Symptom remission is the desired goal of treatment for depression, given its implications for better daily functioning and better longer-term prognosis

(1 –

6) . Since no treatment is a panacea, several sequential treatment steps are often needed to obtain remission with a tolerated treatment

(7,

8) . If a trial does not result in remission, it is an unsuccessful trial, whether due to lack of efficacy (i.e., lack of remission) or intolerable side effects, as long as the treatment is vigorously dosed to tolerance and provided for a sufficient duration to achieve remission. The number of treatment steps needed to achieve an adequate benefit is typically used to gauge the degree of treatment resistance

(9 –

13), usually with a focus on acute outcomes without reference to longer-term outcomes. Two small studies have suggested that lower acute response rates may be anticipated if patients have greater levels of treatment resistance

(14,

15) . We do not know, however, whether patients who require more treatment steps (i.e., are more treatment resistant) are different than patients who require fewer steps, nor do we know whether those who require more steps have lower remission rates, take longer to achieve remission, or have poorer longer-term outcomes.

Method

Study Overview

The STAR*D protocol provided a series of randomized controlled treatment trials in a broadly representative group of outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder who were candidates for medication as a first treatment step. If patients did not achieve remission or could not tolerate a treatment step, they were encouraged to proceed to the next acute treatment step. Those who achieved remission and tolerated acute treatment could enter a longer-term (12-month) naturalistic follow-up phase, as could those with at least a meaningful improvement and acceptable tolerability.

The organization and methods of the STAR*D trial are detailed elsewhere

(16,

17) . The study was conducted at 41 clinical sites providing primary (N=18) or psychiatric (N=23) care. Clinical sites were identified by availability of depressed outpatients, clinicians, administrative support, and large numbers of minorities. STAR*D was approved and monitored by the institutional review boards at each participating institution, a National Coordinating Center, a Data Coordinating Center, and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Participants

All participants provided written informed consent at study entry and at entry into each level and the follow-up phase. Only outpatients seeking medical care were eligible (i.e., symptomatic volunteers were excluded). Participants met DSM-IV criteria for nonpsychotic major depressive disorder at study entry as determined by clinical diagnosis and confirmed with a DSM-IV checklist by the clinical research coordinator. Participants were 18–75 years of age, not pregnant, not breastfeeding, and not previously exposed to an adequate trial of any protocol treatment within the first two treatment steps of the study. Exclusion criteria were minimal. Patients with bipolar or psychotic disorders, those with a primary diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder or an eating disorder, those with general medical conditions that contraindicated protocol medications in the first two treatment steps, and participants with substance abuse/dependence that required inpatient detoxification were excluded, as were suicidal patients who required immediate hospitalization.

Assessments

Baseline and outcome measures were collected by offsite, treatment-masked research outcome assessors via telephone, clinical research coordinators, and an interactive voice response system

(20,

21) . The research outcome assessors administered the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression (HRSD

17 ) and the clinician-rated 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C

30 )

(22 –

24) both at baseline and exit from each acute treatment level and every 3 months during the follow-up phase. Baseline HRSD

17 ratings were used to ascribe anxious features

(25), while Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology ratings ascribed melancholic

(26) and atypical

(27) features.

The clinical research coordinators at each site collected baseline sociodemographic information and self-reported psychiatric history information (personal and familial). They also administered a baseline HRSD

17 to determine study eligibility and the 14-item Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(28,

29) to gauge the number, severity, and overall burden of general medical conditions based on different organ systems. The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale identified the number of 14 possible comorbid general medical conditions (categories endorsed), the average severity score of the categories endorsed (severity index), and total severity score (the sum of severity scores across the categories endorsed). The clinical research coordinators also completed the 16-item, clinician-rated Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-C

16 )

(23,

24,

30) at each clinic visit to assess symptoms over the prior week.

Patients completed the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire, which estimated the presence of 11 different concurrent axis I disorders using a threshold of ≥90% specificity for each disorder

(31) . Patients also completed the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR

16 )

(23,

24,

30) and the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating

(17,

32) at each clinic visit. To equate HRSD

17 total scores indicating no depression (score=0–7), mild depression (score=8–13), moderate depression (score=14–19), severe depression (score=20–25), and very severe depression (score=26+) with QIDS-SR

16 total scores, a conversion table

(30) was used to provide equivalent QIDS-SR

16 ratings (no depression: score=0–5; mild: score=6–10; moderate: score=11–15; severe: score=16–20; very severe: score=21+).

