Gender differences exist along the spectrum of mental health. Women are more likely than men to experience certain mental disorders (depression and anxiety, for example), and these disorders are projected to be the highest cause of disability by 2020 for women (

1–

13). On the other hand, compared with women, men have higher rates of completed suicide (

14) and higher prevalence of alcohol and substance use disorders (

15,

16). Important gender differences also persist in the determinants of mental well-being and resiliency (

17–

19), including employment type (informal or formal) and status (working or not), family status (living with children or not), caregiving roles, education level, and health-related behaviors (

19–

21). Finally, gender differences exist among those who use mental health services. Women use more services, receive more treatment, and have higher rates of hospitalization compared with men (

22).

These gender disparities in mental health highlight the need to include gender equity measures in the process of monitoring population health and mental health systems. Such monitoring can be achieved through the use of health indicators. Health indicators are quantitative or qualitative measures that help in evaluating a process and describing how it changes over time. These measures should be action oriented, allow for regular monitoring of programs, and provide opportunities to guide stakeholders in funding-related decisions and in planning future treatment strategies.

In order to monitor gender inequities in health systems, track gender-related changes in population mental health over time, and evaluate the gender equity of mental health programs and services, gender-sensitive health indicators should be used (

23,

24). Gender-sensitive health indicators are measures that are specific to sex or disaggregated by sex and are stratified by other vital gender-related factors, such as education, income, and marital status. Most mental health programs do not routinely evaluate gender equity in their systems (

25,

26). Because gender differences in mental health exist, the identification of a set of gender-sensitive mental health indicators that include health system indicators (secondary or tertiary prevention) and public health indicators (primary prevention) would be vital to monitoring and evaluation initiatives aimed at reducing gender inequities in mental health and improving the quality of mental health services and programs.

Cross-national comparisons of gender-sensitive mental health indicators would increase our understanding of why gender inequities exist in mental health systems. Gender inequities in mental health exist regardless of a nation's economic development (

27). For example, Latin American countries, such as Chile, Mexico, and Colombia, have all reported greater prevalence of mental disorders among women compared with men, and among women with a disorder, approximately 75% go without treatment (

28–

30). However, before performing such comparisons, researchers must identify gender-sensitive mental health indicators that are feasible to measure and compare on a routine basis across various countries. Although a framework to examine gender inequities in health was proposed in 2003 by the World Health Organization (WHO), no study has attempted to modify or use this framework within the context of mental health.

Using a public health perspective, this study used the WHO framework and applied it to mental health with the aim of identifying a core set of gender-sensitive mental health indicators and assessing the feasibility of measuring and comparing these indicators for a low-, middle-, and high-income country (Peru, Colombia, and Canada, respectively). The three countries were selected because collaborations and data were available.

Methods

Literature review and environmental scan

An environmental scan of reports and manuscripts that contained mental health indicators from a national public health perspective was conducted. The search used performance measurement terms (quality, indicator, evaluation, performance measurement, and monitor), gender terms (gender and sex), and mental health terms (mental illness, mental disorders, depression, and anxiety) in the MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIREME (the Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences), and PsycINFO databases and Google and Google Scholar search engines. Data on potential mental health indicators (definition, label, numerator, denominator, and rationale) were extracted.

Indicator selection

Using the WHO framework, two investigators independently grouped 36 potential mental health indicators (

23) into three tiers (mental health status, determinants of mental health, and mental health systems) (

24) and presented the hierarchical list of indicators to investigators from a broad range of fields (psychiatry, psychology, women's health, public health, and epidemiology) and agencies (governmental, nongovernmental, and academic). Investigators independently ranked the indicators within the tiers using specific criteria, including importance, relevance, feasibility (such as availability to measure), reliability, and being actionable. The ranking results were discussed, and the 18 indicator domains that were ranked as top priority (top 50%) were selected by consensus for inclusion in this study.

Study samples

Peru. Data from the 2002–2004 Epidemiologic Survey of Mental Health, conducted in three urban regions in Peru (metropolitan Lima and Callao; La Sierra-Ayacucho, Cajamarca Huaraz; and La Selva-Iquitos, Pucallpa, Tarapoto), were used for this study. This survey identified 9,881 respondents aged 18 or older via a probabilistic, three-stage random sampling, and it was administered through face-to-face interviews. The survey instruments used to assess the prevalence of mental illness according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) were the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. The response rate was approximately 90% for all three studies. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent, and the studies were approved by the local research ethics board in each region.

