Over the years, the issue of the comorbidity of eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has been discussed often. Many authors have agreed that the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders among patients with OCD is 11%–13% (

1–

4). In addition, other studies have described a high lifetime prevalence of OCD (15%–33%) among patients with anorexia or bulimia nervosa (

5–

7) and a current prevalence of 3%–37% (

5,

7–

10). The reason for the comorbidity of the two disorders is unclear. Comparative studies have revealed marked similarities as well as differences in personality and psychopathological features between patients with eating disorders and those with OCD (

11–

18). Thus, it has been hypothesized that anorexia and bulimia nervosa belong to the family of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders (

19,

20).

In the 1960s, it was assumed that anankastic personality traits and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in anorectic patients indicated a poorer prognosis (

21). More recently, some authors have suggested that patients with comorbidity might respond differently to various types of treatment (

7,

22). To date, it is still unclear which factors are crucial for the long-term outcome of eating disorders (

23–

25). Therefore, controlled studies on this issue have been recommended in order to isolate variables that may be critical for prognosis (

24,

26).

Our objective in the present study was to investigate the question of whether concomitant OCD influences the treatment outcome of patients with anorexia or bulimia nervosa.

RESULTS

Retrospective analyses of the pretreatment data revealed no significant difference between the follow-up group (N=75) and the dropout group (N=18) for the following variables: the proportion of anorexia or bulimia nervosa diagnoses (χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.94), the prevalence of concomitant OCD (χ2=1.50, df=1, p=0.22), and the pretreatment Eating Disorder Inventory total score (t=0.03, df=89, p=0.98).

