Family members play important roles in the lives of adults with serious mental illnesses (

1) and often seek information and support regarding treatments, relevant resources, coping, communication, and problem-solving skills (

2–

6). Although virtually all reviews recommend including families in the care of persons with mental illness (

7), reported rates of provider contact with family members rarely exceed 50% (

8–

10). Families often report dissatisfaction regarding their interactions with the mental health system (

4,

11–

16).

The self-help movement has offered a partial remedy to unmet family needs by offering programs delivered by and for family members of individuals with mental illness. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) sponsors the most widely disseminated such program, the NAMI Family-to-Family Education Program (FTF). FTF is a 12-week course with ahighly structured standardized curriculum, developed and conducted by trained family members.In weekly two- to three-hour sessions, family member attendees receive information about mental illnesses, medication, and rehabilitation. They also learn self-care, mutual assistance, and communication skills, as well as problem-solving strategies, advocacy skills, and ways to develop emotional insight into their responses to mental illness (

17).

Whereas research examining the effectiveness of family education administered by clinicians has been extensive, research on family self-help programs has been limited (

7). Pickett-Schenk and colleagues (

18–

20) compared families receiving the Journey of Hope, an eight-week family-led education course, with a wait-list control group. Families involved in the course reported better fulfillment of information needs, lower levels of depression, improved family relationships, and improved satisfaction in their caregiver role. However, Journey of Hope was restricted to Louisiana and is not currently available. Two previous studies suggested that FTF reduces participants' subjective burden and increases their perceived empowerment. The first was an uncontrolled trial; in the second, participants served as their own controls during a waiting list period (

21,

22). In this study we tested the effectiveness of FTF with a randomized controlled design. We hypothesized that FTF outcomes would include increased empowerment, greater knowledge, and reduced subjective burden, as well as improved emotion-focused coping and family functioning with reduced distress.

Methods

Settings and design

Individuals were randomly assigned to take the FTF class immediately or to wait at least three months until the next FTF class (control condition). Those in the control group could use any other supports offered by NAMI, by mental health professionals, or in the community. The study was conducted in the areas of Maryland served by five NAMI affiliates: Baltimore Metropolitan region and Howard, Frederick, Montgomery, and Prince George's Counties. FTF classes were delivered by trained volunteer family members, according to usual NAMI locations and schedules. The study did not alter the FTF classes or their delivery; every class could include both research participants and nonparticipants. Anyone contacting the NAMI-Maryland office or a participating affiliate and expressing interest in FTF received basic information and was referred to NAMI-Maryland's FTF state coordinator. She spoke with each person to determine whether he or she was suited to participate in the FTF program. She described this study to suitable candidates, conducted a preliminary screen for eligibility, and determined the candidate's willingness to participate in the study. Research assistants contacted eligible willing family members and obtained informed consent via telephone in a protocol approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

Consenting participants were assessed at baseline (before FTF started), randomly assigned to immediate FTF or to a wait-list control group, and interviewed again three months later (after those assigned to FTF completed the course) by a research assistant unaware of assigned study condition. Assessments were conducted with a structured telephone interview that lasted approximately 60 minutes. A stratified block randomization procedure was used with stratification by site and randomly varying block sizes. After the baseline interview, an independent member of the research staff informed the research assistant of the treatment assignment, which was kept in a sealed envelope; the research assistant then informed participants of their assigned condition. Participants were told at the beginning of each follow-up interview not to reveal their study condition; if that occurred, the interview would be stopped and continued with another interviewer. Participants were recruited between March 15, 2006, and September 23, 2009, and were enrolled in 54 different classes. They were paid $15 for each interview. At the conclusion of the second interview, the interviewer inquired about the number of FTF classes attended and the participant's use of other supports during the three-month interval.

