Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for alcohol and drug misuse can link primary and emergency care with specialty treatment for alcohol and drug use disorders (

1) and may decrease Medicaid expenditures (

2–

4). Clinical trials suggest that screening and brief intervention for alcohol use disorders reduces alcohol use and enhances clinical outcomes (

5). In order to facilitate wider use of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) designated in January 2007 and January 2008, respectively, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for public (that is, Medicaid) and private reimbursement of screening and brief intervention for alcohol and drug use disorders (

6,

7). The billing codes also provide a standardized mechanism for documenting the frequency of particular procedures, the environment in which they took place, and reimbursement rates.

Adoption and tracking of screening and brief intervention are complicated, however, given autonomous state decisions about including the codes in Medicaid fee schedules. Multiple factors influence code adoption choices (including billable procedures, reimbursement rates, state funding, resources, setting or modality, and workforce support and preparation). Differences in definitions and parameters of code options inform adoption as well.

HCPCS codes are divided into two levels. Level 1 HCPCS codes are used primarily by physicians in traditional medical settings. These Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes document a health care procedure that is reimbursable by both public and private insurance. Level 2 HCPCS codes, in this instance “H codes,” are reimbursable only through Medicaid. Private insurance will not reimburse for procedures billed with the alphanumeric codes beginning with the letter H.

Screening and brief intervention procedures identified by HCPCS code H0049 (screening) and H0050 (brief intervention) are reimbursable through Medicaid. Alternatively, CPT codes 99408 and 99409 define procedures of a specific duration. CPT code 99408 is for screenings taking 15–30 minutes, which are reimbursable by private insurance or Medicaid, and 99409 is for screenings lasting more than 30 minutes. State Medicaid plans may choose to adopt CPT codes, H codes, or both. Nonscreening and brief intervention-specific CPT and H codes may also be used for reimbursement of the procedures (

7).

We report information gathered from telephone interviews and e-mail correspondence with state Medicaid representatives about their implementation of AMA- and CMS-designated HCPCS codes for screening and brief intervention for substance use disorders. We also report on confirmatory Web searches of state fee schedules.

Methods

State Medicaid agencies were surveyed in telephone interviews (N=37) or by e-mail (N=7) to assess state approval of screening and of brief intervention reimbursement codes. Respondents' job titles included Medicaid director, chief medical officer, administrator, policy analyst, and program consultant. Six participants were either policy analysts or directors of state agencies other than Medicaid who contributed to writing policy for Medicaid in their state. Web searches of fee schedules corroborated information from states that reported open codes. Web searches of fee schedules also provided data for the remaining seven states (thus there were 51 assessments, including one for the District of Columbia). Interviews occurred between August 2008 and October 2009, and Web investigations were conducted to confirm data from interviews and were completed in July 2010. The institutional review board at Oregon Health and Science University reviewed and approved study procedures.

Interviews included categorical and open-ended questions, and interview duration typically ranged between 20 and 45 minutes. Quantitative data were analyzed with SPSS Version 16 for Windows, and interview transcriptions were coded and analyzed with Atlas.ti, version 5.2. Qualitative analysis began with development of a code list reflecting recurring topics in the transcripts. The code set was tested and revised until consensus on codes was achieved. Three team members coded randomly assigned transcriptions, and two team members served as code auditors, verifying agreement and accuracy of code allocation and suggesting corrections. Narrative material was further reduced by running queries in Atlas.ti and searching for themes to identify specific recurring and compelling points made across the queried material.

