More than 500,000 people with a mental illness excluding dementia are estimated to reside in U.S. nursing homes (

1). Although dementia is highly prevalent among nursing home residents, current trends show that the proportion of individuals admitted to nursing homes with mental illness has overtaken the proportion with dementia (

2). Except for instances in which an individual requires 24-hour skilled nursing care because of major physical health care needs, physical disability, or severe cognitive impairment, nursing facilities are not considered the most appropriate setting for persons with mental illness.

Most research on mental illness in nursing homes has focused on comorbid depression among older nursing home residents (

3–

5), and little is known about the medical conditions and functional status of persons with other mental illnesses newly admitted to nursing homes. This study of newly admitted nursing home residents with major mental illness examined whether differences existed in the prevalence of comorbid medical conditions and functional impairment between younger and older individuals and among individuals with different psychiatric diagnoses.

Methods

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' national registry of nursing home resident assessments from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) were used to compare comorbid conditions and functional impairments among newly admitted nursing home residents aged 18 and older with major mental illness. (

6). New admissions were defined as those residents with an admission assessment during calendar year 2008 for whom no MDS record existed in the registry as far back as January 1, 1999, implying that the admission was the person's first. Institutional review board permission was obtained for the study from Brown University.

Major mental illness was characterized as either schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression, in that order. For example, an individual with a diagnosis of both schizophrenia and depression was categorized in the schizophrenia group. Because the MDS does not include the primary reason for admission, a mental illness diagnosis can represent either a primary or secondary reason for admission.

The comorbid conditions identified were stroke, dementia (diagnosis of either dementia or Alzheimer's disease), Parkinson's disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, diabetes, obesity (body mass index >30), and severe cognitive impairment (Cognitive Performance Scale score≥4).

Functional characteristics included requiring assistance in transferring from surface to surface (“dependence in transfer”), activities of daily living, and low-care status. Limitations in activities of daily living were calculated using a scale from 0 to 28, with higher values indicating greater disability. Low-care status was met if a resident did not require physical assistance in any of the four late-loss activities of daily living (mobility to and from bed, transferring from surface to surface, using the toilet, and eating) and was not classified in either the Special Rehab or Clinically Complex Resource Utilization Group (Rug-III) (

7).

Individuals were stratified by psychiatric diagnosis and age (65 and older or younger than 65) and compared on the basis of demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and functional impairments. Statistical inference tests comparing the groups were not conducted, given that the data represented the population of interest (all new admissions to nursing home with a major mental illness diagnosis in 2008).

