There is compelling evidence indicating that the number of psychiatrists in the United States is far short of the current need, especially in rural and poorer communities (

1,

2). Preliminary estimates place the shortage at around 45,000 psychiatrists, and all signs indicate that the situation will get worse in the future (

3). This shortage is happening at a time when the demand for psychiatric services is increasing significantly because of factors such as population growth, greater evidence for the treatability of mental illness, more efficacious medications, and social acceptability of mental illness conditions (

4). A larger number of returning war veterans and deteriorating economic conditions may also further increase the need for psychiatric services.

Unfortunately, the supply of psychiatrists has not kept up with the demand because of factors such as underfunding of psychiatric services by the government, reductions in hours worked by aging psychiatrists, and a general reluctance of incoming medical students to choose psychiatry as their area of specialization (

4,

5). Unlike other physicians, psychiatrists face some unique problems. Psychiatrists as a group are more vulnerable to vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue, and job burnout and have the highest rate of suicidal tendencies among male physicians (

6–

8). These issues can have a major impact not only on service delivery and quality of care but also on turnover rates among psychiatrists.

Experts have suggested various options as possible remedies for the shortage of psychiatrists, such as getting primary care physicians to absorb excess patients, training a greater number of advanced practitioner nurses and physician assistants, hiring locum tenens, and providing mental health care via the Internet. But each option has limitations associated with its cost, quality of service, or effectiveness in treating patients (

3,

5,

9). If implemented, these measures collectively could alleviate some of the shortage of psychiatrists, but in the long run it will be very difficult to bridge the gap in services without attracting more medical students to psychiatry and motivating the current crop of psychiatrists to see more patients and delay retirement.

Past research suggests that physicians' career satisfaction has a critical impact on the medical profession (

10–

17). Physicians who are satisfied with their careers are more likely to provide better health care and have patients who are more satisfied (

18,

19). Moreover, dissatisfaction among physicians of a particular specialization can lead to declining numbers of medical graduates in that specialty (

20,

21), increase in rates of medical errors related to job stress (

22), unionization (

23), strikes (

24), and even exodus from the medical profession (

25). Toward this end it is imperative that politicians, health policy makers, and medical school directors have a good understanding of the factors influencing the overall career satisfaction of psychiatrists. The purpose of this study was to analyze the responses given by a nationwide sample of practicing psychiatrists so as to understand what it is that makes them “tick” and to identify areas needing reform, increased funding, efficiency, or political attention.

Discussion

Major studies examining career satisfaction of various physicians in the past have used the CTS, a community-based survey conducted over the telephone since 1996. Because the CTS had various well-documented limitations (

26), it was replaced by the HTPS in 2008, the secondary data used in our study. This 2008 nationwide survey addressed many contemporary physician care policy issues not addressed by the CTS, such as threat of malpractice lawsuits, and also formed a baseline for subsequent HTPS surveys to be conducted at a regular interval in the future.

