It is imperative to evaluate the management of common mood and anxiety disorders in primary care (

1,

2). The prevalence of these disorders is high at this level of care (

3–

5), and we must consider the high financial, physical, and emotional toll associated with these conditions, especially if left untreated (

6), and recent advances associated with their treatment in the primary care setting. Several studies have focused on the management of mood and anxiety disorders in primary care. Most of these studies have focused primarily on patient characteristics and neglected to take into consideration physician characteristics. These studies have shown that in addition to psychiatric diagnosis (

7), older adults, women (

8,

9), individuals with greater medical morbidity (

10), individuals of higher socioeconomic status (

11), and individuals of the majority group are more likely to use psychotropic medications or receive guideline-concordant treatment (

12). Lack of culturally appropriate services (

13), physical and financial barriers (

14), the stigma associated with mental illness (

15), and treatment preferences for counseling rather than medication (

16) may be partially responsible for these variations.

Other studies have focused primarily on physician characteristics associated with the management of mood and anxiety conditions in primary care (

17,

18). For instance, a study conducted in Israel found that family medicine physicians were more likely to manage depression by themselves compared with internal medicine physicians (

19). Only a few studies examined both physician and patient characteristics, but most of these studies did not conduct multilevel analysis to distinguish patient- and physician-level characteristics. One study found lower levels of adherence to psychotropic medications especially among patients of high-prescribing physicians (

11). Other studies found that patients whose physicians used guideline-concordant follow-up (

20) or provided greater educational information concerning the medications (

21) were more likely to adhere to their medication regimen.

There is a growing body of research arguing that multilevel analysis that takes into consideration both physician and patient characteristics is required for adequate understanding of clinical management in primary care (

22). Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyze the role of patient and physician characteristics associated with the purchase of antidepressant and antianxiety medications in Israel, a country that has a universal health care system and provides a comprehensive uniform basket of services that includes psychotropic medications but not psychotherapy (

23).

On the basis of past research (

25–

28), we expected older adults, women, and Israeli Jews to have a higher probability of purchasing antidepressant and antianxiety medications compared with Israeli Arabs. In addition, on the basis of a previous study regarding primary care physicians in Israel (

19), we expected a higher probability of purchasing among patients served by physicians with a specialty in family medicine.

Methods

The study received institutional review board approval from the Helsinki Committee of Clalit Health Services. We randomly sampled 30,000 primary care patients over the age of 22 as of January 2006 from Clalit Health Services' computerized medical registry.

Measures

Clalit Health Services uses a computerized medical registry that contains both patient and physician data. All physicians' visits are recorded in this registry and are matched with pharmacy data according to unique patient and physician IDs assigned to all Israelis.

We extracted data regarding whether or not an antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitor, and serotonin-norephinephrine reuptake inhibitors) or antianxiety medication (benzodiazepine and other hypnotics) was purchased at least once between January and December 2006.

Patient-level predictors

Demographic information.

From patients' self-report on initial visit, age, gender, birth country, and number of years in Israel were recorded in the registry.

Charlson Comorbidity Index.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index reflects both the number and seriousness of the patient's medical conditions in order to predict mortality (

29). This score is calculated by Clalit Health Services' medical division for all primary care patients and is adjusted for age.

Somatic diagnosis.

We constructed a list of common nonpsychiatric somatic conditions for which antidepressant or antianxiety medications are indicated on the basis of the medical literature (

30–

34). These conditions are specified in Clalit Health Services' computerized system as osteoarthritis of the spine, arthralgia, back symptoms, lower back pain, lower back pain with radiation, back disorders unspecified, backache, psychogenic backache, backache with radiation symptoms, chronic arthritis, headache, headache not otherwise specified, tension headache, abdominal pain, low abdominal pain, insomnia not otherwise specified, insomnia of nonorganic origin, psychogenic sleep disorder, sleep disorder, malaise, malaise and fatigue, fatigue, and giddiness and dizziness. The presence of any of these diagnoses was classified as somatic diagnosis.

Psychiatric diagnosis.

Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, and somatoform disorders were included under this category, using

ICD-10 codes. We excluded posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder because our aim was to focus on psychiatric conditions that are within the mandate of Clalit Health Services' primary care physicians (

35) rather than psychiatrists.

Socioeconomic status.

Socioeconomic status (low, medium, high) was based on the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics classification (

36). Although these data are available at the primary care clinic level, it is considered a good proxy of patient socioeconomic status (

37,

38). The vast majority of patients are registered in neighborhood clinics; thus the socioeconomic status of clinics reflects that of the patients' place of residence.

