Interest in the role of potential serotonergic abnormalities in panic disorder has prompted clinical evaluation of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The SSRIs are generally well tolerated and have become popular treatments of panic disorder (

1–

3). Paroxetine (

4,

5) and fluvoxamine (

6–

8) have been shown to be effective in controlled trials of panic disorder, and fluoxetine (

9,

10) and sertraline (

11) have been effective in open trials.

METHOD

Study Design

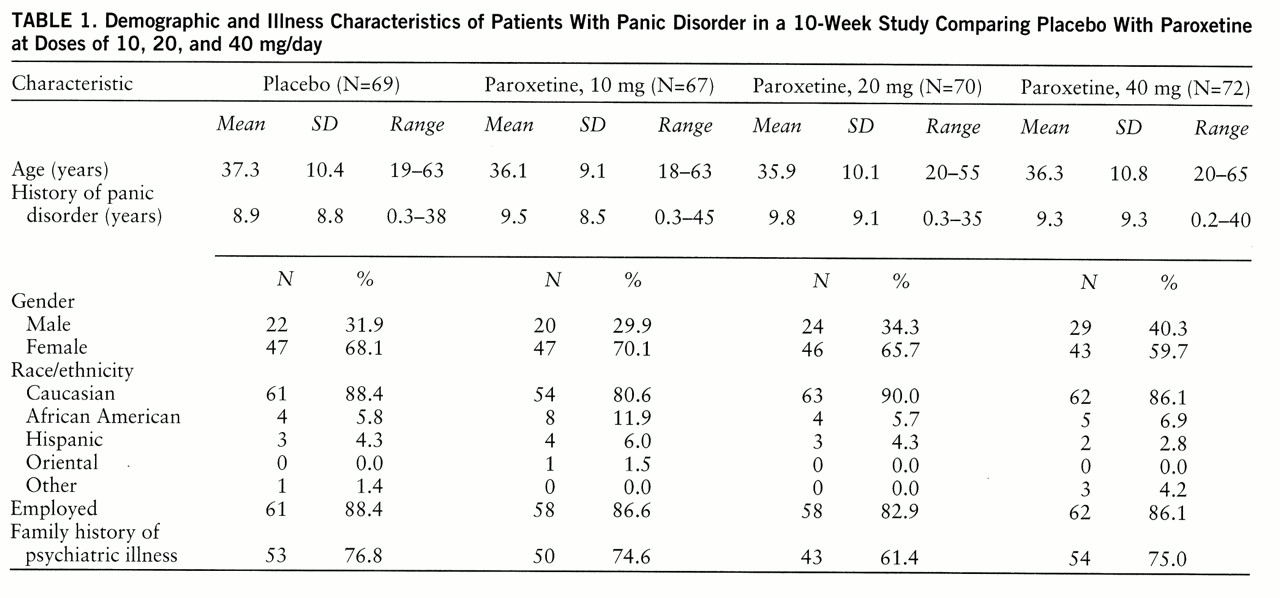

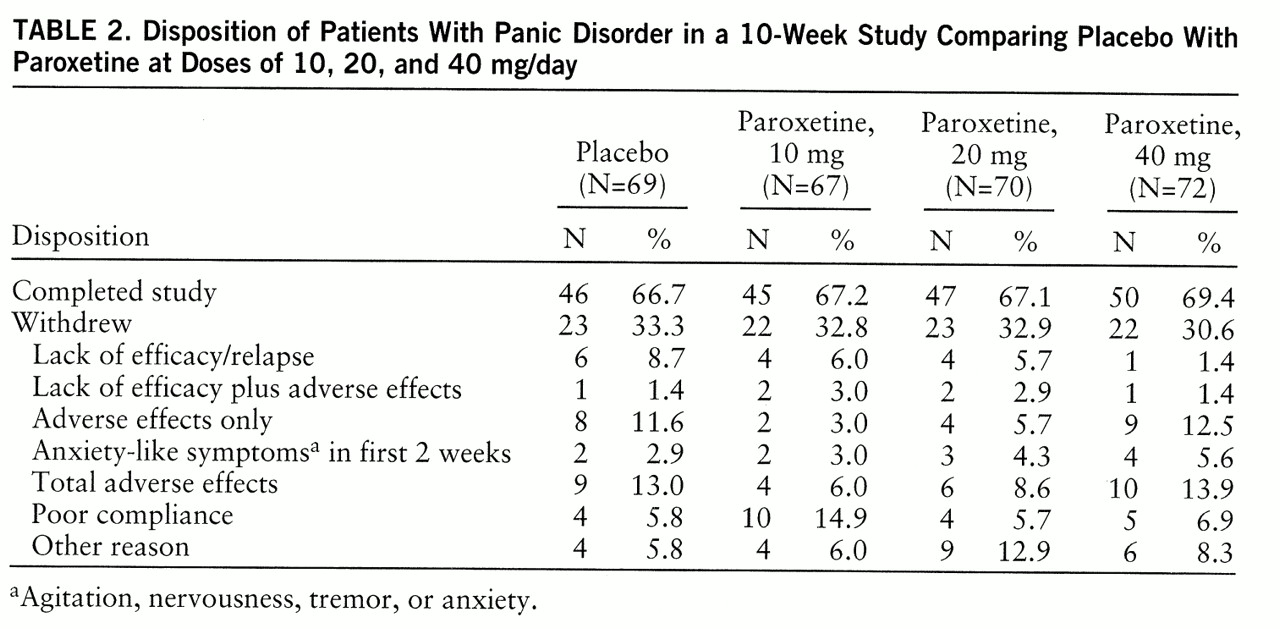

A double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled, parallel-design study was conducted in 20 centers in the United States and Canada. All patients received single-blind administration of placebo for 2 weeks. Patients meeting the entry criteria were then randomly assigned to receive placebo or 10, 20, or 40 mg/day of paroxetine for 10 weeks. The patients assigned to paroxetine began with 10 mg/day; the dose for the 20-mg and 40-mg groups was increased to 20 mg/day on day 8. The dose for the 40-mg group was increased to 40 mg/day on day 15. The patients were seen weekly during the first 4 weeks and biweekly thereafter.

