Although mental disorders are highly prevalent in the South African population, many of those who suffer from these conditions do not receive adequate treatment. Results from the South African Stress and Health Study (SASH), the first nationally representative study of psychiatric morbidity in South Africa, indicate that approximately 30% of adults have experienced a

DSM-IV disorder in their lifetime, yet most are not treated (

1–

3). Low rates of treatment have been documented in many countries (

4–

10), and understanding impediments to the use of psychiatric services is of increasing global interest. The effectiveness of interventions is limited by patients who discontinue treatment prematurely. International studies suggest treatment dropout rates in the range of 17% to 22%, but to the best of our knowledge, treatment discontinuation rates in South Africa have not been published previously (

11–

14).

A number of barriers to receiving adequate mental health care, including structural and attitudinal barriers, are described in the literature. Structural barriers include financial cost of services (

15–

18) and lack of availability of services (

19,

20). Attitudinal barriers include lack of perceived need for treatment (

21–

23), the belief that the disorder will get better on its own (

24), the view that mental illness is a result of personal weakness (

25), stigma (

20,

24–

29), and the desire to deal with the problem on one's own (

11,

30). Attitudinal barriers have emerged as the more critical type of barrier in many studies in developed countries (

11,

24,

25,

30).

A number of nationally representative studies in the developed world have investigated barriers to mental health treatment (

24,

31); however, fewer data are available from developing countries, such as South Africa (

32,

33). In South Africa, barriers to treatment have not been researched as extensively as in other countries; however, low levels of mental health literacy (

34,

35), poorly developed mental health services, a limited supply of mental health professionals and staff (

36–

39), and a reliance on traditional medicine have been noted as contributing factors (

40). We used the SASH data set to examine both structural and attitudinal barriers to treatment initiation among individuals with a mental disorder, as well as demographic and clinical predictors of treatment dropout.

Methods

Sample

The SASH collected data between January 2002 and June 2004. The research protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the University of Michigan, by the Harvard Medical School Ethics Committee, and by the ethics committee of the Medical University of South Africa. The SASH had a national probability sample of 4,315 South African adults living in households or hostels (single-sex migrant laborer group quarters). All racial and ethnic groups in South Africa were represented, and the sample was selected with use of a three-stage probability sample design. The response rate was 85.5%.

Diagnostic interview

The SASH used version 3 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO CIDI) (

41). Interviewers were extensively trained and conducted the interviews in several languages. Translations of the CIDI into six native South African languages were conducted in accordance with WHO requirements. Multilingual and bilingual expert panels conducted the back-translations (

2,

3). Mental disorders assessed included anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), mood disorders (major depressive disorder and dysthymia), substance use disorders (alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence), and intermittent explosive disorder (

42,

43). After a complete description of the study was provided, written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Severity assessment

Cases that met criteria for at least one disorder were rated as severe, moderate, or mild. Cases classified as severe had at least one of the following features: substance dependence with a physiological dependence syndrome, suicide attempt in the past 12 months, severe self-reported impairment in at least two areas of functioning on the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (

44), and an overall self-reported functional impairment at a level consistent with a score of 50 or less on the Global Assessment of Functioning (

45). Cases were classified as moderate if they had moderate role impairment in at least two SDS domains or substance dependence without a physiological dependence syndrome. The remaining cases were placed in the mild category.

Sociodemographic correlates

Sociodemographic data included age, sex, education (low, low-average, average-high, and high), marital status (married, formerly married, and never married), and household income (low, low-average, average-high, and high).

Mental health service utilization

The mental health service utilization module of the questionnaire assessed participants' treatment received in the past 12 months for problems associated with “emotions or mental health.” The list of treatment providers included a psychiatrist, other mental health professional, a general practitioner or other medical doctor, any other health professional, traditional healer, religious or spiritual advisor, and any other healer. Treatment continuity was also assessed.

