Social phobia is an anxiety disorder characterized by the fear and/or avoidance of situations where an individual is subject to the scrutiny of others. Under such circumstances, the individual fears that she or he will say or do something foolish or embarrassing or will appear anxious to others (DSM-IV and ICD-10). Although social phobia used to be considered fairly uncommon, two epidemiologic surveys (

1–

3) have placed the 12-month prevalence of social phobia in the range of 7%–8%, a rate severalfold higher than that determined by earlier studies (

4,

5). Moreover, the recognition that social phobia is frequently associated with functional impairment (

6–

10) has brought it to attention as an important public health concern (

11,

12).

In concert with its recognition as a disorder worthy of serious research have come attempts to understand the etiology and pathophysiology of social phobia. One area of interest is in the possible heritability of social phobia (

13,

14). A large, population-based twin study of phobias in women demonstrated a heritable component to social phobia (

15). Two studies to date have examined familial characteristics of social phobia. The first (

16), using the family history method, found a significantly higher rate of social phobia among first-degree relatives of probands with social phobia (6.6%) than among first-degree relatives of control subjects (2.2%). The second (

17), a direct-interview family study, also found a significantly higher rate of social phobia in first-degree relatives of probands with social phobia (16%) than in first-degree relatives of control subjects (5%). In an extension of this study, the investigators were also able to show that social phobia “bred true” in the sense that rates of agoraphobia or simple phobia were not higher among the relatives of probands with social phobia (

18).

Researchers have surmised that social phobia may be a heterogeneous condition (

19–

25). In particular, it has been noted that whereas some patients with social phobia suffer exclusively from one or several performance fears (e.g., speaking in public or writing in front of others), others experience a broader array of social fears, including many interactional situations (e.g., meeting new people, attending parties, or talking to people in authority) (

19–

25). Although the field has yet to decide on a uniform nomenclature for classification of diagnostic subtypes in social phobia, there seems to be a consensus—reflected in the DSM-IV criteria—that there is a subgroup of individuals whose social fears span a broad range of social situations. Such individuals are referred to in the more recent literature as suffering from generalized social phobia.

With this background information available, we conducted a direct-interview family study of patients with generalized social phobia using a priori operational criteria for subtype designation. We hypothesized that we would find higher rates of generalized social phobia among relatives of probands with generalized social phobia. We also hypothesized that rates of avoidant personality disorder—thought by many to be the axis II equivalent of severe generalized social phobia (

25–

30)—would be higher in relatives of probands with generalized social phobia. Finally, we postulated that rates of avoidant personality disorder would be higher among relatives of probands with early-onset than among relatives of probands with late-onset phobia. Such a finding, conforming to the assumption that patients with early onset have more severe forms of disease (

31), would lend further credence to the conceptualization of avoidant personality disorder as a more severe form of generalized social phobia.

METHOD

Subjects

Thirty-three probands with generalized social phobia (age 18–65, English speaking) were recruited through our Anxiety Disorders Clinic. Subjects were assessed by using a version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version 1.0 (SCID-P) (

32), which we had modified to reflect changes in the anxiety disorder diagnoses in DSM-IV. All probands with social phobia met DSM-IV criteria for the generalized subtype; there were no exclusion criteria based on lifetime comorbidity. To be considered for the study, probands needed to have at least two living first-degree relatives whom we might potentially contact. Two subjects were unwilling to give permission to contact all of their first-degree relatives; they were dropped from the study. Of the 31 patients who gave permission to contact their relatives, we were ultimately able to directly interview only one first-degree relative of eight; these eight probands are not considered further in the analyses described below. (It should be noted, however, that none of the findings change if these eight probands are included in the analyses.) Therefore, we were left with 23 probands with generalized social phobia for whom we were able to interview at least two first-degree relatives.

We recruited 24 comparison subjects without social phobia by means of advertisements posted in hospitals and medical clinic waiting rooms. We attempted to match the groups with and without social phobia for age and gender. The only inclusion criteria were that the person not have a personal history of social phobia and that the person have at least two living first-degree relatives whom they would allow us to contact. There were no exclusion criteria (i.e., we did not use a “supernormal” group of comparison subjects [33, 34]). After preliminary screening by telephone, each potential comparison subject was interviewed with the same diagnostic instrument (modified SCID-P) used with the probands with generalized social phobia. Of 27 volunteers who contacted us about the study, three were excluded because they had personal histories of social phobia.