The interactive voice response system collected measures of functioning and quality of life at baseline, 6 weeks, and exit from each acute treatment trial and at monthly intervals during the 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase. Interactive voice response ratings included physical and mental health functioning assessed with the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), the 16-item Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, and the 5-item Work and Social Adjustment Scale. During the 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase, the interactive voice response also collected monthly QIDS-SR

16 scores. The QIDS-SR

16 total scores obtained through the interactive voice response system correspond very closely to both the paper-and-pencil QIDS-SR

16 and the QIDS-C

16 (33) .

The SF-12, a 12-item self-report, assesses perceived mental and physical health status. Two subscales (a physical health factor score and a mental health factor score) range from 0 to 100—higher scores indicate better functioning. The population norm for each score is 50

(34) .

The Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire assesses several domains (e.g., physical health, feelings, work, household duties, school/house work). The 16-item short version was used. We summed the first 14 items to globally rate satisfaction, each of which is scored on a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the degree of enjoyment or satisfaction during the past week (1=very poor, 5=very good), and divided by the total possible score and multiplied by 100. Higher scores (range=0–100) represent greater life enjoyment and satisfaction.

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale, a 5-item self-report, assessed the ability to work, to manage affairs at home and socially, and to form and maintain close relationships. Each item is rated on a 0 to 8 Likert scale (0=no impairment at all, 8=very severe impairment; range=0–40). Scores between 10 and 20 are associated with significant functional impairment, while scores above 20 suggest at least moderately severe functional impairment.

Acute Treatment

A measurement-based care treatment approach

(19,

35) entailed the routine use of the QIDS-C

16 (obtained by clinical research coordinators) and the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating at each acute treatment visit to guide treatment as specified in a treatment manual (www.star-d.org). All acute treatment trials aimed to achieve symptom remission (QIDS-C

16 score ≤5). Those with an adequate benefit (preferably remission) per clinician judgment after any acute treatment step could enter the 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase. All patients, however, who did not reach remission were strongly encouraged to proceed to the next treatment step.

In Level 1, participants received citalopram as their first treatment step. Level 2 and 3 treatments were randomly assigned using an equipoise stratified randomized design

(16,

17,

36,

37) . Level 2 provided seven possible treatments involving four switch treatments (citalopram was stopped and new treatment initiated with sustained-release bupropion, cognitive therapy, sertraline, or extended-release venlafaxine) and three augmentation options (citalopram plus bupropion, buspirone, or cognitive therapy).

The equipoise stratified randomized design

(36) allowed patients to exercise choices over which switch or augmentation strategies were acceptable at Levels 2 and 3. For example, participants entering Level 2 could decline all three augmentation options, decline all four switch options, decline either or both cognitive therapy cells (i.e., cognitive therapy alone or cognitive therapy plus citalopram), or decline all treatments except for the two cognitive therapy cells (to ensure that they would receive cognitive therapy)

(37) . This design was used to mimic clinical practice as opposed to mandating randomization to all seven treatments (at Level 2) or all four treatments (at Level 3)

(38) .

Participants who accepted the switch strategies in the second step (Level 2) differed from participants who accepted the second step augmentation strategies. As a group, they tended to be more severely ill and to have experienced more side effects with citalopram

(39) . Only 21 of 1,439 Level 2 participants accepted randomization to all seven treatments.

For the most part, patients who had not achieved remission or were unable to tolerate their assigned second step (Level 2) treatment could subsequently enter Level 3 directly. Level 3 included two medication switch strategies (mirtazapine or nortriptyline) or two medication augmentation strategies (lithium or T 3 [25 mg]). Once again, many Level 3 participants elected either the augmentation or switch strategy, although both strategies were encouraged.

Level 4 entailed only a single randomization to either tranylcypromine or extended-release venlafaxine plus mirtazapine. For most patients, the third and fourth treatment steps corresponded to Levels 3 and 4.