Predictors of treatment dropout

Respondents who reported receiving mental health treatment in the past 12 months and who discontinued treatment before the provider indicated that they should were considered to have dropped out of treatment. Possible predictors of treatment dropout included in the assessment were insurance for treatment of mental illness (yes or no), previous mental health care utilization, number of visits, and number of different treatment sectors accessed in the past 12 months. Owing to the small sample, we excluded the complementary-alternative medicine (CAM) sector from the analysis of treatment dropout predictors. However, we examined whether adjunctive CAM in the previous 12 months had influenced treatment discontinuation from other sectors.

Data analysis

The final sample of participants was weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households and for differential nonresponse relative to demographic and geographic factors and to compensate for residual discrepancies between the sample and the population. These weights were used on all data analyses, which were carried out with SAS and SAS-Callubale SUDAAN version 8.2 software. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine variations in reasons for not seeking treatment in relation to sociodemographic correlates and disorder severity.

This article covers data from two separate analyses that were restricted to different samples. The analysis of reasons for seeking treatment was restricted to persons with a 12-month mental disorder, whereas the sample for the dropout models included anyone who received treatment in the previous year, even though they were not necessarily diagnosed as having a psychiatric disorder in the previous 12 months.

Treatment received in the past 12 months was aggregated into four treatment sectors (psychiatrist, other mental health professional, general medical sector, and human services treatment). The median number of visits, interquartile range of visits, and proportion of patients who completed or discontinued treatment and who were still in treatment were examined for each sector. Multivariate logistic models were run for each of the outcomes (overall, initial contact [one or two visits], later contact [three or more visits], and treatment dropout by type of provider [psychiatrist, other mental health professional, general medical, or human services]). Predictor variables included the number of visits, age, sex, marital status, education, income, insurance, previous mental health treatment, mental disorders, number of disorders, number of providers, and CAM. Dropout by number of visits was examined by using Kaplan-Meier curves. Dropout predictors for the early (first and second) visits were compared with data for later (third or more) visits. Statistical significance on the basis of two-sided tests was set at p<.05.

Discussion

As previously reported, SASH revealed low rates of treatment among South Africans who met criteria for a past-year mental disorder: 25% had accessed mental health services, and 20% of those dropped out of treatment. The United States has the highest rates of treatment of any nation, but less than half of persons with mental illness (42%) receive care (

10). Data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication indicate that 22% of patients discontinued treatment prematurely (

14). Dropout rates are also unfavorable around the world; for example, in a developing country such as China, 30% of patients discontinue treatment prematurely (

10).