All first-degree relatives 16 years of age and older whom we were able to interview were included in the study.

All subjects gave their informed, written consent to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba.

Diagnostic Interviews

Interviews were conducted either in person (whenever this was feasible) or by telephone. The interviews with 54 (50.9%) of the 106 first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia were conducted in person, compared with 31 (41.9%) of the 74 first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (continuity-adjusted χ2=1.09, df=1, p=0.30). Mean interview duration was 69 minutes (SD=24, range=20–130) for the first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia, compared with 56 minutes (SD=21, range=20–100) for the first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (t=3.37, df=176, p<0.001).

Interviewers were selected on the basis of having had extensive previous experience with diagnostic interviewing in a research setting. Interviewers included two predoctoral-level clinical psychologists and one psychiatric research nurse (P.F., D.C., and S.L.). All interviewers attended workshops conducted by the principal investigator (M.B.S.) and a senior clinical psychologist (J.R.W.) on the use of the diagnostic instruments. Interviews with first-degree family members were conducted blind to information about the proband. All subjects were specifically instructed not to divulge any information about the proband to the interviewer, and “broken” blinds were noted.

The interview consisted of the mood (minus the dysthymia section), anxiety, and eating disorder sections of the SCID-P (

32), which we modified as follows: 1) The anxiety disorders module was modified to incorporate the changes that were anticipated for DSM-IV (

35). Because several options were available for some diagnoses, additional questions were added to enable us to go back and assign definitive diagnoses once the DSM-IV criteria were finalized. 2) The social phobia section was amplified with the aim of enabling us to assign subtypes on an a priori basis. To this end, we added probes for a wide range of social situations (appendix 1); many of these probes were borrowed from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version Modified for the Study of Anxiety Disorders (

36). Among our research group, the modified social phobia module has excellent interrater reliability for the diagnosis of DSM-IV social phobia (interrater reliability kappa=0.73, percent agreement=88%).

Social phobia was diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria. We operationally assigned subtype diagnoses of social phobia according to the following conventions: 1) The performance type could be either present or absent. If someone endorsed severe distress or any degree of avoidance with respect to at least one of the performance situations in appendix 1, then the performance type was considered present. 2) The interactional type could also be either present or absent. If someone endorsed one or two socially interactive situations in appendix 1, then they were considered to have the limited interactional type, whereas if they endorsed three or more they were considered to have the generalized interactional type. All subjects categorized in our study as having the generalized interactional type of phobia can be considered by definition as having the DSM-IV generalized subtype. Subjects with performance-only, limited-interactional-only, or performance-plus-limited-interactional types of phobia can be considered as having what is being increasingly referred to in the field as the nongeneralized subtype.

We conducted second interviews with 38 first-degree relatives of probands with social phobia 12 months after their initial interview. We found reliability (which, in this case, reflects an amalgam of test-retest and interrater reliability) to be very good (kappa=0.84, percent agreement=92%) for the generalized versus nongeneralized distinction.

A diagnostic module for avoidant personality disorder was included. This module was derived from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (

37) and conformed to DSM-III-R criteria. Follow-up interviews conducted with 36 subjects 12 months after their initial interview with the DSM-III-R avoidant personality disorder module demonstrated acceptable reliability (kappa=0.67, percent agreement=83%) for the avoidant personality disorder diagnosis. In the light of the changes in the criteria for avoidant personality disorder that have taken place between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, we can say with confidence only that our results are applicable to the former.

Diagnostic Standardization and Consensus Procedures

Diagnoses were established by consensus of the “blinded” members of the study team, which included the principal investigator (M.B.S.), three interviewers (S.L., P.F., and D.C), and two experienced clinician-researchers (M.J.C. and A.L.H). At a weekly diagnostic conference, interviews were presented in detail and diagnostic “benchmarks” were systematically noted as being met, not met, or indeterminate. When necessary to facilitate diagnostic clarity, subjects were reinterviewed either by the same or, in some cases, a second interviewer, and the new interview results were presented at a subsequent conference. When consensus could not be reached despite reinterview(s), the principal investigator served as the final arbiter.

