In the sociological literature “psychological distress” refers to the unpleasant subjective states of mood and malaise associated with depression and anxiety (

1,

2). Feeling sad, hopeless, and worthless and that everything is an effort indicates depression, and feeling tense, restless, and worried indicates anxiety (

3). Sociologists of mental health and illness traditionally use outcome measures from other disciplines, especially psychiatry and psychology; they measure distress by asking questions about depressed and anxious mood and malaise; and they use indexes rather than diagnoses to assess mental health in the community (

4,

5). Levels of psychological distress are directly related to psychosocial functioning, morbidity, and mortality (

6–

10).

Whether people receive effective mental health treatment and how much they receive depends on evaluated and perceived need (for example, severity of the disorder and the degree of social dysfunction), predisposing factors (for example, sex, age, education, and race), and enabling factors (for example, marital status, health plan, and employment status) (

11–

13). Left untreated, mental disorders can cause much unnecessary personal distress, prolonged family burden, preventable disability, and even premature death (

14–

18). Untreated disorders are more likely to become persistent, recurrent, and increasingly severe (

16,

18,

19). Fortunately, prevention and cost-effective treatments are now available for many commonly occurring mental disorders (

14,

20–

22). However, among the 24.6 million adults with serious psychological distress in 2004, only 11.1 million (45%) received treatment for a mental health problem that year (

23,

24). Among those without health insurance, less than 33% received such treatment.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Depression Study reported six-month recovery and remission rates from depression of 50% and 70%, respectively (

25,

26). More recently, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial evaluated depression treatment strategies by comparing four sequential steps of different single medications, medication combinations, or medication with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Only 37% of depressed patients achieved remission after the first step (citalopram only), 67% achieved remission only after all four steps, and only 43% had sustained recovery (

27). STAR*D findings confirm the results of other research that support both the fluctuating and chronic nature of depression and the feasibility of its management (

27–

29).

Psychological, psychopharmacological, and combination treatments for depression can lead to complete and lasting remission, symptom reduction, and better psychosocial functioning (

28–

35). Individuals who achieve recovery or remission enjoy not only decreased disability and improved functioning in work, family, and social situations but also a lowered risk of disease progression and relapse (

33,

34). However, those who only partially or never respond to treatment fail to realize these benefits (

28,

29).

Population-based, state-representative surveillance of the symptoms of commonly occurring

DSM-IV-TR (

36) disorders in the United States began in 2006. State health departments, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration collaborated on implementing the Anxiety and Depression Module that included the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) for the 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (

37). As part of this collaboration, the 2007 BRFSS first included the Kessler-6 (K6) Psychological Distress Scale, designed to measure in population surveys the level of distress and severity associated with psychological symptoms (

38). The 2007 BRFSS also asked a question about receiving medication or treatment for mental health or emotional problems, thereby providing an opportunity to assess the prevalence of psychological distress by treatment status.

The main purpose of this study was to describe the severity and the sociodemographic correlates of psychological distress among adults participating in the 2007 BRFSS who reported receipt of medication or treatment for mental health or emotional problems. An additional purpose was to confirm and extend findings based on the National Comorbidity Survey and its replication that people with more severe illnesses are more likely to be treated (

23,

24,

39).

Methods

The BRFSS is a state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey. The objective of the BRFSS is to collect uniform, state-specific data on health risk behaviors, clinical preventive health practices, and health care access associated with the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States (

40). Each state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and U.S. territories collect data from a representative sample of adults aged 18 years or older, which are then pooled to yield national estimates (

41). BRFSS methods, including the weighting procedure, are described elsewhere (

42). As part of the 2007 BRFSS, trained interviewers administered identical questionnaires about psychological distress over the telephone to an independent probability sample. Although data were available for 202,114 adults in 35 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, this report is based on data from 197,914 participants who answered all of the K6 questions and other variables of interest. All BRFSS questionnaires, data, and reports are available at

www.cdc.gov/brfss.