Participants

Individuals were eligible for the study if they were 21–80 years of age, desired enrollment in the next FTF class regarding a member of the family or significant other, and spoke English. Of 1,532 individuals screened, 1,168 were determined to be eligible for the study. The most common reason for ineligibility was that a person's schedule did not permit participation in FTF at the next round of class offerings. Of those who were eligible, 339 (29%) were willing to consider study participation. The most common reason for declining study participation was unwillingness to take the chance of needing to wait before taking FTF. A total of 37 additional people who were family members of potential participants were also eligible and expressed interest in the study. From this group, 322 individuals consented to the study, but four were administratively withdrawn, leaving a total of 318 consenting individuals who completed the baseline interview and were randomly assigned—160 to FTF and 158 to the wait-list control group. [A figure illustrating the eligibility and assignment process is available as an online supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Assessments and variables

We obtained background information using the Family Experiences Interview Schedule (FEIS) (

23). This instrument elicits information regarding demographic characteristics and level of involvement with the participant's ill relative, the ill relative's demographic characteristics and mental health history, the extent of contact between the participant and the ill relative, and the extent to which family members provide assistance in daily living and supervision to their ill relative.

Indicators of problem-focused coping were evaluated with empowerment and knowledge scales. The Family Empowerment Scale has three subscales: family (12 items), community (ten items), and service system empowerment (12 items) (

24). We assessed knowledge about mental illness using a 20-item true-false test of factual information (available from authors) covering material drawn from the FTF curriculum that tapped general knowledge about mental illnesses.

Emotion-focused coping was measured with four COPE subscales: emotional social support, positive reinterpretation and growth, acceptance, and denial (

25). The COPE has demonstrated good reliability and validity and has been adapted for family members of individuals with serious mental illness (

26).

Subjective illness burden was evaluated with the FEIS worry and displeasure scales (

23). The eight-item worry subscale asks respondents to rate their level of concern on different aspects of their ill relative's life. The eight-item displeasure subscale measures the participant's emotional distress concerning the ill relative's situation (

23).

We assessed distress with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The BSI-18 is a measure of psychological distress designed for use primarily in nonclinical, community populations. It measures level of somatization, anxiety, and depression and generates a total score of the respondent's overall level of psychological distress. The raw scores for the BSI-18 symptom dimensions were converted to area T scores on the basis of norm tables for community males and community females. The BSI-18 has well-established reliability and validity (

27). The modified version of the CES-D is a reliable and valid 14-item scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in the general population (

28,

29).

We assessed family functioning with the Family Assessment Device (FAD) and the Family Problem-Solving Communication (FPSC) scale. The FAD evaluates family functioning and family relations (

30) and is widely used in studies of family response to medical and physical illness, with well-established reliability and validity (

31). We used its general functioning (12 items) and problem-solving (five items) subscales. The ten-item FPSC scale measures positive and negative aspects of communication (

32).

We adapted a series of structured questions regarding the use of diverse community and clinical family support services, support groups, and attendance at FTF classes from our previous studies (

21,

22).

Fidelity

To ensure that participants received the standardized FTF program, experienced FTF teachers acted as observers to rate one session of each course. They were oriented to the purpose and procedures of the fidelity observations and were paid $40 for each completed observation. We randomly sampled one of the first eight class meetings from each 12-session course. Classes 1 and 3 were excluded because of the sensitive nature of their content. Fidelity ratings were based on a structured rating form created for a prior FTF study (available from authors) in consultation with Joyce Burland, Ph.D. (FTF creator), to capture 18 essential elements of FTF. Overall scores were calculated by deriving the percentage of indicators present. If a class meeting scored less than 75% fidelity, we randomly sampled and assessed another class meeting in that same course from among classes 9, 10, or 11 (class 12 was excluded because of its celebratory theme). Ten observers provided 49 observations. The mean±SD fidelity rating was 90%±8%. Only one class fell below 75% fidelity, and its second assessment met fidelity standards.

Data analysis plan

We first assessed the impact of loss to follow-up by using t tests and chi square tests to assess whether participants who completed the three-month assessment differed from those who did not on demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, education, income, and relationship to consumer) and baseline scores of outcome variables (coping, subjective burden, psychological distress, and family functioning).

We used multilevel regression models (SAS, version 9.2, PROC MIXED procedure) to test our main hypotheses of whether participation in FTF led to increased constructive coping activities, reduced subjective illness burden, reduced distress, and improved family functioning. The models tested for significant changes over time (baseline and three months) between conditions (FTF or control) by using the score at the three-month assessment as the dependent variable and condition as the primary independent variable, with baseline assessment score and class as covariates.