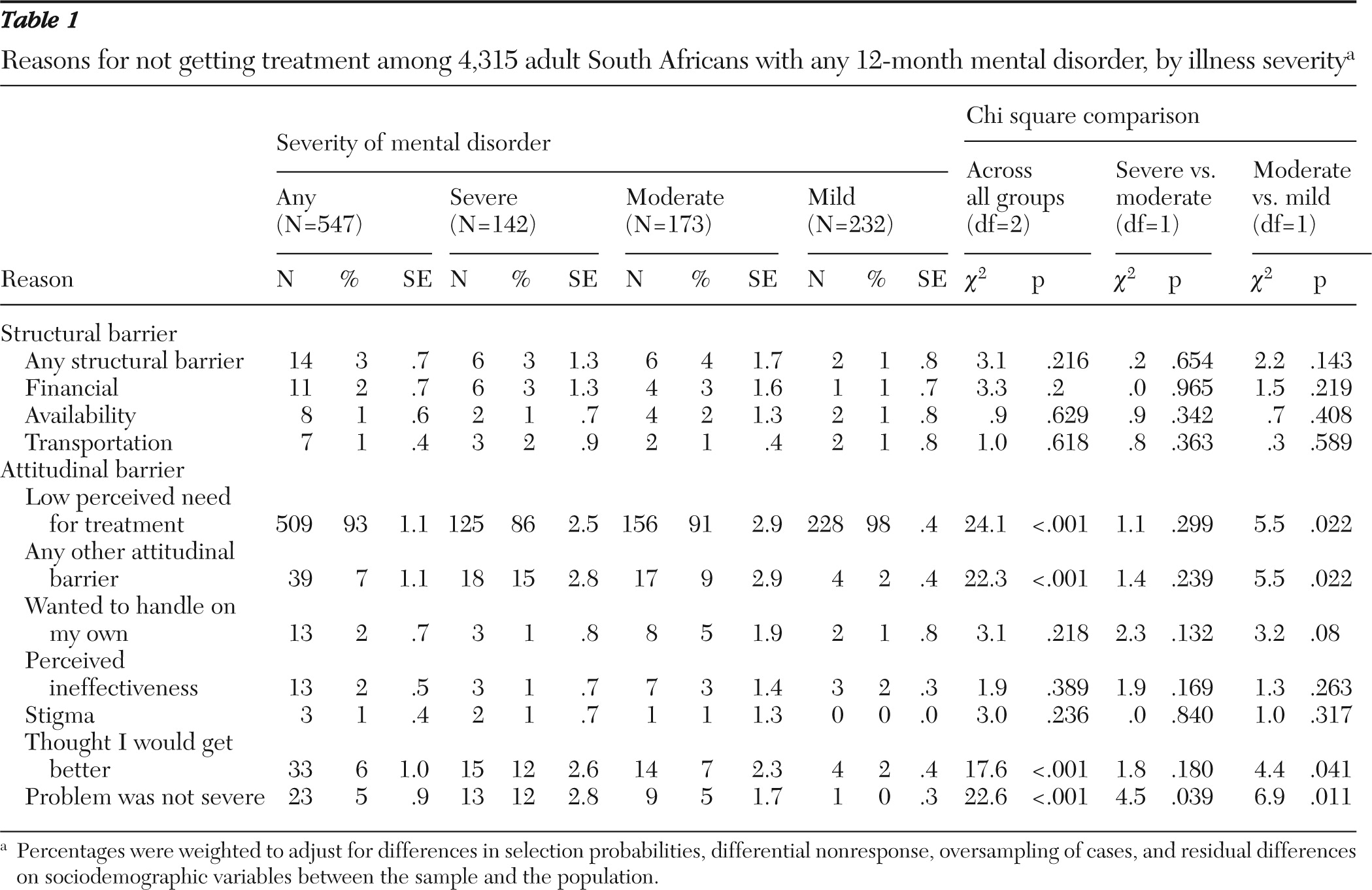

Our data indicate that most of those who did not access mental health care did not perceive that they needed treatment. Consistent with findings of previous studies in the developed world, low perceived need for treatment was by far the most prevalent impediment (

21–

23). Thus despite differences in actual proportions of those accessing mental health care, similar barriers are apparent across the developed and developing worlds.

Arguably the strongest barrier to treatment in the South African population involves the knowledge and beliefs about mental illness that aid recognition, management, or prevention. Studies investigating explanatory models of mental illness in Africa have revealed that depression, for example, is not seen as an illness but rather a result of psychological difficulties resulting from a number of external factors, such as poverty, alcoholism, or poor marital relations, which are highly prevalent in the developing world (

46). The few such studies conducted in South Africa (

34) revealed that psychosocial stress is cited more frequently than biological etiology as a cause of psychiatric disorders, and treatments for psychiatric disorders are often perceived as ineffective. Low mental health literacy may not only decrease perceived need for treatment but also lead to stigma and perceptions that treatment is ineffective (

47,

48).