Population group.

Individuals were classified as Arabs or Jews on the basis of Clalit Health Services' classification of primary care clinics into locations that serve at least 70% Israeli Jews versus Israeli Arabs. Although these data are available at the primary care clinic level, they are considered a good proxy of patient ethnicity, given Israel's highly segregated nature (

39).

Physician-level predictors

Physicians' age, gender, place of birth, number of years in the country, number of years of experience, and specialty (none, family, or other) were available from employee records.

Analysis

We first conducted univariate and bivariate analyses. Next, we conducted multilevel analysis, with patient-level data representing the first level of predictors (patient age, gender, socioeconomic status) and physician-level data (physician age, gender, number of years in the country) representing the second level. The outcome variable was whether or not a patient purchased antidepressant or antianxiety medications at least once in 2006.

In the first step of the multilevel analysis, we used an empty model with physician as a random effect. This model estimated the outcome per physician rather than per patient. The intraclass correlation (ICC) scores that resulted could range from 0% to 100%, and they reflected the degree to which patients of the same physician were more similar to one another than patients of other physicians. Thus the ICC indicated the proportion of the total variance that was due to differences between physicians. If the ICC was relatively large, a multilevel analysis was justified. However, a relatively low ICC did not justify a multilevel analysis, and analysis instead considered only patient-level variables (level 1). As a rule of thumb, ICCs of .05, .10, and .15 represent small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (

40).

