Several lines of evidence suggest that psychotic depression is a distinct disorder. Recurrence of psychotic depressed episodes in patients with psychotic depression suggests that the disorder runs “true to form” (

1–

7). Two family studies (

8,

9), using direct interviews of family members, found an increased incidence of psychotic depression in first-degree relatives of probands with psychotic depression. Twelve treatment studies, reviewed elsewhere (

10), indicate that patients with major depression and psychosis are much less likely to respond to tricyclic antidepressants alone than their nonpsychotic depressed counterparts.

A variety of biological variables have been examined in psychotic depression (

11). Cortisol secretion is the most frequently studied measure, and the dexamethasone suppression test (DST) (

12) is the method most frequently used. Although hypersecretion of cortisol has been reported in psychotic depression, results have been mixed, with several studies failing to find a significant difference in rates of nonsuppression of cortisol on the DST. The current study was undertaken to review these studies, perform a meta-analysis of the findings, and determine the status of the DST in psychotic depression. Because nonsuppression of cortisol on the DST has also been associated with melancholic depression and this association might explain the findings in psychotic depression, we also reviewed studies of the DST in patients with melancholic or endogenous depression.

METHOD

We reviewed the literature to find studies reporting DST results in psychotic and nonpsychotic patients. These studies were examined to determine that 1) the studies included independent, nonoverlapping groups of patients, 2) the criteria for major depression were specified, and 3) the methods used to assess the psychotic or nonpsychotic status of the patients were clear. We also reviewed these studies to determine the method of DST administration and whether patients for whom the test was inappropriate were excluded (

12). Although there was some variability in the actual DST methods used, the methods were valid and relatively comparable.

Studies of the DST in melancholic depression were also reviewed. Again we determined that the groups of patients were independent, that the melancholic group was compared with patients who had nonmelancholic major depression (rather than those with other psychiatric disorders or normal control subjects), that a systematic method of DST administration was described, that appropriate exclusions were used, and that the number of patients who were nonsuppressors was presented for each group. The studies varied in the manner in which melancholic or endogenous depression was defined. The DSM-III criteria for melancholia and the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (

13) for endogenous depression were the most common methods, but in one case ICD-8 criteria were used, and another study used clinical criteria described by the investigators.

We used the Mantel-Haenszel test (

14) for the meta-analyses, following the recommendation of Emerson (

15). It was previously used by the American Psychiatric Association's Task Force on Laboratory Tests in Psychiatry (

16) and is the most common meta-analytic method used for dichotomous data in the medical literature. To examine whether the results were consistent from study to study, we determined the homogeneity of the effect size in the samples with the original Mantel-Haenszel method (

14). This refers to the variability of the difference between rates of nonsuppression in psychotic and nonpsychotic patients from study to study. If the effect sizes differed significantly, we used the DerSimonian and Laird method (

17), which does not assume a fixed effect size.

