Social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder) is characterized by the fear (and consequent avoidance in many cases) of situations where an individual fears humiliation or embarrassment when under the scrutiny of others. Whereas many persons in the community fear performance situations such as public speaking, only a minority of these persons suffer from enough attendant disability or distress to qualify for a diagnosis of social phobia

(1). Furthermore, although social phobia has classically been described as a fear of performance situations (e.g., public speaking, eating in public, writing in public), it is now recognized that many persons with social phobia—particularly those seen in clinical settings—suffer from a more pervasive form of the disorder that results in their fear and avoidance of a multitude of performance and interactional situations (e.g., dating, talking to strangers, speaking to authority figures). This more debilitating form of the disorder, often referred to as “generalized social phobia,” is a serious, often underdiagnosed condition that carries with it a tremendous burden of disability

(2). Overall, epidemiologic reports place the point prevalence of social phobia in the range of 7%–8%

(3,

4), a rate that far exceeds the rate of detection by practitioners in general medical settings

(5). Social phobia is known to convey adverse social, vocational, and financial consequences and to be associated with reduced quality of life

(6,

7). Taken together, these observations underscore the need for increased attention on the part of the medical community to the public health problem presented by social phobia.

Over the years, several treatments have been shown to be efficacious for the treatment of social phobia. Among these are various specific psychological therapies

(8,

9) that, owing in part to the specialized training required by therapists and in part to inadequacies in access to care, are not widely available or accessible for most patients in many regions. Pharmacologic treatments, which are generally more available, offer physicians the opportunity to provide relief to many patients with social phobia and improve the quality of their lives. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (e.g., phenelzine) have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of social phobia

(10–

12), as have reversible inhibitors of monoamine-A (e.g., moclobemide and brofaromine) in some

(12–

15) but not all

(16,

17) studies. Similarly, high-potency benzodiazepines (e.g., clonazepam and alprazolam) have been shown to be useful for this disorder

(18). None of these medications is suitable for all patients, and accordingly, increasing interest has been focused on the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for this condition.

At the time this study was conducted there were several case studies and open-label reports of SSRIs for social phobia but only two published, small (30 or fewer subjects), single-site, double-blind studies with fluvoxamine

(19) and sertraline

(20), respectively, both of which supported the efficacy of these agents for this disorder. Recently, results of a large multicenter study of paroxetine have been published, clearly demonstrating efficacy of this agent for generalized social phobia

(21). In the present study, we conducted a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluvoxamine for the treatment of social phobia.

METHOD

Design

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for patients diagnosed with DSM-IV social phobia. Investigators at four centers in the United States participated in this 12-week study. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all centers, and the subjects gave their informed, written consent to participate. A structured clinical interview, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition

(22), was used to diagnose social phobia according to DSM-IV. After the screening procedures, each patient was randomly assigned to either placebo or fluvoxamine (at an initial dose of 50 mg of fluvoxamine per day). After 1 week the daily dose could be increased by 50 mg each week to a maximum of 300 mg/day and could be reduced at any time if side effects necessitated this (i.e., flexible dosing).

Patient Selection

Participants were recruited from patients at the investigators’ medical centers and by advertisement in local newspapers. Eligible participants, in addition to meeting the DSM-IV criteria for social phobia and having a minimum score of 20 on the Brief Social Phobia Scale

(23), were required to be between 18 and 65 years of age and to have no serious medical conditions (and be taking no medications) that might put them at risk were they to receive fluvoxamine. Patients taking psychotropic medications within the 7 days before the study were precluded from participating, as were patients with other psychiatric disorders that were deemed to be primary in terms of clinical significance (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) or patients judged to be at serious suicidal or homicidal risk. Patients receiving a specific form of psychotherapy for social phobia were ineligible. Women who were pregnant, lactating, or not using an acceptable method of birth control were ineligible. Patients with clinically significant abnormal laboratory or ECG findings were also ineligible.

