Early intervention services (EIS) for young people with a first episode of psychosis were introduced into the health care systems of many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, starting in the early 1990s. The motivation for this reform included significant and sustained dissatisfaction among users and their families with existing service structures (

3), recognition of a link between the duration of untreated psychosis and poorer long-term prognosis (

4), and an understanding of the importance of the outcome of the early phase of psychosis in predicting longer-term recovery (

5). More recently, EIS have been shown to decrease relapse and rehospitalization (

6), and they appear to be cost-effective (

7).

Results

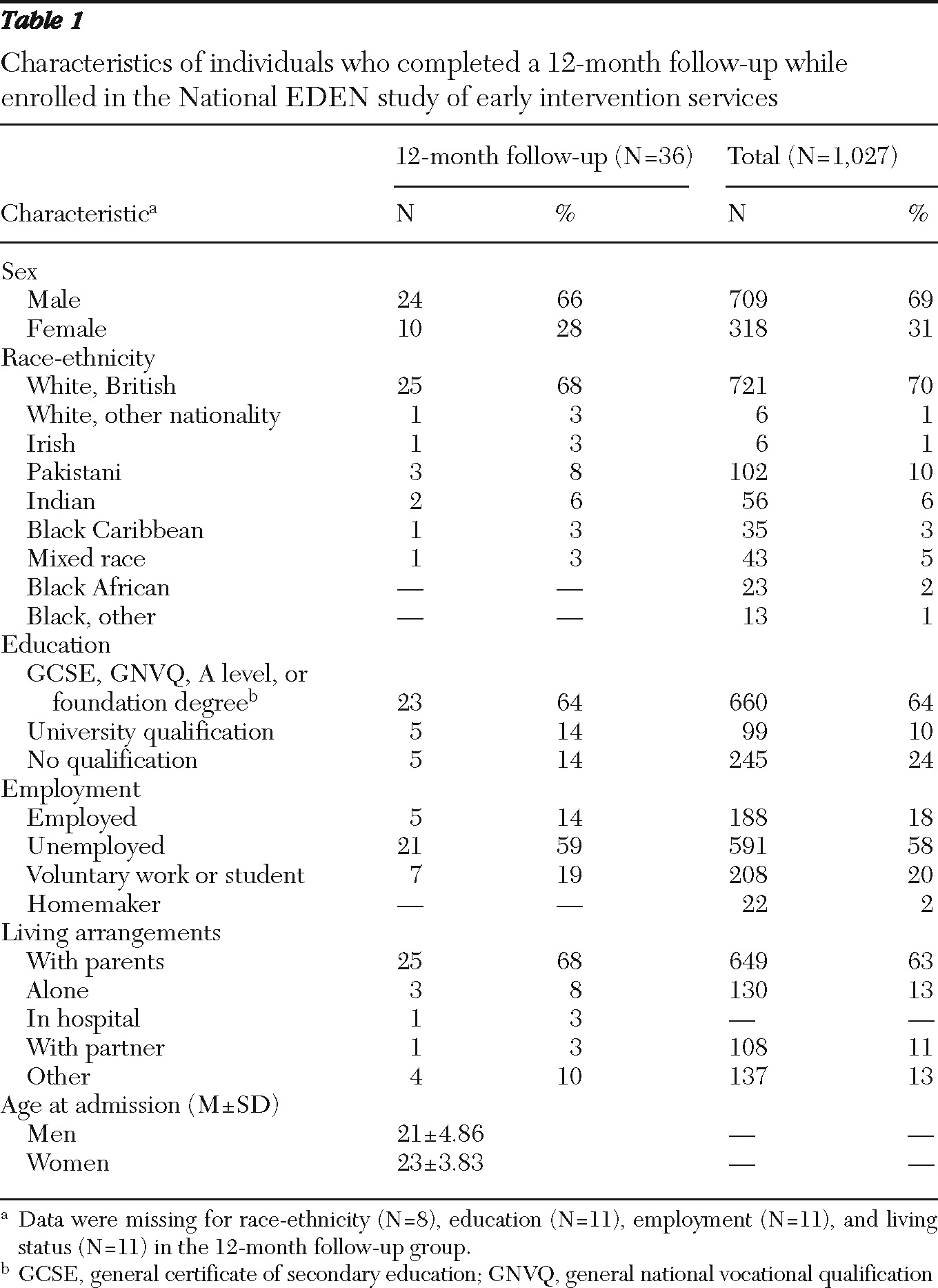

During the data collection period, 491 young people consented to take part in the National EDEN study, which included 1,027 people by study's end. Sixty-three people agreed to take part in an interview, and of those, 36 (57%) agreed to a follow-up interview. Demographic characteristics of the study population and the entire EDEN cohort are shown in