Colombia.

Data were from the Colombian National Mental Health Survey (Estudio Nacional de Salud Mental, 2003), a stratified, three-stage, clustered probability sample (

31). The WHO World Mental Health version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI [32]) was administered to men and women aged 18–65 who were noninstitutionalized and who resided in one of five urban regions in Colombia: Bogotí D.C., and the Atlantic, Pacific, Central, and Eastern regions. There were 4,426 respondents from 5,526 households, within 60 municipalities located in 25 departments across the country, resulting in a response rate of 87.7%. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent, and the study was approved by a research ethics board.

Canada.

Data were from the Canadian Community Health Survey on Mental Health and Well-Being, version 1.2, a population-based, multistage, cross-sectional survey conducted in 2001–2002 with men and women 15 years and older living in privately occupied dwellings across ten provinces (N=36,984, response rate of 77%). This survey used components of the WMH-CIDI (

32) to examine the prevalence and correlates of mental disorders and psychological well-being at national, provincial, and regional levels. A detailed description of the methodology has been reported elsewhere (

33).

Sociodemographic factors

Age was categorized into four age groups (29 or younger, 30–44 years, 45–54 years, or 55 years or older). Marital status was categorized as common law or married; separated, widowed, or divorced; or never married or single. Household income was categorized into quartiles. In Peru and Canada, the highest level of education was categorized into the following options: less than secondary (high school), completed secondary, postsecondary (completed or not), or other postsecondary. In Colombia, an option for other postsecondary was not available.

Mental health indicator definitions

Colombia and Canada classified mental disorders according to the

DSM-IV (

34), and Peru used the

ICD-10. Past-year depression was defined as a major depressive episode without a manic episode. Peru reported six-month generalized anxiety disorder, whereas Canada reported 12-month anxiety disorder (endorsing social phobia, agoraphobia, or panic disorder) and Colombia reported 12-month generalized anxiety disorder and anxiety disorder. Because Columbia's 12-month generalized anxiety disorder was not comparable with an anxiety measure from the other two countries, only 12-month anxiety is reported. Self-reported use of mental health services in the past 12 months was defined as use of a psychiatrist, family physician, or other medical doctor; a psychologist; a social worker, counselor, or psychotherapist; a mental health nurse; a religious advisor; or other nonmedical services. In Peru, self-reported use of mental health services was reported, but the reason for use was not specified.

Analysis

An indicator was considered “feasible to measure” if data (2002–2004) were available within the identified databases and “feasible to compare” between countries, meaning that data were harmonized—that is, the indicator had the same numerator, denominator, and diagnostic algorithm and the surveys used the same question and response options. Definitions used for the measurement of the indicators were based on the source documents (

35,

36). The indicators were risk adjusted through direct age standardization by ten-year age groups (

37). Results are reported as percentages stratified by sex and sex ratios (ratio of women to men) and 95% confidence intervals. Results are reported only if they were feasible to measure in at least two countries. The age-standardized indicator estimates were produced by stratifying results by sociodemographic variables in order to explore their influence on sex disparities. All estimates used 12-month time frames unless otherwise specified. Sampling weights were used, and analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2. This project was approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board.

Results

Sociodemographic profiles

Most participants were aged 44 or younger, were married or in a common-law relationship, and had completed secondary school in all countries (

Table 1). In all countries, women were more likely than men to have lower incomes and to be separated, widowed, or divorced. Also, women were less educated than men in Peru and Colombia but not in Canada.