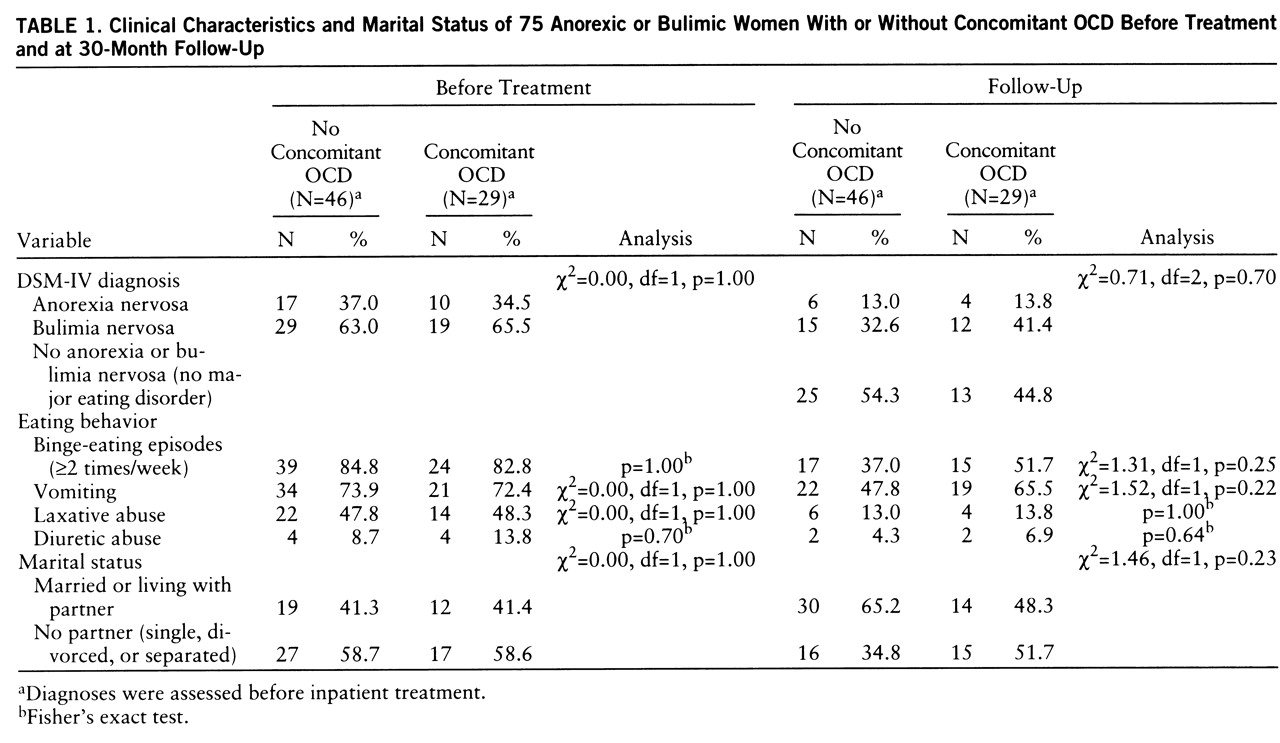

At follow-up 30 months later, 38 women in the follow-up group (51%) no longer fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Ten women (13%) and 27 women (36%) still met the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, respectively. We found no significant differences in eating disorder diagnosis, eating behavior, and marital status between the groups with and without concomitant OCD (

table 1).

Thirty-eight subjects (51%) reported that they had continued outpatient psychotherapy after discharge. There was no correlation between the presence or absence of concomitant OCD and outpatient continuation of psychotherapy (χ2=0.15, df=1, p=0.70).