As the study progressed, we established diagnostic conventions as became necessary. Whenever a new convention was established, all interviews that had previously been reviewed in conference were reexamined by the group to determine if any diagnostic reclassification was in order.

Data Analysis

Between-group differences in demographic variables were tested by using Student's t test or the chi-square test, as appropriate. Fisher's exact test or chi-square tests (continuity-adjusted for two-by-two tables) were used to contrast familial prevalence of disorders. To examine possible age or gender effects, the familial contrasts were repeated and hazards analysis (SAS PHGLM procedure) applied with these two variables as covariates. The pattern of results was not changed in this analysis, and so we report the results here without controlling for these factors.

The proportion of affected individuals (not including the proband) was computed for each family, and these values were compared for families of probands with generalized social phobia and for families of probands without social phobia by using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. When numerous ties were encountered in the ranked values, a permutation test of the Wilcoxon statistic was also performed by sampling from the possible random assignments of probands to families

(38, p. 189). Relative risk for generalized social phobia among first-degree relatives of probands in the two groups was determined as simply the ratio of proportions of affected relatives. However, familial clustering would tend to make standard relative risk confidence intervals (obtained by pooling across families)

(39, p. 182) too narrow; 95% confidence intervals, therefore, were obtained by first estimating the relative risk that any member of a family was affected (

40) and then adjusting for the average number of affected relatives per affected family. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical tests were two-tailed and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics and Comorbidity of the Probands

There were no significant differences between probands with generalized social phobia and probands without social phobia in either gender or age distribution. Six (26.1%) of the 23 probands with generalized social phobia and 10 (41.7%) of the 24 probands without social phobia were women (continuity-adjusted χ2=0.67, df=1, p=0.41). The mean age of the probands with generalized social phobia was 36.7 years (SD=12.2, median=35, range=18–62), compared with 32.9 years (SD=10.8, median=32, range=19–60) for the probands without social phobia (t=1.13, df=45, p=0.26).

Seventeen (73.9%) of the 23 probands with generalized social phobia had avoidant personality disorder, but none of the probands without social phobia received that diagnosis. Lifetime comorbidity among the probands with generalized social phobia was as follows: two had a history of panic disorder, four simple phobia, five generalized anxiety disorder, and seven major depression. Lifetime comorbidity among the probands without social phobia was as follows: one had a history of panic disorder, one simple phobia, two generalized anxiety disorder, and three major depression.

Characteristics of the First-Degree Relatives

There were no significant differences between groups in the proportion of relatives interviewed. We were able to directly interview 106 (80.9%) of 131 living first-degree relatives of the probands with generalized social phobia and 74 (78.7%) of 94 living first-degree relatives of the probands without social phobia (continuity-adjusted χ2=0.06, df=1, p=0.81). There were also no significant differences between the probands with generalized social phobia and the probands without social phobia in the proportion of relatives interviewed according to gender. Seventy-one (67.0%) of the 106 interviewed first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia were female, compared with 40 (54.1%) of the 74 interviewed first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (continuity-adjusted χ2=2.2, df=1, p=0.14). Among the living first-degree relatives who were not interviewed, 15 (60.0%) of 25 relatives of probands with generalized social phobia were women, compared with seven (35.0%) of 20 relatives of probands without social phobia (continuity-adjusted χ2=1.87, df=1, p=0.17).

There were no significant differences between groups in family size (χ2=7.62, df=3, p=0.07). Specifically, among the 23 families of probands with generalized social phobia, two family members were interviewed in two families, three were interviewed in nine families, four were interviewed in four families, and five or more were interviewed in eight families. Among the 24 families of probands without social phobia, two family members were interviewed in nine families, three were interviewed in 10 families, four were interviewed in one family, and five or more were interviewed in four families.

The mean age of the first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia was 42.2 years (SD=16.5), compared with 39.3 years (SD=15.6) for the first-degree relatives of the probands without social phobia (t=1.18, df=177, p=0.24).