RESULTS

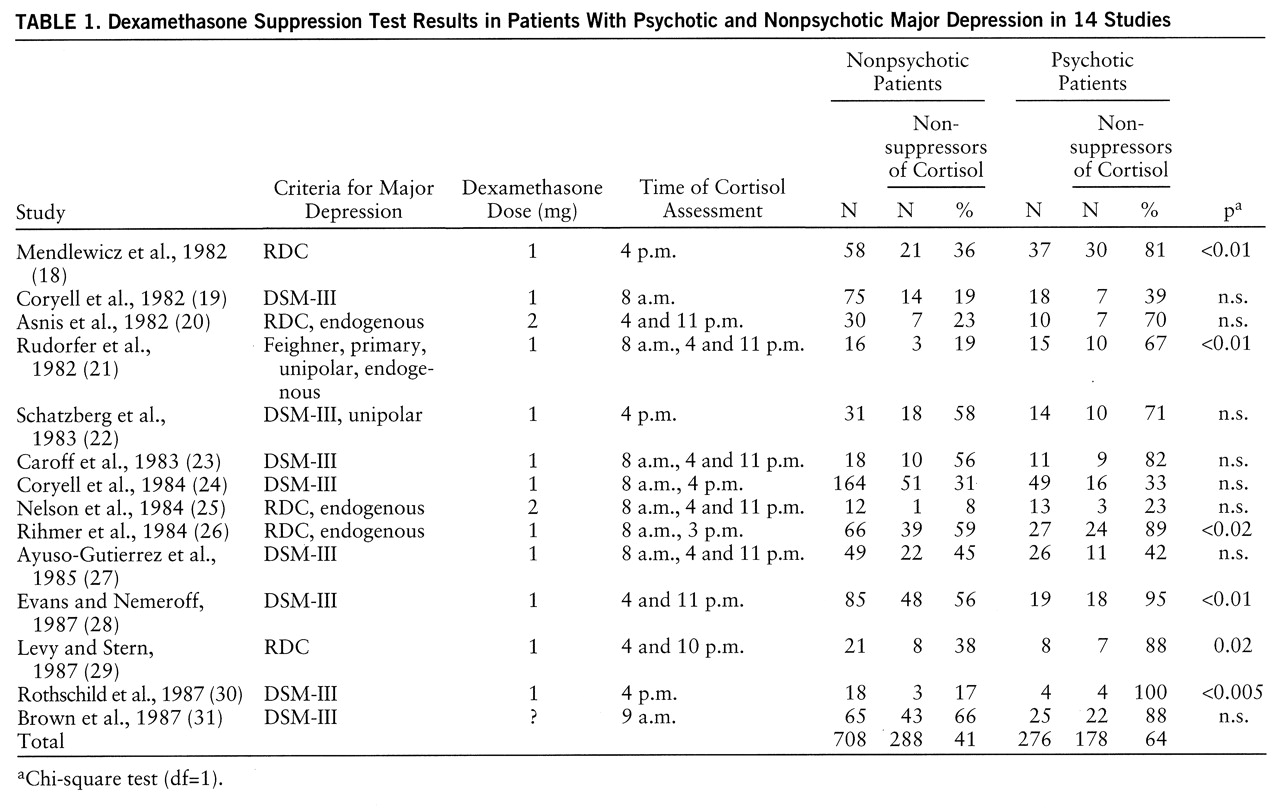

Fourteen studies (

18–

31) that involved independent groups of psychotic and nonpsychotic depressed patients met our criteria and were included in the analysis (

table 1). All of these studies used either the RDC (

13), the Feighner criteria (

32), or the DSM-III criteria for major depression. Most study groups consisted of inpatients, but two studies (

22,

30) included both inpatients and outpatients. All studies observed exclusions for the DST, usually those described by Carroll and associates (

12). The dexamethasone dose and timing of cortisol samples varied across studies (

table 1).

These studies included a total of 276 psychotic and 708 nonpsychotic depressed patients. The overall rates of nonsuppression of cortisol were 64% for the psychotic depressed patients and 41% for the nonpsychotic group. The Mantel-Haenszel analysis of the 14 studies demonstrated a highly significant probability that the greater rate of nonsuppression in the psychotic depressed patients was not a chance finding (χ2=47.43, df=1, p<0.001; odds ratio=3.0; 95% confidence interval=2.2–4.1). An analysis of the homogeneity of the effect size was nonsignificant (χ2=11.39, df=15, p=0.58), indicating that the effect size did not differ significantly from study to study.

