Introduction by the column editor: The authors of this month's column deserve congratulations for being the first to describe a best practice to disseminate a best practice. In addition, they have demonstrated that collaborations between academia and corporate philanthropy can be constructive.

The mental health field increasingly emphasizes the use of research-validated interventions, called evidence-based practices. The move toward evidence-based practices aims to reduce the enormous gap between science and routine practice. This column describes the structure, operation, evolution, and outcomes of a best practice for implementation and dissemination of a national learning collaborative on individual placement and support (IPS), the evidence-based practice of supported employment for people with severe mental illnesses (

1). IPS assists people with severe mental illnesses in obtaining competitive employment, defined as part-time and full-time jobs that are open to anyone and that pay directly to the employee the same wages that others receive for the same work (at least minimum wage).

The learning collaborative model

In the learning collaborative model, multidisciplinary teams from several health care sites meet with researchers to discuss their processes of care and desired improvements. Teams select targets for change, establish a strategy and benchmarks, visit and support each other, and monitor key outcomes (

2). In 1995 the Institute for Healthcare Improvement formalized the strategies of learning collaboratives in the Breakthrough Series (

3). The learning collaborative approach relies on transparency (sites share process and outcome data), examination of natural variation (site variation in outcomes), and peer support (participants at low-performing sites learn from those at high-performing sites).

A recent systematic review of research on the learning collaborative model found moderate positive outcomes across nine controlled studies (

4). Although few national learning collaboratives in the mental health field have been established, the National Institute of Mental Health used this approach to disseminate the community support program in the 1970s (

5).

The Johnson & Johnson-Dartmouth Program

In 2001 the Johnson & Johnson Office of Corporate Contributions partnered with the Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center to advance implementation and dissemination of IPS in the United States (

6). As an initial one-year pilot project, the Dartmouth team collaborated with state mental health and vocational rehabilitation authorities in Connecticut, South Carolina, and Vermont to implement IPS at three sites. State leaders chose a local site in their states, Dartmouth provided training and technical assistance, and the sites documented employment outcomes, which were positive. After this successful pilot, the program has gradually expanded to 12 states (Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wisconsin) and the District of Columbia, with more than 130 separate sites providing IPS as part of the program.

The Johnson & Johnson-Dartmouth Program uses a two-stage implementation strategy (9). States receive seed money from Johnson & Johnson and match the gift over four years to launch their statewide IPS implementation. The Dartmouth team meets directly with trainers, mental health authorities, and vocational rehabilitation leaders to help plan and implement IPS. The state liaisons select local sites and provide training and technical assistance.

As part of their application process, state collaborators from mental health and vocational rehabilitation agencies specify their plans to choose initial sites, provide training and technical assistance, establish funding, and expand implementation statewide in a sustainable way. State leaders develop consensus within both systems for the implementation of IPS; create a statewide supported employment leadership team to oversee implementation, monitoring, and sustaining of IPS; and hire a full-time consultant and trainer to provide regular on-site technical assistance to participating agencies.

In the first year, the state team addresses mental health and vocational rehabilitation funding mechanisms, policies, and procedures to facilitate the adoption of IPS. The team uses a competitive site selection process to identify initial sites. The trainer consults with agency leaders regarding structures to support the implementation of IPS. The trainer meets with the employment staff to demonstrate ways to build relationships with employers and shadows employment specialists to help them develop skills. The trainer also attends multidisciplinary treatment team meetings to help team members focus on employment goals.

In the subsequent years, the state team assists sites to implement the critical components of IPS by using the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale (

7). Most sites achieve good fidelity in six to 12 months (

8). As sites achieve good fidelity, the state team expands the number of sites, using established sites as role models.

The state team conducts twice-yearly supported employment fidelity reviews; the frequency is reduced to annual once sites achieve good fidelity. The state team assumes responsibility for helping agencies to achieve good fidelity and to meet benchmarks for employment outcomes through on-site training and technical assistance.

Dartmouth collates quarterly employment data from state reports and distributes summaries. Between 2002 and 2010, the number of clients served quarterly in IPS programs grew from 792 to 9,784, and the number employed increased quarterly from 299 to 3,989.