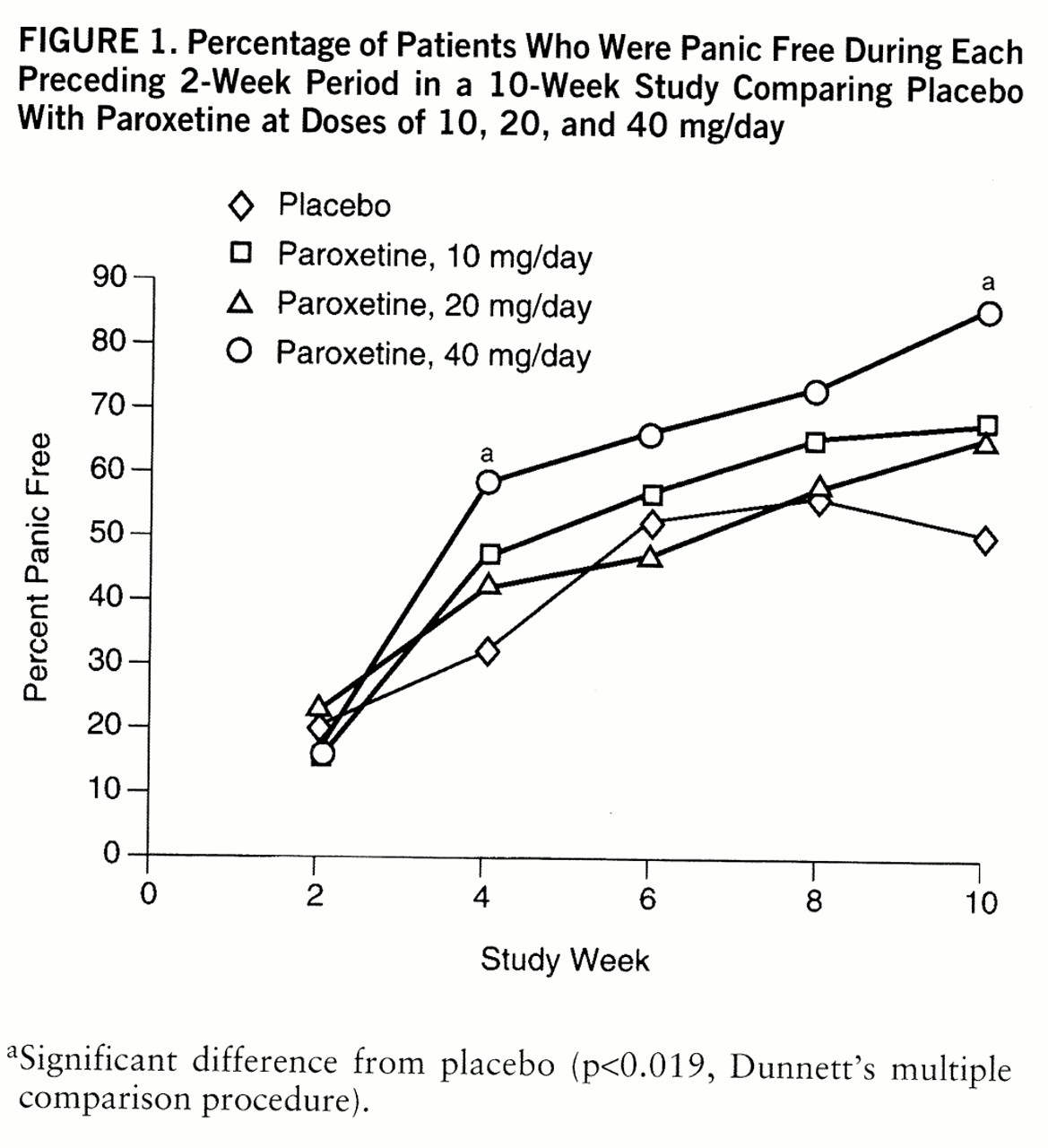

The number of subjects calculated to ensure 90% power to detect a 30% difference in response rates with a 30% attrition rate was 79 patients at each dose level. The comparisons of primary interest were the three doses of active drug versus placebo. Dunnett's procedure was used to maintain an overall alpha level of 0.05 for the three comparisons of primary interest. The rejection region for the pairwise comparison was p<0.019.

Patient Selection

Men and women 18 years of age or older who met the DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia were enrolled. In addition, eligible patients must have had at least two full panic attacks in the 2-week screening period. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all study centers, and the patients signed statements of informed consent.

A patient was excluded if he or she 1) was currently receiving psychotherapy; 2) had a current episode of primary major depression (i.e., preceding panic disorder and dominating the clinical presentation); 3) had another axis I disorder; 4) had a severe medical condition; 5) had substantial suicide risk; 6) had abused alcohol or other drugs recently; 7) was taking other psychotropic medication or oral anticoagulants concurrently; 8) had benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms during screening; 9) had shown intolerance to an SSRI in the past; 10) had major laboratory abnormalities; 11) had pregnancy, lactation, or childbearing potential without medically acceptable contraception; or 12) had taken medication that would affect the study results.