Class was included in the model as a random variable because participants taking the same class may be more similar in their response to the intervention than people from different classes. Because people in the same class (FTF condition) were likely to be more similar to each other than to the participants in the control group, we estimated this effect separately for each condition.

Another way that participants could be similar is if they were related. Direct relatives who were in the study were always randomly assigned together to the same condition. Because the family pairings were nested within classes, the variance component due to class incorporated the variance due to family. Because of the small class cluster size (4.32±2.94), we did not attempt to fit a separate variance component due to family. To control for type I error for our primary hypotheses (problem-focused coping reflected by empowerment and knowledge and subjective burden) we used the sequential Bonferroni-type procedure for dependent hypothesis tests of Benjamini and Yekutieli (

33) to control the false discovery rate at 5%. The false discovery rate is the expected (or on average) proportion of falsely rejected hypotheses. Our primary hypotheses were informed by our preliminary data. Exploratory hypotheses tested dimensions not previously examined. No error correction was used for the exploratory hypotheses of emotion-focused coping, distress, and family functioning.

Two additional sets of analyses were completed. First we repeated the identical analyses described above but included only the participants in the FTF condition who attended at least one class. Although our primary results are based on the intent-to-treat analysis including all randomly assigned participants who completed the three-month assessment, we also wanted to examine a sample of FTF participants who had some FTF exposure. This excluded 17 FTF participants who did not attend any classes.

Second, in order to address potential bias due to participant loss to follow-up, we refitted the models after using a multiple imputation procedure in a regression to impute missing three-month outcome values using the guidelines of Sterne and colleagues (

34). Predictors for the imputation model for each outcome included the following variables: class, condition, outcome variable assessed at baseline, baseline variables predictive of loss to follow-up, and other measures correlated with the outcome measure at baseline. Thirty imputed data sets were generated and analyzed for each outcome using SAS PROC MI. Results of the analysis of each of the 30 data sets were combined with the use of SAS Proc MIAnalyze. These analyses did not substantively change our findings.

Results

Participants

Compared with individuals who refused study participation, consenting individuals were younger (51.9±10.9 versus 53.5±11.6 years; t=−2.13, df=1,063, p=.034) and more likely to be women (241 of 313, 77%, versus 601 of 849, or 71%; χ2=4.53, df=1, p=.033). Consenting and refusing individuals did not differ by county or race. A total of 133 (83%) and 126 (80%) individuals in the FTF and control conditions, respectively, completed three-month follow-up interviews.