Aggregation of Social Phobia Subtypes in Families

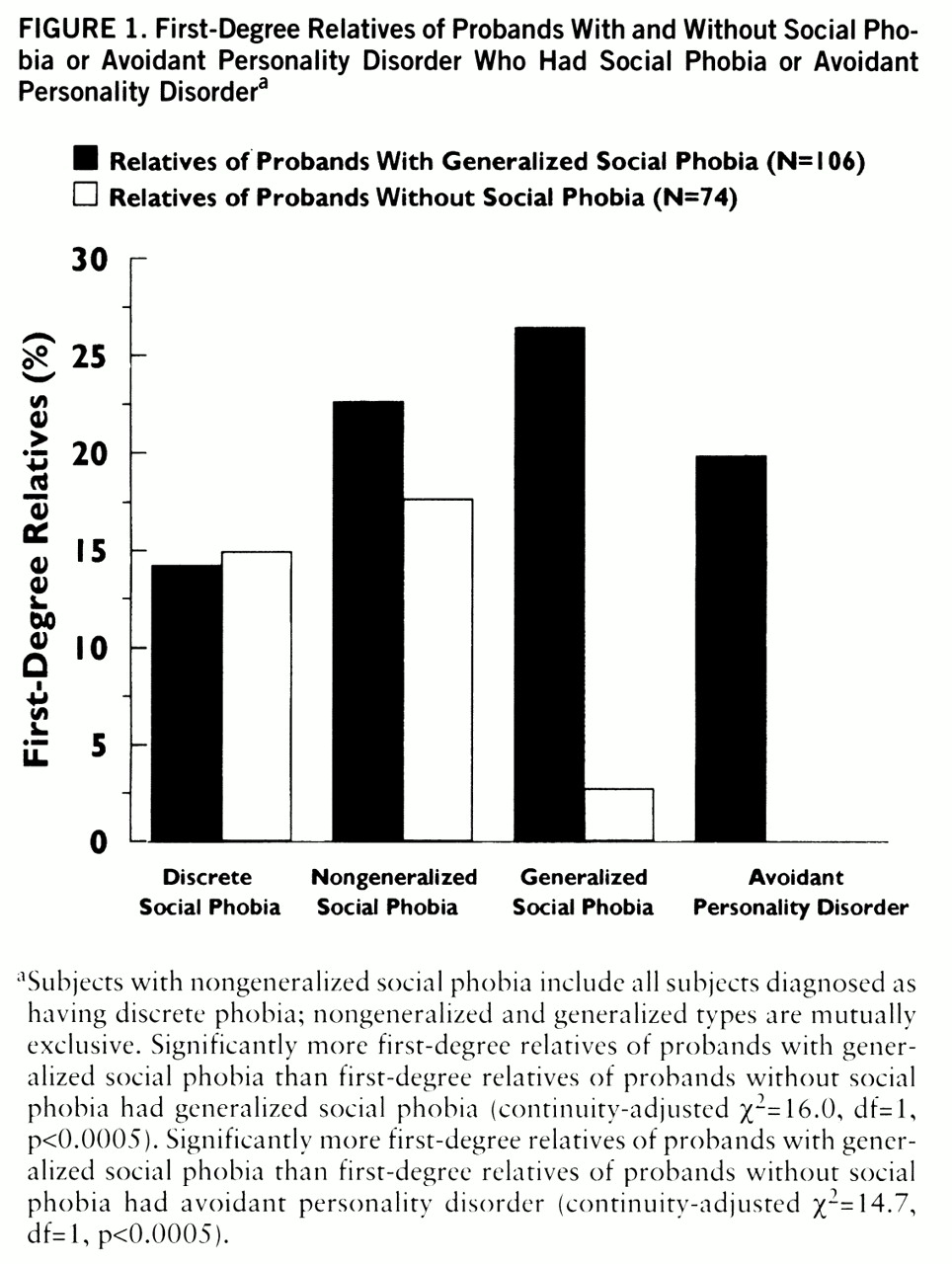

The rates of particular subtypes of social phobia subtypes in families are shown in

figure 1. The performance-only (or discrete) subtype was present in 15 (14.2%) of 106 first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia, compared with 11 (14.9%) of 74 first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (continuity-adjusted χ

2=0.01, df=1, p=0.94).

