2006) the initiation of the tertiary psychiatric hospital system realignment in 2002. As in similar studies (

27,

28), patients were excluded from this study if they had been discharged from the neuropsychiatry or psychogeriatric units or if their primary diagnosis was dementia or developmental disability. Participants of the two groups were matched on age, sex, length of stay, diagnosis, and level of psychiatric care by using propensity score matching, which uses likelihood scores to determine statistically the extent to which a person in a control group is similar to a person in a study group on the combined matching variables (

29).This method allows for control group members to be found where exact matching is not possible.

Data sources

This study involved a review of data obtained from the computerized administrative databases of three government agencies that oversee corrections, general health, and mental health services in the province. Patient lists with individual identifiers were sent to each of the government agencies, and the data were returned to the research team without identifying information. Participants' sociodemographic information was obtained by reviewing clinical charts maintained by Riverview Hospital. Because of issues of privacy and confidentiality, the data providers prohibited data linkage across the different databases, including third-party linkage of deidentified records, which placed limitations on the data analysis.

Results

Participant characteristics

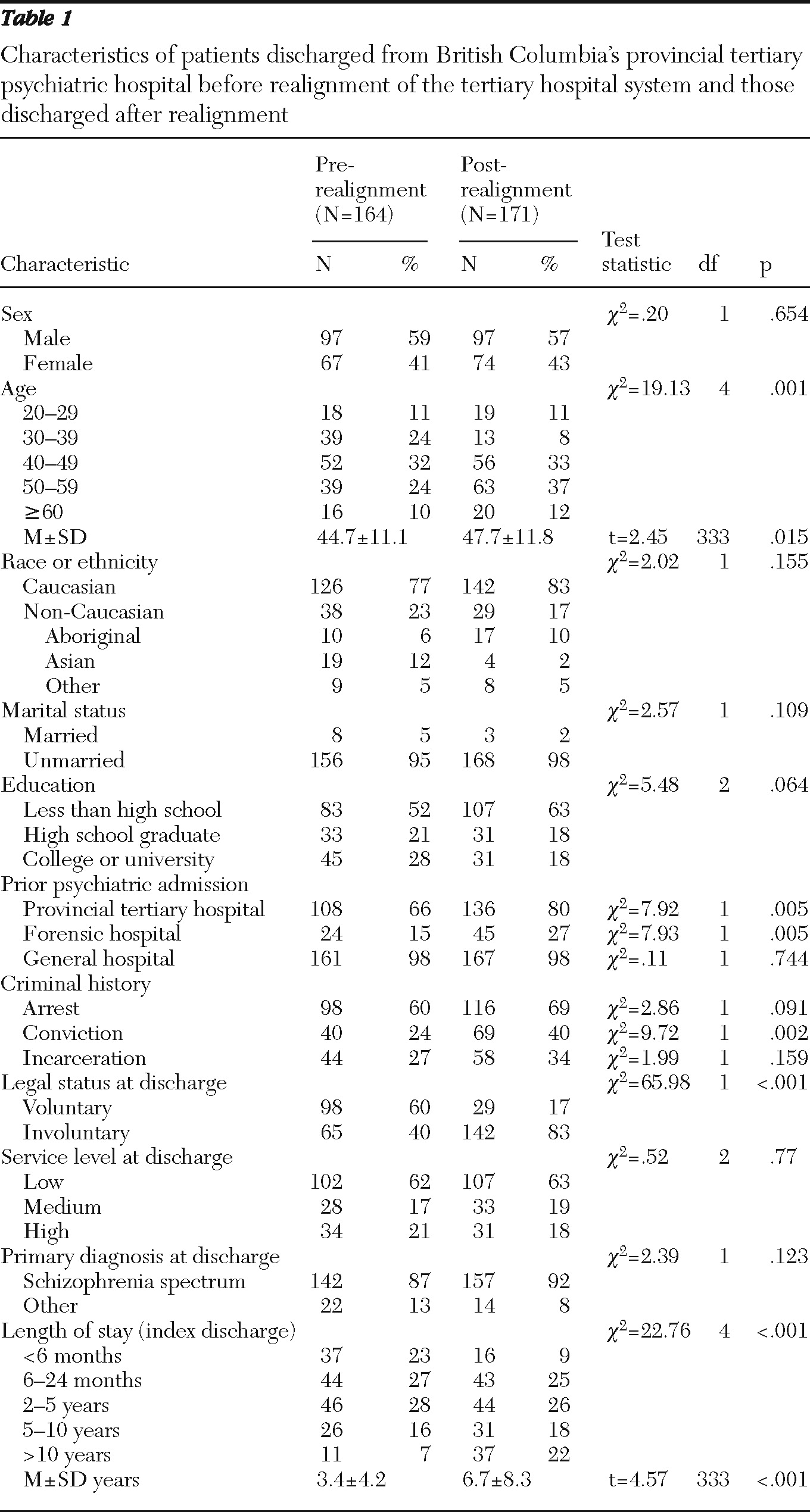

The sample included 164 patients who were discharged before realignment of the tertiary psychiatric hospital system (prerealignment cohort) and 171 patients who were discharged after the initiation of the 2002 system realignment (postrealignment cohort). More than half of the participants were men (N=194, 58%), and most were Caucasian (N=268, 80%). The mean±SD age of participants was 46.2±11.6 years (range=20 to 74 years). Most participants (N=299, 89%) had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Approximately one-third had a history of criminal convictions (N=109, 33%) or had spent time in jail (N=102, 30%). The mean length of stay before the index discharge from the provincial tertiary psychiatric hospital was 5.1±6.8 years (median=three years).

