One of the key features of schizophrenia is its debilitating impact on psychosocial functioning (

1). Individuals often experience difficulties in work, social interactions, and activities of daily living, as well as poor treatment adherence and recurrent relapses (

2,

3). Although empirically supported interventions have been developed to manage these difficulties, few clients have access to them (

4). Policy makers in the United States, as well as in Sweden, have acknowledged the need for action, and the past decade has witnessed growing efforts to increase the availability of evidence-based psychosocial interventions for individuals with schizophrenia (

5).

The illness management and recovery (IMR) program includes several components that have empirical support in the treatment of schizophrenia—psychoeducation, social skills training, relapse prevention, behavioral tailoring for treatment adherence, and coping skills training for managing stress and symptoms—all framed within the concept of recovery (

6,

7). The program is curriculum based and delivered in an individual or group format over 40 or more sessions. Both open and controlled studies have demonstrated its effectiveness for people with severe mental illness (a major psychiatric disorder associated with persistent impaired functioning in areas such as work, social relationships, and self-care) and in various settings, with good fidelity to the model (

8–

10). This article describes the first controlled study of the IMR program delivered exclusively to persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The aim of the study was to implement and evaluate the effects of the IMR program in an outpatient setting for individuals with schizophrenia.

Methods

The study was a randomized controlled trial that compared the IMR program to treatment as usual. The study was conducted at six psychiatric outpatient rehabilitation centers in the county of Uppsala, Sweden. Participants were recruited between May 2006 and May 2007. The study was approved by the regional ethical review board.

Participants

Participants were recruited from rehabilitation centers serving individuals with psychotic disorders. Inclusion criteria were a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, proficiency in Swedish, and willingness to provide informed consent after receipt of detailed study information. A computerized random-number generator was used to assign the 41 participants who completed the baseline assessment and gave informed consent to one of the six IMR program groups (N=21) or to treatment as usual (N=20).

Treatments

All participants received extensive outpatient psychiatric services at the rehabilitation centers, including case management, psychiatric treatments (antipsychotic medication and psychotherapy), and access to recreational and therapeutic activities, such as social, leisure, work, and support activities. Participants in the IMR group received IMR in addition to these services.

Measures

Illness management, psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, coping, recovery, and insight were assessed at baseline, posttreatment (nine months), and follow-up (21 months). Hospitalization and suicidality were assessed at baseline and at follow-up. Participants were not reimbursed for completing assessments. Participants' case managers, who were not blind to treatment assignment, provided ratings on the clinician version of the IMR scale, and assessments of psychiatric symptoms were conducted by trained clinicians who were blind to treatment assignment (see below).

At posttreatment (nine months after baseline) all participants completed the assessments. One participant in the IMR group left the program but completed assessments at posttreatment and at follow-up and was included in the final analysis. Thirty-eight participants completed the follow-up assessments at 21 months (19 from the IMR program and 19 from the control group). Two participants (one from each group) did not respond to a request to schedule the follow-up assessment, and one participant in the IMR group had died.

Instruments

Illness management was measured with the 15-item Illness Management and Recovery Scale (IMRS). Parallel client and clinician versions have been developed to capture the target domains of the program, including personal goals, knowledge of mental illness, adherence to medication, social support, relapse prevention, coping with symptoms and functioning, and substance abuse and dependence (

11). Previous studies of the IMRS have shown good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (

12,

13). For the study reported here, the scales were translated into Swedish and then independently back-translated into English and compared with the original version to identify and correct any discrepancies.

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with a modified version of the Psychosis Evaluation Tool for Common Use by Caregivers (PECC). The PECC is a 26-item scale that is used by a trained interviewer to rate severity of psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis, negative symptoms, mania, depression, cognitive symptoms, insight, and suicidality. Interrater reliability and interscale validity for the PECC have been established (

14). Five interviewers completed two days of PECC training before the assessments, including ratings of videotaped interviews. They were considered to be fully trained when satisfactory agreement on each item was established (interrater reliability r >.80). Statistical analyses were conducted on the total PECC score and on subscale scores for psychosis, negative symptoms, mania, depression, and cognitive symptoms. The PECC insight subscale assesses insight on two dimensions: ability to identify experienced phenomena as symptoms of mental illness (for example, hallucinations, delusions, and blunted affect) and ability to see a causal relationship between experienced symptoms and the illness. A modified version of the PECC suicidality subscale was used to assess suicidal ideation. A dichotomized variable (presence or absence) evaluated suicidal ideation during the week before the assessment.

