Ten years after the Chernobyl nuclear reactor accident (Ukraine, April 26, 1986), a dramatic increase in thyroid cancer among exposed children was demonstrated, but so far, no other serious health effects have been established (

1). The literature on disasters suggests that long-term mental health effects may have occurred as well, and that mothers with young children may be particularly vulnerable in this respect (

2). In the case of the Chernobyl disaster, two systematic studies have shown higher levels of psychological distress in the affected population, particularly among women (

3,

4). In an earlier article (

5) we reported a high prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders in the severely affected Gomel region in Belarus, with a significantly higher risk among evacuees and mothers with young children. In the present article we compare the results of the Gomel study with those of a study that was conducted 6 months later in the Tver region (Russian Federation), about 500 miles to the northeast. This region is similar in socioeconomic structure, population size, and cultural background but is not contaminated by fallout from Chernobyl.

The aim of the study was to test the hypotheses 1) that 6 years after the event, there would be more psychopathology in the exposed region after control for sociodemographic differences between the populations and 2) that being a mother with young children would constitute a risk factor in the disaster area but not in the control area.

METHOD

Because no population registers were available, a cross-section of the two populations was sampled at sites such as factories, collective farms, schools, and libraries throughout the regions (

5). In the Tver region, interview sites were matched as closely as possible to the interview sites in Gomel (

6). Participation took place on a voluntary and strictly confidential basis. In order to emphasize this, no further information was collected about nonresponders.

A two-stage design was used. During phase 1 a self-report questionnaire, including the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (

7), was administered. In Gomel 1,617 people participated in phase 1 (92% response); in Tver, 1,427 (88%).

In phase 2, a random stratified subsample, containing an oversampling of respondents with high General Health Questionnaire scores, was examined by a clinician using the Munich Diagnostic Checklist for DSM-III-R (

8). In Gomel 265 people participated in phase 2 (82% response); in Tver, 184 (65% response). Phase 2 assessment further included the Brief Scales for Anxiety and Depression (

9) and the Bradford Somatic Inventory (

10) for the assessment of psychosomatic distress. All questionnaires were found to have good internal consistency and reliability under the local circumstances (

6). A time frame of 1 month (“the last 4 weeks”) was used.

The results of phase 2 assessments were weighted back to their distribution in the phase 1 sample by using the sampling rates as weights. To enhance statistical power, DSM-III-R categories were combined into three main groups: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and any covered DSM-III-R diagnosis. Odds ratios and adjusted odds ratios (adjusted for potential confounding by sociodemographic variables) were calculated, with site of the study as the main predictor. Log likelihood ratios were calculated for all female subjects to assess whether adding the interaction between 1) being a mother with children under 18 years of age and 2) living in the affected region (Gomel) would significantly improve the fit of the model without the interaction term. The Bonferroni-Holm correction was used to adjust for multiple pairwise comparisons.