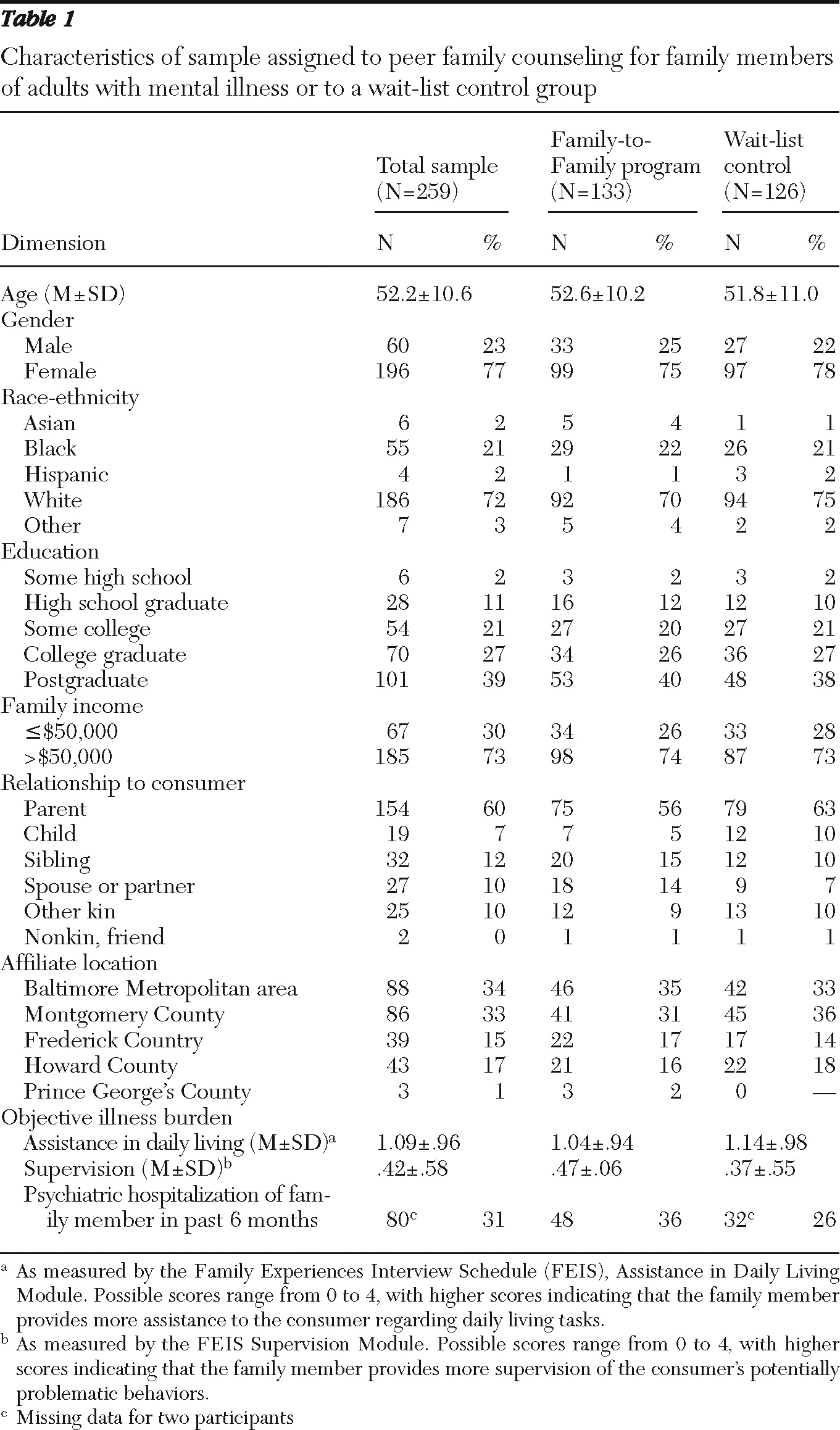

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the sample of individuals who completed both assessments. Family members who were Caucasian (p<.001) and who had income of more than $50,000 per year (p<.001), lower baseline worry (p=.012), higher baseline knowledge (p=.002), higher levels of acceptance (p=.045), and lower levels of somatization (p=.042) were somewhat more likely to be interviewed at follow-up. The characteristics of participants lost to follow-up did not differ by study condition.

Use of services and supports

Participants assigned to the FTF condition attended an average of 8.08±4.27 FTF classes. Seventeen (13%) FTF participants attended no classes, and 77 (58%) attended ten to 12 classes. In spite of instructions, five participants (4%) in the control group attended one FTF class, and five (4%) attended more than one but fewer than six FTF classes. A total of 112 participants (89%) in the control group attended no FTF classes.