Measurements

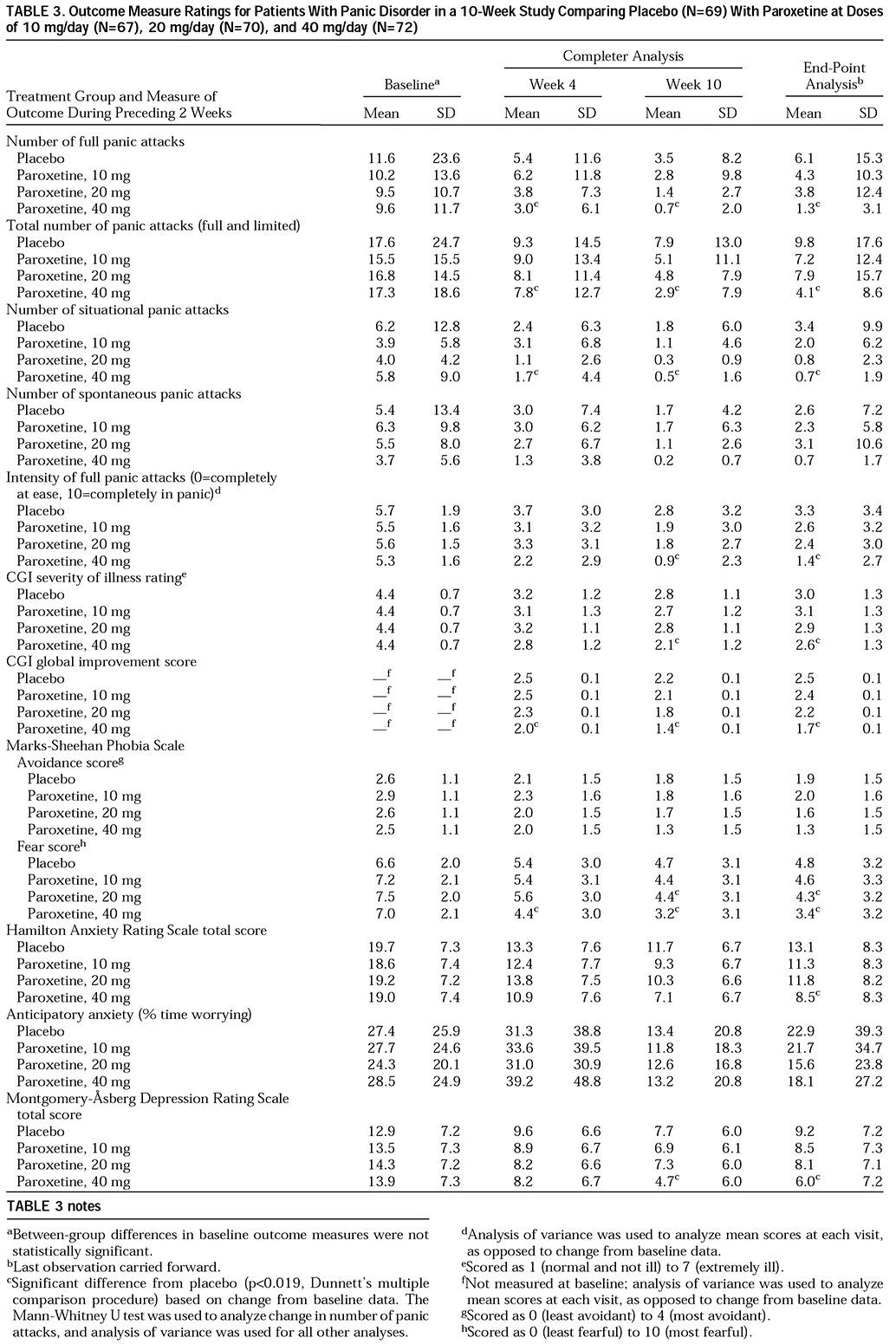

Four primary outcome measures were assessed for the 2-week period ending at week 10: 1) percentage of subjects free of panic attacks; 2) mean change from baseline in number of full panic attacks; 3) percentage of subjects with a 50% reduction from baseline in number of full panic attacks; and 4) Clinical Global Impression (CGI) score for severity of illness. The secondary outcome measures were mean number and intensity of full and limited-symptom panic attacks, number of unexpected and situational panic attacks, severity of anticipatory anxiety (percentage of time and intensity of worry about impending panic attacks), CGI global improvement score, and scores on the Marks-Sheehan Phobia Scale (

12), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (

13), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (

14), Sheehan Disability Scale (

15), and Social Adjustment Self-Report Questionnaire (

16).

Full therapeutic response was defined as the absence of full panic attacks during the 2-week period ending at week 10. Patients who were still experiencing full panic attacks but for whom the number of attacks was reduced at least 50% were considered partial responders.

The patients were asked nonleading questions about adverse effects at each visit. Routine laboratory testing (i.e., clinical chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis) and physical examinations were conducted at baseline and week 10. Serum and urine samples were obtained at baseline and weeks 4 and 10 for detection of surreptitious benzodiazepine use.