Psychological distress

The K6 scale was developed in 1992 for the U.S. National Health Interview Survey as a short dimensional measure of nonspecific psychological distress in the past 30 days (

38). The K10, of which the K6 is a subscale, was found to consist of four factors and a two-factor second-order factor structure representing depression and anxiety (

10). The K6 scale identifies individuals who are likely to meet formal definitions for anxiety or depressive disorders as well as individuals with subclinical illness who may not meet these formal criteria (

38). The K6 also strongly predicts the presence of anxiety disorders (for example, agoraphobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder) and minor and major depressive disorders as measured by the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Version 3.0 (

43–

45). Furthermore, the K6 scale is increasingly used in population-based mental health research and has been validated in multiple settings (

38,

46).

Psychological distress was assessed with the K6 scale, which measures how often respondents experienced core symptoms of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder during the 30 days before the interview. This scale asks respondents how often during the past 30 days they felt nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, worthless, so depressed that nothing could cheer them up, and that everything was an effort. These six questions maximize the precision of the scale in detecting cases of serious psychological distress in the context of a short screening battery (

47). The five response categories for each question are none of the time, a little of the time, some of the time, most of the time, and all the time; scoring these response categories from 0 to 4 and summing across the six items yields a scale with a range of 0 to 24. A total K6 score of 13 or greater indicates serious psychological distress in the previous 30 days (

47). A score of 8 to 12 is considered probable mild to moderate psychological distress, and a score of 0 to 7 is considered to indicate no psychological distress (

48). These categories accurately classify respondents into those with either mild to moderate or serious mental illness based on blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

49) as the gold standard. A Global Assessment of Functioning score below 60 indicates serious distress, and higher scores indicate mild to moderate distress (

50).

Control variables

Included as control variables were predisposing factors (age, gender, race-ethnicity, marital status, and education), enabling or impeding factors (income and health care plan), and number (one, two, three, or four or more) of chronic conditions (diabetes, arthritis, asthma, myocardial infarction, heart disease, and stroke) that are known to be associated with receipt of treatment for mental or emotional problems.

Receipt of medication or other treatment

Receipt of medication or other treatment was dichotomously coded (yes or no) on the basis of the question, “Are you now taking medicine or receiving treatment from a doctor or other health professional for any type of mental health condition or emotional problem?” A variable was created combining the three psychological distress categories (serious, mild to moderate, or no psychological distress) and the two treatment levels (yes or no).

Statistical analysis

To account for the complex survey design, all analyses were performed with SPSS, version 14.0. We used its complex samples module, which supports Taylor-series linearization estimation of sampling errors for weighted descriptive statistics, cross-tabulated data, and logistic regression. Further analyses were conducted with SUDAAN, version 9.0. The percentage of respondents was cross-tabulated by sociodemographic characteristics, psychological distress severity level, and the combination of the three psychological distress severity levels and the two treatment levels.