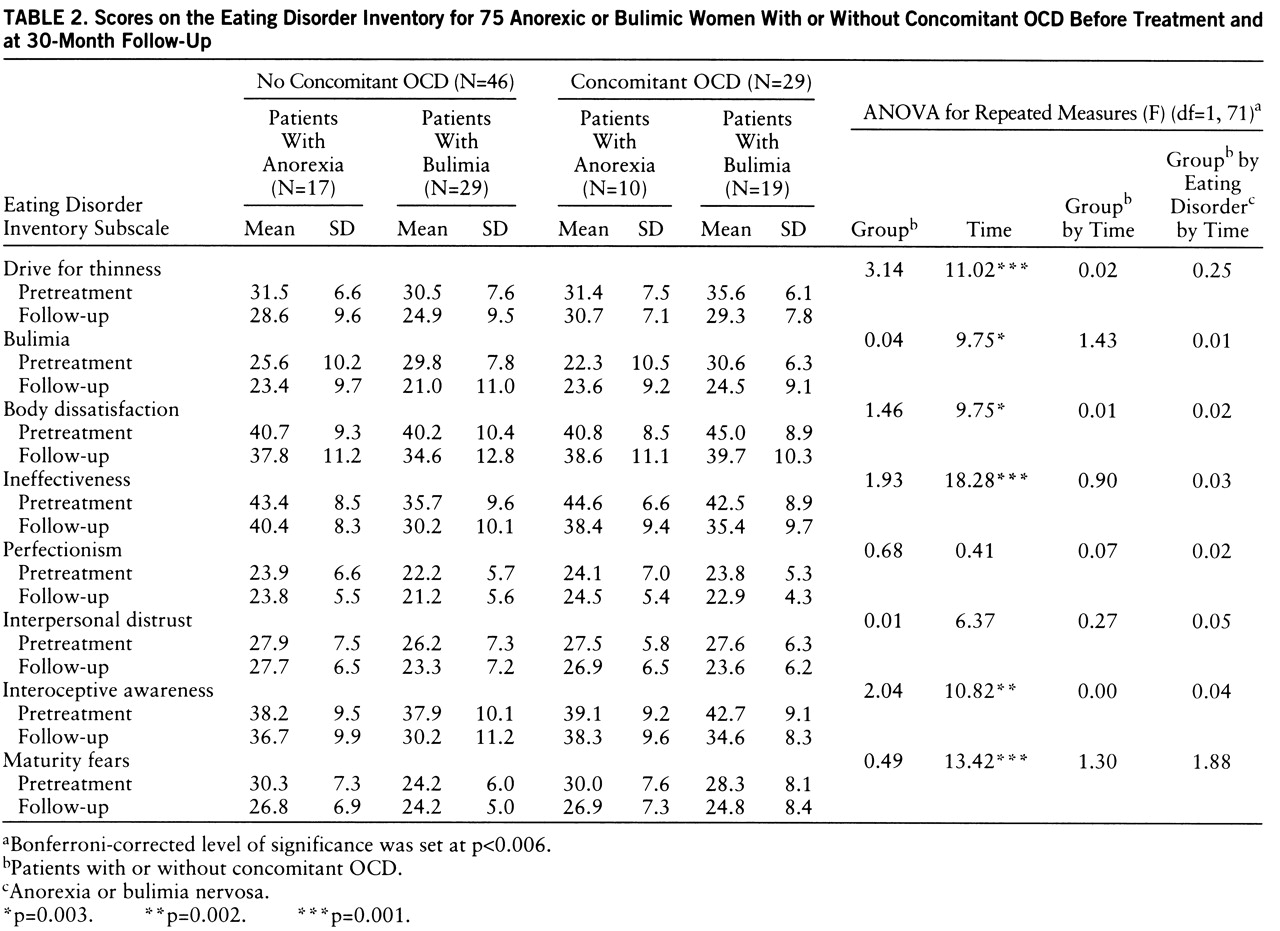

Table 2 presents mean Eating Disorder Inventory scores at each assessment for anorectic and bulimic patients with and without concomitant OCD. ANOVAs revealed significant time effects on six of the eight subscales, which indicates a general improvement of the total group during the follow-up period. Furthermore, no significant group effects or group-by-time interactions could be identified.

At follow-up, 32 women (43%) showed clinically significant change on at least one of the eight Eating Disorder Inventory subscales, and there was no statistically significant difference between the group with concomitant OCD and the group without comorbidity: 10 of the 32 improved women (31%) had concomitant OCD and the remaining 22 (69%) did not (χ2=0.81, df=1, p=0.37).

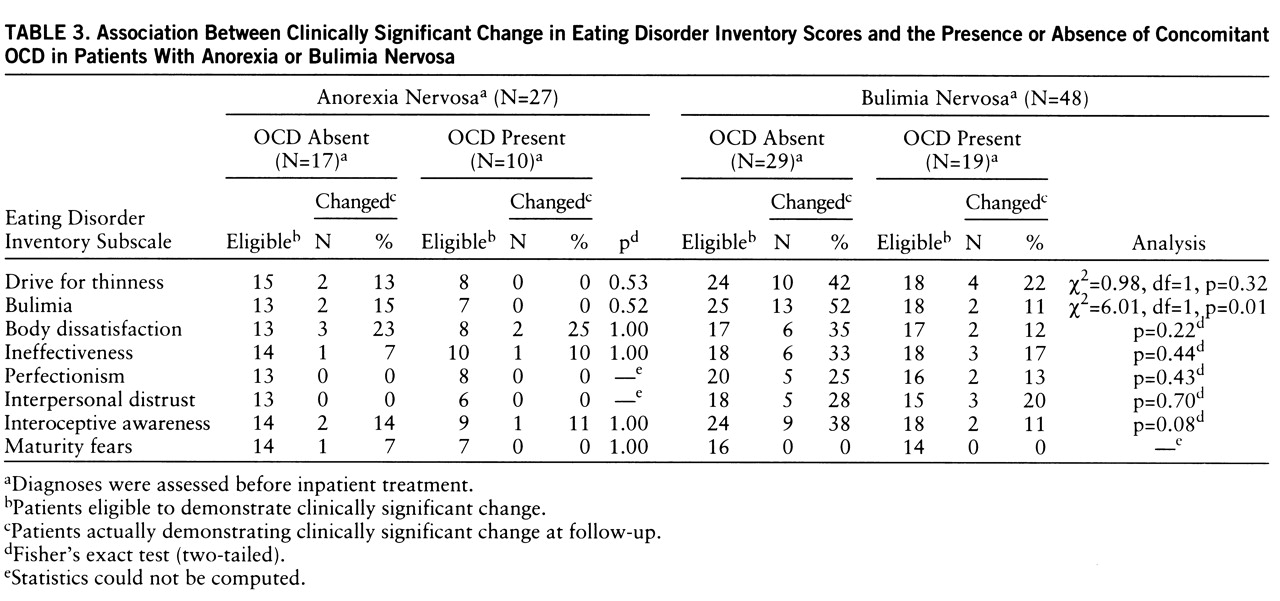

The number of patients with anorexia or bulimia nervosa who showed clinically significant change at follow-up is indicated for each Eating Disorder Inventory subscale in

table 3. Patients with bulimia nervosa without concomitant OCD showed a somewhat higher percentage of clinically significant change on seven of the eight Eating Disorder Inventory subscales. This result might suggest a somewhat poorer prognosis for patients with bulimia nervosa and concomitant OCD. However, the difference between bulimic patients with and without concomitant OCD did not reach statistical significance. All in all, the anorexia nervosa group showed a poorer outcome than the bulimia nervosa group, and the correlation between clinically significant change and the presence or absence of concomitant OCD was only slight and not statistically significant.