Even though propensity score matching was used to maximize comparability between the two cohorts, they were significantly different on several sociodemographic variables, including age, prior psychiatric hospitalizations, prior criminal convictions, discharge legal status, and length of stay before index discharge (

Table 1). The direction of the between-group differences suggests that the postrealignment cohort may have been more chronically impaired and may have required a relatively higher intensity of tertiary psychiatric care. The planned placements of patients in the prerealignment cohort after their discharge were as follows: private dwelling, 60 patients (37%); community residential facility, 48 patients (29%); continuing care facility, 16 patients (10%); psychiatric hospital or unit, nine patients (6%); and other placement, 31 patients (19%).

Readmission to the tertiary psychiatric hospital

After their index discharge, many participants in both cohorts continued to receive tertiary-level psychiatric inpatient services during the follow-up period. For example, 28 patients (17%) in the prerealignment cohort and seven (4%) in the postrealignment cohort were readmitted to the provincial tertiary psychiatric hospital during the study period. The rate of readmission to the provincial tertiary psychiatric hospital was much higher in the prerealignment cohort (χ2=15.07, df=1, p<.001), which can be attributed to the restructuring of the psychiatric system. All patients in the postrealignment cohort except for one were placed in a regional tertiary psychiatric facility, where many (N=98, 57%) stayed for the duration of the study. Only seven patients (9%) in the postrealignment cohort transitioned to living independently in the community during the study period.