Results

Characteristics of the BRFSS sample

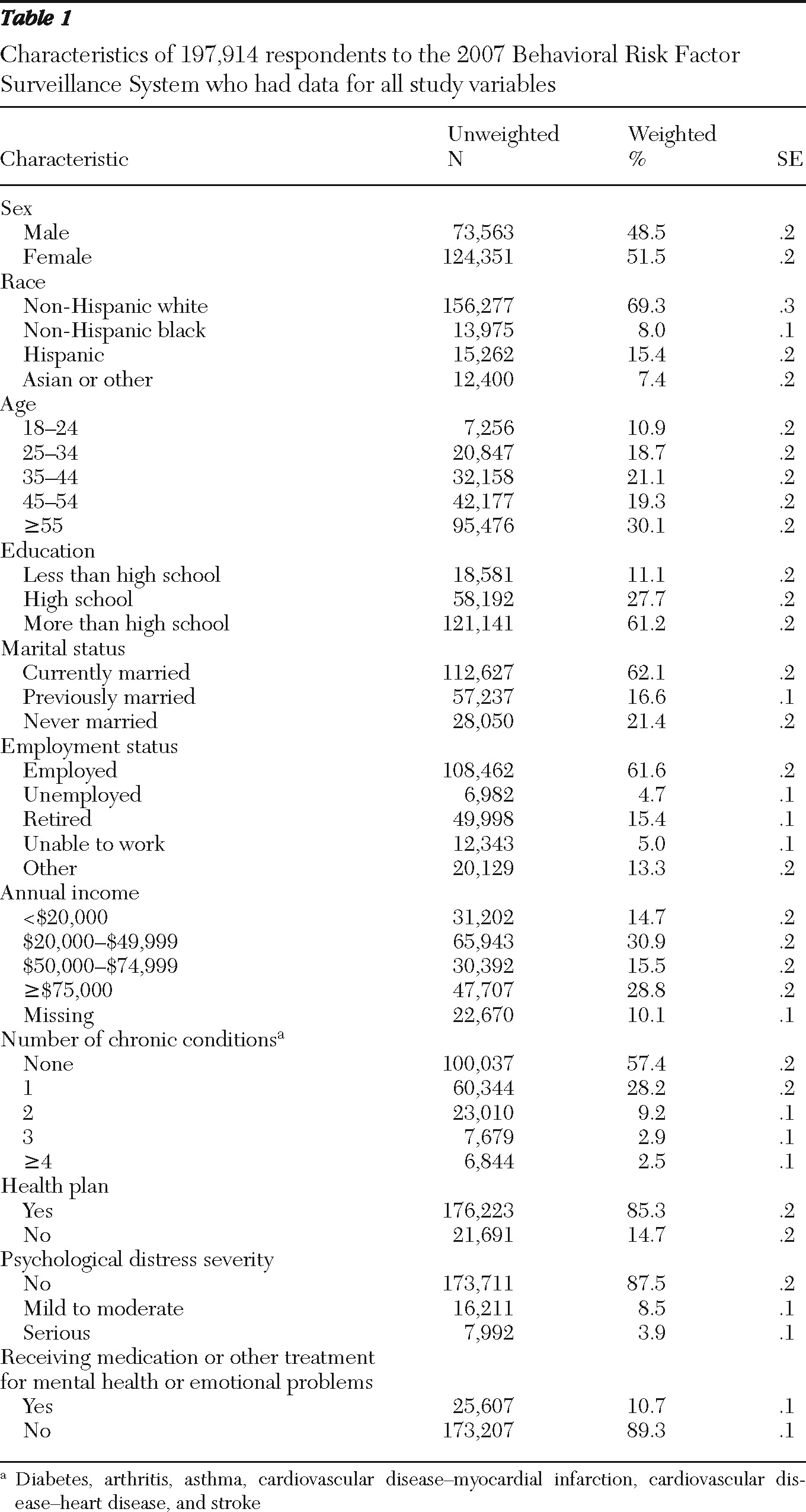

As shown in

Table 1, the BRFFS sample included almost equal proportions (weighted) of women (51%) and men (49%) and persons aged 45 or older (49%) and younger than 45 (51%). Most were non-Hispanic whites (69%), had attended college or were college graduates (61%), and were currently married (62%) and employed (62%). Almost equal proportions reported annual household incomes of ≥$50,000 (44%) and <$50,000 (46%) (10% did not report their incomes). Forty-three percent reported one or more chronic conditions, and 15% reported not having any health plan.

Study sample

In the study sample, 88% had no psychological distress, 9% had mild to moderate psychological distress, and 4% had serious psychological distress (

Table 1). Eleven percent reported receipt of treatment. Among those who reported receipt of treatment, 61% had no psychological distress, 21% had mild to moderate psychological distress, and 17% had serious psychological distress. Among those who reported not receiving treatment, 91% had no psychological distress, 7% had mild to moderate psychological distress, and 2% had serious psychological distress (