RESULTS

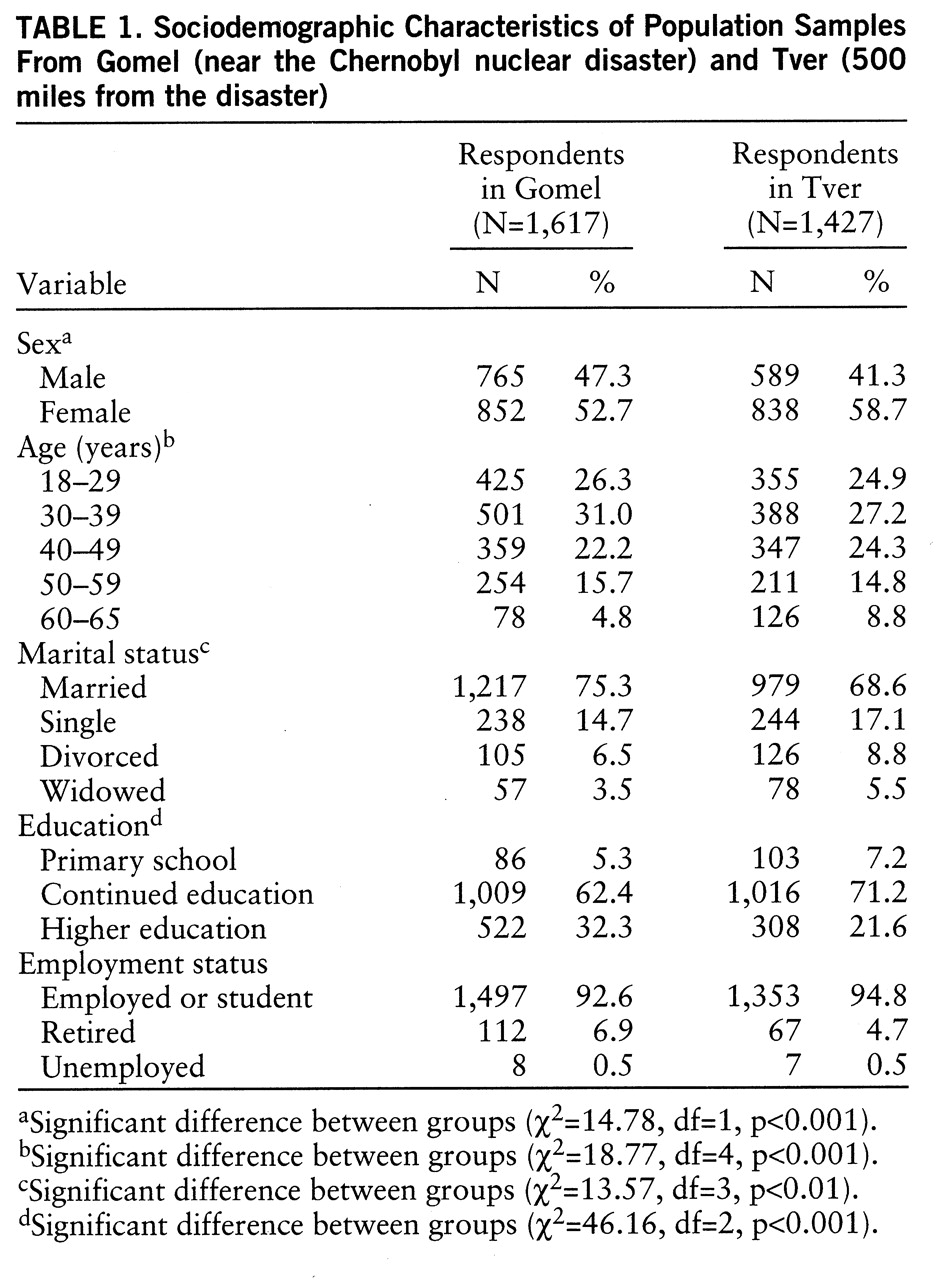

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the two phase 1 samples. The Tver sample contained significantly more women, more divorced and widowed persons, and fewer persons with higher education.