Results

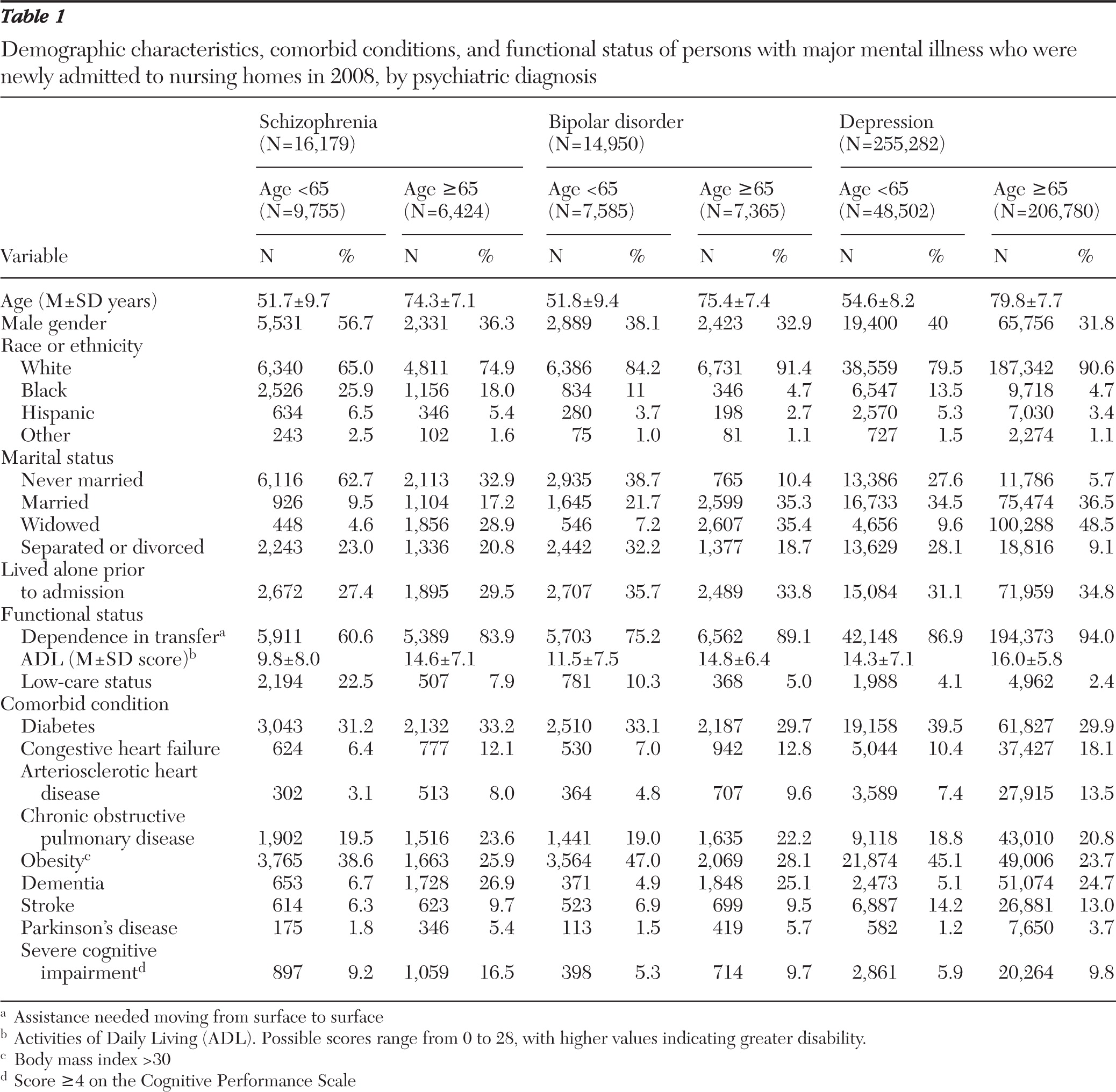

The results of the study are summarized in

Table 1. A total of 286,411 persons were newly admitted to nursing homes with major mental illness. Of those, 5.6% (N=16,179) were admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 5.2% (N=14,950) with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and 89.2% (N=255,282) with a diagnosis of depression. Most (N=9,755; 60.3%) persons with schizophrenia were younger than 65, whereas the proportion of elderly (N=7,365) and nonelderly persons (N=7,585) with bipolar disorder was the about the same. In contrast, the vast majority (N=206,780; 81%) of persons with depression were aged 65 and older.

Among persons with schizophrenia, those younger than 65 had lower rates of severe cognitive impairment, congestive heart failure, and arteriosclerotic heart disease than their elderly counterparts. A higher proportion of people with schizophrenia younger than 65 met the criteria for low-care status. Newly admitted individuals with depression younger than 65 were more likely to have diabetes, heart disease, and stroke and to have greater functional impairments, including dependence in transfer and needing more assistance with activities of daily living compared with younger individuals with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. In contrast, rates of medical comorbidity were similar across diagnostic groups among persons aged 65 and older.

Discussion

The majority of persons newly admitted to nursing homes with schizophrenia were younger than 65, and many of them lacked clinical indications for skilled nursing level of care. These findings may reflect an inadequate community support service system for nonelderly adults with schizophrenia.

According to the federal government, under no circumstances should a person with mental illness be forced to live in a nursing home if he or she could live in the community with adequate supports. Use of the federally mandated Preadmission Screening and Resident Review (PASRR) aims to ensure that nursing home placement is appropriate for persons with mental illness (

8). Although use of PASRR is associated with an overall decline in nursing home admissions for persons with mental illness (

9), state compliance with PASRR has been problematic (

10,

11).

The higher rates of medical conditions among nonelderly adults with depression and among elderly adults across psychiatric diagnoses suggest a need for integrated psychiatric and medical care in nursing homes. Most nursing homes do not have access to mental health providers. In a recent review of the literature on the quality of mental health care in nursing homes, Grabowski and colleagues (

12) found that the treatment of mental health problems in nursing homes is often substandard. The American Geriatrics Society and the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (

13) recommend setting policies that require nursing facilities to establish formal agreements with consulting mental health providers for ongoing training, consultation, and treatment services.

There were two major limitations to this study. First, the study was based upon the validity of the MDS clinical and functional assessment data. The validity of MDS data has been questioned by many, both because providers have reason to inflate impairment to maximize Medicare and Medicaid payment and because of poor and inconsistent training of nursing home assessors (

14). However, studies have generally confirmed the reliability and validity of these data, with some variability across nursing homes (

15). Second, the sample was constructed on the basis of first-time nursing home admissions rather than on a single cross-section of residents at a given point in time. As such, the data examine the flow of residents into nursing homes rather than the number of people with mental illnesses receiving services.

Conclusion

Three-fifths of individuals with schizophrenia newly admitted to nursing homes were younger than 65, and many lacked clinical indications for nursing home care. In contrast, four-fifths of new admissions with depression were 65 or older and were characterized by high rates of medical comorbidity regardless of their age. Findings suggest the need for effective models of supported housing, psychosocial rehabilitation, and integrated health care for adults with mental illness at high risk of disproportionate placement in nursing homes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Drs. Cai and Mor were supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) Program Project AG027296. Dr. Grabowski was supported by career development award K01-AG024403 from the NIA. Dr. Bartels was supported by mid-career investigator award 2K24MH066282 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.