Long axon connections among different regions in the nervous system are established early in development. These connections mediate essential information transfer among specialized cerebral centers to form integrated functional systems. For example, the retina of the eye connects with multiple visual centers in the brain, including the lateral geniculate (visual) nucleus of the thalamus. The lateral geniculate nucleus is connected to the occipital (visual) cortex. The retina-lateral geniculate-visual cortex pathway mediates certain visual functions. Axons that connect retinal ganglion cells to the brain develop in three distinct phases: 1) elongation, 2) collateralization, and 3) arborization. First, unbranched axon trunks extend from the bodies of retinal ganglion cells and traverse all of their potential targets without forming connections with them. Second, the axon trunks sprout “collateral” branches in multiple targets simultaneously. Many of these collaterals are “exuberant” in the sense that they are formed within visual and nonvisual brain nuclei from which they later withdraw. Third, some of the collaterals of each axon grow and branch repeatedly to form mature terminal arbors, whereas other collaterals are eliminated. These processes are controlled by multiple mechanisms, including chemical signals from the target neurons and the electrical activity of neurons. Perturbations of these modulatory influences can alter the mature pattern of neuronal connections.

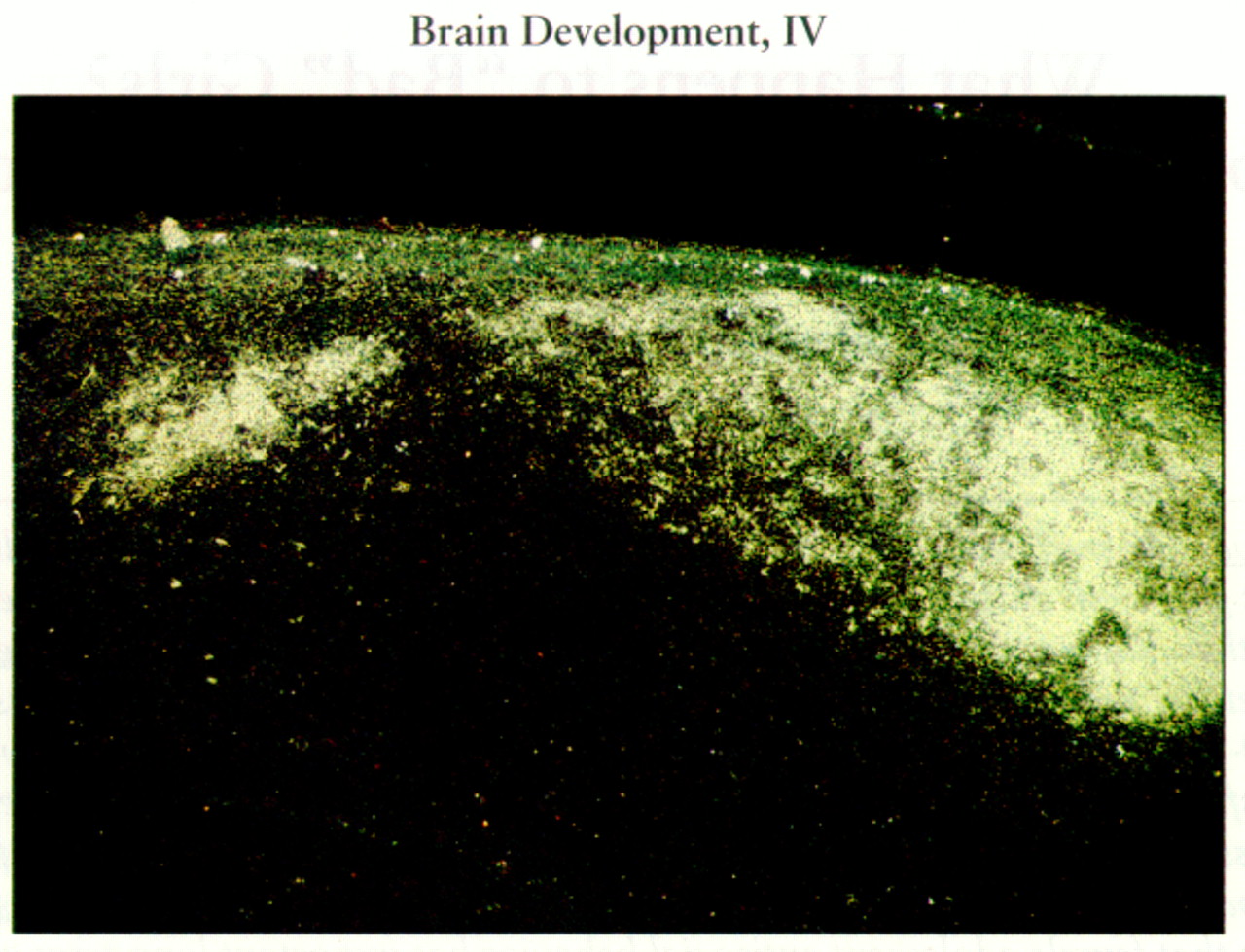

The figure illustrates an extreme example of the structural and functional plasticity of the developing nervous system: retinal ganglion cell axons within the auditory nucleus of the thalamus (the medial geniculate body). Newborn hamsters were subjected to ablation of the lateral geniculate nucleus and visual cortex, as well as transection of the ascending auditory pathways that project to the medial geniculate body. (At birth retinal ganglion cell axons are beginning to make collaterals within their cerebral targets.) As a consequence of this manipulation, the axons of retinal ganglion cells sprout collaterals within the medial geniculate nucleus, which subsequently develop mature terminal arbors and synaptic connections. By using a similar strategy, retinal ganglion cell axons can also be directed to the somatosensory nucleus of the thalamus.

The surgically induced retinal projections to the auditory and somatosensory systems form an orderly representation of the visual world, as do normal retinal projections to the lateral geniculate nucleus. The novel connections are also functional. In surgically manipulated hamsters, neurophysiological recordings in the auditory and somatosensory cortices (which receive input from the respective thalamic nuclei) demonstrate that single neurons in those cortical areas respond to visual stimulation in the same ways as visual cortical neurons in normal animals. Furthermore, hamsters with novel retinal projections to the auditory system can use their auditory thalamus and cortex to perform visual behavioral tasks that are mediated by the visual thalamus and cortex in normal animals. Mechanisms similar to those acting in this experimental situation may result in a cascade of structural and functional changes in cerebral circuitry in developmental diseases. More limited neural plasticity can also occur following insults to the mature nervous system, with both salutary and deleterious consequences. The novel, surgically induced retinal projections are also being explored as a paradigm for surgical repair of the central nervous system.