Contacts with the criminal justice system

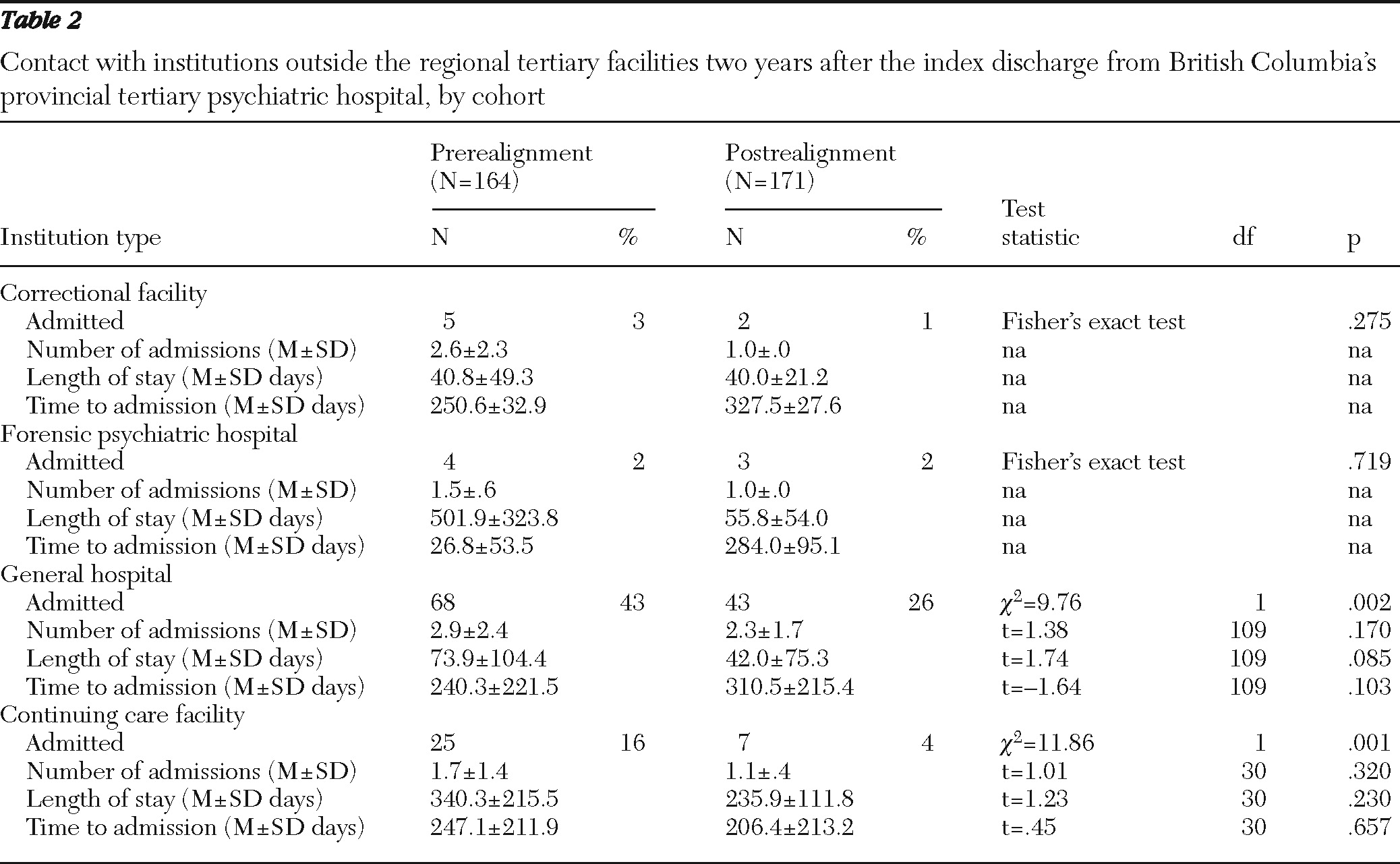

A small number of participants were admitted to institutions in the criminal justice sector during the two-year follow-up. As shown in

Table 2, only five patients in the prerealignment cohort and two in the postrealignment cohort were admitted to a correctional facility, which includes pretrial detention and sentenced incarceration. Similarly, only four patients in the prerealignment cohort and three in the postrealignment cohort were admitted to a forensic psychiatric hospital for court-ordered assessment or treatment purposes. The mean length of stay for all participants was 40.6±41.2 days (median=25 days) in a correctional facility and 310.7±332.0 days (median=118 days) in a forensic psychiatric hospital. The maximum length of stay in a correctional facility during the study period was 105 days. Three patients (2%) in the prerealignment cohort and none of the patients in the postrealignment cohort had long-term stays (more than six months) in a forensic psychiatric hospital after their index discharge. The groups were too small to make meaningful statistical comparisons regarding lengths of stay.

Overnight psychiatric admissions to general hospitals

As shown in

Table 2, overnight psychiatric admissions to general hospitals were common among the participants. A significantly greater proportion of patients were admitted to a general hospital during the study period in the prerealignment cohort (43%) than in the postrealignment cohort (26%). Patients in the prerealignment cohort had a longer mean length of stay in general hospitals than patients in the postrealignment cohort (73.9 days, median=49 days, versus 42.0 days, median=21 days), but this difference did not reach statistical significance. During the study period, five patients (3%) in the prerealignment cohort and two (1%) in the postrealignment cohort had a long-term stay (more than six months) in a general hospital for psychiatric reasons.

Admissions to continuing care facilities

Finally, admissions to continuing care facilities (for example, mental health boarding homes and nursing homes) were significantly more common for patients in the prerealignment cohort than for those in the postrealignment cohort (16% versus 4%) (

Table 2). The mean length of stay for the entire sample was 317.5±200.8 days (median=283 days). After their index discharge, 19 patients (12%) in the prerealignment cohort and four (2%) in the postrealignment cohort had a long-term stay (more than six months) in a continuing care facility. There was no statistical difference between the two groups in the average number of admissions, length of stay, or time to admission to continuing care facilities (

Table 2).