Psychosocial functioning was assessed with the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) (

15) and the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) (

16). The MANSA is a 12-item scale that elicits information about satisfaction with life as a whole and with job, financial situation, number and quality of friends, leisure, living situation, personal safety, persons in the client's household, sex life, relationship with family, physical health, and mental health. Satisfaction on each item is rated on a 7-point scale. Research has shown good validity, reasonable reliability, and associations with psychopathology (

15). Scores are reported as the mean across items. The WCQ is a 66-item scale that assesses eight aspects of the respondent's coping style—confrontive coping, distancing, self-control, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, “planful” problem solving, and positive reappraisal. The eight factors have been shown to have good internal reliability and convergent validity for persons with schizophrenia (

17). Scores are reported as the mean for each of the eight coping factors.

The Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) is a 41-item instrument assessing perception of recovery from mental illness (

18). The scale includes five factors: personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, goal and success orientation, positive reliance on others, and not being dominated by symptoms. Research indicates high internal reliability, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (

19). Scores are reported as the mean across all 41 items.

Medical records were reviewed to record hospitalizations during the year before the baseline assessment and between the posttreatment and follow-up assessments. Hospitalization was defined as admission to a psychiatric unit for at least 24 hours (dichotomized as hospitalization or no hospitalization).

Treatment with antipsychotics was monitored through the use of Defined Daily Dose (DDD), a technical unit of measurement developed by the World Health Organization for presentation and comparison of drug consumption in drug utilization research; DDD is used to investigate whether a change in outcome measures is the result of changes in antipsychotic dosage (

20). Antipsychotic dosage for each participant was converted to DDD at baseline, posttreatment, and follow-up. Results are descriptive and reported as means across the groups.

IMR program

Participants in the IMR program group were engaged in weekly sessions for nine months, during which the 40 sessions were delivered. At each psychiatric outpatient rehabilitation center, sessions were cofacilitated by two clinicians. The clinicians were recruited on the basis of expressed interest in the program, and they received five full days of training before the study. During the program, the clinicians attended weekly supervision to resolve challenges involving the participants and the group format and to ensure high program fidelity. Groups were small, with three or four participants in each. Sessions lasted approximately one hour and were conducted at the rehabilitation centers. During each session, the IMR curriculum was reviewed by use of a PowerPoint presentation that covered the following topics: recovery strategies, practical facts about schizophrenia, the stress-vulnerability model and treatment strategies, building social support, effective use of medication, relapse reduction, coping with stress, coping with problems and persistent symptoms, and getting needs met in the mental health system. At the beginning of the program, participants identified personal recovery goals that were broken down into smaller goals and worked on over the course of the program. As described in the IMR manual, the curriculum was taught with a combination of psychoeducational, motivational, and cognitive-behavioral teaching methods. Between-session home assignments were chosen by participants and reviewed at the next session. Significant others were encouraged to support participants during the program.

Statistical analysis

Baseline between-group differences in background characteristics were evaluated with chi square tests and t tests. The IMR attendance rate was calculated as the group mean of attended sessions. Relative change in outcome variables measuring illness management, psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, coping, recovery, and insight were evaluated at posttreatment and follow-up by using a linear repeated-measures mixed model with baseline data inserted as random covariates. Post hoc analyses of relative change between groups were conducted with independent t tests, with the Bonferroni correction to control for type I errors. Effect size estimates were calculated by using Cohen's d for group mean scores from baseline to posttreatment and from baseline to follow-up. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether relative change in coping skills predicted or mediated relative change in psychiatric symptoms at posttreatment and at follow-up. Linear regression was used to investigate whether background characteristics predicted IMR attendance and whether IMR attendance predicted change in PECC total scores. Dichotomous data on hospitalization and suicidality from baseline to follow-up were analyzed with McNemar tests. SPSS release 18.0.1 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