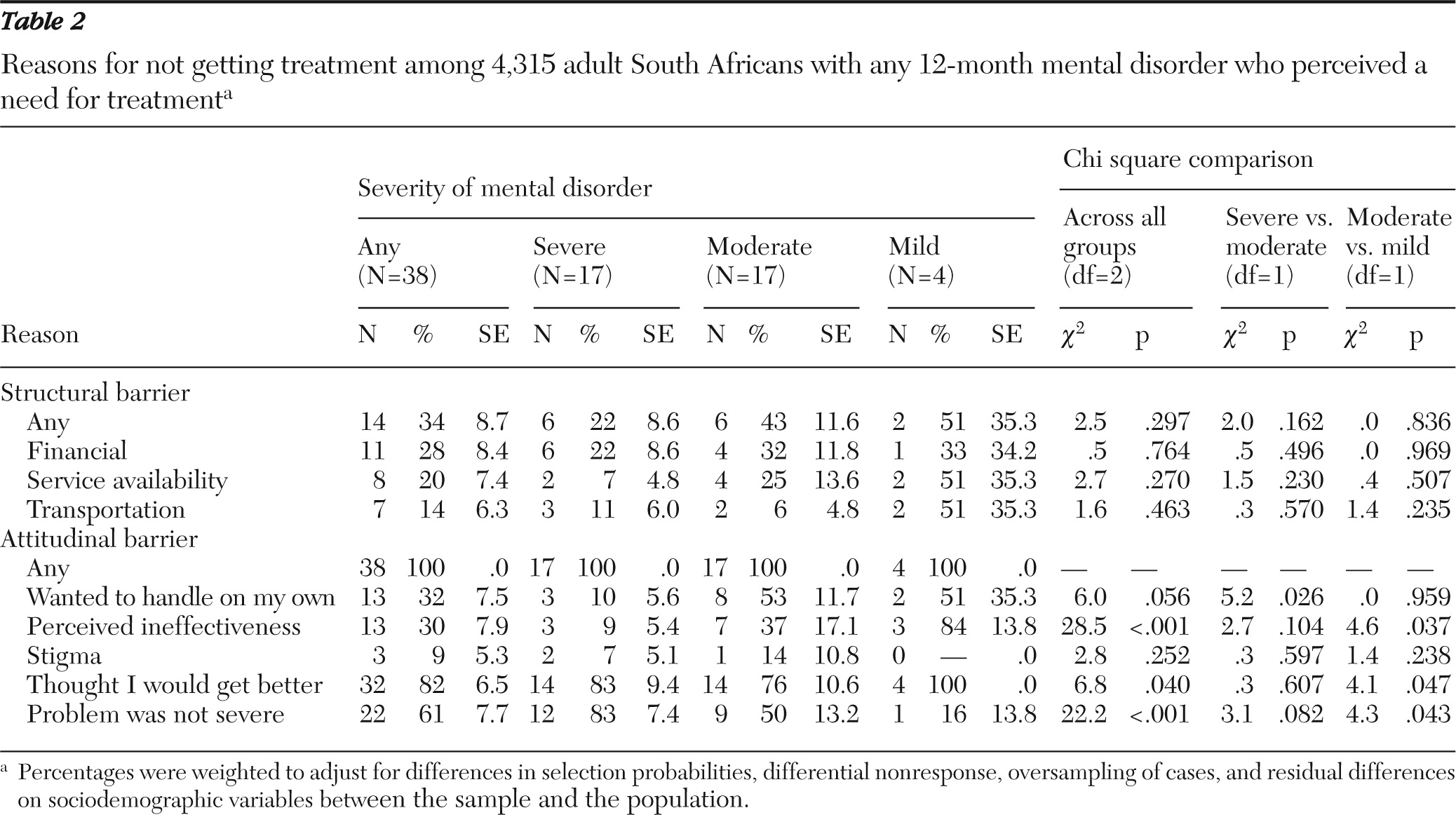

Among participants who acknowledged the need for care, attitudinal barriers greatly outweighed structural barriers. This is consistent with the findings of studies in the developed world (

11,

24,

25,

30). Consistent with data from the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands, prevalent attitudinal barriers were the desire to handle the problem on one's own (32%) and the perception that treatment was ineffective (30%). However, the perception that the problem was not severe (61%) and thinking that the problem would get better (82%) were the most prevalent attitudinal barriers that emerged from the SASH data (

24). The combination of these attitudinal barriers may contribute substantially to the well-documented delays between onset and treatment of mental disorders (

49,

50).

Although acknowledged to be a consequential problem for sufferers of mental illness (

51), stigmatization was relatively infrequently reported in this study, a finding supported by other work in the developed world (

24). One explanation for this might be that stigmatization leads patients to conceal their illness from relatives and acquaintances rather than serving as a deterrent to seeking treatment (

52).