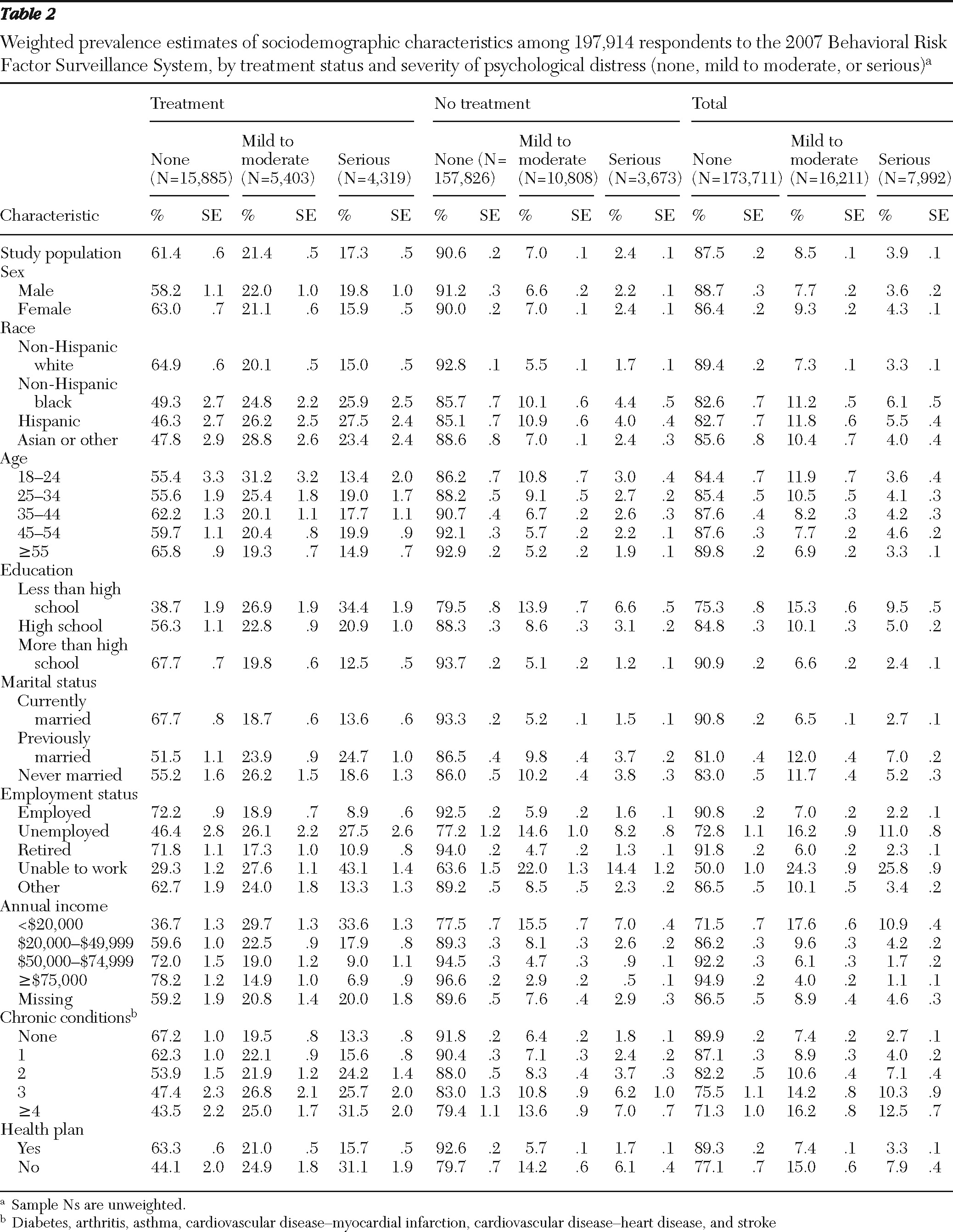

Table 2).