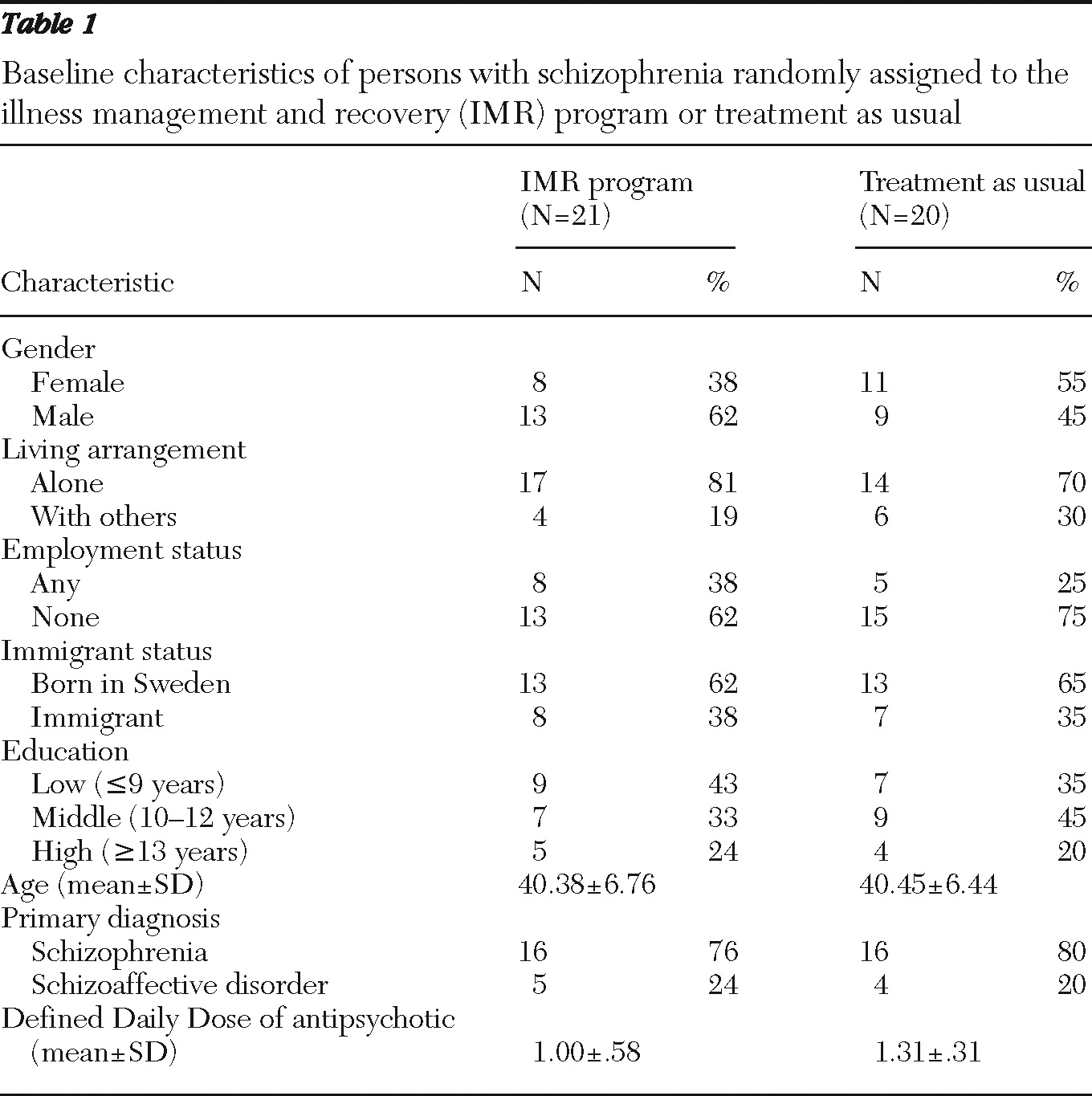

Baseline characteristics of study participants are summarized in

Table 1. No statistically significant between-group differences at baseline were noted. The mean±SD number of IMR sessions attended was 30.40±5.16 (range 21 to 40).