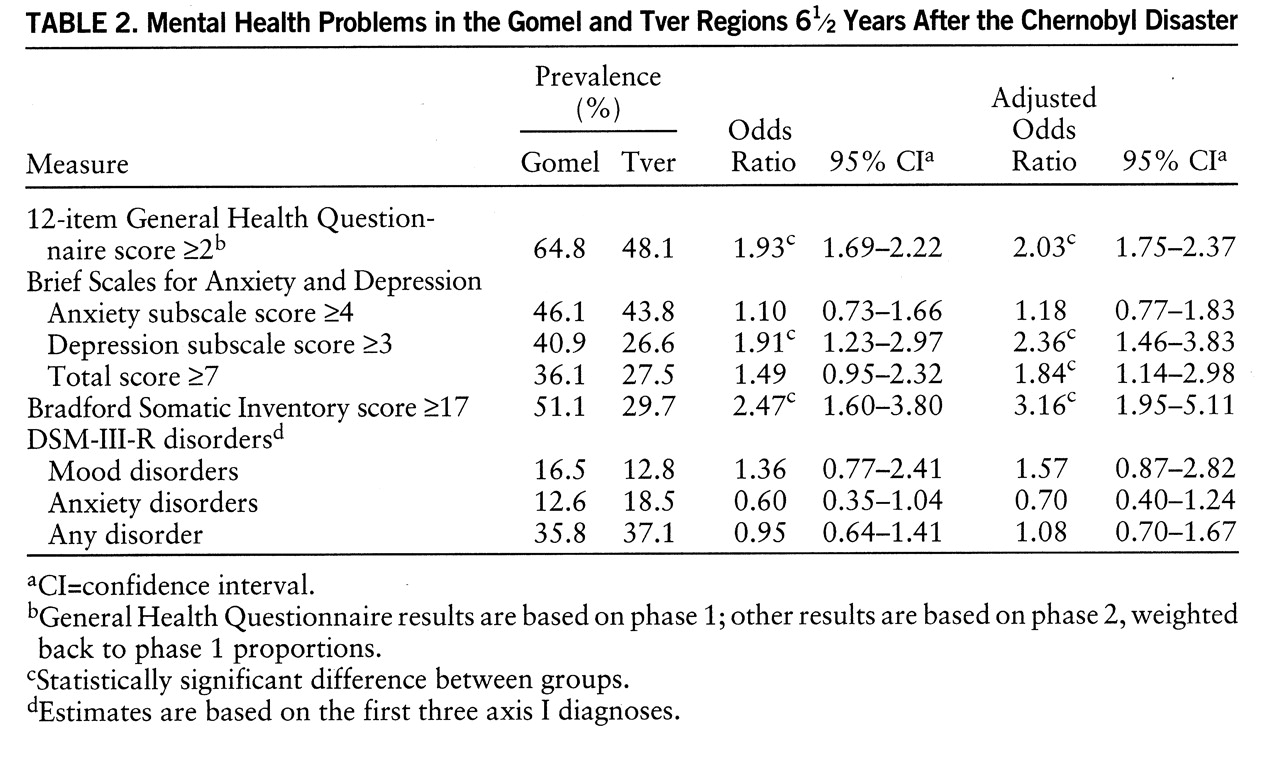

Table 2 presents the prevalence estimates and odds ratios for each of the outcome measures. Respondents from the Gomel region had significantly higher scores on all three psychiatric symptom scales, with the exception of the anxiety subscale of the Brief Scales for Anxiety and Depression. However, no statistically significant differences were found for the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Mood disorders were nonsignificantly more prevalent in the Gomel sample, mainly because of higher rates of depression not otherwise specified in Gomel (4.1% versus 1.0%). Anxiety disorders were more common in Tver, particularly general anxiety disorder (10.6% versus 4.1%). Posttraumatic stress disorder was seen more frequently in Gomel (2.4% versus 0.4%), but none of the respondents linked their complaints directly to the disaster. None of these differences was statistically significant.

Adding the interaction between being a mother and living in Gomel improved the fit of the logistic model significantly for the Brief Scales for Anxiety and Depression anxiety subscale score (log likelihood ratio=34.26, p<0.001) and total score (log likelihood ratio=13.44, p<0.05), for any DSM-III-R disorder (log likelihood ratio=79.84, p<0.05), and for DSM-III-R anxiety disorders (log likelihood ratio=15.44, p<0.001). These results indicate that for these outcomes, being a mother was a risk factor in Gomel but not in Tver.

DISCUSSION

= The aim of the study was to assess the long-term effects of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster on the mental health status of a severely affected population. The study shows high levels of psychopathology in the two regions studied, with significantly higher levels among the exposed population, especially among mothers with children under 18 years of age. The results corroborate earlier research on the mental health consequences of this disaster, which showed higher scores on the 12-item General Health Questionnaire among exposed women but not among men (

4). Our study now shows that higher levels of distress may be demonstrated among the entire adult population. At the level of clinically significant psychopathology, which has not been studied earlier, the differences appear to be limited to specific risk groups, especially mothers with young children.

A major limitation of our study was the sampling procedure, which excluded people who were institutionalized, on sick leave, or on maternity leave. This may have led to an underestimation of the prevalence of disorders (e.g., of psychotic disorders). However, it seems justified to compare these samples because of the standardized approach to sample selection and data collection in the two regions. Also, there were sociodemographic differences between the exposed and the unexposed groups. The somewhat higher odds ratios after adjustment for these variables suggests that these differences have minimized differences in mental health status between the two samples. Finally, selective migration from the disaster area may have attenuated differences in mental health between the two regions.

Despite these limitations, our findings clearly suggest a substantial impact of the Chernobyl disaster on mental health among the affected population as long as 6 years after the event. The study confirms the observations following the Three Mile Island nuclear incident in 1979 and suggests that nuclear disasters, with their long-term physical health implications, may be more likely to induce chronic psychopathology than other disasters. The effects appear to be limited mainly to subclinical distress. However, in view of the higher rates of clinical pathology observed among mothers with young children in the exposed region, one may speculate that psychiatric symptoms among these women are fostered by genuine concern about the health of their children, (e.g., about the risk of thyroid cancer). Further research in this area and public health programs to mitigate the mental health consequences among this risk group are needed.