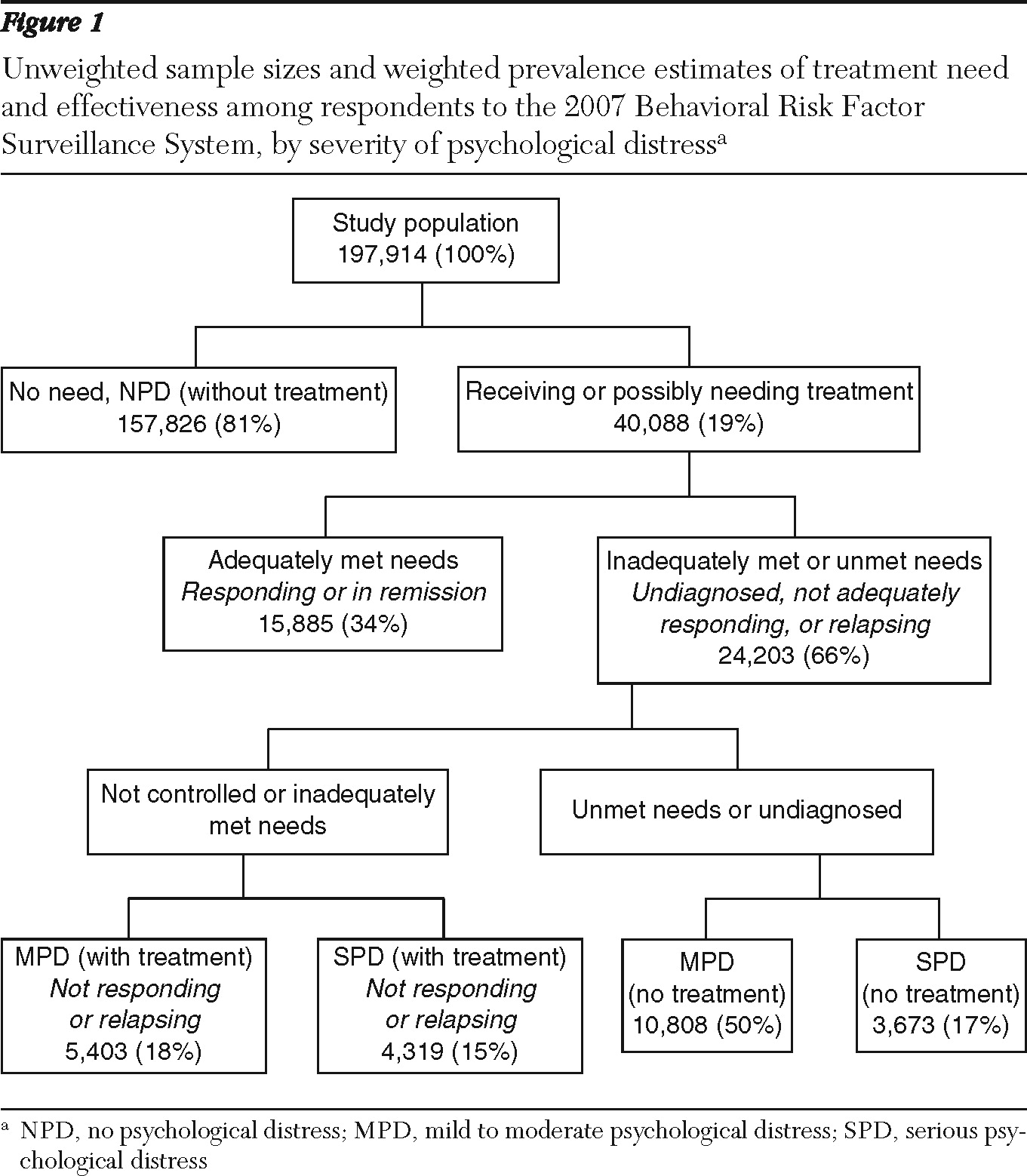

As shown in

Figure 1, 81% of the study sample had no psychological distress and were not receiving treatment for mental health conditions or emotional problems. Among the other 19% of the sample, just over one-third (34%) were receiving treatment and had no psychological distress (that is, they were classified as responding to treatment, in remission, or recovered) (

Figure 1). Of the remaining two-thirds (66%), 50% had symptoms of mild to moderate psychological distress and were not currently receiving treatment (untreated mild to moderate psychological distress), 18% had symptoms of mild to moderate psychological distress and were receiving treatment, 17% had serious psychological distress but were not receiving treatment (untreated serious psychological distress), and 15% had serious psychological distress and were receiving treatment (

Figure 1).