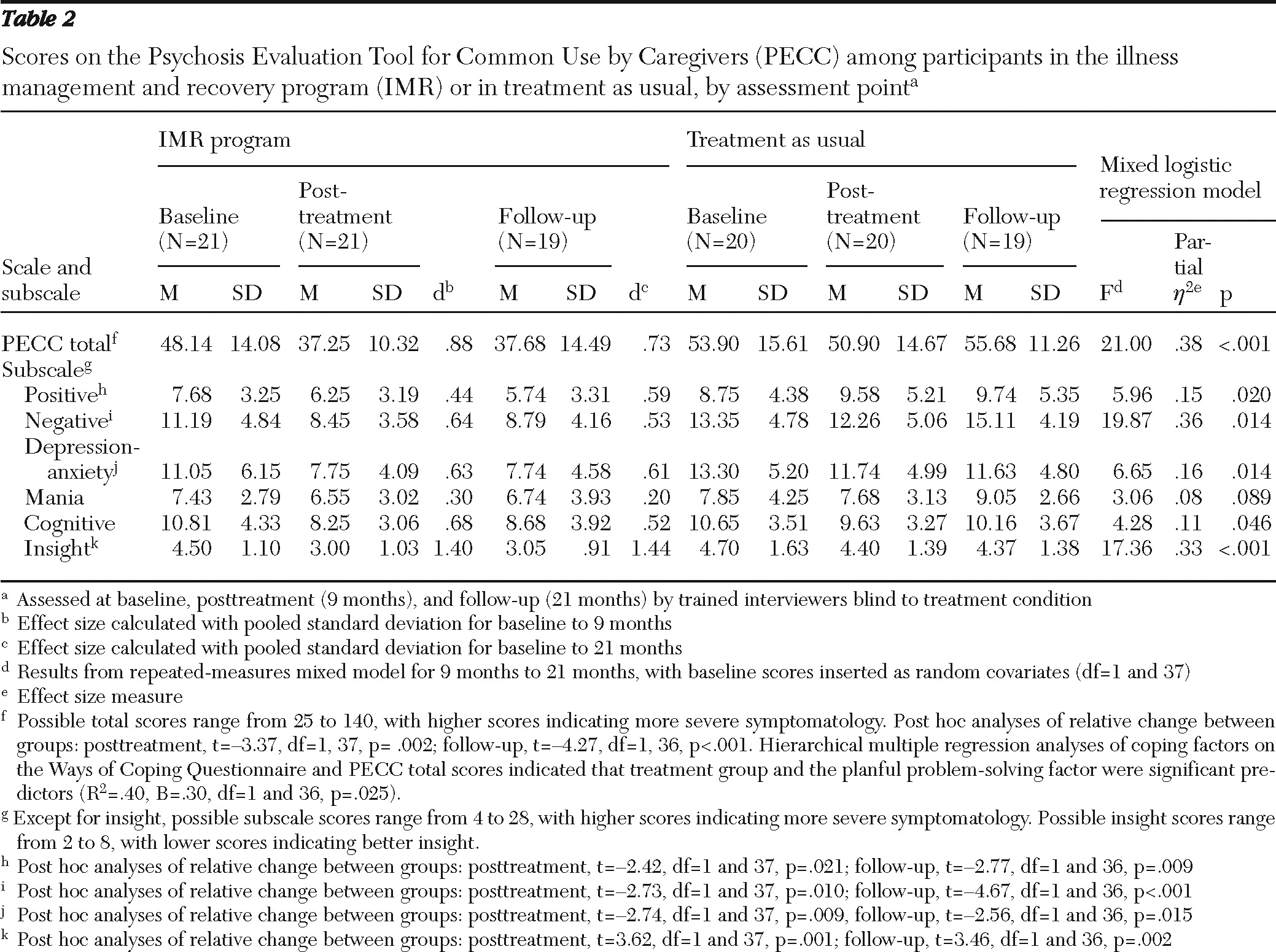

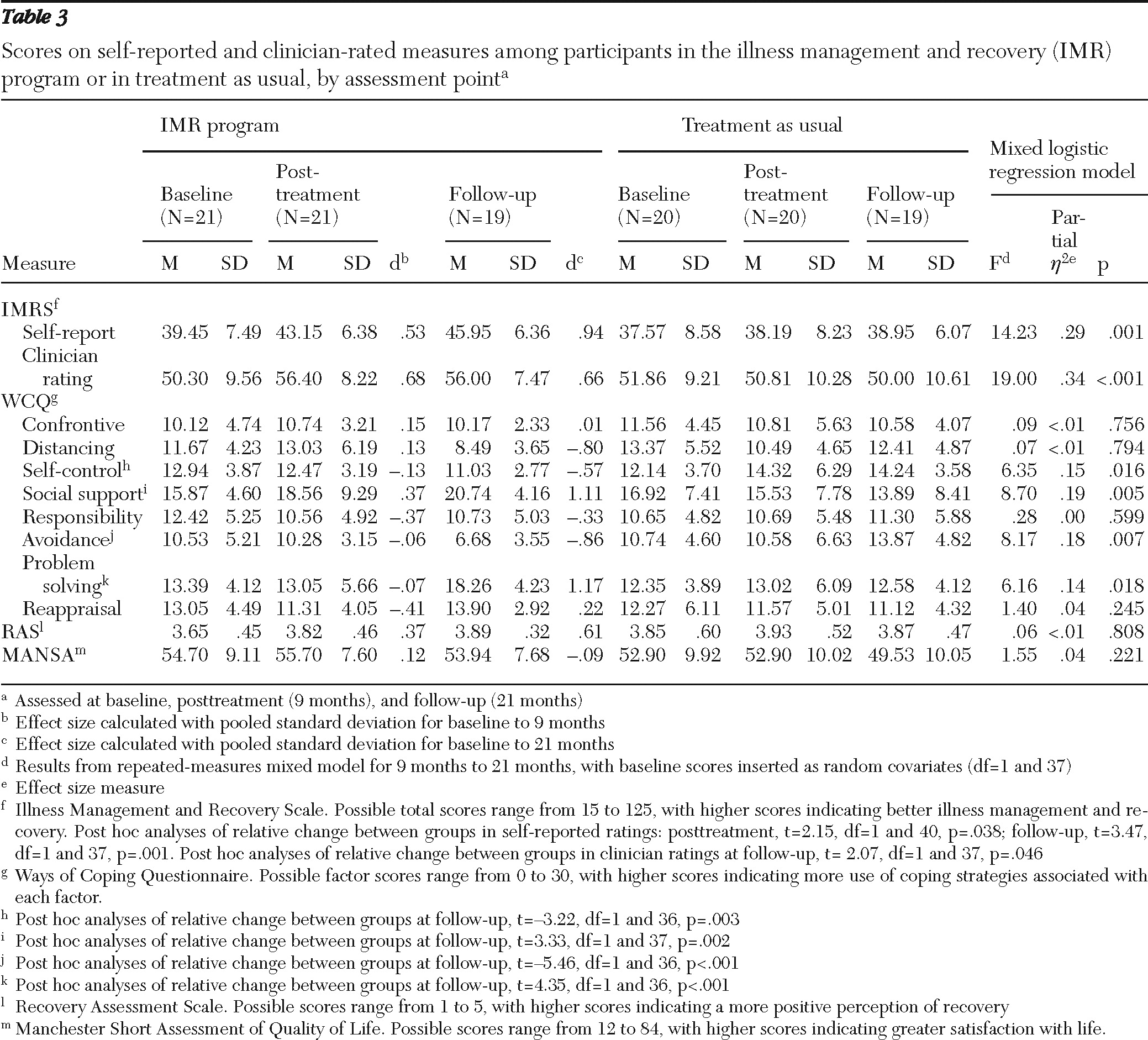

Data for the three assessments (baseline, posttreatment, and follow-up) are summarized in

Tables 2 and

3. Compared with participants in treatment as usual, those in the IMR program demonstrated greater improvement in illness management as measured on the self-reported and clinician-reported versions of the IMRS. Statistically significant differences were found between self-reported and clinician-reported IMRS ratings at both posttreatment and follow-up, when the analyses controlled for baseline ratings. In addition, IMR program participants demonstrated significantly greater reduction in total PECC scores and scores on the PECC subscales for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, depression and anxiety, cognitive symptoms, and insight. Moreover, they improved significantly more than participants in treatment as usual on three WCQ coping factors—seeking social support, escape-avoidance, and planful problem solving. Participants in treatment as usual improved on the self-control coping factor.

The relative change in the WCQ planful problem-solving factor between baseline and posttreatment predicted the decrease in total PECC scores at posttreatment (

Table 2). No other WCQ factor made a statistically significant contribution to predicting psychiatric symptoms at posttreatment or at follow-up. A statistically significant increase in DDD was noted for participants in treatment as usual at nine months. However, no statistically significant differences were observed for either of the groups between assessment points for any other WCQ factors or RAS factors, for the MANSA score, or for the PECC mania subscale.

