Serious mental illness is associated with high rates of co-occurring substance use disorders. With the lifetime rate of alcohol or drug use disorders in the general population around 17%, overall lifetime prevalence among people with serious mental illness is about 50% (

1). Clients with co-occurring disorders need integrated services for co-occurring disorders (

2). In addition, employment provides a meaningful activity that supports recovery (

3).

Supported employment helps people with serious mental illnesses to obtain competitive jobs aligned with their preferences and provides ongoing, individualized supports (

4). The competitive employment rate for individuals who receive supported employment is more than twice that of those enrolled in other kinds of vocational programs (

4). Moreover, supported employment is more effective than other vocational models for persons with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics, including substance use disorders (

5,

6).

Most clients express the desire to work (

7). Unfortunately, access to vocational services is difficult for individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders. Exclusion from vocational services because of substance use is common despite equivalent employment outcomes among those with and without co-occurring disorders (

8). Practitioners often identify drug and alcohol use as the major barrier to employment and may not refer clients with co-occurring disorders to vocational services (

9). This study explored enrollment in supported employment among clients with and without co-occurring substance use disorders. We hypothesized that clients with co-occurring substance use disorders, compared with those with serious mental illness alone, would be less likely to become enrolled in supported employment.

Methods

This historical cohort study examined the relationship between co-occurring disorders and enrollment in supported employment services among clients with serious mental illness. The study was conducted at Thresholds Psychiatric Rehabilitation Centers in Chicago, an agency that provides a comprehensive array of mental health and rehabilitation services for individuals with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder. Employment specialists at Thresholds are embedded within clinical mental health treatment teams and provide services at multiple program sites in the agency. The Thresholds Institutional Review Board approved the study.

The study group included 1,748 clients consecutively admitted to Thresholds services between January 2008 and December 2009.

Mental disorders, including substance use disorders, were based on criteria in the DSM-IV-TR. Sociodemographic information and employment history and interest were based on self-report. Employment history and employment status at intake included any kind of employment, both competitive and noncompetitive. The primary outcome measure, enrollment in supported employment, was determined by assignment to an employment specialist during the study period. We also assessed interest in employment at intake and success once enrolled.

Information about mental health and service utilization was culled from the electronic medical record and included diagnoses of mental disorders. Psychiatrists and other licensed professionals determined presence of active substance use disorders according to DSM-IV-TR criteria. We used the most current diagnosis of substance use disorder entered in the electronic medical record at time of data collection. Direct service staff conducted mental health assessments with all Thresholds clients at intake and obtained information from new clients on age, race, years of education completed, employment history, interest in employment services, current employment status, residential status, and receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), or both. Employment specialists documented supported employment service utilization and outcomes. Only competitive employment outcomes achieved by those enrolled in supported employment services were included in the analysis.

Using SPSS version 15.0, we imported data from the electronic medical record for analysis. We examined continuous variables for normality of the distributions and outliers and removed less than 5% of the clients from analysis due to outliers indicative of data entry error or missing data. We used t tests and chi square analyses to compare groups (active substance use versus no substance use) on demographic and clinical characteristics and employment services utilization. We conducted bivariate analyses comparing enrollment in supported employment with demographic, clinical receipt of benefits and employment variables. We also conducted logistic regression analyses to examine the relationship between the dichotomous dependent variable “enrollment in supported employment” and substance use, race, diagnosis, entitlement benefit, and homelessness status.

Results

Of 1,748 clients, 595 (34%) were diagnosed as having an active co-occurring substance use disorder. Clients with and without a co-occurring substance use disorder were similar in employment status at intake. Individuals with a co-occurring disorder were more likely than those without one to be older (t=–2.26, df=1,746, p=.02), male (χ2=34.24, df=1, p<.001), African American (χ2=39.67, df=1, p<.001), homeless at intake (χ2=69.27, df=1, p<.001), less educated (t=5.65, df=1,530, p<.001), and without SSI or SSDI benefits (χ2=54.34, df=1, p<.001).

At admission, 445 (75%) of 595 clients with a substance use disorder expressed an interest in supported employment compared with 810 (70%) of 1,153 clients without a substance use disorder (χ2=4.29, df=1, p=.04). Nevertheless, among those expressing an interest in employment (either at admission or later), clients with a substance use disorder were less likely to enter employment services (63 of 452, 14%, versus 292 of 844, 35%; χ2=63.17, df=1, p<.001). Among those who enrolled in supported employment, the competitive employment outcomes were similar for the two groups (16 of 63, 25%, for those with co-occurring disorders; 82 of 292, 28% for those without). The two groups obtaining competitive employment did not differ on days employed, earnings, hours worked per week, or days to first job.