Transition to a learning collaborative

From the beginning the Johnson & Johnson-Dartmouth Program has emphasized increasing the availability of high-quality IPS in member states. Over time, several notable developments have emerged. First, all states have continued to participate after their four-year grants have ended. Second, representatives from all participating states have continued to attend an annual two-day meeting to share information, ideas, and data. For example, as the problem of justice system involvement among mental health clients has become a major employment barrier, participants have shared strategies for helping this group. Third, state liaisons and local program leaders have welcomed opportunities to participate in research.

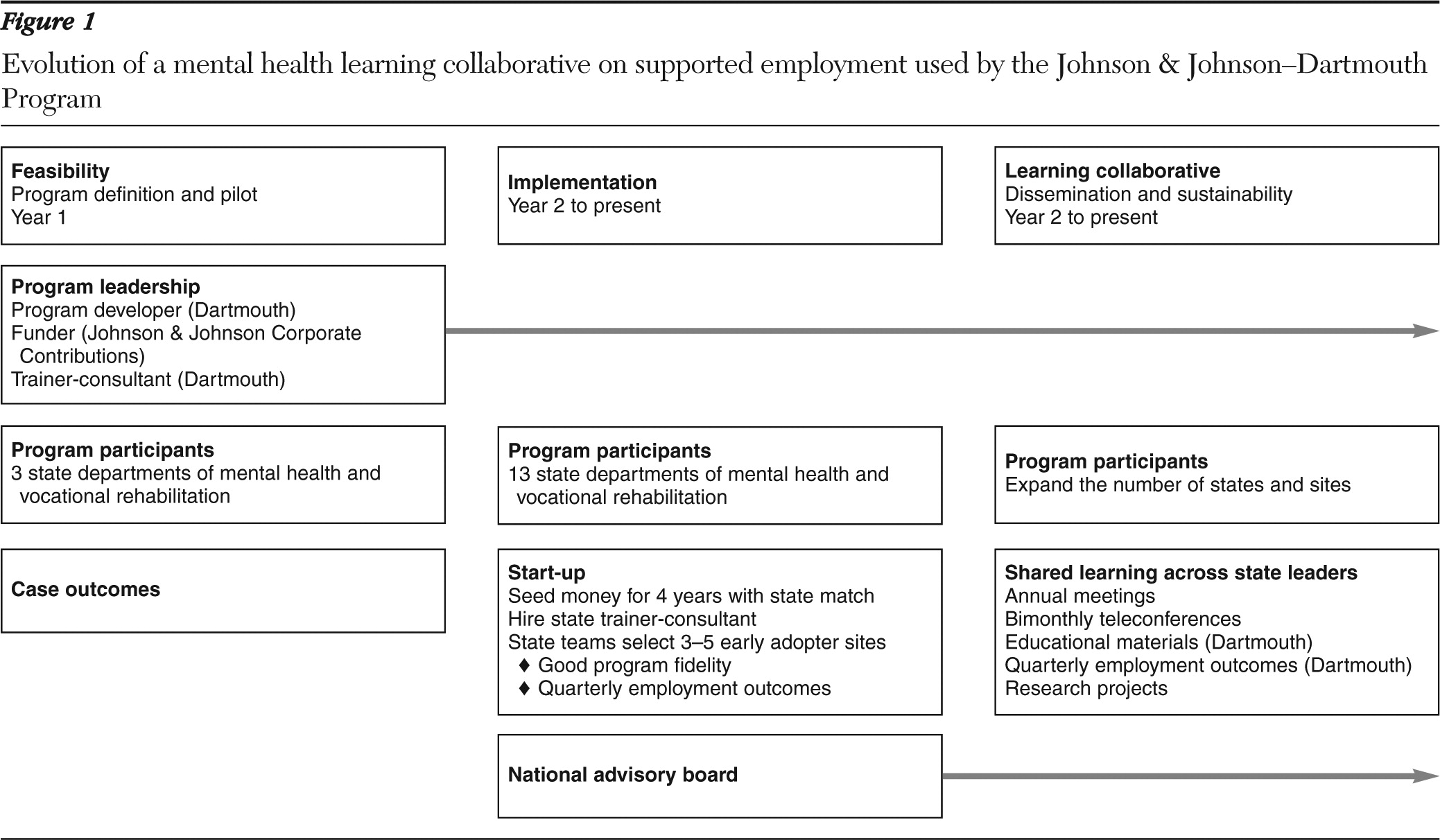

During the 2009 annual meeting, the state liaisons discussed the learning collaborative approach, recognized its relevance, and officially adopted the model. As shown in

Figure 1, many aspects of a successful learning collaborative were already in place: social connections among participants (annual meeting and site visits), commitment to learning, sharing of process and outcome data, plans for growth and for helping new members, affiliations with researchers, and discussions of innovations.

Members of the learning collaborative agreed to make decisions by consensus regarding meetings, data collection, and projects. Research proposals are discussed on the group's e-mail list and in bimonthly teleconferences. Some proposals have an impact on all the states—for example, changes in data collection—whereas participation in other projects is voluntary.

Sustaining IPS services has become a central concern of the collaborative. Under the pressures of the national recession and state budget cuts, public mental health services have continued to erode. Members of the collaborative have shared information about how to sustain services in this difficult environment.

Discussion

The essential goals of the Johnson & Johnson-Dartmouth Program's learning collaborative are to sustain IPS programs among members, to improve the quality and outcomes of IPS services, and to expand IPS programs in member states as well as in new states. To accomplish these goals, members share educational materials, clinical and administrative experiences, and process and outcome data. They also engage in peer-to-peer learning, support, and research.

The program has continued to grow despite a period of high unemployment across the United States. State leaders, providers, families, and clients recognize the centrality of employment to recovery and want evidence-based supported employment.

One unusual feature of this collaborative is its two-tiered nature. National activities generally involve the Dartmouth team and state-level liaisons, whereas leaders within each state organize training, data sharing, and other activities for local site participants. Some state leaders organize their members into a parallel learning collaborative, whereas others continue to emphasize individual contracts with specific providers.