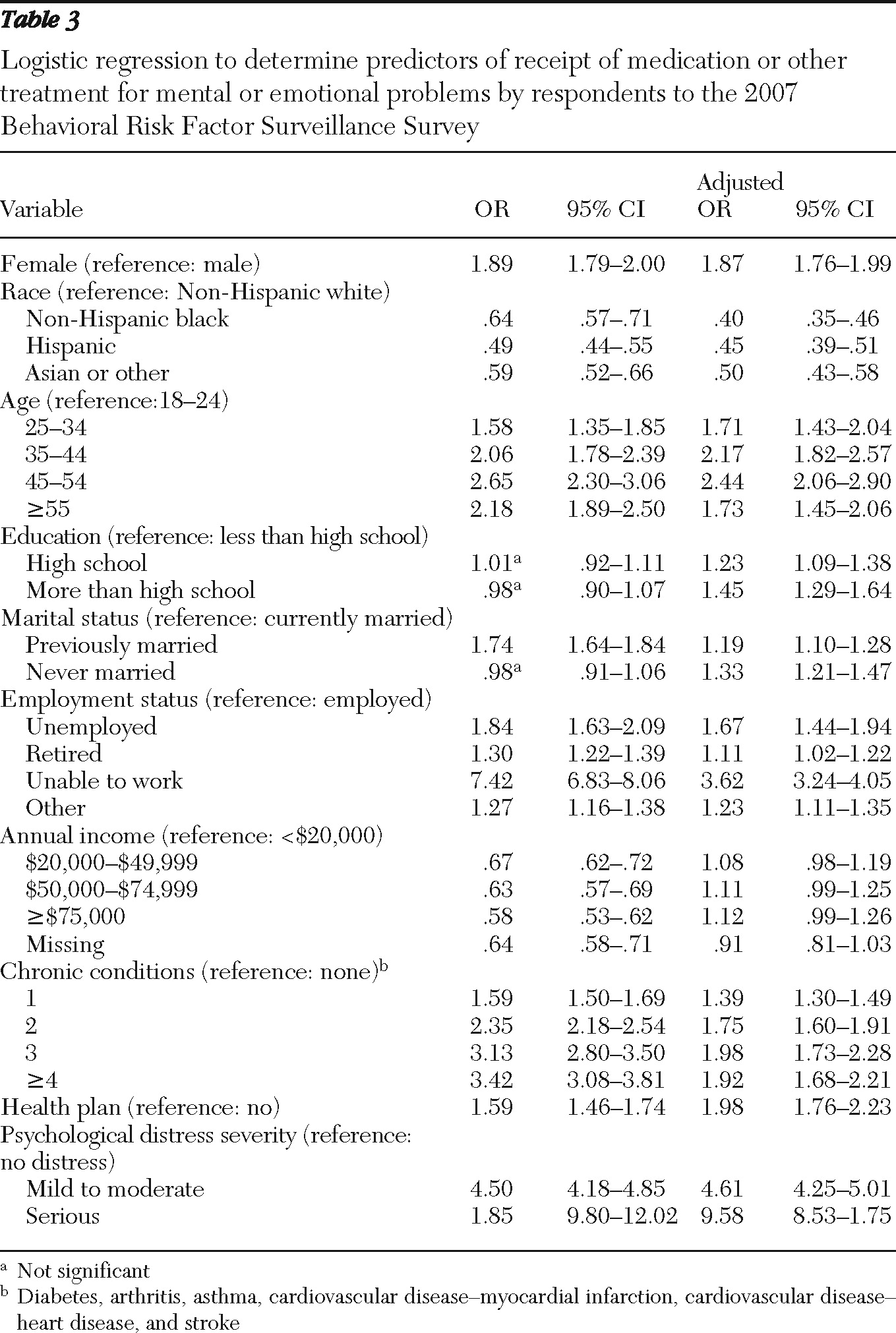

Logistic regression analyses of receipt of treatment

When the analysis controlled for sociodemographic characteristics, the number of chronic conditions, having a health plan, and psychological distress level, the odds of receiving treatment were lower for non-Hispanic blacks (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=.40), Hispanics (AOR=.45), and the group that included Asians and others (AOR=.50), compared with non-Hispanic whites (