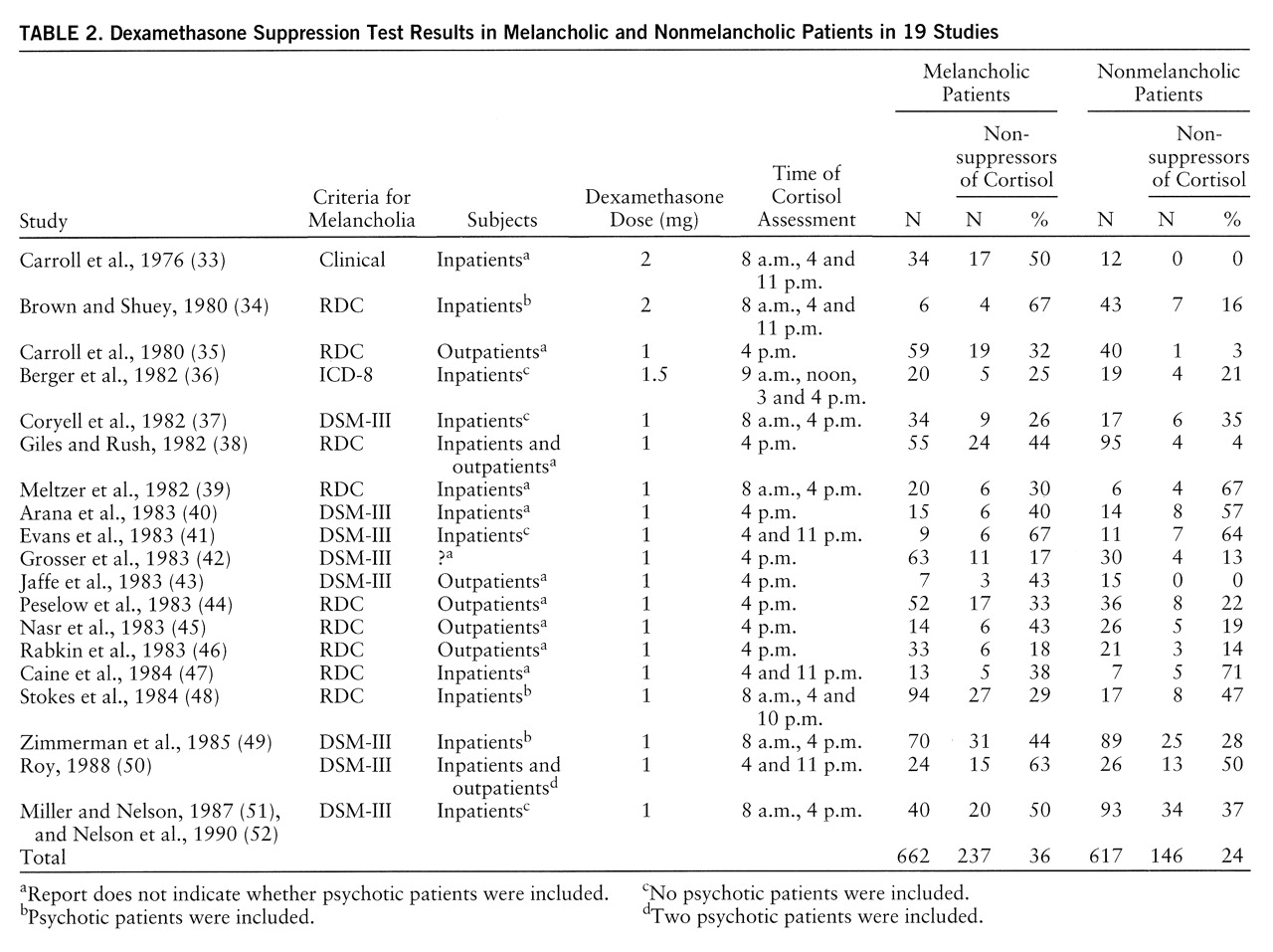

Nineteen studies (

33–

52) that compared the DST in melancholic and nonmelancholic patients were identified (

table 2). (Two study groups [51, 52] that partially overlapped were combined to eliminate duplication and were subsequently treated as a single group.) Of the 662 melancholic patients, 36% were nonsuppressors of cortisol on the DST; of the 617 nonmelancholic patients, 24% were nonsuppressors. An analysis of the homogeneity of the findings among the studies was significant (χ

2=44.44, df=18, p<0.001), indicating that the effect size varied significantly from study to study. Thus, we examined these data using the DerSimonian and Laird method. This analysis indicated that nonsuppression of cortisol was significantly more likely in melancholic depressed patients, but the magnitude of the probability was substantially lower than that for patients with psychotic depression (χ

2=4.84, df=1, p<0.03; odds ratio=2.0; 95% confidence interval=1.5–2.6).

The 19 studies of melancholia included both inpatients and outpatients, and rates of nonsuppression on the DST differed for these groups. The overall rate of nonsuppression in the five studies of outpatients only was 22% (N=68 of 303), while in the 11 studies of inpatients only, the rate was 36% (N=244 of 683). The difference between inpatients and outpatients was similar to that observed for melancholic and nonmelancholic patients. If inpatient/outpatient status was accounted for, melancholia was not associated with nonsuppression of cortisol on the DST. A DerSimonian and Laird meta-analysis of rates of nonsuppression limited to the 11 inpatient studies indicated that rates of nonsuppression did not differ significantly in melancholic and nonmelancholic patients: 38% (N=136 of 355) and 33% (N=108 of 328), respectively (χ2=0.11, df=1, p=0.74). Alternatively, among the melancholic patients, rates of nonsuppression in inpatients and outpatients showed a similar difference (38% versus 31%). It appeared that both melancholic status and inpatient status were associated with a moderate increase in cortisol nonsuppression; however, the combination of melancholia and inpatient status did not appear to significantly or substantially increase the rate of nonsuppression once either single variable was present. In nonmelancholic outpatients, the nonsuppression rate was low, 12% (N=17 of 138).