We next considered in aggregate the performance-only or limited-interactional subtype—a grouping synonymous with the nongeneralized subtype. This was found in 24 (22.6%) of 106 first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia, compared with 13 (17.6%) of 74 first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (continuity-adjusted χ2=0.41, df=1, p=0.52).

The generalized subtype of social phobia was present in 28 (26.4%) of 106 first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia, compared with two (2.7%) of 74 first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (relative risk=9.7, 95% confidence interval=2.51–38.1). The proportion of affected individuals per family (excluding the proband) was 0.23 (SD=0.21) for the families of probands with generalized social phobia, compared with 0.4 (SD=0.14) for the families of probands without social phobia (z=3.63, p=0.0003). (Because of the presence of ties in the ranked values, a permutation test of the Wilcoxon statistic was also performed by sampling from the possible random assignments of probands to families [38], yielding a similar value of p=0.0002 in 20,000 permutation samples.)

Aggregation of Avoidant Personality Disorder in Families

Avoidant personality disorder was present in 21 (19.8%) of 106 first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia, compared with none of 74 first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia (relative risk not meaningful because no family members of probands without social phobia were affected); each of these individuals also had generalized social phobia. The proportion of affected individuals with avoidant personality disorder per family was significantly higher for families of probands with generalized social phobia (mean=0.17, SD=0.18) than for families of probands without social phobia, who had none (z=4.15, p=0.0001; a permutation test of 20,000 samples similarly gave p=0.0001). The likelihood of a relative having avoidant personality disorder was not associated with the presence of avoidant personality disorder in the probands with generalized social phobia: four (26.7%) of 15 first-degree relatives of six probands with generalized social phobia but not avoidant personality disorder had avoidant personality disorder, compared with 18 (30.5%) of 59 first-degree relatives of 17 probands with generalized social phobia plus avoidant personality disorder (p=1.00, Fisher's exact test).

Age at Onset and Family History

There was a nonsignificant trend for age at onset to be lower in the probands with a positive family history of generalized social phobia (mean=11.1 years, SD=4.5) than in the probands who had no family history of generalized social phobia (mean=15.6 years, SD=8.5) (t=1.71, df=21, p<0.11). There was no difference, however, in the rates of avoidant personality disorder (or generalized social phobia) among relatives of probands with early-onset (prior to age 13) versus late-onset (age 13 or later) generalized social phobia (p>0.10).