Structural barriers, although less frequently endorsed as impeding access to services, were still notable. As might be expected, responses about structural barriers differ depending on how health care services are funded and organized. For example, in one study poorer respondents in the United States were much more likely to report structural barriers than those in the Netherlands and Canada because they were often uninsured and therefore had to bear the cost of treatment (

24). South Africa's ethnic populations have distinct socioeconomic profiles and cultural identities; health services are underfunded, fragmented, and vary greatly by geographical area (

37–

39). It is important that when attitudinal barriers are overcome, structural and system-level problems are not an additional barrier hindering appropriate access to mental health care.

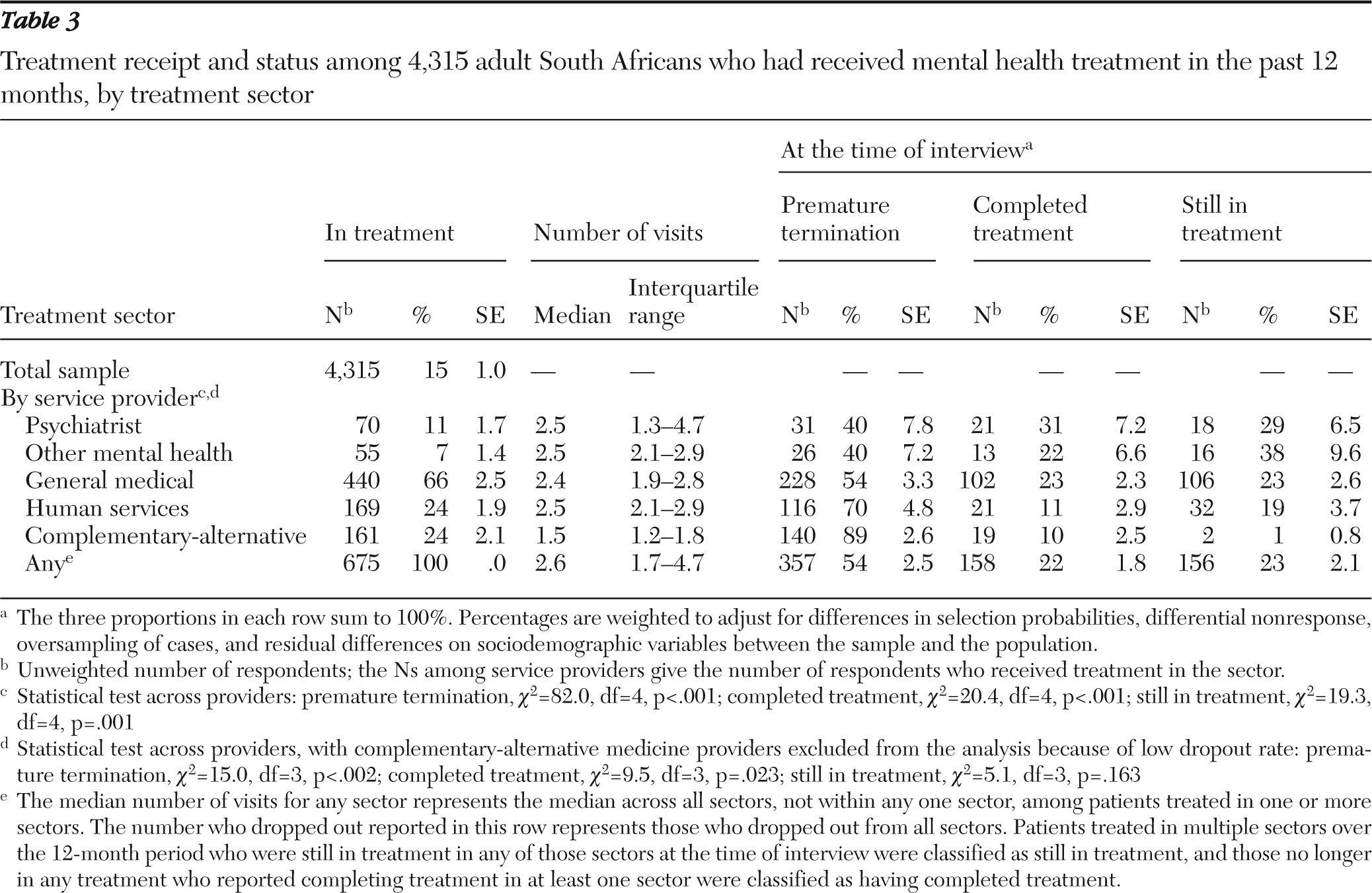

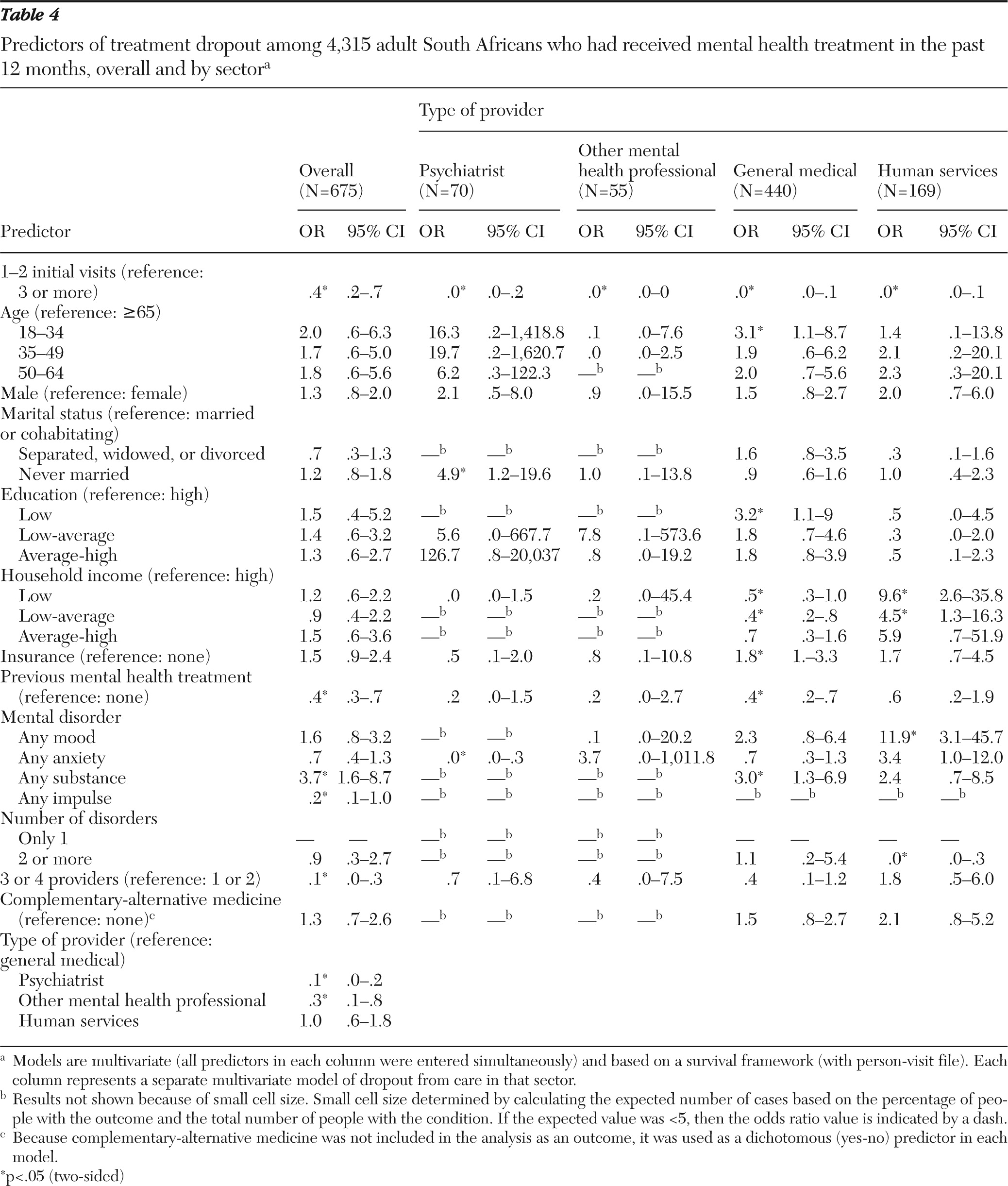

With respect to mental health treatment dropout, the overall dropout rate (20%) found in this study mirrors rates reported in the United States (19%–22%) and Canada (17%–22%) (

