Olfactory identification deficits in schizophrenia provide evidence for cerebral dysfunction, although the etiology of this abnormality remains unknown. As the brain regions most consistently found to be abnormal in schizophrenia overlap with areas crucial to olfactory processing, assessing olfactory function may provide important information regarding the integrity of the medial temporal, thalamic, and orbitofrontal regions. Examining olfactory identification in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia could further our attempts to delineate the potential genetic contribution to olfactory dysfunction.

Family studies may help define genetic contributions to olfactory dysfunction in schizophrenia (

1,

2). In a preliminary study (

1), psychotic family members had significantly lower scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (

3) than did unaffected family members. In addition, the mean score of the unaffected family members was low, suggesting that a predisposition to schizophrenia could be associated with olfactory dysfunction. Recently, Moberg et al. (

2) also demonstrated significantly lower smell identification scores for siblings of patients with schizophrenia than for healthy comparison subjects.

We expected that scores for olfactory identification ability would be lower in affected and unaffected members of monozygotic twin pairs discordant for schizophrenia than in a normal comparison group and that the unaffected twins would have olfactory identification scores intermediate between those of the affected twins and the comparison group.

METHOD

The feasibility of using a mail-out version of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test was assessed. Twelve patients who had previously been smell tested by our group were chosen at random from the existing computer database. The test was mailed to each patient with instructions. Seven returned the completed test. Using a paired t test, we found no difference between the scores obtained by self-administration (mean=36.6, SD=2.6) and technician administration (mean=37.3, SD=1.8) (t=0.5, df=6, n.s.). In addition, self-administration procedures have been validated by Doty et al. (

3).

The smell identification test was mailed to 20 pairs of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia, a subset of 66 pairs studied by Torrey et al. (

4). Only data from the 12 twin pairs of which both members returned the completed test were scored and analyzed. After all data were tabulated, a random match for each twin pair was established from the existing database of healthy comparison subjects. Twins were matched by sex and age (within 5 years). Family history of serious mental illness was obtained by questionnaire and by direct interview with the parents. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

RESULTS

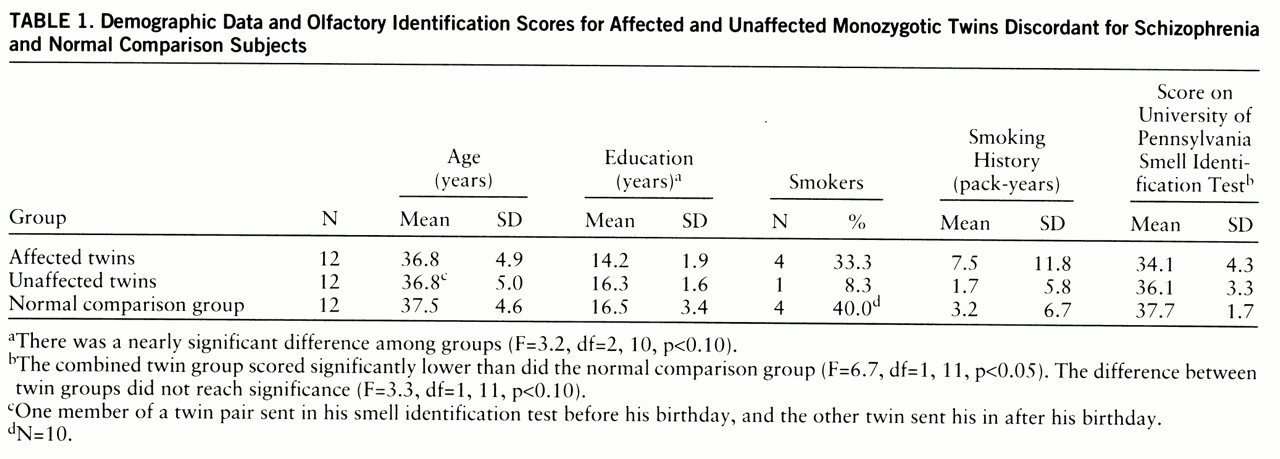

As shown in

table 1, no differences among the three groups in age or smoking history (in pack-years) were observed. There was a nonsignificant difference in highest level of education achieved.

Planned orthogonal contrasts were used to compare the raw scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. The combined affected and unaffected twins were compared to the normal comparison group. This combined group scored significantly lower than did the normal comparison group (

table 1). When the twins were compared to each other, the difference fell short of significance. When age and smoking status were used as covariates, the same pattern of significant results was obtained.

Using the cutoff scores established from standardization data (

3), we classified the subjects according to olfactory status. For women a score of less than 35 (out of 40) and for men a score of less than 34 would indicate microsmia. Microsmia was observed in 50% of the affected twins, 25% of the unaffected twins, and none of the normal comparison subjects.

A family history of serious mental illness was defined as having a first- or second-degree relative with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, major depression, alcoholism, or psychosis not otherwise specified, according to methods detailed by Torrey et al. (

4). The twin pairs with family histories were compared to those without such family histories. A one-tailed t test showed that the group with family histories scored significantly lower (mean=33.4, SD=4.4) than the group without family histories (mean=36.3, SD=3.1) (t=1.9, df=22, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The primary findings regarding the mean scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test were 1) a significantly lower score for the combined affected and unaffected twin groups than for the normal comparison group, but comparable scores for the two twin groups; and 2) a significantly lower score for the twin pairs with family histories of serious mental illness than for the twin pairs without such family histories.

The proportion of individuals who were microsmic differed among the three groups: one-half of the affected twins, one-quarter of the unaffected twins, and none of the normal comparison group were so classified. Smoking status was unlikely to have contributed to the observed microsmia as the normal comparison group had the highest proportion of smokers and the best performance on the smell identification test.

The results of the current study are consistent with findings from previous research. We and others (

5,

6) reported olfactory identification deficits in approximately 50% of medicated male patients with schizophrenia. Subsequent studies (

7) revealed that never-medicated first-episode patients with schizophrenia also had olfactory deficits. The brain regions implicated as being dysfunctional are the medial temporal, thalamic, and orbitofrontal regions (

6,

8).

For our study group, no statistically significant difference in olfactory identification between affected and unaffected twins was observed. This finding is consistent with that reported for siblings discordant for schizophrenia by Moberg et al. (

2), who found that individuals with schizophrenia and their siblings had worse scores on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test than did a comparison group. The mean score of the unaffected siblings fell midway between the scores of the affected probands and the normal comparison group, a pattern consistent with the current findings.

Similarly, Cannon et al. (

9) reported that deficits in neuropsychological function were observed in unaffected relatives of individuals with schizophrenia and that the performance was intermediate between results for the probands with schizophrenia and a normal comparison group. Drawing from the same cohort of twins that was used in the current study, Goldberg et al. (

10) showed that the affected twins had significantly worse performance on neuropsychological measures than did the unaffected twins but that there was no significant difference between the unaffected twins and normal comparison subjects. The unaffected twins' performance was midway between the values for the affected twins and the normal comparison group. Finally, in an unrelated study (

4), neurological testing of this same cohort of twins revealed, again, that the unaffected twins' scores were midway between those of the affected twins and the normal comparison group.

The interesting finding that individuals with family histories of serious mental illness had significantly worse olfactory identification ability than did persons without such family histories supports a role for genetic factors. Given the small number of subjects and the directional t test used, the possibility that this is a chance finding cannot be excluded.

Taken together, these results suggest that there is a genetic contribution to cerebral dysfunction as assessed by the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. More definitive prospective investigations are required to determine whether the presence of olfactory identification deficits is predictive of vulnerability to psychosis.