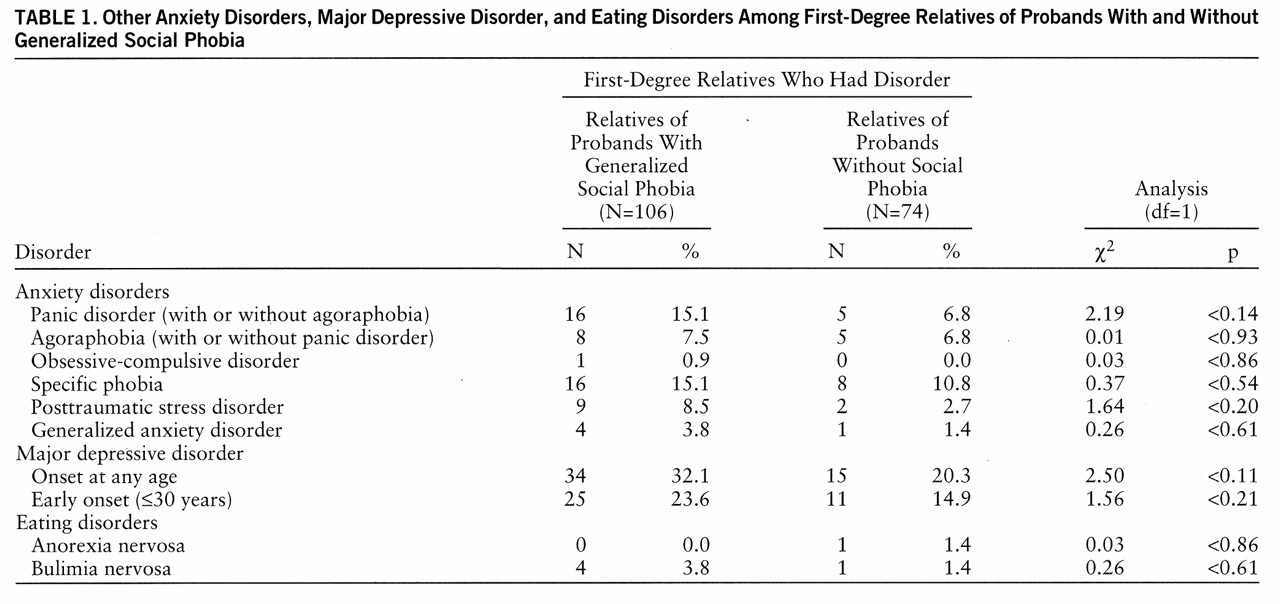

Other Anxiety Disorders, Major Depressive Disorder, and Eating Disorders

Lifetime rates of other anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder (including the subcategory of early-onset major depression [i.e., age at onset ≤30 years]) (

41,

42) are shown in

table 1. Although there were no significant differences in rates of any of these disorders among the first-degree relatives of the two proband groups, rates of panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depression were elevated among relatives of probands with generalized social phobia. Given the relatively small number of subjects and our resultant inability to control for rates of proband comorbidity for each of these disorders, these data should be considered of exploratory value only and will require confirmation in future studies.

DISCUSSION

In this direct-interview family study, we found that the rate of generalized social phobia—but not discrete or nongeneralized social phobia—was approximately 10 times higher (26.4% versus 2.7%) among the first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia probands than among the first-degree relatives of probands without social phobia. These observations confirm the finding from an earlier study of a higher rate of social phobia among relatives of probands with generalized social phobia (

26) and extend these findings by indicating that it is the generalized subtype that is uniquely higher.

The fact that the generalized form of social phobia “bred true” in this study, in the sense that other forms of social phobia were equally common among relatives of probands with generalized social phobia and relatives of probands without social phobia, suggests that generalized social phobia may be distinct from less pervasive forms of social phobia (

11,

19,

26). If the generalized versus nongeneralized distinction were purely one of severity, then one would have expected to see higher rates not only of severe social phobia (i.e., the generalized type) among first-degree relatives of probands with generalized social phobia but also of less severe forms of social phobia (i.e., the nongeneralized type) as well. The absence of such a tendency in our data is further supportive of this subtype distinction on a familial basis. Still, our data are suggestive but not confirmatory in this regard because we lacked the contrasting control necessary to confirm a causal distinction between the generalized and nongeneralized subtypes. To do so one would need to examine the morbid risks for generalized and nongeneralized social phobia among the relatives of probands with nongeneralized social phobia.

We found that avoidant personality disorder was confined to the relatives of probands with generalized social phobia. In all cases (both in probands and in relatives), avoidant personality disorder occurred only when generalized social phobia was also present. This observation, rather than reflecting true comorbidity per se, most likely is due to the substantially overlapping criteria sets for the two disorders (

27–

30). In our opinion, the observation that avoidant personality disorder is strongly familial must be interpreted in this context, i.e., that it is for all intents and purposes just another way of saying that generalized social phobia is strongly familial. On the other hand, our failure to find higher rates of avoidant personality disorder in relatives of probands with early-onset phobia than in relatives of probands with late-onset phobia does not fully support a continuum model for these disorders (i.e., that avoidant personality disorder is a more severe form of generalized social phobia). In order to fully understand the nature of the familial relatedness between avoidant personality disorder and generalized social phobia, it would be necessary to conduct a family study where four groups of probands (and their relatives) could be examined: subjects with avoidant personality disorder and generalized social phobia; subjects with avoidant personality disorder but no generalized social phobia (if such people exist); subjects with generalized social phobia and no avoidant personality disorder; and subjects without either generalized social phobia or avoidant personality disorder.