Selection, feasibility, and comparability of indicators

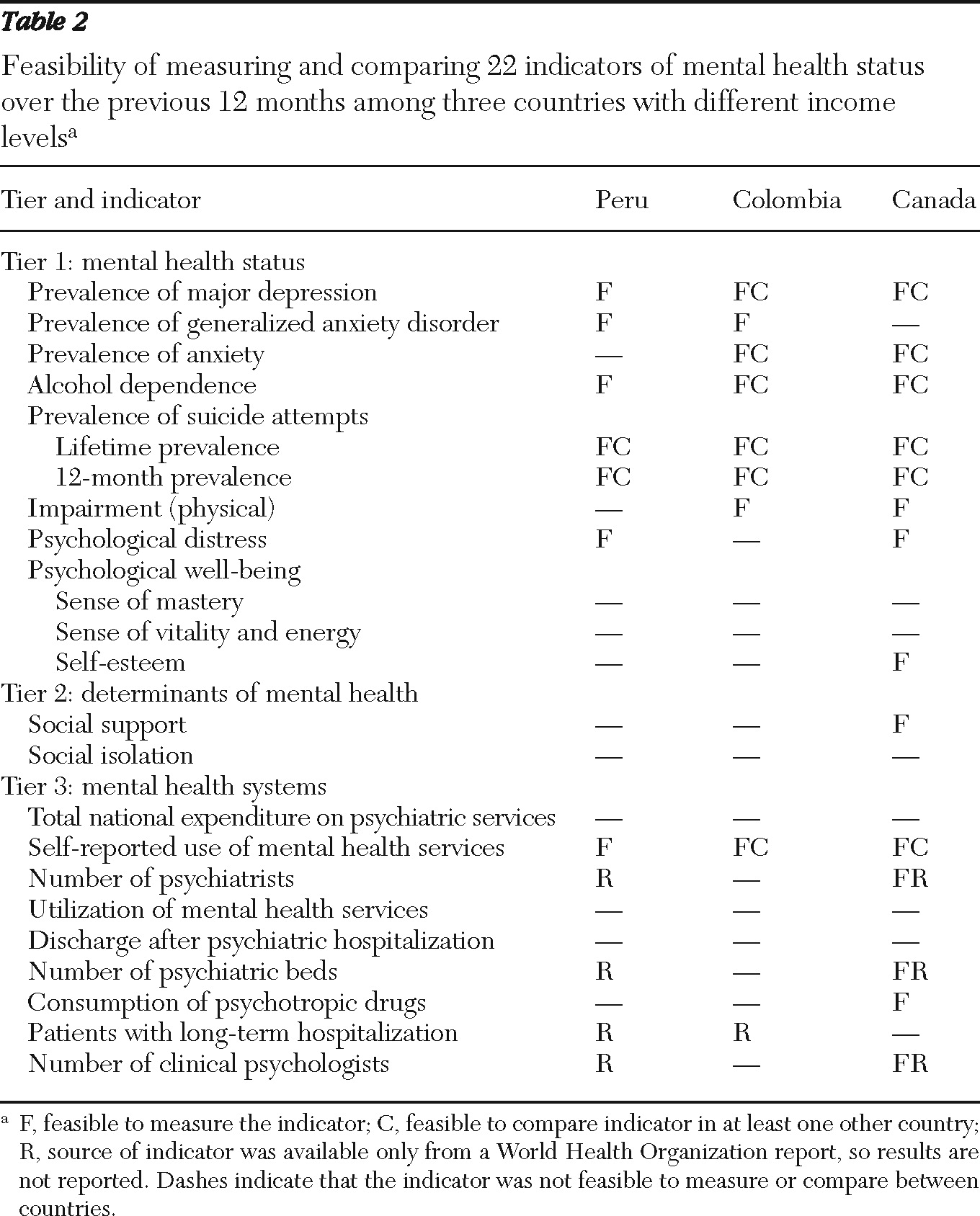

Eighteen mental health indicator domains (22 indicators) were selected for measurement (

Table 2). Most of the indicators in tier 1 measured a mental illness. One focused on physical function (impairment), and another reported on positive mental health (psychological well-being). Whereas psychological distress was feasible to measure in Canada and Peru, different instruments (the K10 distress scale and SRQ-20, respectively) were used and were not comparable. None of the indicators in tier 2 (determinants of mental health) were feasible to measure with available data. Only incidence of suicide attempts (over a person's lifetime and in the past 12 months), a tier 1 indicator, was feasible to measure and compare among all three countries. Indicators that were comparable between Colombia and Canada included 12-month prevalence of depression, anxiety (not generalized anxiety disorder), alcohol dependence, and use of mental health services (

Table 2). Other than self-reported use of mental health services, no indicators from tier 3 were feasible to measure across more than one country.