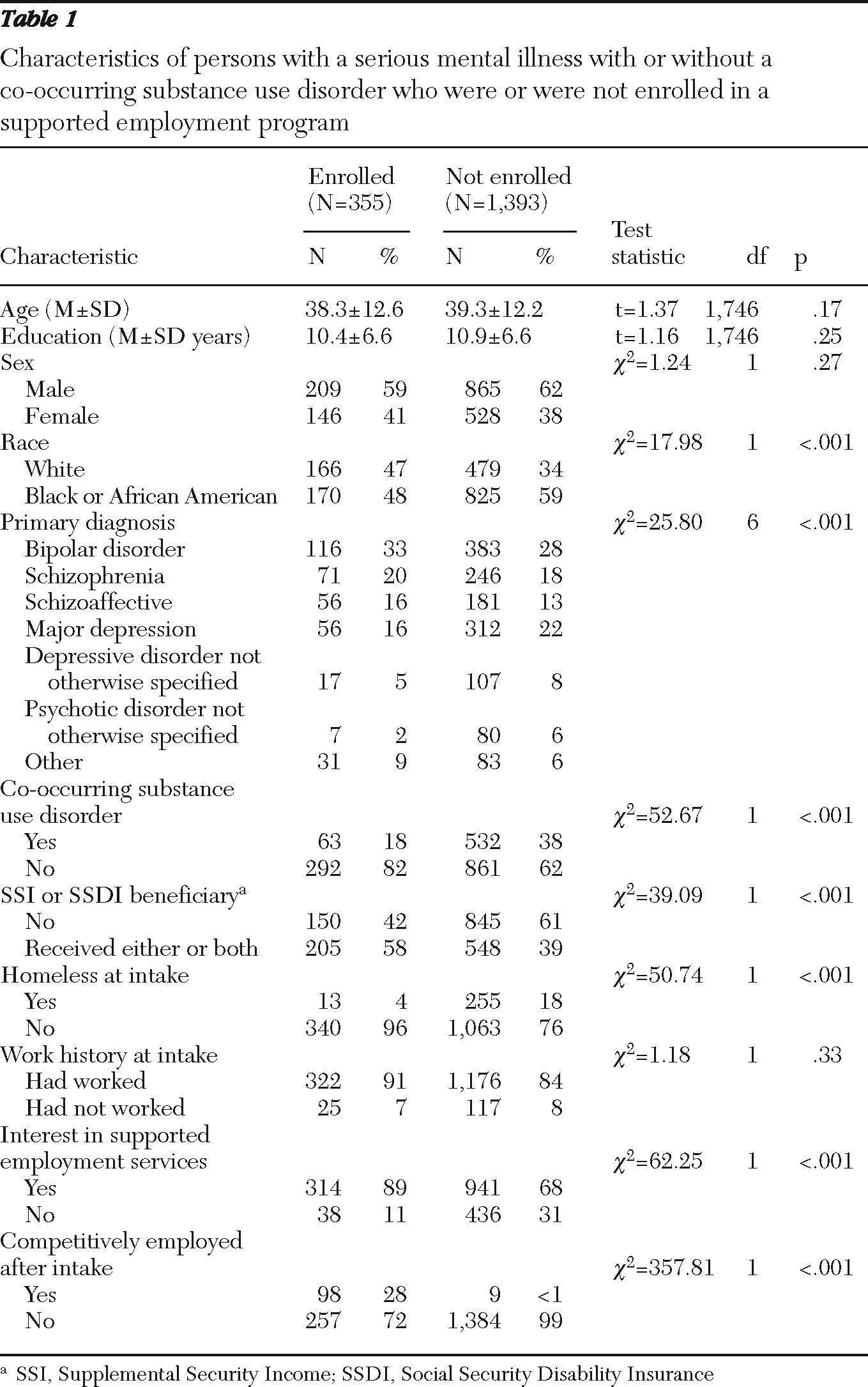

As shown in

Table 1, clients were less likely to become enrolled in supported employment if they had substance use disorders, were African American, were homeless at intake, did not have SSI or SSDI, or had a diagnosis of unipolar major depression.

Results of the logistic regression model showed that the overall model was statistically significant (χ2=114.65, df=7, N=1,748, p<.001) and correctly classified 78.4% of the cases. When included in the overall logistic regression model, three of the five variables significantly predicted enrollment in supported employment. Participants with a substance use disorder were 52% less likely to be enrolled in supported employment (B=−.74, SE=.16). Those with entitlement income were 65% more likely than nonbeneficiaries to be enrolled (B=.50, SE=.13), and participants who were homeless at intake were 79% less likely to be enrolled in supported employment (B=−1.54, SE=.30). Axis I diagnosis (B=.02, SE=.04) and race (B=−.13, SE=.11) did not predict enrollment.

Discussion

Despite high expressed interest in employment services, clients with a co-occurring substance use disorder were less likely to become enrolled in supported employment. Several explanations are possible. Practitioners may delay referrals because of competing priorities, such as finding clients a place to live (

10), because they question their clients' readiness, or because they wish to use employment to reward success in substance abuse treatment (

11). Practical realities of state funding and policy climates also affect referrals. The federal-state rehabilitation system is underfunded, and vocational rehabilitation counselors are pressured to prioritize services for clients with less complex challenges. Clients with co-occurring substance use disorders may doubt their ability to secure employment and delay participation for fear of failure and self-stigma (

12).

Among clients who entered a supported employment program, employment outcomes were comparable for those with and without co-occurring disorders. Substance use may not substantially affect vocational functioning more than serious mental illness alone does. Alternatively, individuals with co-occurring disorders may have better vocational skills or greater motivation to succeed in work than those with a serious mental illness alone (

8). In either case, selection bias may contribute to comparable employment outcomes. Whether the discrepancy in enrollment in services is a result of practitioner bias, client hesitancy, or a combination of the two, a much more select group of individuals with co-occurring disorders enter supported employment than those without such a disorder. Individuals with a co-occurring substance use disorder may have on average higher levels of functioning than those with a serious mental illness alone.

This study had several limitations. These include the use of clinical records to assess substance use diagnosis and the relatively brief follow-up period. Clinicians may have underreported substance use. Thus the “no co-occurring” sample may have included some clients with a co-occurring substance use diagnosis. However, the rate of 34% of clients with a substance use disorder is consistent with epidemiologic studies (

1). Other limitations include the use of a single site as well as unclear severity of substance use disorder, functional status, and treatment history of clients.

Conclusions

This study confirms that clients with co-occurring substance use disorders have high rates of interest in employment, have difficulty accessing supported employment services, and have comparatively good outcomes once they access services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.