Since adopting the learning collaborative model, the group of state liaisons examines variation in processes and outcomes at the state and the site levels. For example, the group looks at whether local or state economic, administrative, implementation, and financial differences account for employment outcomes. In addition, projects address supported education, the role of vocational rehabilitation in IPS, family advocacy, costs of IPS, and the relationship between fidelity and outcomes.

Several factors challenge the operation of this learning collaborative. Changes in leadership at the state level endanger the continuity of state support. The Dartmouth team provides new state mental health and vocational rehabilitation leaders with information about the national program, invites new state IPS trainers and mental health and vocational rehabilitation coordinators to a three-day training workshop at Dartmouth, and offers assistance. The dire state of public mental health care in the United States is another threat. As states continue to execute budget cuts, mental health care is always a likely target. The learning collaborative helps to organize and educate advocates.

Ultimately, widespread dissemination and sustainability of IPS will require changes in federal and state regulations and clear, straightforward financing mechanisms. Currently, states must combine support from several funding streams. Unclear federal policies and threats of audits and having to return payments also contribute to the difficulties that administrators face in sustaining IPS services.

Conclusions

The evolution of the Johnson & Johnson-Dartmouth Program exemplifies the best practices process. Starting with an evidence-based practice—IPS supported employment—the program disseminated the practice to 12 states and the District of Columbia, and it has developed a new best practice in the form of the national learning collaborative. By transitioning to a national learning collaborative, the Johnson & Johnson-Dartmouth Program has sustained and expanded IPS supported employment. Despite enormous pressures on community mental health programs that have generally eroded psychosocial services, members of the collaborative have been able to expand services, improve quality, and achieve good outcomes through a process of sharing goals and outcome data, regular communication, and research participation. The learning collaborative may be a best practice model for other national mental health programs.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors have received financial support from the Johnson & Johnson Office of Corporate Contributions. Dr. Martinez is an employee and shareholder of Johnson & Johnson.