Table 1.

Three main themes of direct relevance to young peoples' experience of EIS emerged from the data: relationships with key workers, the value of family support, and changing self-identity.

Relationships with key workers

Most (N=24) of the 36 service users described EIS in positive terms, as offering activities and services that were “youth friendly” and that made sense to young people. For example, they were contacted by e-mail and texting, rather than by letter; activities were focused on sports and pop music; and education included up-to-date information technology (IT) training. Appointments with key workers were kept in local community venues or at the service users' homes rather than in secondary-care hospital settings.

Services helped users come to terms with their illness, working with them, over time, to identify triggers and early warning signs and to understand why they had become unwell. For example, one individual said of a key worker during a first interview, “I talk and he sort of chats back with me and sort of goes through it all—so he explains it all to me and my family. Now I know it's more to do with me trying to learn to cope with my anxieties.”

In particular, service users highlighted the positive nature of the relationships with their key workers and the benefits of being able to develop a long-term relationship with one individual. The positive personal characteristics of key workers, such as apparent genuineness and support, were frequently discussed. Asked to describe the relationship with a key worker in the first interview, one participant said, “I'd say very positive … it picks me up each week. Every time I see [name of key worker], it's another pick-me-up.” After 12 months, another participant said of the key worker, “I see her every two weeks. I don't know what I would do without her, to be honest with you. She's such an amazing person to have in my life at this time.”

At both time points, most people stated that they appreciated the flexible approach to the amount of care received. Service engagement was negotiated and reduced when agreed upon during their treatment. For example, at the 12-month interview one participant explained, “If I feel particularly upbeat and that, she might say, ‘Well, shall we leave it three weeks?’ but, then, if she thinks that maybe I need a bit extra, she says, ‘Okay, well, I'll come and see you in the week.’ ”

However, approximately one-third of those interviewed described an overemphasis on engagement with EIS to the point of feeling that the visits from key workers were too frequent. Yet this complaint was often associated with having had a number of different key workers because of staff turnover during the 12-month study period. As a result, participants often were expected to repeat personal stories and received the same advice. Even within six months, one participant complained, “We agreed that “C” would see me weekly, and then “D” came instead and started repeating things, and then I started seeing “E.” I had “V” come up for a bit, and she was alright, but then of course she left.”

Another participant said at the second interview, “Each change was disruptive. I was continually having to get to know different people and to tell my story, and it takes a whole load of time to build up trust in someone.”

Overengagement became a more prominent issue in the follow-up interviews, perhaps because the first interviews were based on expectations and on relatively limited contact. By the time of the second interviews, service users' comments were based on actual experience. For some service users, the continued regular presence of their key workers after 12 months reminded them that they were still, at least in the eyes of EIS, a patient in need of treatment. Yet, they had reached a point in their recovery at which they were keen to resume their lives, to be as one said, “free from everything and move on.”

In the following exchange, a user of services complains of seeing the key worker too much.

Service user: As I've got better it's not nice having somebody come in all the time, because it constantly reminds me that you're suffering from an illness. They seem to ask the same questions all the time.

Interviewer: Right, so do you feel it's too much, then?

Service user: At the moment I do.

Value of family support

Family support was described as critical by the majority of service users at both time points. Families were relied upon not only to provide practical help in terms of money and accommodation but also to serve as someone to talk to and to offer emotional security. Parents and other family members provided an informal help network, looking after an adult child at a time of crisis as they would have when the child was younger. Many parents reportedly took on tasks that they had previously relinquished, such as shopping and laundry.