Outcome Measures

The patients were evaluated at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. The primary efficacy variable was the proportion of responders at endpoint as determined by using the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI) global improvement item, by which a responder was rated as very much improved (score=1) or much improved (score=2) compared to baseline (pretreatment). The CGI global improvement rating was based solely on social phobia symptoms, not on other anxiety or depressive symptoms. The secondary efficacy variables included the mean change from baseline to endpoint in scores on three widely used, specific measures of social anxiety—the Brief Social Phobia Scale

(23), the Social Phobia Inventory (a self-rated analogue of the Brief Social Phobia Scale), and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale

(24)—and the mean change from baseline to endpoint in scores on the three subscales (work, social life, and home/family life) of the Sheehan Disability Scale

(25). Adverse events, dropout rates, and reasons for dropping out were also recorded.

Statistical Methods

Analyses of response refer to the last observation carried forward for all subjects who had evaluable efficacy data at baseline and with treatment and who had taken at least one dose of study medication. The responder analysis was conducted by using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistic with study centers as strata. Changes in baseline scores on the various efficacy measures were analyzed by using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment, center, and treatment-by-center as fixed effects. All statistical tests were two-tailed and conducted at an alpha of 0.05.

RESULTS

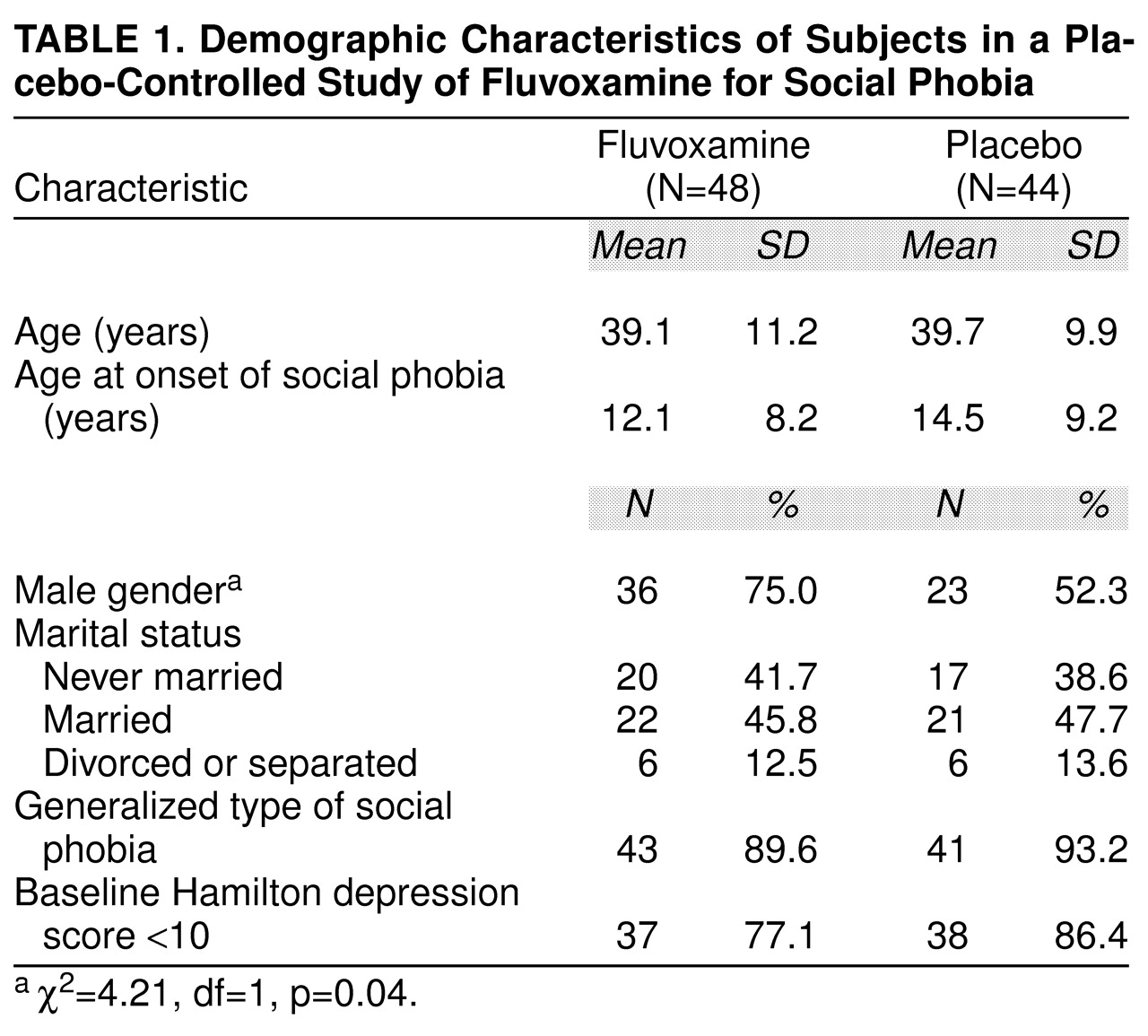

Characteristics of the patients randomly assigned to the two treatments are shown in

table 1. Consistent with most clinical samples of patients with social phobia, the subjects had an early onset of the disorder, they were predominantly male (significantly more so in the fluvoxamine group), and many had never been married. Although this was not an a priori criterion for entry into the study, nearly all of the patients (91.3%) suffered from the generalized type of the disorder, again reflecting the kinds of patients with social phobia encountered in clinical settings. Most patients had scores of less than 10 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(26), indicating low levels of depressive symptoms.

Six patients did not return for at least one subsequent assessment, leaving 86 patients (42 taking fluvoxamine and 44 taking placebo) in the evaluable study group. By study end (week 12 or with the last observation carried forward for patients who left the study earlier than week 12), 42.9% of the patients taking fluvoxamine (N=18) and 22.7% of the patients taking placebo (N=10) were deemed unequivocal responders (i.e., they had CGI improvement scores indicating “much” or “very much” improved compared to pretreatment) (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test: χ2=4.08, df=1, p=0.04). When this comparison was restricted to patients who completed the full 12 weeks of the study, the percentages of unequivocal responders were 53.3% (16 of 30) and 23.5% (eight of 34), respectively (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test: χ2=6.58, df=1, p=0.01).