Gender disparities in mental health

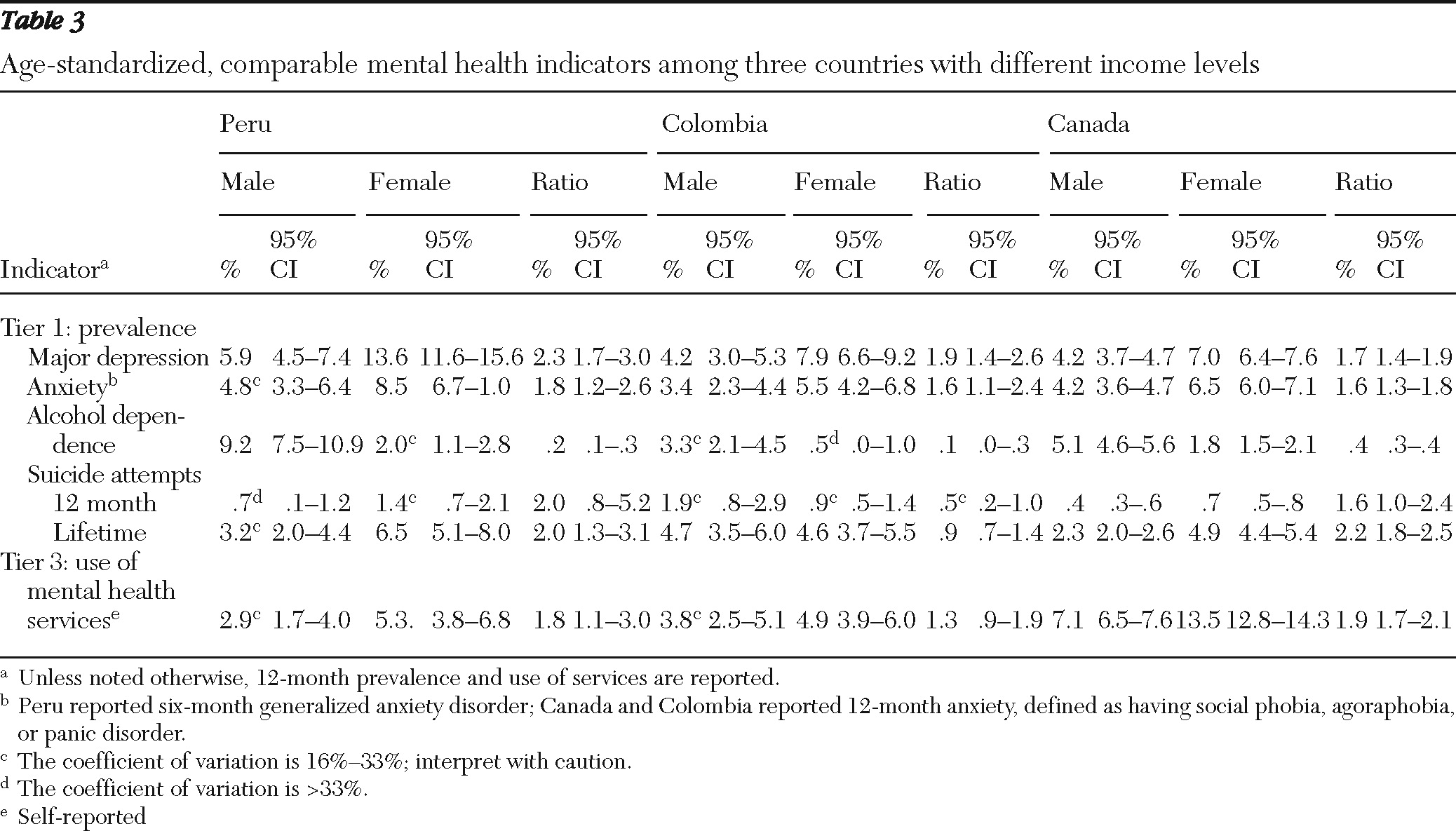

In all three countries, most mental disorders were more prevalent among women than men, with the exception of alcohol dependence (

Table 3). Prevalence of 12-month depression, anxiety, and use of mental health services were almost twice as common among women as men. Although 12-month suicide attempts were more likely among women than men in Peru and Canada, a higher proportion of Colombian men reported 12-month and lifetime suicide attempts compared with women.