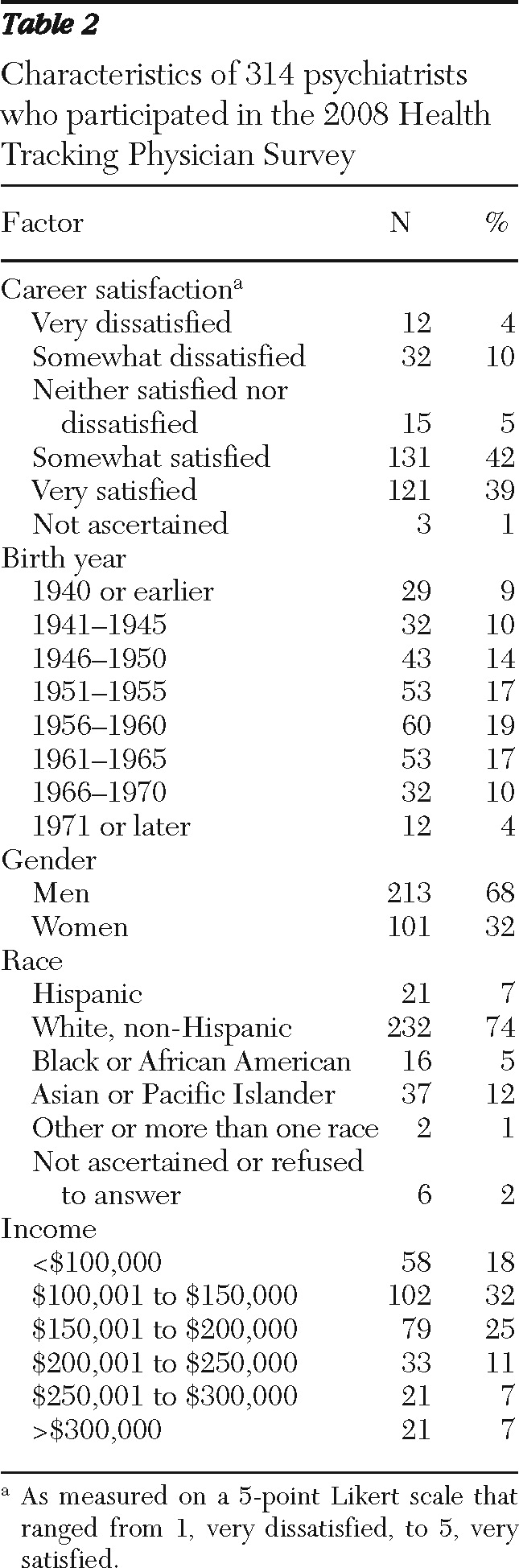

In our study 33% of the psychiatrists were born in or before 1950. Thus it is very likely that this cohort group will trim their practice hours or even retire in the coming decade. This is of concern because recent articles on the state of the psychiatry profession have highlighted the acute shortage of psychiatrists and the difficulty in obtaining mental health services in the United States (

3,

4,

9). A recent study that used the CTS found that two out of three primary care physicians reported that they could not obtain mental health services for some of their patients (

27). The current shortage of nearly 45,000 psychiatrists is likely to get worse when the psychiatrists born before 1950 start retiring or cutting down their services.

The shortage of psychiatrists is likely to get worse at a time when the need for certain specialties such as geriatric psychiatrists is likely to go up (

5). We cannot expect more medical students to choose to specialize in psychiatry because the average salary of psychiatrists is considerably less than some of the other medical specialties. In addition, many medical schools have cut down on training programs for potential psychiatrists because of cuts in federal funding (

5). Some experts have suggested that primary care physicians pick up the slack (

9). But primary care physicians are also in short supply and have to deal with a large variety of illnesses (

3). Other suggestions include increasing the number of advanced practice psychiatric nurses and physician assistants (

3). In addition, doctors of psychology can also be authorized to write prescriptions (

9). Some even suggest the use of telemedicine, so that psychiatrists can treat their patients over the Internet (

9). Steps also need to be taken to ensure that adequate coverage of mental health professionals exists in areas of greatest shortage such as rural areas and the public sector (

1).