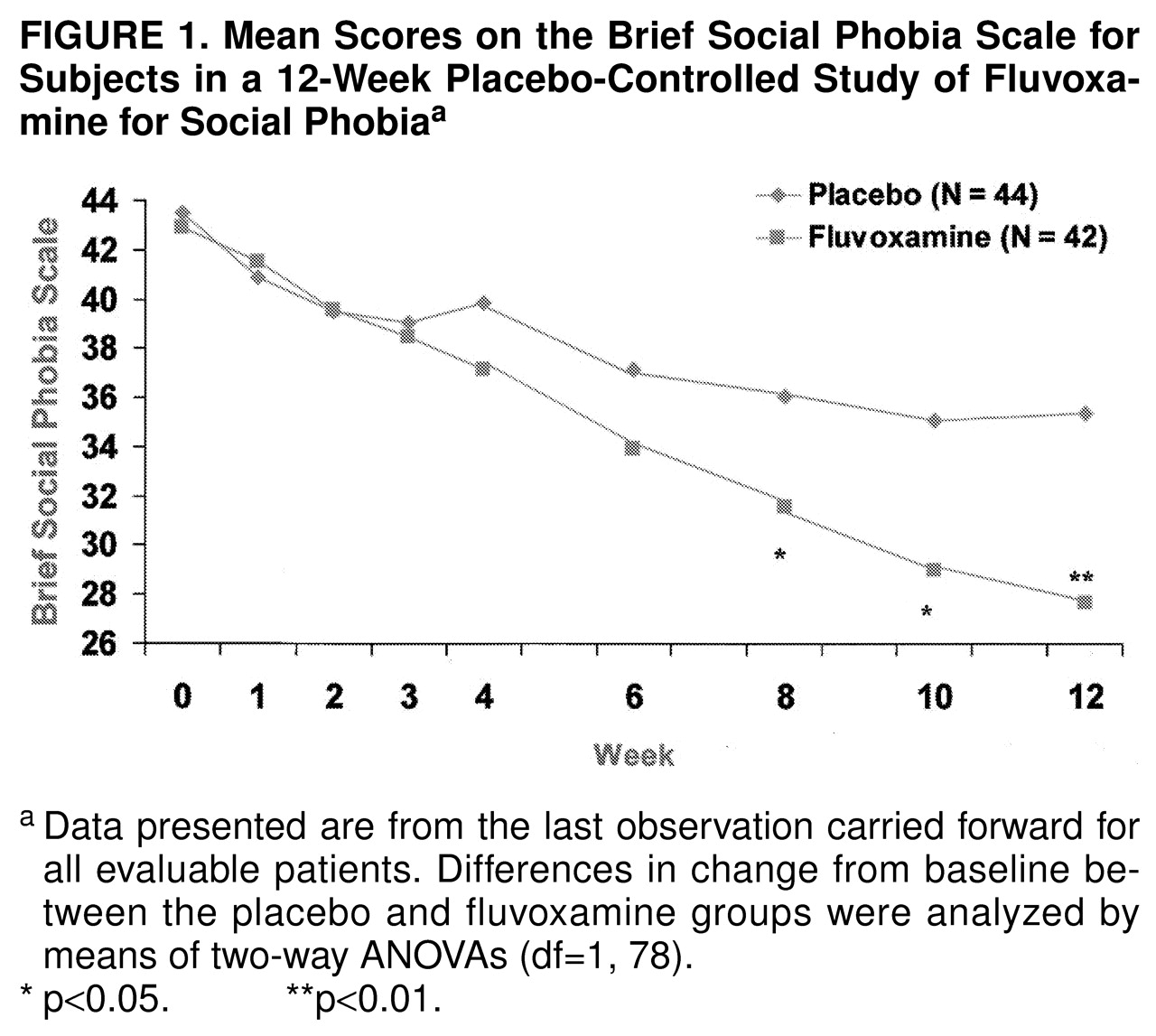

Fluvoxamine was superior to placebo in the ratings on all of the specialized social phobia rating scales. Total scores on the Brief Social Phobia Scale are shown in