Table 3). After the analysis controlled for the same variables, the odds of treatment receipt were higher for women than for men (AOR=1.87); higher for adults aged 45 to 54 (AOR=2.44) than for the youngest group (age 18–24), although not significantly different for the other age groups; higher for adults with only a high school diploma (AOR=1.23) or more than a high school diploma (AOR=1.45) than for those with less than a high school education; higher for those who had never been married (AOR=1.33) or who had previously been married (AOR=1.19) than for those who were currently married; higher for those who were unable to work (AOR=3.62) than for those who were currently employed; higher for those with one or more chronic conditions than for those with no chronic conditions; and twice as high for those with a health plan (AOR=1.98) than for those with no health plan. The odds of receiving treatment increased significantly with psychological distress severity: mild to moderate psychological distress, AOR=4.61; and serious psychological distress, AOR=9.58. However, annual household income did not significantly affect the odds of receiving treatment.

Discussion

Given the fluctuating and the chronic nature of mental health problems, the associated psychological distress, and the feasibility of symptom management (

27,

28), our discussion is framed by the six categories created by combining three psychological distress levels (none, mild to moderate, and serious psychological distress) and two treatment levels (yes and no). Moreover, to set the context for this discussion, we present a brief background for the operationalization of the desirable clinical endpoints of remission and recovery.

More than 25 years ago, the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study first operationalized the desirable clinical endpoints of remission and recovery among persons with depression (

51,

52). Twenty years ago, consensus definitions for applying the concepts of response, remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence of depression were first published (

53). Response refers to a clinically significant reduction in depressive symptoms; remission to the virtual absence of depressive symptoms after a response; recovery to sustained and lasting remission, with or without concurrent treatment; relapse to a return of depressive symptoms after remission; and recurrence to a return of depressive symptoms after recovery (

53). More recently, the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology Task Force recommended a more stringent definition of remission after depression requiring three consecutive weeks during which a patient no longer reports sadness or reduced interest and pleasure and reports two or fewer of the remaining seven

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criterion symptoms (

54).

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first population-based study to describe psychological distress severity and its correlates among persons receiving medication or treatment for mental health or emotional problems. The BRFSS is a cost-effective and timely method of collecting state and local data and often is the only data source available to communities to assess local health conditions and track progress. Studies based on BRFSS data have two overarching limitations. First, only households with land-line telephones are included in the survey sample (those with cell phones only and those without telephones are excluded), and some potential respondents with serious psychological distress may be excluded because they are less likely to answer their telephone. Second, BRFSS data are self-reported and are subject to recall bias and social desirability effects. Because our study is based on cross-sectional data, no causation can be implied. In addition, the 2007 BRFSS questionnaire did not include a question about mental health diagnoses. Thus we were not able to distinguish between diagnosed and undiagnosed conditions in our analysis. Indeed, some of the respondents may not have been aware of their conditions and as a result were not seeking care. Although the 2007 BRFSS lacks specific questions about symptoms, age at onset, episodes (index, frequency, and duration), and treatment (type, duration, and frequency), we feel justified in applying the consensus definitions to our findings and drawing the informed and plausible inferences discussed below, which are consistent with current literature.

Adults in the study population with no psychological distress who were not receiving treatment (81%) may be classified as not needing treatment, whereas the other 19% of the study population may be classified as either receiving or needing treatment (

Figure 1). Of this 19%, the one-third (34%) who had no psychological distress may be categorized as responding to treatment or being in remission and considered to have had their needs met. The other two-thirds (66%) had inadequately met or unmet needs, depending on whether they were currently being treated.