Data Analysis

The SAS statistical analysis package (

17) was used for all analyses. The percentage of patients achieving a dichotomous response (e.g., no full panic attacks) was analyzed by using logistic analysis of the categorical modeling procedure of the SAS system. The method produced chi-square tests for dose, site, and dose-by-site interaction and pairwise comparisons of each paroxetine dose versus placebo. Continuous data were analyzed by using parametric analysis of variance. Mean change from baseline in panic attack frequency was ranked and analyzed with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The statistical differences were two-tailed and considered to be significant at the 5% level. In the comparisons of paroxetine dose groups against placebo, Dunnett's multiple comparison procedure was used to maintain an overall alpha level of 0.05. This results in a critical region for pairwise tests of 0.019. Results for the intent-to-treat population were determined on the basis of the data sets for both completer analysis (observed cases) and end-point analysis (last observation carried forward).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that paroxetine at a dose of 40 mg/day is superior to placebo by week 4 across most outcome measures and is an effective and well-tolerated treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Paroxetine at a dose of 10 or 20 mg/day showed a tendency toward superiority over placebo, but these differences did not attain statistical significance, possibly owing to the large placebo response and the relatively small number of patients in each group. Patients in the 40-mg group had a mean of 9.6 panic attacks during the 2-week baseline period, but 86.0% were completely free of panic attacks at week 10. There were also significant differences between the 40-mg and placebo groups at week 10 in intensity of full panic attacks, CGI severity rating, and global improvement.

Patients with panic disorder often suffer from multiple anxiety and depressive symptoms (

18). We observed significant improvements in measures of phobic fear, anxiety, and depression with 40 mg/day of paroxetine.

Although the improvements in phobic avoidance were not statistically significant, 40 mg/day of paroxetine did result in significantly greater reductions in phobic fear. Because most effective antipanic agents do reduce agoraphobic avoidance, it is possible that paroxetine trials with greater power to detect differences would demonstrate significant improvement in phobic avoidance. Also, phobic avoidance usually improves later than do other symptoms, and perhaps a longer course of therapy would have resulted in greater reductions in avoidance. Also, higher doses may be required to reduce phobic avoidance, as has been observed with imipramine (

19) and alprazolam (

20). Further analysis of the clinical database of 218 paroxetine-treated panic patients indicates that more men than women met the treatment response criteria (72% versus 55%) (

21), and the incidence of agoraphobia is lower among men (

22). Clearly, the relationship between response in agoraphobic patients and treatment duration, dose, and gender requires further investigation.

We observed a substantial rate of response to placebo, which has become a problem in panic disorder studies, reaching as high as 50% (

23) and 61% (

24). The response to placebo in our study could be secondary to the frequent clinic visits, use of panic attack diaries, unintended cognitive restructuring, and escalating number of tablets provided during the first 3 weeks.