Depression was more prevalent among women in Canada than women in Colombia; the proportion of women with anxiety was similar in both countries. Canadian women had less alcohol dependence and were less likely to use mental health services. Compared with Canadian men, Colombian men had similar rates of depression; however, anxiety and alcohol dependence were less prevalent, and service use was lower. A higher proportion of Colombian men reported suicide attempts compared with men in Peru and Canada.

Household income

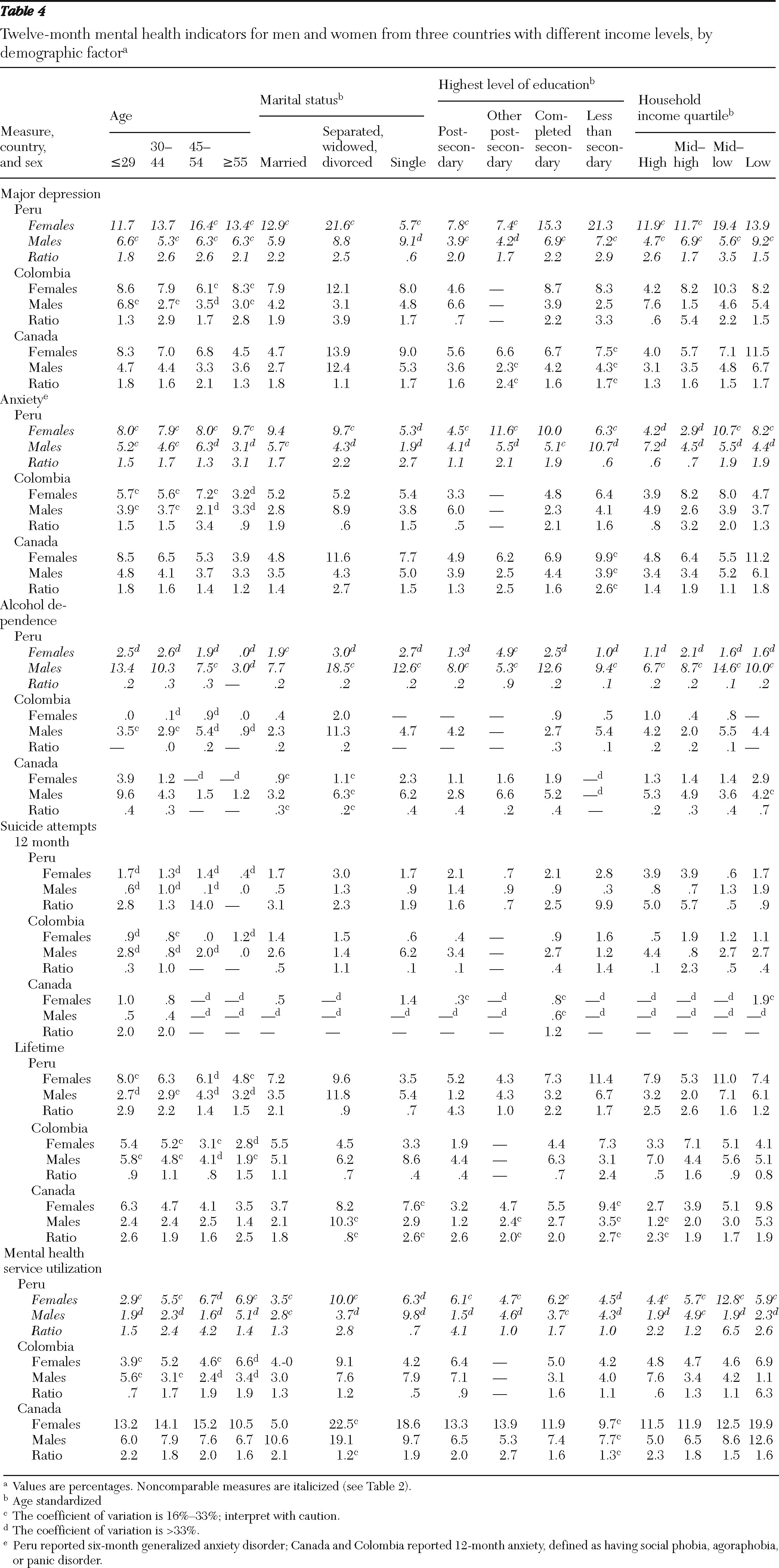

There was a negative relationship between depression and income for men and women in Colombia and Canada (