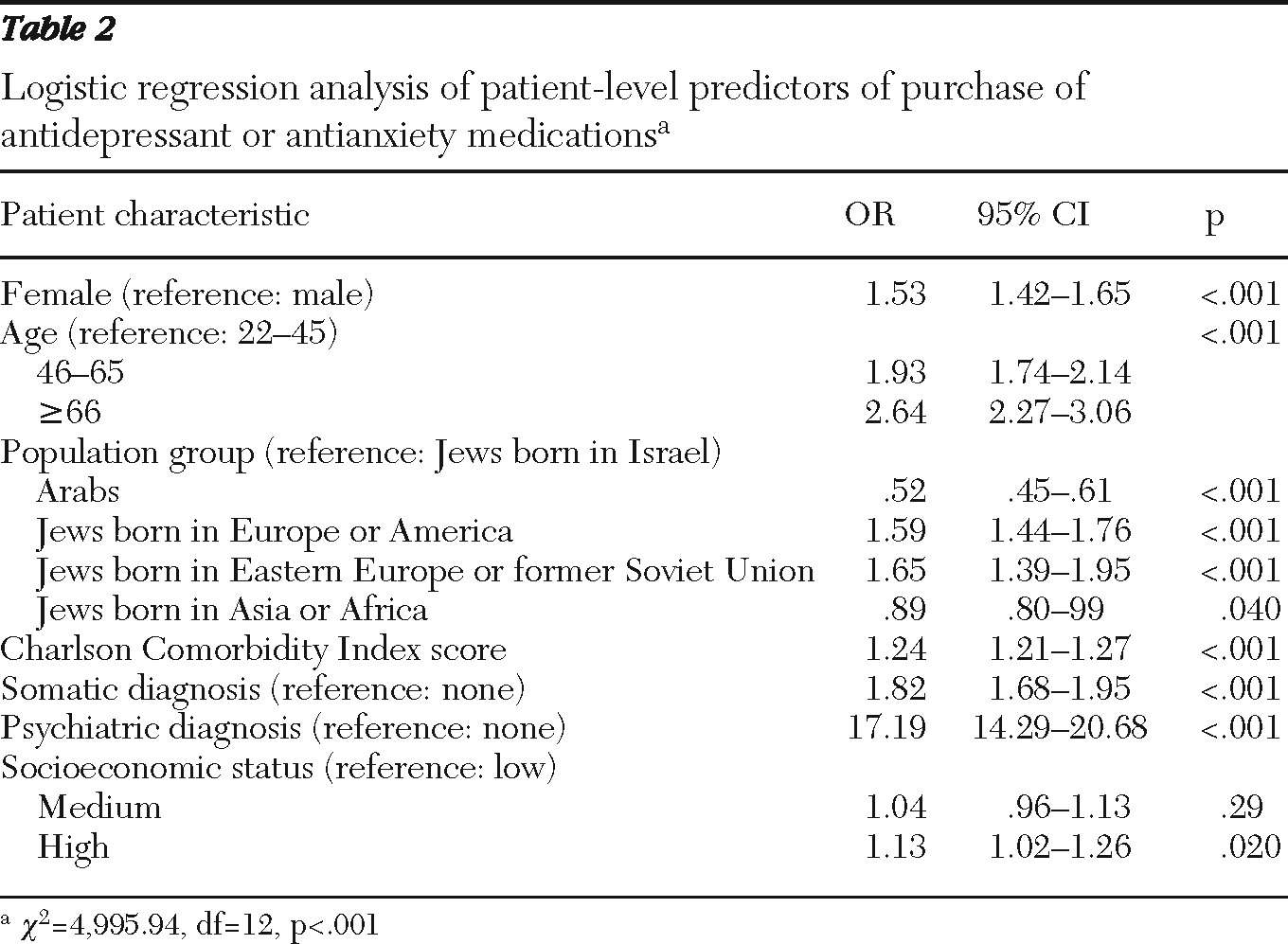

After calculating the ICC (which was.05), we conducted a logistic regression with purchase of antidepressant or antianxiety medications as an outcome. Only significant patient-level predictors (p<.05) identified in bivariate analyses were entered into the model.

Results

Of the 30,000 randomly selected patients, 591 died in 2006 and 4,446 individuals had incomplete physician data; these categories were not mutually exclusive. Thus the final sample consisted of 25,092 primary care patients, listed with 1,418 physicians working in 850 clinics all over the country. There were significant differences between those excluded from analysis because of death or missing physician data and the final sample. Those excluded from analysis were more likely to purchase antidepressant or antianxiety medications compared with the final sample (N=1,016, 20%; N=4,762, 19%, respectively; p=.003). In addition, those excluded from analysis were more likely to be older than 66 (N=1,271, 26%; N=4,806, 19%, respectively) and less likely to be between 46 and 65 (N=1,428, 29%; N=8,801, 35%, respectively; p<.001), had a higher mean±SD Charlson score (2.1±2.8 versus 1.7±2.1, respectively), and were less likely to have a somatic diagnosis (common nonpsychiatric somatic conditions for which antidepressant or antianxiety medications are indicated) (N=1,397, 28%; N=8,474, 34%, respectively; p<.001) compared with the final sample. Those excluded were also more likely to be of high socioeconomic status (N=1,151, 24%; N=4,514, 18%, respectively) and less likely to be of low socioeconomic status (N=1,762, 36%; N=10,494, 42%, respectively; p<.001) compared with the final sample. Finally, those excluded were less likely than the final sample to be Jews born in Israel (N=1,913, 39%; N=11,093, 45%, respectively) and more likely to be Arabs (N=851, 17%; N=3,639, 14%, respectively; p<.01), compared with the final sample (

Table 1).

Overall, 4,762 (19%) of the sample purchased antidepressant or antianxiety medications in 2006. There were significant differences between those who purchased medications and those who did not for all patient-level variables, with the exception of years in Israel. Women, older patients, those with a psychiatric or somatic diagnosis, those with greater medical comorbidity, and those of higher socioeconomic status were more likely to purchase antidepressant or antianxiety medications. Israeli Arabs were less likely to purchase medications, and Israeli Jews born abroad (immigrants) were more likely to purchase medications compared with Jews born in Israel (

Table 1).

Table 2 presents results of the logistic analysis, showing that women, older adults, those with greater medical comorbidity, and those with a psychiatric or somatic diagnosis were more likely than others to purchase medications. Jews born outside the country (with the exception of those born in Asia or Africa) were more likely than Jews born in Israel to purchase medications. In contrast, Arabs and Jews born in Asia or Africa were less likely than Jews born in Israel to purchase medications. Finally, those of higher socioeconomic status were more likely to purchase medications.

Discussion

This study evaluated the purchase of antidepressant or antianxiety medications in Israel by using medical registry data of the largest health care fund in Israel. The most notable finding was the high rate of antidepressant or antianxiety medications purchased (4,762; 19%) relative to the low rate of documented relevant psychiatric diagnoses, which amounted to 865 patients (3%) in the entire sample and 678 (14%) of those purchasing psychotropic medications. This overall rate of 3% likely is an underestimate given epidemiological studies that have shown much higher prevalence rates of psychiatric conditions in primary care (

28). Thus, similar to past research (

4), this study clearly demonstrated a tendency to underrecord mental disorders in primary care. This may be due to patient-related or physician-related causes such as the stigma associated with psychiatric illness (

41–

44). Although the reported rates of purchase seem to coincide well with general estimates of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in primary care (

3–

5), the use of antidepressant and antianxiety medications is also indicated for nonpsychiatric conditions. Thus undertreatment may prevail in this population.