Discussion

In British Columbia, patients leaving Riverview Hospital who continue to require tertiary-level, hospital-based psychiatric services are being relocated to alternative care facilities that are smaller, more homelike, and better tailored to the service needs of each individual (

23). Among the far-reaching implications of hospital downsizing and bed closures, prominent features have been transinstitutionalization and the often closely associated risk of criminalization of people with mental illness, alongside homelessness, poverty, and victimization. These disastrous effects that characterize early psychiatric system reforms have frequently been used as ammunition to assert that community care and deinstitutionalization efforts have failed immeasurably (

12). In fact, the evidence suggests that many of the early efforts to transition persons with mental illness to the community were poorly planned and insufficiently funded and reflected a poor understanding of the realities for people who live with severe and persistent mental illness (

4).

Contrary to the studies that examined early attempts at deinstitutionalization and recent claims that local efforts to reform the tertiary psychiatric system have been a failure, the study presented here found no evidence that regionalizing British Columbia's provincial tertiary psychiatric hospital system has resulted in a significant shift of patients to other institutional sectors. This was examined broadly by exploring contacts with general hospitals, the original tertiary psychiatric hospital, continuing care facilities (for example, registered mental health boarding homes and nursing homes), correctional institutions, and forensic psychiatric facilities. Specifically considered were base rates of admissions, length of stay, and the duration of time between the patient's index hospital discharge and subsequent admissions to institutions in other sectors over a two-year follow-up period. An examination of administrative databases demonstrated that the patients who were leaving Riverview Hospital as a function of the hospital's closure were generally less likely to come into contact with institutions outside of the tertiary psychiatric system than patients who had been discharged previously as part of traditional hospital procedures. The findings suggest that at least within a two-year period, regionalizing large psychiatric institutions can be done in a manner that avoids shifting the burden of care to other institutional sectors.

The results of this study should be considered in light of a number of limitations and caveats. The first limitation concerns the generalizability of the findings. Realignment of the tertiary psychiatric hospital system in British Columbia and the coordinated process of planning for patient relocation may be distinctive and unique. The results are transferrable to jurisdictions that have undertaken similar careful planning processes and have redesigned their tertiary psychiatric hospital system in a similar fashion. Second, we cannot exclude or control for the possibility that sociopolitical factors (for example, changes in community service capacity or other health or criminal justice reforms) beyond those considered in this study influenced the dependent variables. A third limitation of this study is the relatively short duration of the follow-up period. A longer follow-up period may have revealed increased interaction with other institutional sectors by the postrealignment cohort. Fourth, reliance on existing computerized administrative databases has several limitations, such as confining the examination to official institutional contacts, prohibiting the ability to link data across different sectors (for example, health and corrections) and creating some degree of uncertainty regarding the quality and comprehensiveness of the data. A final limitation is that patients in the prerealignment cohort are an imperfect comparison group. Despite use of a propensity score matching technique, patients in the pre- and postrealignment cohorts differed significantly on several central variables (for example, age and length of stay) that are known to be associated with the outcomes of interest. The postrealignment cohort comprised patients who appeared to be more chronically ill.

Conclusions

One of the central questions for evaluating the closure of tertiary psychiatric hospitals is how the transformation of the service delivery system affects persons with mental illness who need tertiary-level care. Findings of this study suggest that the methods and processes used in British Columbia to realign the tertiary psychiatric hospital system have not inadvertently transitioned a tertiary-level psychiatric patient population from one social safety net to another. A larger research program, which complements the study presented here, is continuing to explore the implications of the hospital's closure and the resulting system realignment using methods that provide a more in-depth understanding of how patients' lives are affected or transformed. Indeed, longer-term and more in-depth research that evaluates the impact of mental health policy and system reforms on people with mental illness and their communities is strongly warranted.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Financial support for this study was provided by British Columbia Mental Health and Addiction Services, an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority. The authors are grateful for the skillful support of Derek Lefebvre, Lori Beckstead, Caroline Greaves, and Kimberly Sahlstrom.

The authors report no competing interests.