Table 4). Sex disparities increased as income decreased in Canada; however, in Colombia disparities increased as income increased, affecting a higher proportion of women, except in the highest income quartile, where depression was more common among men than women. Among women in Colombia, those with upper-middle incomes had the highest rates of anxiety and highest gender disparities with their male counterparts, whereas in Canada women in the lowest income quartile had the highest gender disparity and prevalence. Suicide attempts were more common among women than men in Peru and Canada across all income levels, especially in higher income levels. However, in Colombia, the proportions of men and women reporting lifetime suicide attempts were similar, whereas a greater proportion of men reported suicide attempts in the past 12 months. The exception was in the middle-high income quartile, with the highest gender disparity in the highest income quartile. Finally, across all countries, use of mental health services was lowest among low-income men in Colombia and highest among low-income women in Canada; among income groups, the highest disparities occurred in the lowest income quartile in Colombia and the highest income quartile in Canada.

Marital status

Across the marital status groups, the highest rates of mental disorders, including alcohol dependence, were observed among those who were separated, widowed, or divorced, regardless of country (

Table 4). Women who were separated, widowed, or divorced in Canada had the highest rates of depression and anxiety compared with Canadian men and Colombian women. The highest gender gap in the marital status groups was for depression in Colombia and anxiety in Canada among those separated, widowed, or divorced. Anxiety in the past 12 months for this same marital status group was more prevalent among Colombian men than Colombian women.

Lifetime suicide attempts in Peru and Canada were higher among men and women who had been separated, widowed, or divorced compared with married or single men and women. In contrast, single Colombian men had a higher rate of lifetime suicide attempts than single Canadian men and other Colombian men. In Colombia, the proportion of married men making 12-month suicide attempts was nearly twice as high as the proportion of married women. Finally, the proportion of women using health services was consistently higher than the proportion of men regardless of marital status, with the highest rates of use occurring among those who were separated, widowed, or divorced. The proportion of Colombian single men who reported using mental health services was twice as large as the proportion of single Colombian women who used services.

Level of education

Colombian and Canadian women who had completed secondary school or less reported more depression and anxiety compared with women with a postsecondary education or men residing in the same country (

Table 4). In contrast, Colombian men with a postsecondary education had more depression and anxiety than men with a lower level of education. Canadian men with a lower level of education (secondary school or less) reported more depression than men with higher levels of education. Levels of anxiety were similar across all levels of education in Canada with the exception of other postsecondary education (

Table 4). Sex disparities in depression and anxiety prevalence in Peru and Canada were reduced as education level increased, which paralleled the decrease in prevalence among women as education levels increased. Yet in Colombia, with more education depression and anxiety became more prevalent among men than women. The highest use of health services was observed among men and women with postsecondary education or other postsecondary education in Colombia and Canada and secondary education in Peru. In Canada, the highest sex disparity was observed among men and women with an “other postsecondary” level of education.

Discussion

It is feasible to assess gender equity in mental health systems by using gender-sensitive mental health indicators within and across countries. This study provides empirical evidence that can be used to support the development of public health programs that monitor gender equity in these systems. Although there is a data gap concerning the determinants of mental health (tier 2) and mental health systems (tier 3) in all countries, a third of the indicators were comparable between two countries, and one indicator was comparable among all three countries. Once sociodemographic factors were considered, sex disparities in the gender-sensitive mental health indicators identified several groups at risk of poor mental health in all three countries, which is vital information for program planners and policy makers.