The 18% with mild to moderate psychological distress who were receiving treatment may have been responding to treatment (if they had previously had serious psychological distress), relapsing (if they had previously had no psychological distress), or not responding (if they had previously had mild to moderate psychological distress and were receiving treatment). The 15% with serious psychological distress who were receiving treatment may either have not been responding to treatment (because they continued to have serious psychological distress) or have been relapsing (if they had previously had serious psychological distress and had responded but then reverted into serious psychological distress). The 50% with mild to moderate psychological distress who were not receiving treatment represent persons with untreated mild to moderate psychological distress. Finally, the 17% with serious psychological distress who were not receiving treatment represent those with untreated serious psychological distress (

Figure 1).

Receiving treatment

Our finding that 61% of those who were receiving treatment had no psychological distress (

Table 2) and thus were responding to treatment or in remission is similar to the results of the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study that indicated six-month recovery and remission rates from depression of 50% and 70%, respectively (

25,

26), and from the STAR*D trial that indicated a cumulative remission rate of 67% after all four steps (

27,

28).

Not receiving treatment

Among those with serious psychological distress, our finding that 53.4% did not receive any treatment (data not shown) is consistent with results of studies based on the National Comorbidity Study Replication (

55–

58) and a previous report that used 2007 BRFSS data (

59). Among those not receiving treatment, a larger proportion of women than men had serious psychological distress (2.4% and 2.2%, respectively), but among those receiving treatment, a smaller proportion of women than men had serious psychological distress (15.9% and 19.8%). The odds of receiving treatment were 87% higher for women than for men. Among those not receiving treatment, equal proportions of women and men had no psychological distress, but among those receiving treatment, more women than men had no psychological distress (63.0% and 58.2%, respectively), which may suggest a higher remission rate among women. These better treatment responses among women may reflect more successful treatment outcomes that, in turn, often depend on early diagnosis, receipt of treatment, and better treatment adherence, rates of which may be higher among females and certain sociodemographic groups.

National data on medications used, mental health services received, and unmet needs for mental health services are published periodically (

24,

55,

57). However, the measures used to summarize these data vary widely and leave gaps in our understanding of who is getting treatment, what types of treatment they receive, how long they stay in treatment, how effective the treatment is, and whether treatment affects recurrence or the development of additional mental disorders by preventing, delaying, or reducing the severity of future episodes. The annual population-based, state-level, and small-area (county or metropolitan statistical areas) data necessary to answer some of these questions are not available.

Future directions

Distinct U.S. subpopulations exist by treatment and symptom status. Better understanding of all these groups is essential for improving population-based mental health care. Because surveys that use only symptom screening scales misclassify respondents who are being successfully treated (that is, are responding or in remission or have recovered), it is important to ask additional questions about age at onset, treatment status (duration, frequency, and dosage), and lifetime diagnoses along with a brief validated screen for commonly occurring mental disorders. By using skip patterns in surveys, only a small portion of persons who screen positive (by scoring high on the screener, by reporting a lifetime or current diagnosis, or by reporting past or current treatment) need to be asked a second set of questions that would enable the researchers to determine rates of common mental disorders (for example, mood and anxiety disorders, impulse control disorders, and substance use disorders) and to determine the adequacy and effectiveness of treatment. Adding a call-back survey to the original survey, as has been successfully done for the asthma module in the BRFSS (

www.cdc.gov/asthma/survey/brfss.html#callback), would allow researchers to obtain data on age at onset, childhood adversities, and recent stressful life events that have been implicated in the etiology of commonly occurring mental disorders (

60,

61).

Conclusions

Distinct U.S. subpopulations exist by treatment and symptom status. Better understanding of all these groups is essential for improving population-based mental health care. A three-step strategy would make it both cost-effective and efficient to gather more accurate, detailed, meaningful, and actionable data to inform state and county public health leaders and health care policy makers about these disorders and treatment status.