The obsessive-compulsive behavior in each group, i.e., anorectic or bulimic patients with and without concomitant OCD, developed differently during the follow-up period. The median total score on the Hamburg Obsession-Compulsion Inventory (sum of the six subscales) decreased significantly in the group with concomitant OCD from 27 before treatment to 21 at follow-up (p=0.001, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test), while the median total score for the patients without concomitant OCD was unchanged at 19. At follow-up, the comparison of both groups revealed no significant difference in the Hamburg Obsession-Compulsion Inventory—Short Form median score (p=0.40, Mann-Whitney U test) or difference score (p=0.09, Mann-Whitney U test).

The Hamburg Obsession-Compulsion Inventory—Short Form difference score in women who showed a clinically significant change on at least one of the eight Eating Disorder Inventory subscales was higher than the difference score of those women without any clinically significant change (p=0.003, Mann-Whitney U test). This higher difference indicates a greater reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptoms in those women whose eating disorder had improved.

DISCUSSION

We examined patients with anorexia or bulimia nervosa during inpatient treatment and again 30 months after discharge to investigate whether concomitant OCD influences the prognosis of the eating disorder. Follow-up assessment revealed somewhat more clinically significant change in the group without concomitant OCD, but this trend did not reach statistical significance. In summary, the results suggest that concomitant OCD does not indicate a significantly poorer prognosis for patients with anorexia or bulimia nervosa.

To date, we are not aware of any other studies that have investigated this issue in a prospective design. Fahy and Russell (

39) have reported interesting results about outcome and prognostic variables in bulimia nervosa. They used a retrospective analysis to compare pretreatment clinical features of patients with good outcome and those with poor outcome 1 year after cognitive behavior therapy and found no difference in Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory scores between the groups. Although the method that they used was quite different from ours, the results of both studies are largely consistent.

The women who participated in our study were treated with psychodynamic therapy. Our results, therefore, indicate long-term outcome figures following this type of treatment alone. The question remains whether a different type of therapy might lead to different results. Cognitive therapy and treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been recommended for patients with eating disorders as well as for those with OCD (

40–

42). Thus, it would be interesting to investigate whether patients with eating disorders and concomitant OCD might be more responsive to these types of therapy than patients without comorbidity. Without reaching statistical significance, our results suggest that concomitant OCD predicts a somewhat poorer prognosis for patients with anorexia nervosa and particularly for patients with bulimia nervosa. A similar study that used a different type of therapy might demonstrate a clearer result.

At follow-up, the Hamburg Obsession-Compulsion Inventory scores of both patient groups were surprisingly lower than one would expect to find in patients with OCD. The decrease in obsessive-compulsive symptoms was closely correlated to the clinical improvement reflected by the scores on the Eating Disorder Inventory scales. The patients whose eating disorders were most improved at follow-up also showed the highest reduction of obsessions and compulsions. Our results are consistent with the findings of Channon and deSilva (

43), who found in anorectic patients a significant reduction in Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory scores after treatment and weight restoration.

To date, two issues remain unclear (

19,

44). First, what is the reason for the association between OCD and eating disorders? Is there a connecting link or a common cause underlying both disorders? If so, is it biological or psychological in nature? Second, are obsessive-compulsive symptoms antecedents or consequences of eating disorders? We agree with Holden (

15) that obsessions and compulsions may be provoked or accentuated during the course of an eating disorder, possibly as a consequence of psychological stress or biological factors, e.g., as a result of starvation. Our data demonstrated that an improvement in the eating disorder was correlated with a reduction in obsessive-compulsive symptoms. We hypothesize that the decrease in obsessive-compulsive behavior was a consequence of this improvement. Swift et al. (

45,

46) have made similar observations about the relationship between depression and bulimia nervosa. Further research on this issue, including longitudinal follow-up studies and detailed psychopathological and biological assessment, might provide new insight into the relationship between eating disorders and OCD.