A key finding of this study was that most selected indicators, particularly in tiers 2 and 3, were not feasible to measure in all countries. Although many individual health institutions had available data for tier 3 indicators, they were either inaccessible or could not be pooled. These challenges are important to consider in the development of future cross-national programs aimed at monitoring and improving mental health systems. These results may provide the empirical evidence needed to support a larger pilot study aimed at measuring, through standardized primary data collection from several institutions, a few indicators considered to be able to have a high impact on policy in reducing gender inequities in mental health across several countries. Such a study should also focus on the cost-effectiveness of implementing the routine use of these indicators.

This study found that cross-national comparisons of gender-sensitive mental health indicators were feasible, yet there were several limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. These include vast differences in samples (including differences in the proportions of rural and urban respondents) and sample sizes (resulting in a high coefficient of variation for the 12-month estimate), sources of data (survey or administrative), lack of information on the measurement equivalence of the indicators, lack of risk adjustments other than for age, and increased variability between countries in terms of their economies, social norms, cultures, politics, ecology, and biology. In order to ensure comparability, this study obtained good-quality, harmonized data from three countries to populate as many of the selected indicators as possible. The data sources were restricted to data sets from a population-based survey from all countries, where the majority of participants were obtained from urban centers. Although the measurement equivalence of the indicators is unknown, the CIDI was primarily used and has been validated cross-nationally. The availability of comparable cross-national data allows for more rapid policy development aimed at decreasing gender inequities in mental health. Future studies should aim to select and validate a core set of mental health indicators in other countries that include similar samples and can be measured routinely so that they can directly feed into a country's health policy.

One of the benefits of performing cross-national comparisons was the evidence that emerged concerning suicide attempts. Colombia had no sex disparities in the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts, but a higher proportion of men reported suicide attempts in the past 12 months. In contrast, the opposite results were found in Peru and Canada, which were more consistent with previous literature (

29,

38–

40). These findings suggest that Colombian men are at higher risk of developing a mental illness than men from Peru and Canada, which may be due to increased exposure of Colombian men to kidnappings, threat, conflict, and violence compared with Colombian women (

41,

42). This example reflects some of the potential benefits of making cross-national comparisons as well as the limitations of comparing such estimates.

The use of sociodemographic factors was vital in assessing gender-sensitive mental health indicators because large gender inequities were found, and these may aid in identifying groups at particular risk of mental illness. For example, examining gender equity in mental health by marital status showed that men and women who were separated, widowed, or divorced were at increased risk of developing a mental illness. Depression was most prevalent among women in this category, and men and women in this group had the highest rates of mental health service use. Men in this group reported the highest prevalence of alcohol dependence. These findings are consistent with previous literature, in which separated, widowed, or divorced women were shown to be at higher risk of depression, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders, and both men and women in this group used more mental health services than individuals who were never married or married (

43–

48). Future studies should further explore the impact of examining gender-sensitive mental health indicators by sociodemographic factors and assess whether they can serve to further identify new high-risk groups; between-country variability in sociodemographic factors may also help explain the between-country variations.

This study has inherent limitations beyond those already mentioned. Data availability limited the measurement to outcome indicators instead of structural or process indicators. In particular, no indicators in tier 2 were feasible to measure, and few were available and comparable in tier 3. Variability in sampling strategies also resulted in data that were more generalizable to urban populations because only Canada included rural participants. This variability limited the monitoring of gender equity in population mental well-being and the evaluation of equity in public health services and health resources, such as the allocation and uptake of health services. Cross-national variability among the few comparable indicators could not be adequately investigated by other factors that may affect gender equity in mental health, such as cohort effects, language, culture, religion, ecology, history, economy, or policies.

Conclusions

Measuring a core set of gender-sensitive mental health indicators on a routine basis would be useful for policy makers and program planners in identifying communities at high risk of gender inequities in mental health, monitoring equity in mental health systems, reducing avoidable gender disparities in health system processes, and highlighting opportunities for improvement. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that it is feasible to select, measure, and compare gender-sensitive mental health indicators cross-nationally. Further studies should consider the cost-effectiveness of including gender-sensitive mental health indicators as part of a routine evaluation of mental health systems.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant NIG-79774A from the Institute of Gender and Health of the Canadian Institute of Health Research.

The authors report no competing interests.