DISCUSSION

Although less than one-half of the studies of the DST in psychotic depression individually found significant differences between patient groups, all but one of the studies found a higher rate of nonsuppression of cortisol in psychotic depressed patients than in nonpsychotic depressed patients. Our meta-analysis demonstrated a very substantial probability that nonsuppression occurs more frequently in psychotic depression than in nonpsychotic depression. Further, the actual rate in psychotic depression, 64%, indicates that hypercortisolemia is a characteristic of most patients with psychotic depression. These findings support the distinction between psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression and are consistent with the hypothesis, advanced by Schatzberg and colleagues (

53,

54), that elevated cortisol levels may play a role in the pathophysiology of psychotic depression.

Several of the studies we reviewed noted that not only did the DST show nonsuppression of cortisol in psychotic depression, but the actual cortisol levels were quite high (

22,

28–

31). Some investigators (

22,

28,

29,

55) have suggested that a higher threshold between 11 and 15 µg/dl might be more specific and predictive for psychotic depression.

Because psychotic depression is a severe disorder, it might be questioned whether the differences in rates of nonsuppression on the DST between psychotic and nonpsychotic patients is explained by severity. First, it should be noted that in most cases, the comparison groups in the 14 studies consisted of melancholic inpatients whose illness was also reasonably severe. In six of the studies (

18,

20,

21,

26,

29,

30), the issue of severity was explicitly addressed. In each case, either severity was not associated with suppression/nonsuppression or multivariate analysis indicated that severity did not account for the difference in the rate of nonsuppression in psychotic and nonpsychotic depressed patients.

The studies of psychotic depressed subjects varied in the use of other subtyping restrictions (e.g., whether the subjects had endogenous, primary, or unipolar depression); however, in all but two studies, the comparison subjects were inpatients. The diagnostic issue that appeared to be most important was how schizoaffective disorder, other signs of schizophrenia, or mood-incongruent delusions were dealt with. In two of the studies with the lowest rates of cortisol nonsuppression (

19,

24), schizoaffective patients or those with “subtle signs of schizophrenia” were not excluded. In the second of these studies, 64% of the psychotic patients had mood-incongruent delusions. Ayuso-Gutierrez and colleagues (

27), in the only study with a lower rate of nonsuppression in the psychotic patients, noted that the eight patients with mood-incongruent delusions had a much lower rate of nonsuppression (12%) than the 18 patients with mood-congruent delusions (55%). The rate of nonsuppression in the patients with mood-congruent delusions was slightly higher than the rate in the nonpsychotic patients, consistent with the other 13 studies. Lower rates of nonsuppression have also been observed in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients and patients with atypical psychotic features (

53).

The meta-analysis of the differences between melancholic and nonmelancholic patients was clearly significant, but the effect size was not as large as it was for the psychotic/nonpsychotic distinction. Further, these studies varied with respect to inclusion of psychotic patients. Reports from four studies (

34,

48,

49,

50) indicated that psychotic patients were included, four studies (

36,

37,

41,

51,

52) excluded psychotic patients (or results were presented separately), and in 11 studies psychotic status was not specified. In the four studies that explicitly excluded psychotic patients (all were inpatient studies), rates of nonsuppression did not differ significantly in the 103 patients with endogenous depression (39%) and the 140 with nonendogenous depression (36%). It is possible that inclusion of psychotic patients (who are usually melancholic) contributed to the purported relationship between cortisol nonsuppression and melancholia. It seems even more likely that controlling for inpatient/outpatient status helps to explain the lack of difference between melancholic and nonmelancholic patients in these four studies.

Both inpatient status and melancholia were associated with a moderate increase in the rate of nonsuppression of cortisol, but because they covary, it was difficult to separate their independent associations with the DST results. It is probable that both variables are important, and both could reflect some underlying factor associated with hypercortisolemia.