Results

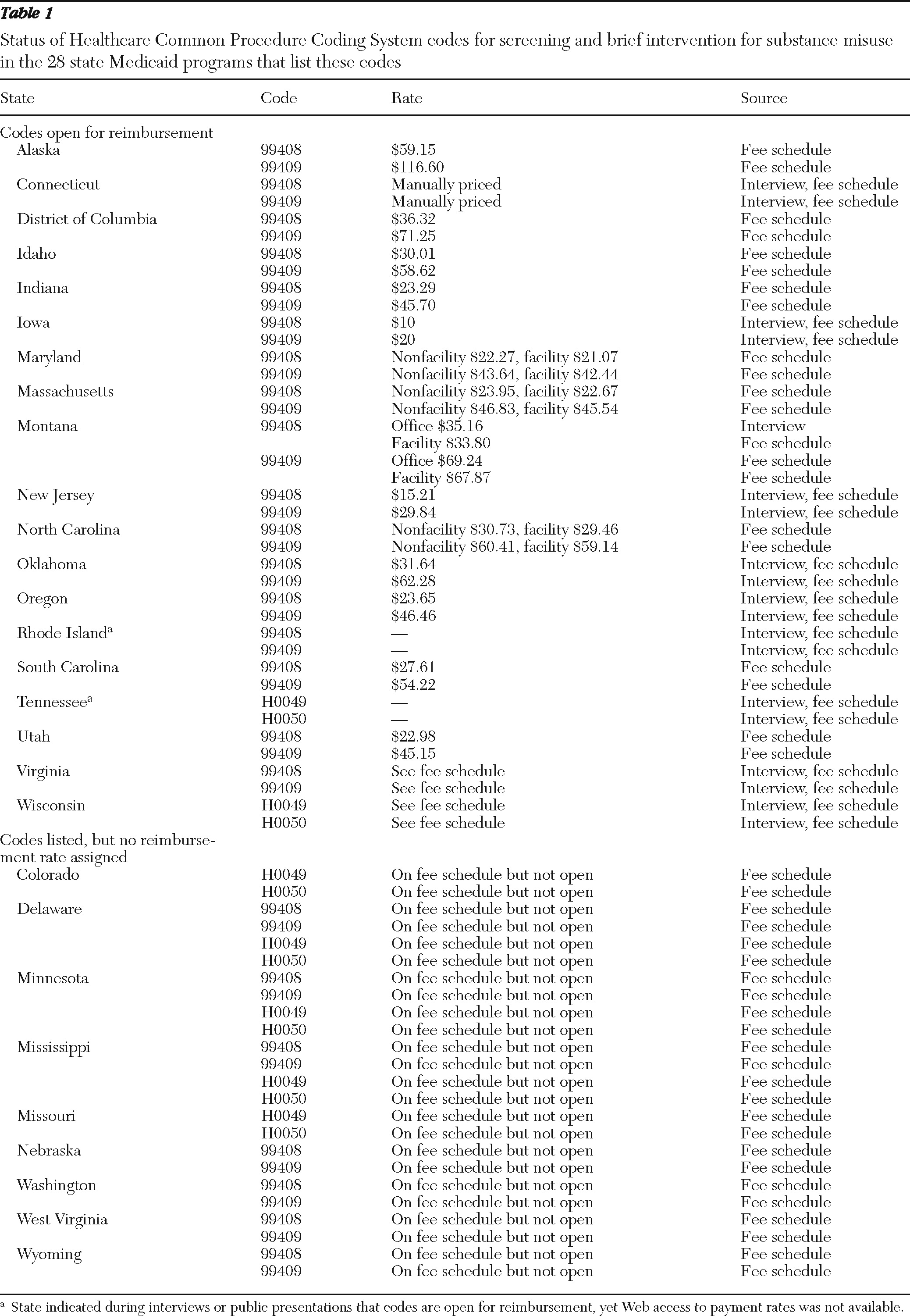

As of July 8, 2010, 28 states listed CMS- and AMA-designated level 1 or level 2 HCPCS codes (or both sets) in their Medicaid fee schedules. Nineteen of those 28 states reimbursed for procedures identified with the HCPCS codes: Alaska, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. States that list the codes in their fee schedule and details regarding reimbursement are shown in

Table 1. [A linked version of

Table 1 is available as an online supplement to this report at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Code choice and reimbursement rates vary. Many states list screening codes, brief intervention codes, or both in their fee schedules but do not include a reimbursement rate. The presence of a code in a fee schedule does not necessarily indicate reimbursement capabilities or implementation. Nearly half of the states (N=23) did not permit Medicaid coverage for screening and brief intervention at the close of data collection.

Three themes from interviews with state Medicaid officials inform the heterogeneity of state decisions on this important policy issue: difficulties with deciding to open codes, concerns over reimbursement rates, and tension over competing priorities in the context of substantial budget cuts. Close examination of these issues can inform access to services, quality of care, client outcomes, and the integration of behavioral health and primary care.