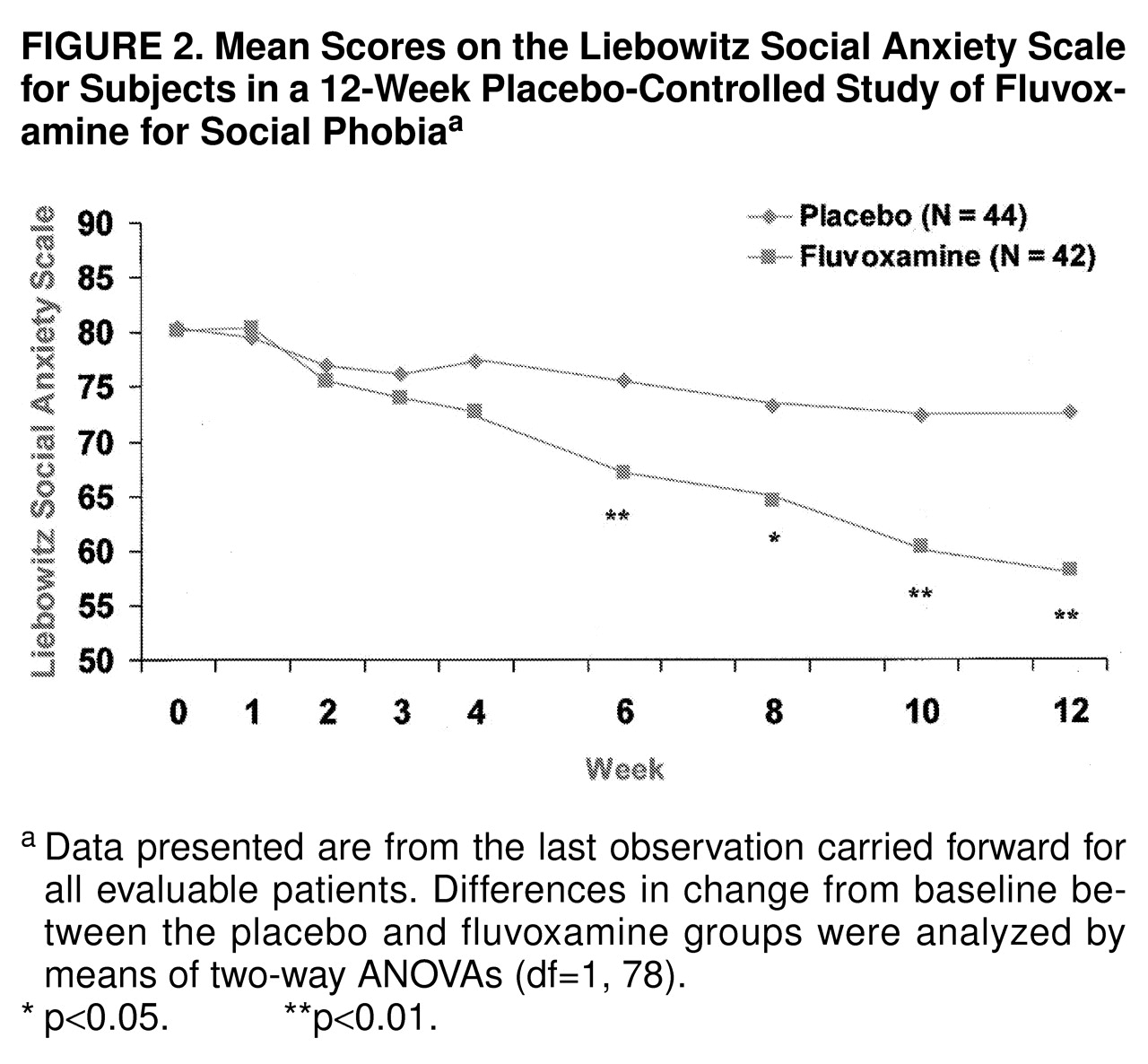

Figure 1. Fluvoxamine separated statistically from placebo at the 8-week time point and beyond. By study end the mean change in the total score on the Brief Social Phobia Scale was –15.3 (SD=13.5) for fluvoxamine and –8.1 (SD=10.7) for placebo; the difference between groups was –7.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], –12.5 to –1.9). Of interest, fluvoxamine was statistically superior to placebo on all three social phobia dimensions (i.e., fear, avoidance, and physiological symptoms) measured by the Brief Social Phobia Scale. On the Social Phobia Inventory, fluvoxamine was superior beginning at week 8. The mean scores for drug and placebo were 38.8 (SD=11.5) versus 40.0 (SD=14.1) at baseline and 27.3 (SD=14.6) versus 34.0 (SD=16.1) at endpoint (F=6.09, df=1, 78, p=0.02). Scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale followed a similar pattern of response, as shown in

Figure 2. Fluvoxamine diverged statistically from placebo at the 6-week time point and beyond. By study end the mean change in the total score was –22.0 (SD=22.7) for fluvoxamine and –7.8 (SD=19.4) for placebo (difference, –14.2; 95% CI, –23.5 to –4.9). Fluvoxamine had significantly greater effects than placebo on both subscales of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (performance and social).