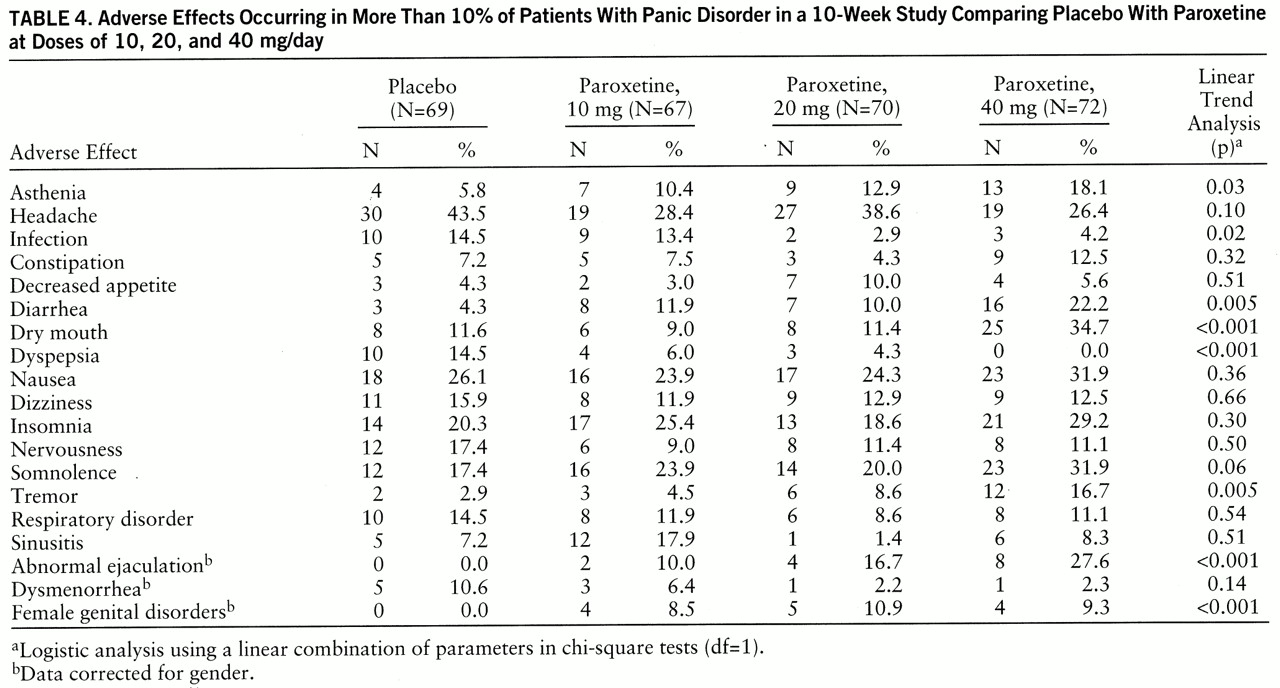

Paroxetine was well tolerated, and the adverse effects observed were those seen with the SSRIs: nausea, insomnia, somnolence, and sexual dysfunction (

25). Adverse effects that were more common as the paroxetine dose increased were dry mouth, tremor, diarrhea, abnormal ejaculation, and female genital disorders. Studies comparing the side effects of paroxetine and other available treatments for panic disorder would be important, but paroxetine appears to be safe and well tolerated.

This study was not designed to measure the early treatment-related jitteriness or anxiety-like symptoms that have been reported with other SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants (

9,

10,

26–

29). However, in the initial 2 weeks of treatment relatively little evidence of these activation-like symptoms was noted, and no patient withdrew from the study because of treatment-emergent jitteriness. Also, in the flexible-dose trial of paroxetine (

5), exacerbation of jitteriness was not observed.

The relatively few comparative studies of antipanic agents make meta-analyses of effect sizes across studies a rational means for comparing treatments. In such a meta-analysis, Boyer (

30) determined that SSRIs may be even more effective than tricyclic antidepressants or benzodiazepines for panic disorder.

The highest paroxetine dose used in this study, 40 mg/day, was the minimum dose demonstrated to be more effective than placebo, although some patients did respond to lower doses. Routine clinical practice should involve initial dosing at 10 mg/day, with gradual increases until a clinical response is observed. In this study, dose increases to 20 mg/day by week 2 and 40 mg/day by week 3 were well tolerated, and significant effects were observed among most outcome measures within 1 week after 40 mg/day was reached. Other studies with paroxetine (