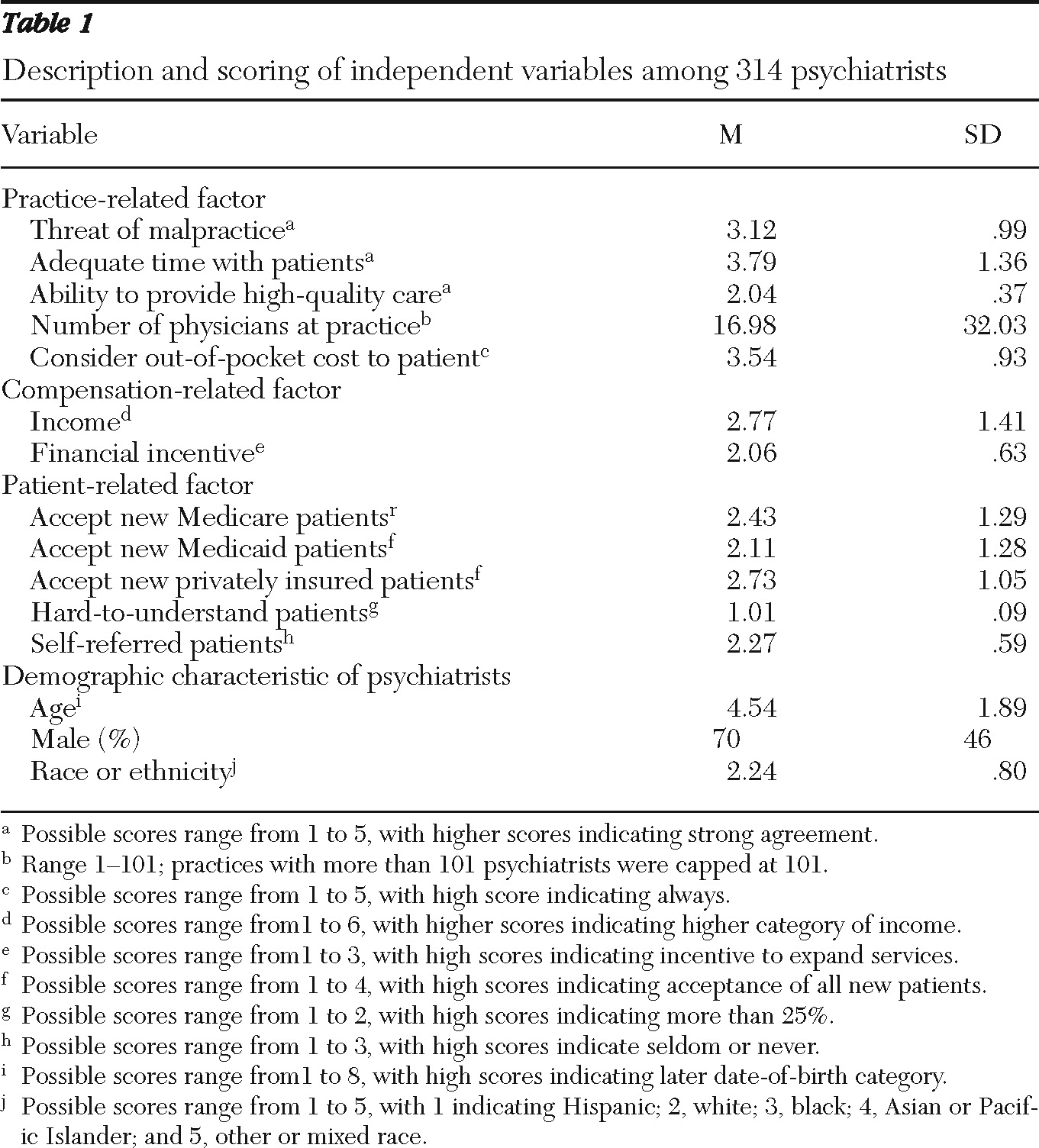

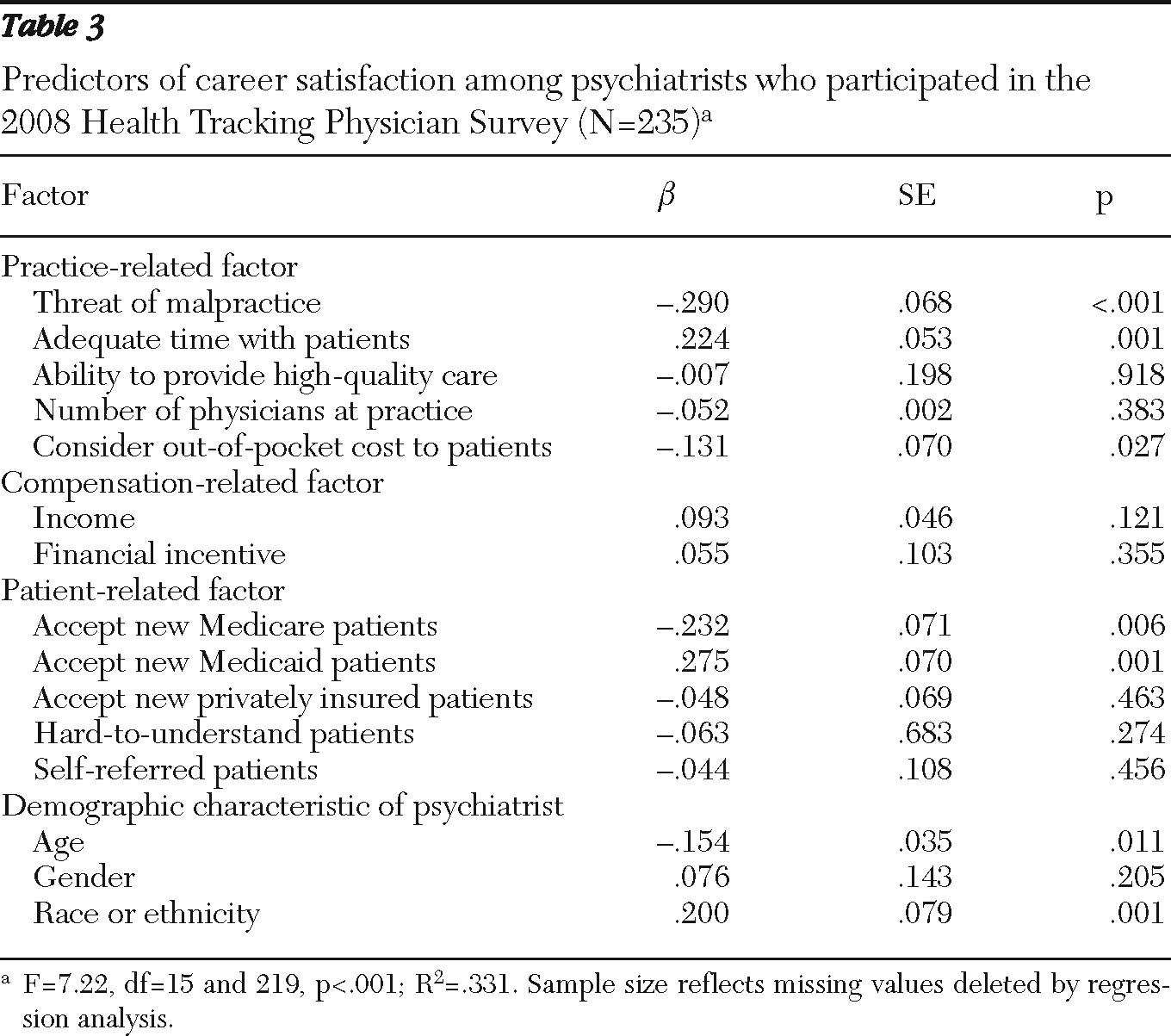

Among the practice-related factors, both threat of malpractice lawsuits and having to consider out-of-pocket cost to patients had a significant negative impact on career satisfaction. Each year, nearly 5% of psychiatrists face a lawsuit. Long-term consequences of malpractice cases include an increase in insurance premiums and limited opportunities for employment (

28). In addition, all settlements may be noted in the National Practitioner Database. A longitudinal study (1997–2002) based on the National Health Interview Survey uncovered some important disparities in the state of mental health care in the United States. The study reported that a large proportion of adults with significant psychological distress could not afford mental health care. In addition, large increases in costs for mental health care and medication over the years have resulted in a significant increase in the number of patients foregoing such services (

29). Unfortunately, this development has resulted in out-of-pocket costs dictating optimal treatment to patients receiving mental care. Thus it is not surprising that cost of out-of-pocket treatment had a significant negative impact on career satisfaction of psychiatrists.

On the other hand, adequate time spent with patients had a significant positive impact on career satisfaction. In a recent survey of psychiatrists by Epocrates, a manufacturer of mobile drug-reference tools, 27% of the respondents indicated that over the past five years, the length of patient visits had decreased (

30). Unlike other medical specialties, patients in psychiatry share intimate details about their lives. It is critical for psychiatrists to ensure that they have enough time with their patients to develop a rapport with them, ensure their trust, and build a lasting relationship (

5). Thus psychiatrists who perceived that they spent adequate time with their patients experienced higher levels of career satisfaction.

Unlike other factors, none of the compensation-related factors (income level and financial incentives) had a significant impact on the career satisfaction of psychiatrists. A study of career satisfaction of psychiatrists and surgeons in Canada reported that compared with surgeons, psychiatrists report a higher level of satisfaction with the process of determining pay rates (

31). In addition, previous studies have shown that a balance between personal and professional life is very important to psychiatrists (

31).