Code choice was a considerable concern, and respondents reported a desire for more guidance about choosing codes. To illustrate, a manager of Medicaid behavioral health services noted, “It's been very confusing why you would use ‘these CPT codes’ versus ‘those CPT codes’ and why you would use a HCPCS code versus a CPT code. There's been no guidance nationally on that, that I can find.” The quote also demonstrates the complexity of HCPCS codes and lack of clarity on differences between level 1 and level 2 codes.

Choices between level 1 and level 2 codes affect the feasibility of certain practitioners conducting screening and brief intervention in particular health care environments. In discussing these matters, a Medicaid policy manager noted, “A community-based substance abuse treatment program might be where the HCPCS codes are more advantageous. But our interest is in developing [a coding system that can be used] in a way that's integrated with the physician's office. I think [the] CPT codes could be used by a variety of practitioners.”

Preexisting formulas dictate reimbursement rates for codes in most states, yet there is some flexibility. As

Table 1 illustrates, rates vary between states, and low reimbursement rates are notable. For example, reimbursement rates range from $20 (Iowa) to $116.60 (Alaska) for code 99409. Some respondents expressed concern that choosing level 1 over level 2 codes or vice versa also meant opting for lower or higher rates, thereby affecting the likelihood of implementation by practitioners. Low reimbursement rates were cited as a reason to not bother with adding the designated codes to fee schedules as well.

Medicaid budgets and state budget cuts were the predominant reasons for not opening codes for screening and brief intervention. In talking about budget challenges, a senior policy analyst for Medicaid summed up the budget issue: “We're trying to actually figure out a way to pay the bills. Most of the stuff we're looking at is cuts, not expansions. Short and simple, no [we won't be opening the codes for screening and brief intervention].”

Discussion

As of July 2010, a total of 28 Medicaid authorities had approved HCPCS codes for screening and brief intervention for substance misuse. However, only 19 of those 28 states had assigned reimbursement rates to those codes. The other nine states simply listed every designated code for every procedure in their fee schedules regardless of coverage. Qualitative analysis of interviews with state Medicaid officials revealed three themes that inform adoption of the CMS and AMA codes: difficulties with choosing codes, implications of varied and low reimbursement rates, and prioritization of competing health care needs in a climate of ever-decreasing resources.

It is noteworthy that interview respondents varied in professional titles and roles and were more or less knowledgeable about specific activities in regard to opening the designated HCPCS codes. Level of knowledge about differences between level 1 (CPT) and level 2 (H) HCPCS codes, allowable procedures, and how code choice would affect which health care settings could perform screening and brief intervention also varied. Therefore, intensive Web searches were conducted to corroborate and add to the data gathered via interviews and e-mail responses.

Designating particular codes for reimbursement of screening and brief intervention provides a mechanism for tracking utilization. However, this type of monitoring is likely complicated by options to bill for screening and brief intervention with preexisting codes, some of which have higher reimbursement rates than are allowed by the CMS- or AMA-approved HCPCS codes. Respondents who articulated this concern often chose to continue using those preexisting codes. Hence, the impact of designating the screening and brief intervention codes remains unclear because procedures may be untraceable as a result of auxiliary code use.

Finally, CPT codes 99408 and 99409 pay more than codes H0049 and H0050. However, they are duration based, with 15 minutes being the least amount of time a practitioner is expected to spend to conduct screening or brief intervention. Two Medicaid director respondents who were physicians questioned the feasibility of adding time to already overbooked medical practices.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate the challenges of using HCPCS codes to promote screening and brief intervention for substance use disorders. The presence of dedicated codes does not necessarily translate to Medicaid coverage for these evidence-based practices, and information gathered in interviews suggests that other codes available to, and used by, practitioners will make tracking implementation of HCPCS codes difficult. Taken together, these findings foreshadow complexities of using billing codes as a policy mechanism for increasing implementation of evidenced-based practices for identifying and treating substance use problems.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant 64378 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Substance Abuse Policy Research Program. The authors thank Dennis McCarty, Ph.D., for his mentorship and generous contributions to this research and report of findings.

The authors report no competing interests.