5) have suggested that even higher doses (60 mg/day) may be useful.

Cognitive behavior therapy is also an effective treatment of panic disorder, and the findings from current studies of combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy are promising (

31).

Like treatment for major depression (

32), panic disorder treatment for some patients needs to be extended (

33) and may prevent or retard the return of panic symptoms. Indeed, preliminary analysis of a 12-week extension beyond this 10-week study (

34) demonstrated maintenance of the antipanic effect of paroxetine (N=116). The patients with sustained response during this 12-week maintenance period were then randomly assigned to placebo (N=37) or the same dose of paroxetine (N=43) for an additional 12 weeks. The patients receiving paroxetine were significantly less likely to experience a relapse (5%) than were those who were switched to placebo (30%) (χ

2=9.19, df=1, p=0.002).

Collectively, these data support the use of paroxetine for the short-term treatment of panic disorder and its long-term management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Paroxetine Panic Disorder Study Group consists of J. Ballenger and B. Lydiard (Charleston, S.C.); J. Carmen (Atlanta); G. Chouinard (Montreal); E. Coccaro (Philadelphia); L. Davis (Indianapolis); E. DuBoff (Denver); A. Feiger (Wheat Ridge, Colo.); J. Ferguson (Salt Lake City); S. Goldstein (New York); C. Houck (Birmingham, Ala.); J. Kreisle and M. Crismon (Austin, Tex.); J. Mattes (Princeton, N.J.); P. Morris (Toronto); D. Munjack (Beverly Hills, Calif.); C. Nemeroff and P. Ninan (Atlanta); P. Silverstone (Edmonton, Alta., Canada); S. Strawn and T. Rea (Bryan, Tex.); M. Tancer (Chapel Hill, N.C.); P. Tucker (Oklahoma City); and M. Van Ameringen (Hamilton, Ont., Canada).