Over the 12 months, most service users—even the minority of participants who had been living independently but were again living with their family—felt that family support had increased and described feeling closer to their parents. The family had usually gained a better understanding of the illness over time from frequent contact with key workers in EIS. Many families had also become increasingly involved in advocating for treatment and in helping the service users cope with symptoms, for example, by encouraging them to work with the key worker to develop and use relapse plans. They were also often actively involved in making and maintaining contact with the key workers and wider team.

At the first interview, one participant said, “Well it's helped since I've told my mum. I only told my mum about how I've been feeling a few months ago, so it's just really changed since she's known. She was really supportive and could understand that it's an illness and that you need to get some help. [I didn't tell her before because]… I felt ashamed, and I was just worried about how she would feel.”

Later, at the second interview, the participant continued to express gratitude for the mother's understanding.

Interviewer: And has your relationship with your mum changed, do you think, over the course of the last year?

Participant: Yes, definitely, yes it has. I'm more willing to say, ‘This is what I'm experiencing,’ without feeling ashamed or seeing it as a weakness. I was scared about her getting worried and things like that. But she's been great.

Changing self-identity

During the first interview, most service users talked about psychosis as an illness from which they would recover simply through time and medical help. By the second interview, however, a significant minority of service users had begun to express an emerging acceptance of a new identity, created by the illness and often associated with a sense of loss of their old self. They talked about their current situation in negative terms compared with their old selves and situations. One said, at six months, no less, “I used to be a normal person you know. … you feel so alone, and you feel jealous of normal people.”

A more negative self-identity was reinforced for some by changes in physical appearance, such as weight gain secondary to medication use and by episodes of perceived stigma involving work, friends, or wider society. Only 15 of the 36 service users were back at work or in school at the time of the second interview, which further emphasized a sense of feeling different from their old friends and their former selves. One said at the second interview, “I see quite a lot of people I used to know but because I've put on a bit of weight, and I look a bit different, they don't recognize me. I would have said, ‘Hey it's me!’ but now I'm glad they don't recognize me any more. … I wouldn't know what to say.”

EIS key workers, however, were seen as important allies in recovering a positive sense of self, through providing therapy-based coping strategies and enabling participants to meet and share experiences with other service users. One participant at six months said, “It's been all right. I'm quite proud of the activities we do. We play pool in George Street, and they're a laugh. And my key worker's helping me with computer classes.”

Discussion

This qualitative study has described in detail how users of EIS viewed their relationships over a 12-month period with key workers, with family, and with images they held of their former selves. A recent article describing qualitative studies of services for a first episode of psychosis (

18) found 27 discrete studies, but only one, in Denmark, was longitudinal in nature, and it involved only 15 individuals (

19). Longitudinal study seems particularly important when exploring an evolving illness with a cohort of young people.

The literature suggests that up to one-third of individuals with serious mental illness who have had some contact with the mental health service system disengage from care (

20). Early disengagement from mental health services can lead to devastating consequences for individuals with schizophrenia, including exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms and suicide (

21). Part of the rationale behind EIS is the need to actively engage people early in the course of the illness and to sustain engagement through a number of approaches, including offering frequent visits from key workers in low-stigma settings, using a youth-centered approach to engagement, and providing activities that are age appropriate.

Most service users in this study described their key workers as having very positive personal qualities, as being someone they could trust, and as being supportive and warm, highlighting the importance of relationality in EIS. Relationality, defined as our lived relation to other human beings, is an underresearched issue, but its role in promoting engagement in services warrants study. EIS may empower parents and other family members to help individuals maintain a therapeutic relationship (

22), in stark contrast to examples in which parents seeking help for children with first-episode psychosis encountered many problems, particularly difficulties accessing psychiatric care (

23). Positive therapeutic alliances, themselves a positive predictor of engagement, appeared to occur among EIS participants in this study (

24,

25).