In a study of 95 nonpsychotic inpatients, Miller and Nelson (

51) examined this question. Cortisol nonsuppression occurred in 43% (N=41) of these inpatients but was not significantly correlated with DSM-III melancholia, RDC endogenous depression, or severity. Seven individual symptoms were significantly correlated with nonsuppression of cortisol. These symptoms were examined to determine whether there were common factors that were related to hypercortisolemia. No common factors were found. Miller and Nelson (

51) reviewed 11 other studies (

34,

56–

65) that examined the relationship of individual symptoms to DST results. The most common symptom correlates of the DST were psychomotor change (both retardation and agitation) and sleep disturbance, followed by weight loss and somatic anxiety. Although these symptoms appear to be characteristic of melancholia, other symptoms also central to the concept of melancholia, such as loss of interest and lack of reactivity, were not frequently associated with nonsuppression. Further, these symptoms did not vary together, but were individually associated with the DST results. Thus, in our previous study (

51), in our review (

51), and in other reviews (

58,

66,

67), it has not been possible to identify a diagnostic syndrome or a common factor other than psychotic depression that relates to nonsuppression.

It might be questioned whether the lack of homogeneity of effect size in the 19 melancholia studies suggests flawed methods in some of the studies. There are other explanations, however, that appear to provide a satisfactory explanation for the lack of homogeneity. These studies included inpatients and outpatients, different criteria for melancholia, and different methods for performing the DST (for example, usually only one cortisol sample was obtained from outpatients).

The question also arises whether reports of rates of cortisol nonsuppression might be inflated because of the tendency not to report negative results (the “file drawer” issue). Although this is possible, it seems relatively unlikely. The DST has been studied over many years. After the initial positive reports, negative reports became worthy of publication. In fact, five groups of investigators (

37,

39,

40,

47,

48) reported negative results for the DST in melancholia (i.e., a higher rate of nonsuppression of cortisol in nonmelancholic patients). Further, most of the focus has been on the DST in melancholia; thus, reports on the relation of DST results to psychotic depression may be less biased. Given the strength of the association of nonsuppression on the DST with psychotic depression in the studies reviewed, we estimated that negative results from another 4,162 studies would have to be reported to render our findings statistically nonsignificant (

68).

CONCLUSIONS

These findings indicate that psychotic depression is the subtype of depression associated with nonsuppression of cortisol following administration of dexamethasone, and that nonsuppression of cortisol occurs in two-thirds of these patients. Nonsuppression is found in about one-third of melancholic patients and of inpatients, but if inpatient status is accounted for, the significance of the association between melancholia and nonsuppression is lost. In outpatients with major depression, the nonsuppression rate is low. Individual symptoms have been associated with nonsuppression, but no other subtypes or factors that explain the association of these symptoms with hypercortisolemia have been identified.

From a clinical perspective, nonsuppression of cortisol on the DST is of limited diagnostic usefulness. Often the diagnosis of psychotic depression is obvious. In patients for whom the diagnosis is questionable, however, a substantially elevated cortisol level after dexamethasone would be another piece of evidence favoring the diagnosis of psychotic depression. This test might be particularly useful in “near-delusional” patients with depression. Two studies (

69,

70) have noted that near-delusional patients respond less well to antidepressants given alone and may require combined antipsychotic and antidepressant treatment. In addition, this test may prove useful for assessing when a psychotic depressed patient has been adequately treated, because it has been suggested that the DST result reverts to normal with recovery of the patient and that failure to revert may predict suicide potential (

16). Roose and associates (

71) have reported that psychotic depressed patients are more likely to commit suicide, even when they appear to have improved. The use of the DST may help to determine whether a patient with psychotic depression has been adequately treated.

From a theoretical perspective, it has been suggested that hypercortisolemia may contribute to psychosis by enhancing dopamine activity (

53,

54). Several animal studies (reviewed elsewhere [53]) and two human studies (

72,

73) indicated that administration of glucocorticoids increases dopamine or dopamine metabolite levels in the CSF or plasma. Two studies of patients with psychotic depression (

30,

74) found a specific pattern of response to dexamethasone which differed from that of other patients or control subjects. Increased dopamine activity, as evidenced by elevated plasma dopamine levels (

30), elevated CSF homovanillic acid (HVA, the metabolite of dopamine) levels (

75–

78), and plasma HVA levels (

79,

80), has been linked to psychosis in depressed patients. Two studies (

81,

82) noted an increase in CSF HVA in depressed patients who became psychotic during antidepressant treatment, while in most patients HVA levels fell. These findings suggest that hypercortisolemia may enhance dopamine activity in some patients, and this change may contribute to psychosis. Further investigation of the role of hypercortisolemia in psychotic depression is warranted.