As expected, having a psychiatric diagnosis was the best predictor of antidepressant or antianxiety medications. Nevertheless, the presence of somatic diagnosis based on nonpsychiatric symptoms, such as pain or insomnia, was also a strong predictor of purchase. In fact, although only 14% of those purchasing antidepressant or antianxiety medications had a relevant psychiatric diagnosis, 51% of purchasers had a nonpsychiatric somatic diagnosis. Therefore, it is possible that some mental conditions were labeled as somatic either erroneously or due to the stigma of mental illness. Further research is needed to clearly verify the source of this finding and to better tailor educational interventions to improve the diagnosis of mental illness and potentially improve the treatment quality of depression and anxiety in primary care.

Rates of medication purchase identified in this study were substantially higher than prevalence rates obtained by self-report measures in a previous national study (

27,

45). The stigma associated with the use of psychotropic medications might be responsible for a lower rate found in past research that was based on self-report data. This should be taken into consideration in future epidemiological studies concerning psychotropic use.

Another interesting finding is population group differences in the purchase of psychotropic medications. Israel has a universal health care system that covers psychotropic use. Yet, those of higher socioeconomic status were more likely to purchase medications, potentially because socioeconomic status is a proxy of education and reduced stigma of mental illness. In addition, consistent with past research (

45), the purchase of medications does seem to be higher among immigrants (with the exception of those born in Africa or Asia) and lower among Israeli Arabs and immigrants from Asia and Africa (

25,

26). Research has consistently shown that migration is a stressful situation that often has deleterious effects on one's mental health (

46,

47). This study may provide further support to these findings because it demonstrates that immigrants, with the exception of those coming from Asia or Africa, are more likely to purchase antidepressant or antianxiety medications. Alternatively, this may reflect a cultural preference toward psychotropic use in these particular groups.

Israeli Arabs were substantially less likely than Jews born in Israel to purchase medications, with multivariate analyses controlling for all other demographic and clinical variables. These findings are particularly intriguing given past research that found substantially higher levels of depression among Israeli Arabs than among Israeli Jews (

48). Low levels of psychotropic purchase may be explained by culturally incompatible services offered to this population (

49). This may also be due to the stigma of mental illness in this population (

50,

51). Further efforts to improve culturally sensitive services and to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness are indicated particularly for Israeli Arabs. It is possible that Israeli Jews born in Asia or the Middle East may also benefit from such interventions. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that those groups in the population who were less inclined to purchase antidepressant or antianxiety medications used other modalities to manage mental distress. However, because psychotherapy is not included in the basket of services provided by universal health care funds in Israel and because community services that offer psychotherapeutic interventions are overburdened by demand (

52), it is unclear whether disadvantaged groups have access to other formal modalities to address their mental health needs. Finally, it is possible that the use of informal services, such as religious counseling or assistance by family and friends, successfully replaces formal services in these groups.

An interesting lack of significant finding should also be noted. In contrast to past research adamantly advocating multilevel analysis of primary care data (

22), we found physician-level variations to be too low to justify such an analysis. This is also in contrast to past research that found physician characteristics to be of importance in the treatment of mental illness (

17,

18). Possibly, the focus on purchase rather than prescription is partly responsible for this difference, because the purchase of medications likely is more dependent on patient characteristics than on physician characteristics. Although less common in Israel, the fact that many psychotropic medications are directly advertised to patients and not only to physicians may account for the findings (

53). Another explanation may be related to the implementation of guidelines and massive educational efforts of Clalit Health Services in the past few years to increase primary care physicians' awareness of and ability to treat depression and anxiety (

35). These efforts may have possibly reduced differences among physicians of varying specialties and experience levels.

Several limitations should be noted. Our study focused on the purchase of antidepressant or antianxiety medications in primary care and not on the treatment of depression or anxiety, which would include other important approaches, such as psychotherapy, appropriate follow-up and planning, and case management (

54). Because under current laws psychotherapy is not included in the basket of services provided by universal health care funds to primary care patients in Israel, data on these treatments are not recorded in Clalit Health Services' medical records, and thus we were unable to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the treatment of depression or anxiety in primary care. In addition, this study focused on the purchase of medications rather than on the prescription of medications. The focus on cross-sectional analysis does not allow for inferences about cause and effect. Furthermore, the individuals excluded from analysis were substantially different from the remaining sample, suggesting that some groups may be underrepresented. Finally, we did not have data on physicians' ethnic origin, a variable that might be related to patients' purchasing behaviors.