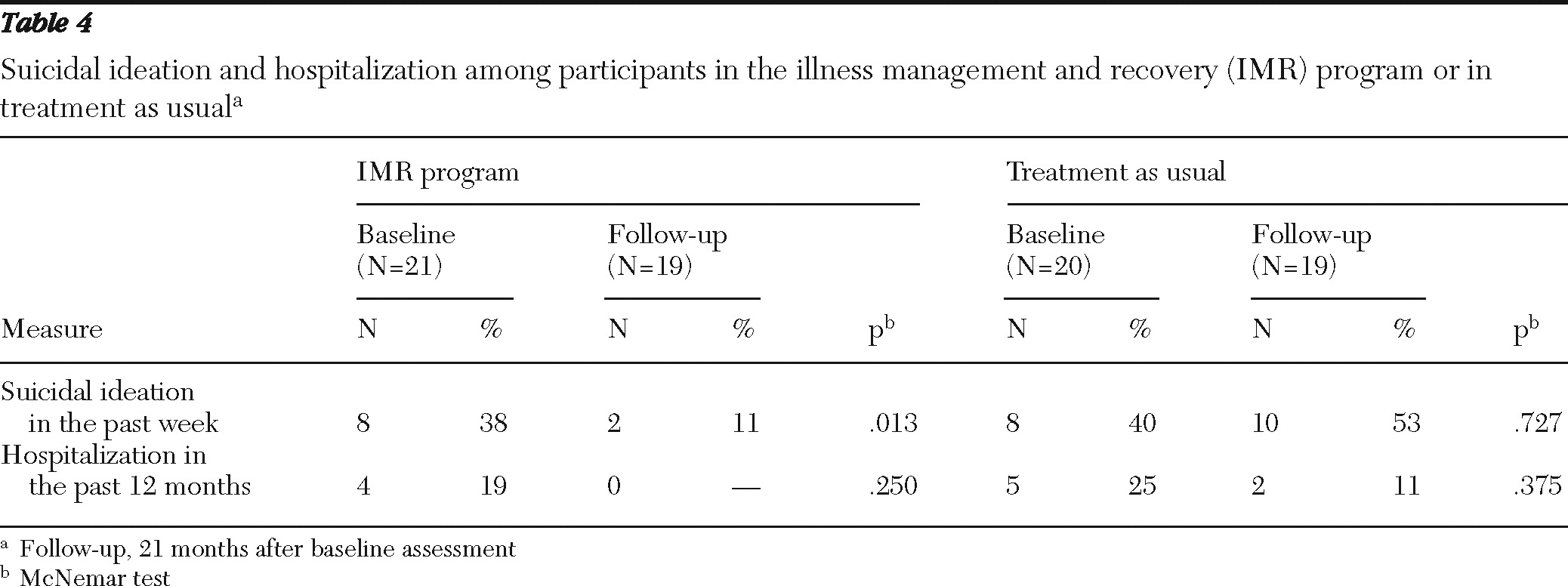

Results of the dichotomous data for suicidality and hospitalization are summarized in

Table 4. A statistically significant decrease in suicidal ideation was found for IMR program participants between baseline and follow-up. No differences in hospitalization from baseline to follow-up were found for either group.

Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial of the IMR program delivered exclusively to persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and the first IMR trial conducted in Sweden. The general pattern of the results supports previous findings of the effects of the program (

8–

10). IMR program participants showed significant improvements in illness management as indicated by self-report measures and nonblinded clinician ratings. In addition, assessments by interviewers blind to treatment assignment indicated significant improvements in overall psychiatric symptoms, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and depression-anxiety as well as improved insight over time among IMR program participants compared with participants in treatment as usual. Participants in the IMR program also had less suicidal ideation at follow-up. This is an important finding because individuals with schizophrenia have a 12-fold higher risk of dying from suicide than persons in the general population (

21). The general pattern of results suggests that individuals with schizophrenia who participate in the IMR program can improve their ability to manage psychiatric symptoms.