12–

14). Compared with mental health treatment dropout rates, dropout rates from the general medical sector were higher among U.S. respondents. In contrast, lower rates have been reported among Canadian respondents (

13,

14). We found that the highest rates of discontinuation were from the CAM and human services sectors. As in prior work (

53,

54), previous mental health treatment decreased the risk of premature treatment dropout. With regard to timing of dropout, discontinuation rates were less for other mental health professionals during the initial visits and for psychiatrists during later visits. This may point to the ability of providers in particular service sectors to establish therapeutic relationships and encourage participation in continued mental health care. However, it may also reflect the availability of effective treatment as well as reimbursement by medical insurance for certain providers. This study supports the finding that later visits represent a higher-risk period for treatment dropout (

14).

We did not find that gender and age were significantly associated with overall dropout, which is consistent with some data (

14). However, we could not replicate findings from other studies that found that younger respondents, males, and nonwhites are at increased risk of early treatment dropout (

11–

13,

53).

Factors influencing service utilization and discontinuation also included health insurance, income status, and the number of providers involved in a person's care. Consistent with the literature (

12,

14), the absence of health insurance increased the risk of treatment dropout after the first or second visits, particularly from the general medical treatment sectors, most likely because of out-of-pocket expenses of continued care. Patients with serious mental illness are often burdened by social and economic disadvantage, and the lack of health insurance frequently presents an obstacle to adequate mental health care (

17). Low income has also been found to increase dropout rates (

12).

When considering the influence of number of providers on treatment dropout, participants were less likely to drop out of treatment when three or four providers were involved in care. At later visits, there seemed to be a higher risk of treatment dropout from psychiatrists and the human services sector when three or more providers were involved in care. This may indicate the inability to afford multiple forms of care for extended periods. In contrast, other findings suggest that psychotherapy in addition to medication can reduce dropout rates (

12,

53). Adjunctive CAM has been associated with lower dropout rates (

14). In contrast, our findings indicated that adjunctive CAM increased the odds of treatment dropout from the human services sector at later visits. An explanation may be that some individuals who sought treatment from traditional healers had milder forms of mental illness that may have shown early recovery (that is, a nonspecific placebo effect). Alternatively, this finding may indicate that participants, particularly those with more severe illness, perceived treatment from CAM or human services as ineffective or unsuited to their needs.

Type of psychopathology affected treatment dropout; namely, substance use disorders and mood disorders increased the risk of treatment dropout from the general medical and human services sectors, respectively, whereas anxiety disorders reduced the risk of treatment dropout from the general medical sector, although not significantly. This finding is consistent with other studies (

13,

14) and is of concern because substance use disorders tend to require long-term treatment. Type of service provider also influenced dropout rates; respondents were less likely to drop out of treatment from a psychiatrist or other mental health professional than from the general medical sector.

Several limitations deserve mention, including the relatively short period of treatment seeking that was assessed, exclusion of CAM from the treatment dropout predictors' analysis because of the small sample, and the possibility of recall bias. Predictors of dropout were also not examined by race and ethnicity, again owing to the small number of nonblack (in particular Indian and mixed race) treatment-seeking participants (

2). Finally, the diagnoses indicated by the CIDI are based on criteria developed from Western concepts of mental illness and may not detect culture-bound syndromes found among indigenous groups in South Africa; also, they may underdiagnose conditions, such as anxiety and depression, among those with predominant somatic complaints rather than overt psychiatric symptoms. Notwithstanding these weaknesses, the findings of this study are useful because they provide the first national, population-level information on barriers to treatment and predictors of dropout among South Africans.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The SASH was funded by grant R01-MH059575 from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The study was conducted in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative. The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, U.S. Public Health Service, the Fogarty International Center, the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supported the activities of this initiative. The authors thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, field work, and data analysis.

Prof. Stein has received research grants or consultants' honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Lundbeck, Orion, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Roche, Servier, Solvay, Sumitomo, and Wyeth. Prof. Seedat has received research grants or travel sponsorship from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Lundbeck, and Servier. The other authors report no competing interests.