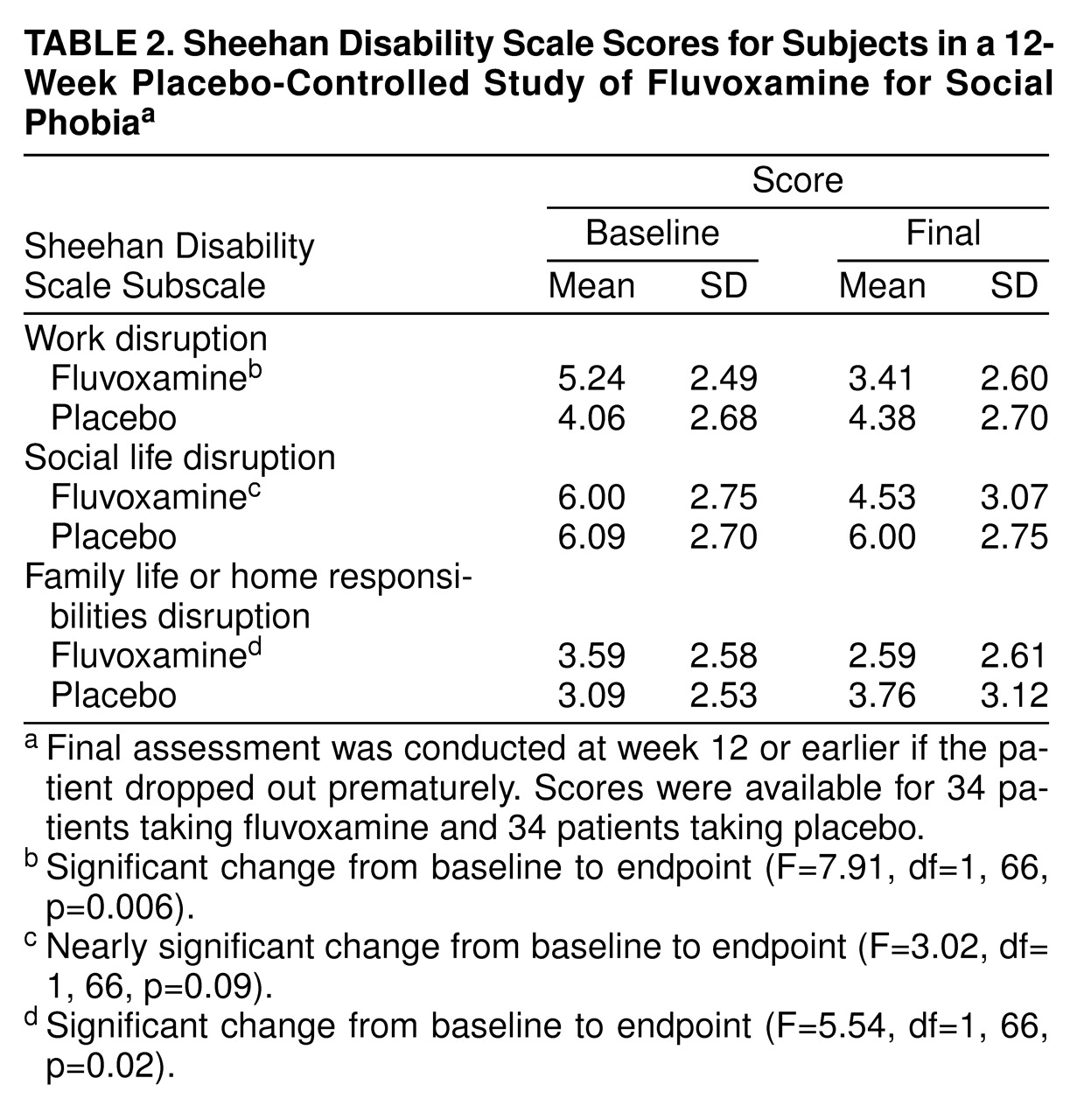

Fluvoxamine was superior to placebo on two of the three subscales of the Sheehan Disability Scale (

table 2), resulting in significant improvement in work functioning and in family life and home functioning but only a trend toward improved social life functioning.