The interpersonal nuances of trust and respect built up between individuals over time are perhaps even more important among service users whose illness may cause them to be considered different by wider society. Yet among a significant minority of the young people we interviewed at the 12-month follow-up, the notion of sustaining engagement for up to three years was seen as too intensive. On the other hand, those most likely to complain of overengagement were also those who perceived less continuity with key workers, suggesting that concerns about overengagement may only emphasize the importance of a positive therapeutic alliance. This study, in the context of the established and emerging literature, therefore suggests that it is important to negotiate not only the right type of EIS for young people but also the right amount of engagement in services and to review them regularly.

This study also supports findings of a previous study, that many parents of young people with psychosis appear to take on caring responsibilities they had previously relinquished as their child reached adolescence (

26). Additionally, this study suggests that service users found the family environment very supportive. Indeed, an unanticipated reward of caregiving in some circumstances was that many service users described having a more open and deeper relationship with their families than they did before their illness (

27). This finding challenges the notion lingering from Brown's work in the 1950s that parents can exert a negative influence on people with psychosis after they return home after hospitalization (

28). Brown found that people with psychosis living with their parents were more likely to be readmitted to a hospital than those living with siblings or in hostels.

The study also captured the evolving process by which service users came to terms with their illness. It suggests that from an early stage, some service users experienced a disruption in their sense of self, accompanied by a feeling of loss. For many, this new sense of self was linked to changes in physical appearance, often linked to the side effects of medication, which increased perceptions of stigma. This finding is consistent with Festinger's social comparison theory (

29), which proposed that people have the drive to evaluate and assess their abilities and opinions by comparing themselves with others they consider similar.

In a development of this theory, called temporal comparison, Albert (

30) argued that when people engage in self-evaluation, they also compare their current selves to who they had been at earlier points in time. One of the basic hypotheses of temporal-comparison theory is that such comparisons help individuals to maintain a sense of identity and continuity over time, which in turn allows them to evaluate and adjust to changes. Compared with research about social comparison theory, there is limited empirical research to document the use of temporal comparisons (

31). Comparisons with past selves, especially among young people, according to Ross and Wilson's theory of temporal self-appraisal (

32), tend to be rewarding because, in general, skills tend to improve with age and experience and people tend to regard their current selves as better. In general, images of oneself in the distant past are more likely to be derogated, whereas images of oneself from the more recent past are more likely to be enhanced.

In this study, however, service users saw themselves in a less positive light compared with their past selves, a finding that is consistent with a study by Dinos and others (

33) in which 12 individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia compared themselves negatively with their former selves. Most studies that have explored temporal comparisons, however, were conducted in the absence of threatening events or focused on acute threats that were no longer present (

34). Experiencing a first-episode psychosis is a different type of threat that has the potential to cause ongoing problems. These findings suggest that the theory of temporal self-appraisal be elaborated to include people who have and continue to experience major life changes, such as service users with a first episode of psychosis.

This study had several limitations. Most of the caregivers were family members, making the data less generalizable to use of EIS when caregivers are not family. There was also significant but expected attrition between the first and second interviews; we do not know if the individuals who agreed to the second interview were more or less likely to hold particular opinions about or perhaps have different experiences of EIS. Also, we were able to conduct follow-up interviews of service users at only one time point.

Conclusions

The study findings suggest several conclusions. First, there is a need for greater flexibility in service provision, so that service users can be engaged at the level they need for as long as they need. Engagement should not be regarded as synonymous with highly intensive contact. The ability to be flexible and reflexive to individual service users' needs in early intervention may be a better marker of the quality of services than are uniformly high levels of service engagement.

Second, family support was seen as critical by service users, and families were an important link with services. Involving and supporting families is part of the policy-implementation guidance for EIS, but this study suggests that their role in providing both practical and emotional support and in liaising with key workers may be more important than previously thought. Families may also provide a means of engagement with service users.

Third, because a diagnosis of first-episode psychosis is accompanied by major changes and continuing readjustments in many areas of an individual's life, consideration of temporal comparisons is important. EIS may need to develop even more recovery-focused strategies that take into account the relatively rapid change in service users' perceptions of their personal identity. Providing therapy and stigma-challenging activities in particular seem to be key in supporting service users as they gradually develop a new self-image. Understanding the nature of service users' adaptation to such an intensive therapeutic approach over time and the way in which their sense of self is challenged and can be protected is critical in further developing the EIS model.