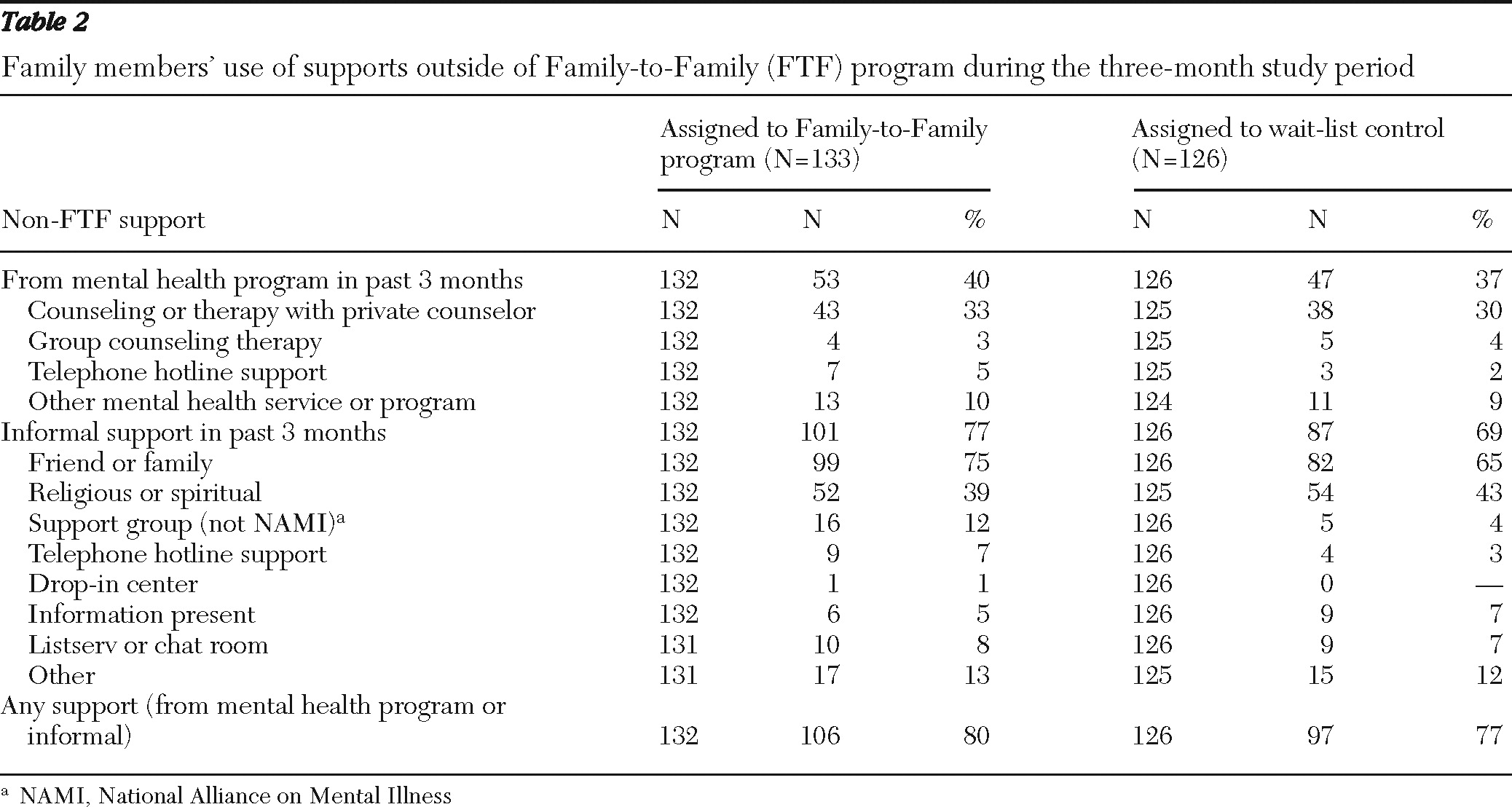

Table 2 shows the other support services received by participants during the three-month study period.