The mean dose of fluvoxamine at study end was 202 mg/day (SD=86). At study end the patients were taking a mean of 4.03 tablets of fluvoxamine and 5.27 tablets of placebo. Fluvoxamine was generally well tolerated by the patients in the study, although more fluvoxamine-treated patients (12, 25.0%) than placebo-treated patients (N=4, 9.1%) discontinued the study early because of adverse events. The two most common side effects leading to discontinuation in the fluvoxamine group were nausea (N=5, 10.9%) and insomnia (N=5, 10.9%). Other treatment-emergent signs and symptoms for which fluvoxamine had an excess over placebo by at least 10% were dizziness, reduced libido, nervousness, and somnolence. Delayed ejaculation, a frequent complaint during SSRI treatment, occurred in four of 35 men treated with fluvoxamine (11.4%) and one of 23 men treated with placebo (4.3%). There were no unexpected or serious adverse events.

DISCUSSION

This multicenter study establishes the utility of fluvoxamine for the treatment of social phobia. Fluvoxamine resulted in unequivocal improvement of social phobia symptoms in 40%–50% of the patients, compared to approximately 25% of those who took placebo. Fluvoxamine’s reduction of social anxiety, avoidance, and associated physiologic symptoms was apparent by weeks 6–8, and improvement continued through to week 12. An important finding was that fluvoxamine treatment resulted in significant improvement on two of three indices of functional impairment, whereas placebo had no such effects. Overall, fluvoxamine was well tolerated, although nausea or insomnia resulted in premature discontinuation by 21.8% of the patients.

It remains to be determined how effective fluvoxamine—or another SSRI with demonstrated efficacy for this condition, such as paroxetine

(21)—is relative to other pharmacologic treatments for social phobia. In terms of the proportion of “responders,” the drug appears to be equal or superior to the reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase-A, such as moclobemide and brofaromine

(12–

17) (which are not available in some countries, including the United States), and somewhat less efficacious than either the MAOIs

(10–

12) or high-potency benzodiazepines

(18). At present, though, these comments are necessarily conjectural, given that direct comparisons of these agents (or meta-analyses) have yet to be conducted. Nonetheless, given fluvoxamine’s demonstrated efficacy in this and a prior study

(19), its relatively benign side effect profile, and the absence of potential for abuse or dependency, it seems reasonable to conclude that fluvoxamine should be considered among the preferred treatments for this condition. In light of preliminary evidence from this and other multicenter studies

(21) that SSRIs are probably effective in only approximately one out every two patients with social phobia, the need for adjunctive or alternative treatments for nonresponders should be systematically studied.

Among the questions left unanswered by our study and, indeed, by pharmacologic studies of social phobia in general, is the question of duration of treatment. Although we know that treatment effects mount over 12 weeks, we do not know how long an optimal therapeutic trial should last nor, importantly, how long responders should continue treatment. We do know that social phobia is a chronic condition with early onset, and so it would be surprising if a relatively brief course of treatment would result in “cure.” Accordingly, in the absence of data to the contrary, it seems reasonable to treat patients pharmacologically for 6 months or more and, in the interim, encourage patients to participate actively in their rehabilitation by performing many of the activities they had previously avoided (i.e., to do as much “exposure” as possible). When feasible, it may be advisable to offer patients additional focal psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) for their disorder, in the hope that this will promote a longer-term remission.

Finally, we wish to underscore that nearly all patients in this study suffered from the generalized type of social phobia, as is typical of the kinds of patients with social phobia encountered in psychiatric settings. It is this group that is most disabled by symptoms, most likely to experience depressive comorbidity

(27), and in our opinion, most likely to warrant pharmacologic intervention

(2). It is for this group of patients that the advent of a drug with established safety, efficacy, and lack of abuse potential is a significant advance. And it is this group of patients that, we hope, will be increasingly detected and treated by general medical practitioners now that effective, accessible treatments are available.