The relatively few studies conducted to date on the prevalence of panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and social phobia in patients with affective psychoses have reported prevalence rates ranging from 4.9% to 42.6%

(1–

5). Psychotic patients with such comorbidities may have more severe symptoms, longer hospitalizations, lower rate of recovery at discharge, and worse response to somatic treatment than those without comorbidity

(1–

3,

6,

7).

There is some evidence that more than one comorbid diagnosis may occur in these subjects. For example, Strakowsky et al.

(1) found that 22% of a cohort of manic patients at first hospitalization had multiple comorbidity. The rate of comorbid disorders reached 37.7% when patients with unipolar depression and schizophrenia were included

(2). However, these studies did not specify whether such multiple associations were entirely accounted for by anxiety diagnoses.

The present study aimed to explore patterns and clinical correlates of multiple association of panic disorder, OCD, and social phobia in a cohort of consecutively hospitalized patients with affective psychoses.

METHOD

The method of this study has been described in detail elsewhere

(7). For the purpose of this study, 77 consecutively hospitalized psychotic patients were selected on the basis of the following criteria: 1) age over 16 years, 2) presence of psychotic symptoms (i.e., formal thought disorders, delusions, hallucinations, grossly disorganized behavior), and 3) provision of written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were psychotic symptoms secondary to acute intoxication, withdrawal from psychotropic substances, or severe medical conditions. The inclusion diagnosis of affective psychosis was made by a senior psychiatrist not directly involved in the study. Subjects were interviewed to confirm inclusion diagnosis and to assess axis I comorbidity the week before their discharge; the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P)

(8) was used. For the assessment of comorbidity, the SCID-P hierarchy was maintained for the psychotic disorder diagnosis; therefore, patients who met the criteria for schizophrenia or delusional disorder were excluded from the analyses. After previous training in the use of the instrument, three resident physicians interviewed patients with the SCID-P. To complete the SCID-P, information was obtained from any source available in addition to the patient interview, including medical records, first-degree relatives, and treating clinicians. Syndromes clearly secondary to the principal psychotic illness were not rated as comorbid disorders by interviewers.

Psychopathology was assessed with the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(9), the SCL-90

(10), and the Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

(11). Insight was evaluated by the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorders

(12).

Interrater reliability for the SCID-P, BPRS, SANS, and Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorders was assessed in a small study (N=8) on the basis of joint records for both principal and comorbid diagnoses. Good reliability established from joint ratings was obtained for both principal and comorbid diagnoses (kappa=0.87 and 0.82, respectively).

The chi-square test was adopted to analyze categorical variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The likelihood of the association of panic disorder with each of the other two anxiety disorders was analyzed by means of two logistic regression models with, respectively, social phobia and OCD as dependent variables and age, sex, and mood disorder diagnosis as independent variables.

RESULTS

Of the 77 patients, 48 had a bipolar I disorder, 18 had unipolar depression, and 11 had schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. The mean age was 33.5 years (SD=10.3), 57.1% were women, and 48.1% were in their first hospitalization; there were no significant differences among the three diagnostic subgroups. The level of awareness of illness was similar in the three diagnostic subgroups. Overall, frequencies of panic disorder, OCD, and social phobia were 24.7% (N=19), 23.4% (N=18), and 18.2% (N=14), respectively. Only social phobia was more frequent in unipolar (38.9%) than in bipolar (10.4%) patients (χ2=7.13, df=1, p<0.03).

A single comorbid anxiety disorder was found in 33.8% (N=26) of the cohort; 14.3% (N=11) had two or three anxiety diagnoses. The logistic regression analysis showed that panic disorder was significantly associated with OCD (odds ratio=3.68, 95% CI=1.05–12.81); this association was stronger in women than in men (odds ratio=4.33, 95% CI=1.02–18.25). Panic disorder was also significantly associated with social phobia (odds ratio=5.37, 95% CI=1.23–23.27); no cases of comorbid social phobia plus OCD were found without panic disorder as well. Patients with social phobia were younger than those without social phobia (mean=28.0 years, SD=5.9, versus mean=34.8, SD=10.7) (t=2.28, df=75, p<0.03).