Comparison of FTF and control group outcomes

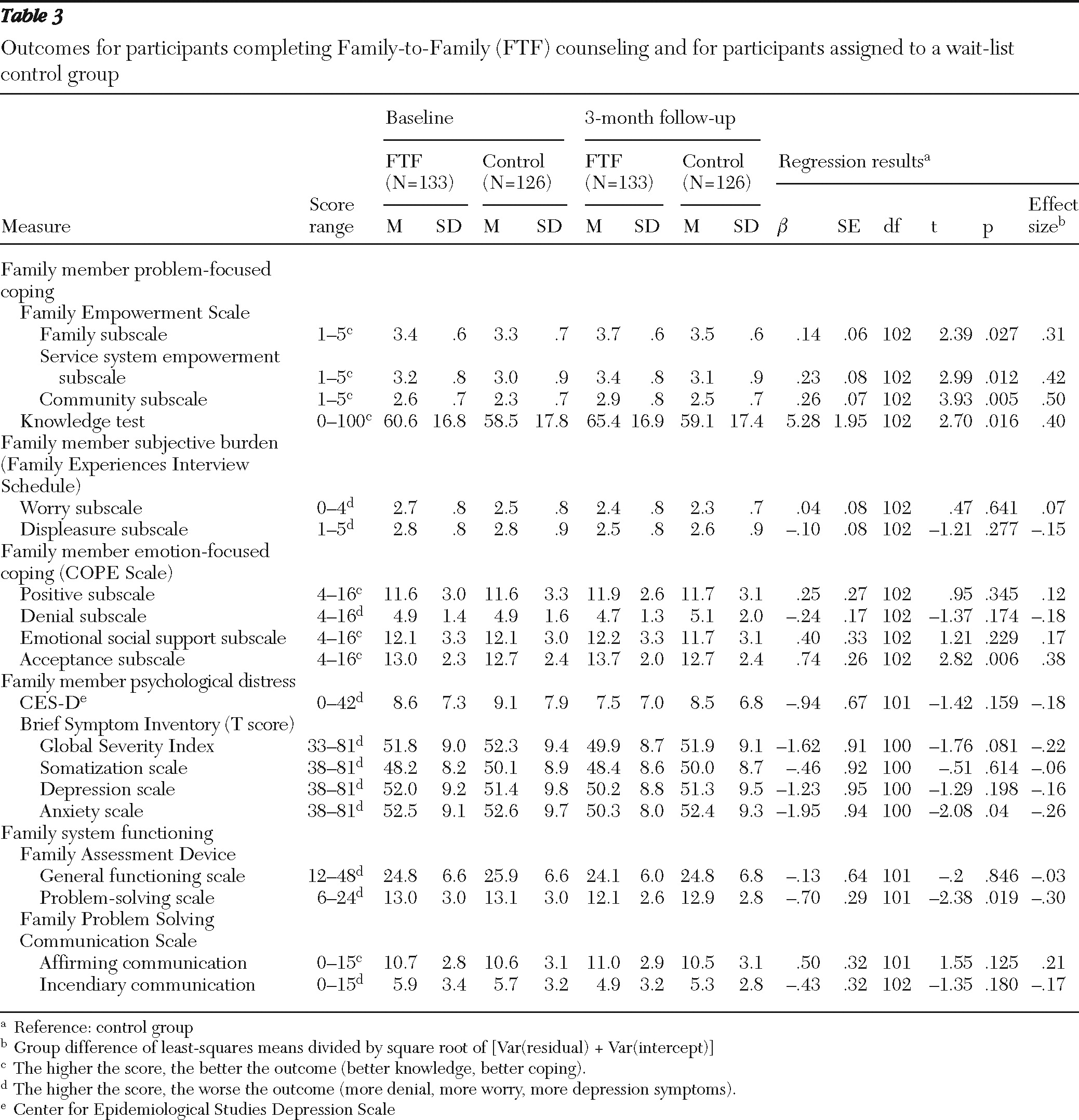

FTF participants had significantly greater improvements on indicators of problem-focused coping, as measured by empowerment (within the family, service system, and community subscales) and knowledge about mental illness (

Table 3). Subjective burden did not differ across groups. In exploratory analyses, FTF participants had significantly greater improvements on the COPE acceptance subscale, which emphasizes the importance of accepting one's family member's illness. Of the four coping subscales, the acceptance subscale is most closely related to the FTF model. FTF participants also showed significant reductions in the anxiety subscale of the BSI and significantly improved scores on the FAD problem-solving subscale compared with controls. The effect sizes for empowerment were in the medium range, whereas other effect sizes were small. Notably, changes observed on the FAD problem-solving and COPE acceptance subscales are consistent with reports in the literature in which these scales were used to differentiate clinical from nonclinical samples or changes in clinical samples over time (

25,

35–

40)

When comparing FTF participants who attended at least one FTF class (N=116) with those in the control group, we found that the differences between groups observed in the completer analysis above persisted. In addition, this narrower sample showed significantly reduced depression as measured by the CES-D (FTF baseline 8.7±7.4, control group baseline 9.1±7.4; FTF three-month follow-up 7.1±6.6, control group three-month follow-up 8.5±6.8; β±SE=−1.43±.65; t=−2.19, df=98, p=.031) and reduced overall distress as measured by the BSI Global Severity Index (FTF baseline 51.9±9.1, control group baseline 52.3±9.4; FTF three-month 49.6±8.4, control group three-month 51.9±9.1; β±SE=−2.01±.93; t=−2.17, df=98, p=.032).

