Over the past 15 years, researchers have argued that DSM-IV criteria are hindering investigation into the etiology, pathophysiology, and genetics of mental disorders

(1 –

3) and have proposed changes to DSM-V to make it more useful for research. These include moving from a categorical to a dimensional approach more friendly to research

(4 –

14) and adopting a “genetic nosology” that seeks to classify patients into categories that correspond to distinct genetic entities

(15) . However, because DSM must serve many masters

(16), the prospect of including diagnostic constructs useful for researchers but unfamiliar, burdensome, or of unknown utility to clinicians creates a dilemma: how can DSM-V maintain its role as a common diagnostic language facilitating research efforts without seriously compromising its clinical utility?

One possible solution is to have two versions of DSM-V: one for clinical use and the other for research. This approach was adopted by ICD-10, which provides descriptions and guidelines for clinical use and diagnostic criteria for use by researchers. Although having separate classifications would allow each to be optimized for its intended audience, maintaining divergent classification schemes would stymie communication between clinical and research communities and likely undermine the credibility of the entire diagnostic enterprise.

A better alternative is to broaden the scope of the DSM “criteria sets and axes provided for further study” appendix beyond its current role as a holding tank for proposed categories to include diagnostic constructs intended to facilitate research into the neurobiology and genetics of mental disorders. Potential candidates for this broadened appendix might include dimensional approaches judged too complex or unfamiliar for clinical use, endophenotypes not directly indicative of disorder

(17,

18), subtypes and specifiers useful primarily in research settings, and risk factors for development of disorders.

In order to maximize their research utility, these alternative diagnostic entities should be accompanied by explicit guidelines for reliable assessment. This might entail recommending existing assessment instruments or developing new ones. Moreover, these research diagnostic entities should arise out of an empirically based consensus process involving the broadest possible range of researchers to enhance “buy in” of the definitions. Furthermore, a mechanism should be established to allow for updating the appendix definitions in case they are rendered obsolete by new empirical findings. Finally, cross-walks should be developed in order to make it easier for clinicians to apply research findings based on these research diagnostic constructs to clinical practice. Cross-walking from dimensional approaches to DSM categories is conceptually straightforward, since dimensional diagnoses can be converted to categories by establishing threshold cutoff points across the dimensions

(19) . For example,

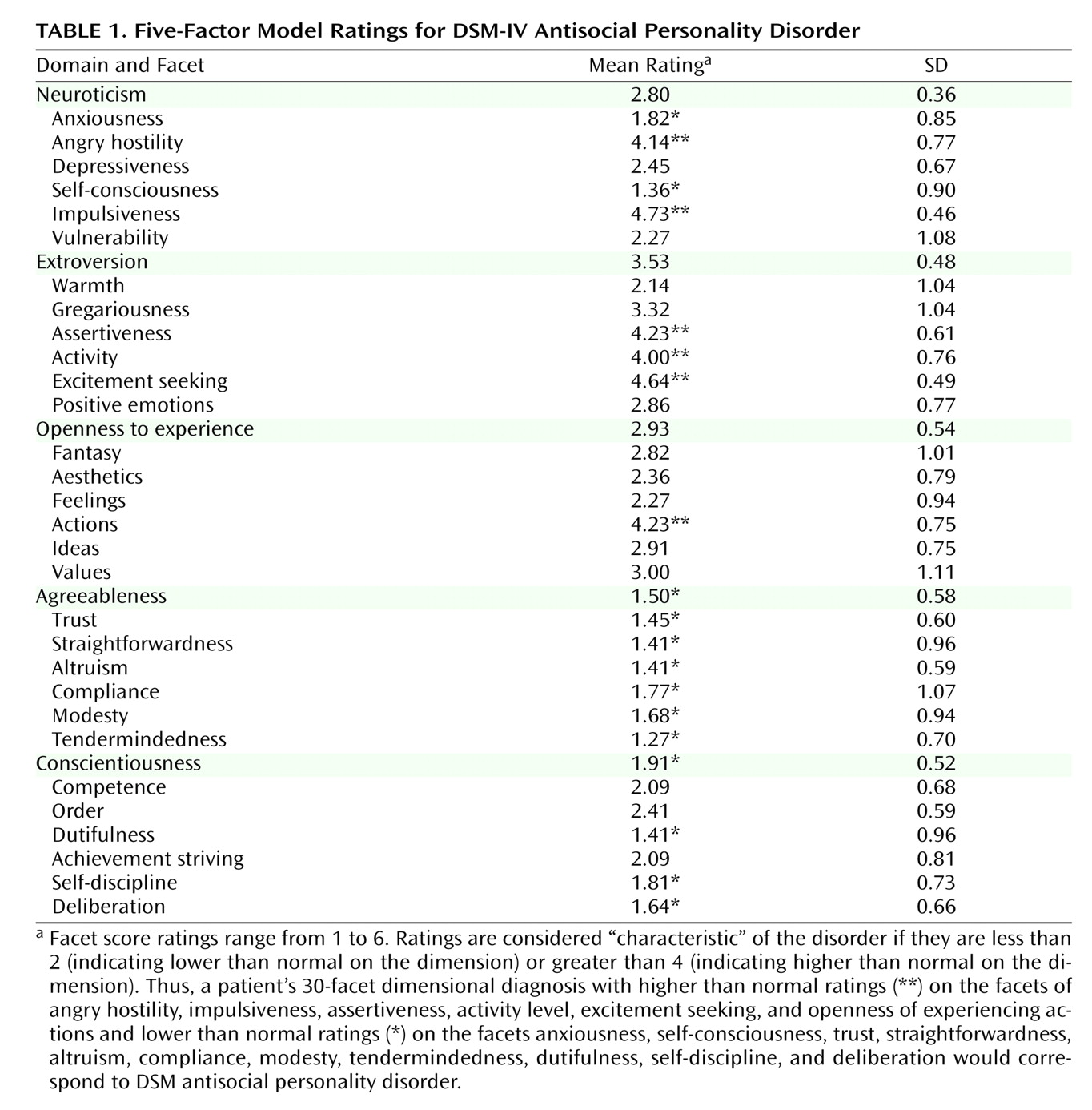

Table 1 illustrates the depiction of antisocial personality disorder in terms of the 30 facets (dimensions) of the five-factor model of personality disorder derived from an aggregation of expert ratings

(20) .

Including alternative standardized definitions in a DSM-V appendix would provide the research community with diagnostic options still contained within the “official” DSM-V umbrella and thus serve to loosen the “intellectual straitjacket” imposed by the current DSM categorical system (

21, p. 3) without creating divergent systems. A welcome side effect is that it may help “de-reify” DSM categories by highlighting their status as provisional man-made constructs open to rethinking in light of evolving knowledge, in turn helping to clarify the intended role of DSM as a useful tool for clinical practice and research rather than as the “bible” of mental disorders

(22) .