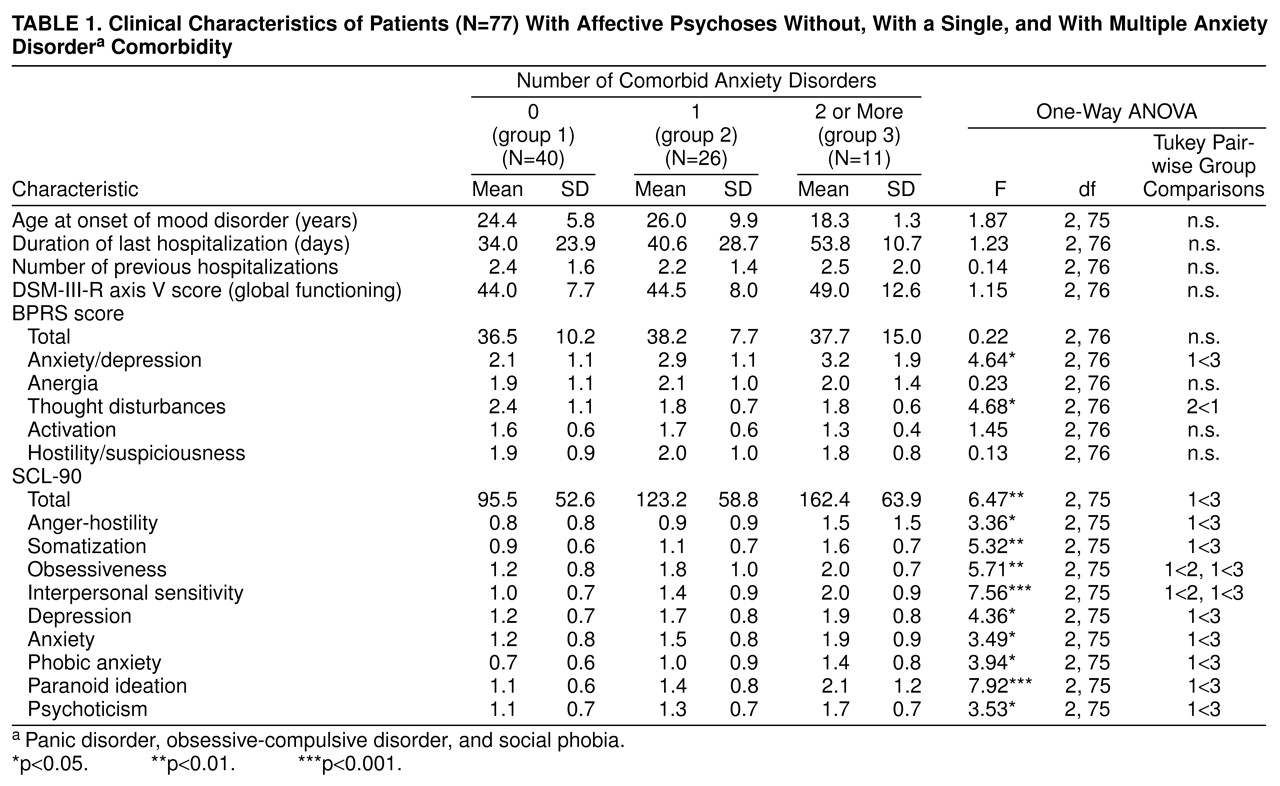

Patients with multiple anxiety comorbidity had significantly higher scores than those without anxiety comorbidity on all SCL-90 subscales, except for obsessiveness and interpersonal sensitivity, and on the BPRS anxiety/depression subscale. Conversely, patients without anxiety comorbidity had higher scores on the BPRS thought disorders subscale than patients with a single anxiety diagnosis (

table 1).

On the SANS scale, patients with social phobia had higher scores on alogia (t=–2.62, df=75, p<0.01) and anhedonia/asociality (t=–1.76, df=75, p<0.08) than patients without social phobia.

As for substance abuse, we found a significantly higher frequency of stimulant abuse among patients with multiple anxiety comorbidity (18.2%) than among those with a single anxiety disorder (0%) and those without comorbidity (2.5%) (χ2=7.26, df=2, p<0.03).

DISCUSSION

Two limitations of this preliminary study must be acknowledged. Because of the small group size, analyses of comorbidity in bipolar and schizoaffective subjects were carried out without discriminating between those with prevalent manic episodes and those with predominantly depressive episodes, which may differ from each other on several phenomenological characteristics. Moreover, we were not able to separately analyze generalized and specific social phobia.

Despite these limitations, our data indicate that panic disorder, OCD, and social phobia are common, occurring either singly or in mutual association in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic features. The three anxiety disorders appeared to be more common in the present cohort than in the general population. In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study

(13), lifetime prevalences were 1.6% for panic disorder, 2.5% for OCD, and 2.8% for social phobia. The rates of panic disorder and OCD in our bipolar patients were higher than those found in the ECA database (respectively, 27.1% versus 20.8% and 22.2% versus 21%)

(4,

5). On the contrary, the frequency of social phobia among our bipolar subjects was much lower than that found in bipolar I subjects in the National Comorbidity Survey (10.4% versus 47.2%)

(14).

We did not find subjects with OCD plus social phobia without panic disorder. This finding is difficult to interpret. Further studies in larger populations of subjects should clarify whether this finding is due to chance or whether panic disorder may increase the likelihood of having additional anxiety disorders.

Our patients with multiple anxiety disorders were likely to have more severe psychopathology and to abuse stimulants more frequently than patients without comorbidity. These results support the importance of detecting specific multiple associations of anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with severe mood spectrum disorders. If these associations are unrecognized, they may negatively affect the phenomenology of mood disorder or may induce the patient to turn to substances for self-medication, to the detriment of an adequate treatment

(3,

6,

15).