Depression in later life is a major public health problem, often associated with prominent medical comorbidity (

1). Medical illnesses may contribute to depressive pathogenesis through direct effects on brain function or through psychological or psychosocial mechanisms. As an example of the latter, personality trait neuroticism by definition implies emotional vulnerability to stress; persons high in neuroticism might experience greater depressive symptoms in the face of increased medical burden (

2). While recent studies have examined the role of categorically defined personality disorders in later-life depression (

3,

4), only one examined dimensional personality traits (

5). No study has examined whether neuroticism moderates the association between medical illness and later-life depression.

We tested the hypotheses that 1) medical illness burden is associated with depression independent of neu~roticism and 2) there is an interaction such that subjects with higher neuroticism have a greater association of medical burden and depression. Our subjects were drawn from primary care sites because of the public health importance of understanding psychopathology and medical comorbidity in these settings.

METHOD

Subjects were recruited from private internal medicine offices or a family medicine clinic (described previously in reference 6 and also by Lyness et al. in an unpublished manuscript). All patients ages 60 years and over who gave formal verbal informed consent (procedures approved by the University of Rochester's Research Subjects Review Board) were eligible to participate. Stratified sampling on a self-report depression inventory was used to oversample patients with significant depressive symptoms, but patients across the full range of screening scores were included. In-depth assessments were conducted by trained master's level raters using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (

7) and the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

8). Neuroticism was assessed by the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (

9), a 60-item self-report questionnaire with demonstrated reliability and long-term stability. Its neuroticism factor, similar to other scales used in published depression studies, includes items assessing proneness to affects and ideation found in depression. Medical illness severity was assessed by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (

10), on the basis of physician-investigator (J.M.L.) review of each patient's primary care chart and all other available records. Other measures included the self-reported Geriatric Depression Scale (

11) and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale from DSM-III-R.

We used multiple logistic and linear regression techniques to examine the independent associations of medical illness burden and neuroticism with the dependent measures of depressive diagnosis (current or any history of major depression), depressive symptoms (Hamilton depression scale and Geriatric Depression Scale), and psychiatric function (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale), while controlling for age, gender, and education. To determine whether any association of medical illness with the Hamilton depression scale was due merely to physical symptoms, the Hamilton depression scale also was divided into two 12-item subscales assessing affective/psychological and somatic/neurovegetative symptoms, respectively. To test for interactions of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale and neuroticism, polynomial interaction terms were created by computing powers and cross-products. Both second- (e.g., x2, xy, y2) and third- (e.g., x3, x2y, xy2, y3) order terms were included (second alone and then both combined) as independent variables in separate regression analyses; only the second-order cross-product interaction term is reported because the third-order terms did not yield additional information. Logarithmic or squared transformations of data were used when necessary to stabilize the variances. One-tailed p values were used because of the a priori directional hypotheses.

RESULTS

A total of 196 subjects completed all study measures. Their mean age was 70.4 years (SD=7.1, range=60–89); 119 (61%) were women. The mean Hamilton depression scale score was 8.1 (SD=6.4, range=0–32), and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score was 6.0 (SD=2.9, range=0–16). Twenty-eight subjects did not complete the NEO-Five Factor Inventory or other study measures. They did not differ statistically from the study subjects in age, gender distribution, Hamilton depression scale score, or Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score, although they had less education (mean=11.6 years, SD=3.1, versus mean=13.3, SD=2.8) (t=2.63, df=30.7, p=0.01).

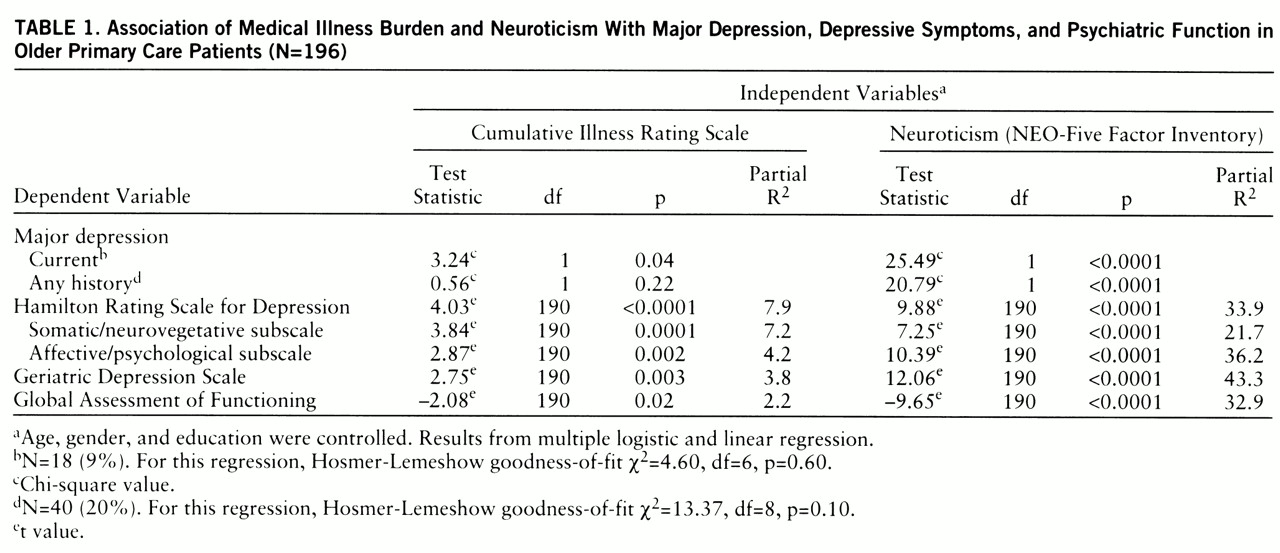

Table 1 shows the results from the first set of regression analyses. Both the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale and neuroticism were significantly and independently associated with all outcome variables, except the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale was not associated with history of major depression.

Turning to the regressions that examined interactions, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-neuroticism cross-product interaction term was significantly independently associated with current major depression (χ2=3.75, df=1, p=0.03) and with history of major depression (χ2=5.67, df=1, p=0.008), such that higher Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score and greater neuroticism were associated with a greater likelihood of depressive disorder. (The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit chi-square values for these two regressions were as follows: χ2=3.39, df=3, p=0.34, and χ2=8.15, df=8, p=0.42, respectively, indicating a good fit.) However, the interaction term was not significantly associated with the other outcome variables.

DISCUSSION

Our first hypothesis was confirmed: medical illness burden was independently associated with current major depression, depressive symptoms, and psychiatric function. Our hypothesis that neuroticism moderated the association of physical illness with depression received partial support, because the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-neuroticism interaction term was independently associated with major depression, but not with the Hamilton depression scale or the Geriatric Depression Scale.

Neuroticism's independent association with the outcome variables supports the need to further examine personality traits in the pathogenesis of depressive disorders in later life (

2). However, the measurement of neuroticism is potentially confounded by depression itself (

12). The state-trait aspects of this confound may be addressed to some extent by longitudinal studies or informant reports, but the conceptual overlap between trait neuroticism and depressive symptoms is more vexing. Specific avenues that may prove fruitful include examination of whether neuroticism's role as a moderator between medical illness and depression is influenced by factors such as medical disability, pain, or self-health perception and examination of neuroticism's role as a moderator in specific medically or psychiatrically defined patient subgroups.