Although we assessed rates of other anxiety and mood disorders in the relatives in this study, our findings are inconclusive with respect to determining their familial relatedness to social phobia. The reason for this is that the number of subjects in our study was simply too small for this purpose. In order to examine the familial relatedness of some of the conditions that are frequently comorbid with social phobia in clinical samples (e.g., patients with major depression, panic disorder, and/or agoraphobia) (19–25, 43, 44), it will be necessary to include sufficient probands with and without each of these comorbid disorders to permit these informative contrasts to be made (

45,

46).

One common comorbid condition that, regrettably, we did not evaluate in this study is alcoholism. There lingers considerable controversy about the familial relationship between alcohol abuse and dependency and social phobia and, indeed, about whether individuals with social phobia are at greater risk for alcoholism (

47–

50). We chose not to invest our limited resources in the thorough assessment of substance use disorders in this study, but we recognize this as a shortcoming of the present study and hope to be able to address this important issue in future studies.

Another potential shortcoming of this study might be our use of telephone interviews whenever a face-to-face interview was not possible. Although we did not find systematic differences in diagnosis on the basis of the mode of interview, the possibility that the results would have been different if all subjects had been interviewed in person cannot be excluded. On the other hand, our use of telephone interviews when necessary permitted us to interview an extraordinarily high proportion of living relatives, and we would submit that this advantage far outweighed any potential disadvantages of telephone interviews. Furthermore, there is strong support in the literature (

51,

52) for the utility of telephone interviews and their comparability to face-to-face interviews for the diagnosis of lifetime psychiatric disorders. In our previous research (

53), we have used telephone interviews to advantage in the assessment of social phobia and social phobic symptoms.

In interpreting our findings, it must be remembered that with a family study we are unable to discern to what extent the familial nature of generalized social phobia is truly “heritable,” as opposed to what extent it is the product of a particular constellation of family-specific experiential factors. For example, there is reason to hypothesize that particular parenting styles might create or at least perpetuate social phobia in children (

54,

55). Testing this hypothesis, however, must take into consideration the probability that parental genetic makeup influences parenting behavior (

56). If future studies are able to determine that there is a heritable component to social phobia—and this would be strongly suspected to be the case, given the extant data—then it will be prudent to ask the question, “What exactly is inherited?” One plausible candidate is the temperament known as “behavioral inhibition” (

57,

58).

Behavioral inhibition refers to the tendency among some young children to respond to the unfamiliar with wariness and avoidance (

57,

58). Rates of behavioral inhibition are higher among children of parents with panic disorder and agoraphobia, and behavioral inhibition itself may represent a childhood precursor to social phobia (

59–

61). To test this hypothesis, it will be important to include “high-risk” probands—children of parents with generalized social phobia—in future studies in which behavioral inhibition is assessed. It will also be important to follow the children prospectively to determine to what extent behavioral inhibition represents a temperamental precursor (or “risk factor”) for the eventual crystallization of generalized social phobia.

In summary, we conclude that generalized social phobia appears to be a familial form of the disorder. More work is required to determine whether other forms of social phobia (e.g., discrete or nongeneralized subtypes) are also familial and, moreover, whether these forms segregate distinctly. Once the phenotypic spectrum of transmission is determined, it will be possible to use a variety of research approaches (

62) to elucidate genetic factors that might be important for the expression of social phobia as a disorder and, perhaps, shyness as a trait.

APPENDIX 1. Social Phobic Situations Covered by the Family Study Interview

Performance Situations

Public speaking

Performing in public (other than public speaking)

Eating in front of others

Writing in front of others

Urinating in a public bathroom

Taking a test

Entering a room where people are already seated

Using a pay phone (with someone standing nearby)

Trying on clothing in a store

Playing charades

Speaking up at a meeting

Interactional Situations

Speaking on the telephone (unobserved)

Interacting with strangers (e.g., asking directions)

Attending social gatherings (e.g., house parties, weddings)

Interacting with the opposite sex (e.g., asking someone out for a date)

Dealing with an authority figure (e.g., teacher, boss)

Returning items to a store

Making eye contact

Expressing disagreement/disapproval to someone

Ordering food in a restaurant

Dealing with a salesperson

Conversing in a group (e.g., at a party, in informal situations at work)