Among the patient-related factors, psychiatrists who worked in practices accepting new Medicare patients reported significantly less career satisfaction than those who worked in practices that did not. Most of the people under Medicare coverage are 65 years old or older. Medicare also covers people with disabilities who qualify for Social Security. For most mental health services, Medicare has high copayments or coinsurance and has been criticized by physicians for low reimbursement rates and too much paperwork (

32,

33). On the other hand, psychiatrists who worked in practices that admitted new Medicaid patients reported significantly higher levels of career satisfaction than those who worked in practices that did not. Medicaid is an entitlement program provided jointly by the federal and state governments, where the federal government sets the framework for the program and the states decide the eligibility requirements and payment rates. Medicaid provides benefits for low-income families and is a major source of funding for public mental health systems. Most of the Medicaid programs have nominal or no copayments.

It is important to note that since 2008, when the data used in this study were collected, there have been major assaults on Medicaid funding at the state and federal levels. In addition, the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will allow an additional ten million Americans with income up to 133% of the poverty level to become eligible for mental health coverage through Medicaid. That may make Medicaid one of the largest items in many state budgets. States already facing budget shortfalls will be forced to make cuts in other services to meet this obligation. A number of states have filed lawsuits to nullify the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The act also extended a 5% increase in Medicare payment rates for outpatient psychotherapy until the end of 2010. All these changes that have occurred since 2008 may have an impact on the results of our study.

Age had a significant impact on the career satisfaction of psychiatrists—that is, older psychiatrists tended to be more satisfied than younger psychiatrists. Previous research has shown a direct relationship between career satisfaction and outcomes such as better health care service, more satisfied patients (

18,

19), and exodus from the medical profession (

25). Our data do not allow us to determine specifically what might keep older psychiatrists from practicing longer or lead to earlier retirement. Previous research suggests that compared with younger cohorts of psychiatrists, older cohorts of psychiatrists report less burden from their patients (

34). In addition, older cohorts of psychiatrists were less likely than younger cohorts to perform research, teach, do hospital rounds, or hold university appointments. This decrease in job demands may explain the higher levels of satisfaction among older psychiatrists.

Our results also indicate that race and ethnicity had a significant impact on career satisfaction. Hispanic and African-American psychiatrists reported lower levels of career satisfaction than white, non-Hispanic psychiatrists. Previous research on underrepresented minority faculty in medical schools found that because underrepresented minority faculty had a higher debt load than peers in nonminority groups, underrepresented minority faculty were more likely to have more clinical responsibilities, to have less research time, and to moonlight to supplement their income (

35). It is possible that similar issues may have had an impact on career satisfaction of minority psychiatrists who were not faculty in medical schools. Hispanic and African-American psychiatrists accounted for only 12% of our sample. Previous research has indicated that African-American and Hispanic patients prefer to seek treatment from physicians of their own race (

36). In addition, minority physicians are more likely to locate their practice in underrepresented areas (

37).

Steps need to be taken to encourage more African-American and Hispanic medical students to become psychiatrists. One example of such a program is the Program for Minority Research Training in Psychiatry funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Another useful program is the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's Minority Fellowship Program, which provides grants to encourage and facilitate the doctoral and postdoctoral development of psychiatrists from ethnic and racial minority groups. However, in terms of decision to retire, one major factor that is not dealt with in the study is the financial aspirations and overall financial situation for the physician. It is very likely that many psychiatrists of retirement age continue to work because they cannot afford to retire.

This study has various limitations. The secondary data used in this study were self-reported. As with secondary data sets, the variables used in the study were identified and developed by the primary researchers and not by the authors of this study. Thus variables of interest, such as support at workplace, organizational culture, and types of rewards, could not be included in this study. The HSC in its public use data included physicians who identified their primary specialty as psychiatry, addiction medicine, or pediatric psychiatry under the general heading of psychiatrists. The data set does not allow us to differentiate them into the three categories. Future research can address these issues. Despite these limitations, this study has important implications for health care policy makers, health care educators, and future psychiatrists.