Discussion

This study provides empirical support that NAMI's FTF program helps family members of individuals with mental illness in several ways. Consistent with our previous studies, FTF increased the participant's empowerment within the family, service system, and community. Knowledge about mental illness increased extending our previous finding that evaluated only self-reported knowledge.

Exploratory analyses suggest additional benefits of FTF that have not been previously evaluated. Emotion-focused coping improved with respect to acceptance of mental illness, the dimension of emotion-focused coping most relevant to FTF's curriculum. Improvements in the problem-solving subscale of the FAD suggest that FTF may influence how family members solve internal problems and navigate emotional difficulties. Although the exploratory nature of this aim requires replication, such a finding is noteworthy given FTF's brevity and its reliance on the participation of a family member without the individual who has a mental illness.

Our study also found that FTF reduced the anxiety scores of participants. This finding is consistent with Pickett-Schenk and colleagues' (

19) study of the Journey of Hope, in which that family-led course improved the well-being of family members. It is also noteworthy that the secondary analyses including only individuals who attended at least one FTF session found that FTF produced significantly reduced depression and overall distress. This is important because it models the real-life use of FTF, in that one must attend the program sessions (not just be randomly assigned to do so) to glean such benefits.

The quantitative findings of this study remarkably echo findings of our qualitative work on FTF, which suggested that the growth in empowerment and coping as well as reductions in distress together produced meaningful benefits in the lives of FTF participants (

41). Lucksted and colleagues (

41) used rigorous qualitative methods to understand how FTF achieved its impact and found that individuals who completed FTF experienced marked immediate positive global benefits with the promise of longer-term growth. They also found that these benefits could be understood in terms of self-help theory, stress-coping, and trauma-recovery models. Dr. Burland's original vision for FTF as a self-help program extended beyond empowerment, knowledge, and coping and problem-solving skills; she conceived of FTF as a way to change the “consciousness” of family members.

We were surprised that FTF did not reduce subjective illness burden as in our preliminary studies. One possibility is that this study's sample was different, because the two preliminary studies (

21,

22) did not require randomization and had much higher consent rates. Although randomized trials enhance internal validity, this design has limitations in external validity; the study sample may not be as representative of all FTF participants as our preliminary work. We are addressing this possibility in a substudy focusing on individuals who declined random assignment, which will be reported separately.

In addition to the limitations imposed by a modest consent rate, our study was conducted in one geographic region and relied on participant self-report. Balancing out these limitations were multiple study strengths. Our academic team's partnership with NAMI permitted us to work with five NAMI affiliates, including a culturally diverse group of participants. We were able to approach every eligible individual taking the classes during the time frame and to conduct a rigorous randomized trial without disrupting NAMI's natural delivery of FTF. Blinded raters conducted our assessments with excellent follow-up rates.

These results indicate concrete practical benefits to participants of structured self-help programs. There are combined benefits of a support group and a didactic curriculum. As one example of this new type of mutual assistance intervention, this study highlights the value of such community-based, free programs as a complement to services within the professional mental health system. Peers with lived experience may have a unique voice in teaching such programs.

To date, FTF is offered in 49 states plus Puerto Rico, two Canadian provinces, and three regions in Mexico and Italy. It has over 3,500 volunteer teachers and 250 trainers of new teachers. In each locale it is supported by a combination of grass-roots donations or municipal mental health funds. The program is free to participants. Since 1991, an estimated 250,000 family members have participated in FTF classes in the United States (personal communication, Burland J, Aug 2010). In each locale, some attendees are later trained to teach the program, and a few of them receive still more training to become trainers of future teachers, which allows the model to sustain itself.