The results also showed statistically significant improvements favoring the IMR program in self-reported and clinician-reported IMRS ratings. Previous reports have indicated that self-reported and clinician-reported ratings may vary widely depending on the instruments used and the neuropsychological functioning of clients and that individuals with schizophrenia who have higher functioning may underestimate their own achievements and skills (

22,

23).

Consistent with the general philosophy of the IMR program, participants demonstrated improvements in coping skills in regard to seeking social support of significant others or support in the community and in regard to adopting a more proactive or problem-solving approach to difficulties associated with severe mental illness, instead of trying to escape them. The impact of a more proactive approach may also be reflected by the decreases in total psychopathology that were predicted by the WCQ planful problem solving factor; this finding is consistent with the stress-vulnerability model of schizophrenia—a more proactive approach may lead to better psychosocial functioning and fewer relapses. Previous research has demonstrated a relationship between adaptive coping and better functioning in schizophrenia, and the findings of this study suggest that the IMR program may be helpful in training problem-solving skills (

24–

28). Post hoc analyses of the coping factors showed significant between-group differences at follow-up. Also, substantial improvement over time, with medium to large effect sizes for several outcomes, was demonstrated for IMR program participants. A similar pattern of improvements that continued beyond completion of the IMR program was found for the IMRS and for the PECC positive symptoms subscale, which may suggest that participation in the program leads to improvement over time and that long-term follow-up is necessary to better understand the full impact of the IMR program.

The WCQ self-control coping factor describes efforts to regulate emotions and behaviors. It is interesting that participants in the groups demonstrated diametrically different results, with self-control decreasing among IMR program participants and increasing among those in treatment as usual. Less effort to control one's feelings and actions may be needed when one experiences improvements in adaptive coping.

Participants in the IMR group demonstrated stable DDD over time, with a subtle and nonsignificant trend toward decreased antipsychotic dosage. However, great fluctuations in DDD were noted for participants in treatment as usual. This may indicate that the IMR program can improve participants' ability to manage antipsychotic treatment. Throughout the IMR program, participants received psychoeducation about schizophrenia and available treatments and about how to use medication more effectively. This may have resulted in more effective antipsychotic treatment without significant changes in dosage.

Contrary to previous research, no statistically significant differences over time or between groups were found in quality of life or perception of recovery. Results for both the MANSA and the RAS were positively skewed with little variance, which may reflect a positive and fairly stable perception of quality of life and of recovery from mental illness in this sample. Another possible explanation is the small sample and insufficient statistical power.

The decrease in hospitalizations for the IMR group was not statistically significant. Low hospitalization rates at baseline suggest a possible floor effect that precluded evaluation of the impact of IMR on hospitalization. Future studies might focus on clients who have recently experienced a hospitalization and are therefore at increased risk for rehospitalization.

The study had some notable limitations. First and foremost, the small sample raises the threat of type II error, which was to some extent countered by increasing the power of the repeated-measures mixed model. However, statistical procedures cannot eliminate this risk. Second, multiple post hoc analyses for the outcome variables may have increased the probability of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis for some of the analyses, introducing type I errors. The Bonferroni correction was used to avoid the increased risk of type I errors, which in turn may have produced an overly conservative estimate of the results. A third limitation is that nonblinded clinician ratings on the IMRS may have introduced biases in favor of the IMR group. Because clients' self-reports indicated significant and similar improvements and because blinded ratings of psychiatric symptoms were used, this concern was partially alleviated.

Fourth, the study used a control group that received treatment as usual, and although both groups received extensive outpatient psychiatric services, improvements in the IMR group may have resulted from nonspecific effects. For a better understanding of the treatment effects, future studies should include an active control group or compare the IMR program with an established program. Fifth, no procedure other than weekly supervision was used to assess fidelity to the program. It remains unclear whether this procedure was effective in ensuring that the clinicians adhered to the program guidelines. Therefore, independent ratings would have been preferred for a more objective assessment of fidelity. Sixth, the lack of objective measures of functioning is a limitation. Finally, the recruitment of participants was based on convenience, which may hamper the generalizability of the findings.

There are some notable strengths of the study. The IMR program was evaluated in a setting that provides a broad range of psychiatric treatments and support for individuals with schizophrenia, and thus the findings may generalize well to other settings serving this population. The study design was rigorous and stringent, with randomization, blinded ratings, intention-to-treat statistical analyses, and post hoc analyses to investigate changes in the various continuous outcomes.