For those who received cognitive therapy alone or combined with citalopram in Level 2, however, the third treatment step was a special Level 2A, required only for participants who did not achieve remission or were unable to tolerate either cognitive therapy alone or cognitive therapy plus citalopram in Level 2. Level 2A, which involved random assignment to either bupropion or venlafaxine, was included to ensure that all participants who entered Level 3 had not adequately benefited from two different medication trials. Consequently, for this subgroup, the fourth treatment step (when needed) consisted of Level 3 treatments. A few patients (N=3) received cognitive therapy or cognitive therapy plus citalopram at Level 2, then Level 2A, and then Level 3, before progressing to a fifth treatment step (i.e., Level 4). We will not report on this group.

The multistep protocol allowed all eligible and consenting Level 1 enrollees to enter Level 2 (or subsequent levels) if they were not in remission or could not tolerate citalopram (or subsequent treatments). All Level 1 enrollees had to score ≥14 on the HRSD 17 as rated by the clinical research coordinator. Some of these patients did not have an HRSD 17 obtained by the research outcome assessor at entry into Level 1. Nevertheless, these participants could and did enter Level 2. Participants who entered Levels 2, 2A, 3, or 4 were not required to meet criteria for a major depressive episode at that time since some could have experienced significant symptom reduction that fell short of remission.

Naturalistic Follow-Up Phase

Protocol-recommended treatment visits during the follow-up phase were to occur every 2 months. In the follow-up phase, the protocol strongly recommended that participants continue the previously effective acute treatment medication(s) at the doses used in acute treatment but that any psychotherapy, medication, or medication dose change could be used. Medication management was based on clinician judgment, typically without clinical research coordinator support.

Definition of Outcomes

We used the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR

16 ) as the primary measure to define outcomes for acute and follow-up phases because 1) QIDS-SR

16 ratings were available for all participants at each acute treatment clinic visit, 2) QIDS-SR

16 and HRSD

17 outcomes are highly related

(19,

30,

37 δ2), 3) the QIDS-SR

16 was not used to make treatment decisions, which minimizes the potential for clinician bias, and 4) the QIDS-SR

16 scores obtained from the interactive voice response system, the main follow-up outcome measure, and the paper-and-pencil QIDS-SR

16 are virtually interchangeable

(33), which allows us to use a similar metric to summarize the acute and follow-up phase results. Response was defined as at least a 50% reduction from treatment step entry in QIDS-SR

16 score. Remission was defined as a QIDS-SR

16 score ≤5 (corresponding to an HRSD

17 score of ≤7)

(33,

41) . Relapse was declared when the QIDS-SR

16 score collected by the interactive voice response system during the follow-up phase was ≥11 (corresponding to an HRSD

17 ≥14)

(30) . Time to remission for those who remitted was defined as the time (in weeks) from initiating a treatment at the relevant treatment step to the first occasion at which the QIDS-SR

16 score was ≤5.

Patients were defined as treatment intolerant if they left the relevant acute treatment step prior to 4 weeks of treatment for any reason, or if the reason for leaving was not obtained (which was the case for the vast majority of patients), or if they left the step after 4 weeks and the treatment step exit form indicated intolerance.

For this report, we created successive subsets of the study sample, including those participants who entered each treatment step, and grouped participants by the number of treatment steps they had taken. Since a patient could have entered one or more of the several treatment steps, these subsets are not mutually exclusive. We describe the clinical and demographic features of each subset to characterize those patients who entered each treatment step. We then report the overall acute symptom outcomes (e.g., remission rates) associated with each acute treatment step and describe the longer-term outcomes of the 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase for each group. Finally, we assess the relationship between remission at follow-up entry and the likelihood of relapse following each treatment step.

Analyses

Summary statistics are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for discrete variables. Analysis of variance was used to compare QIDS-SR 16 scores at entry to follow-up across treatment steps. Chi-square tests were used to compare the percentage of patients in remission at entry into the follow-up phase across treatment steps as well as relapse rates in follow-up across treatment steps. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to compare the cumulative proportion not experiencing relapse across treatment steps, overall, and stratified by remission status at entry to follow-up. For significant findings, post hoc tests were conducted by making pairwise comparisons of treatment steps with Bonferroni corrections.

Results

The overall acute treatment findings based on the protocol-defined level of treatment are reported elsewhere

(19,

37 –

40,

42) . The remission rate per QIDS-SR

16 score was 32.9% for the evaluable Level 1 patient group

(19) . For the intent-to-treat group, the remission rates per QIDS-SR

16 score were 30.6% for Level 2, 13.6% for Level 3, and 14.7% for Level 4.

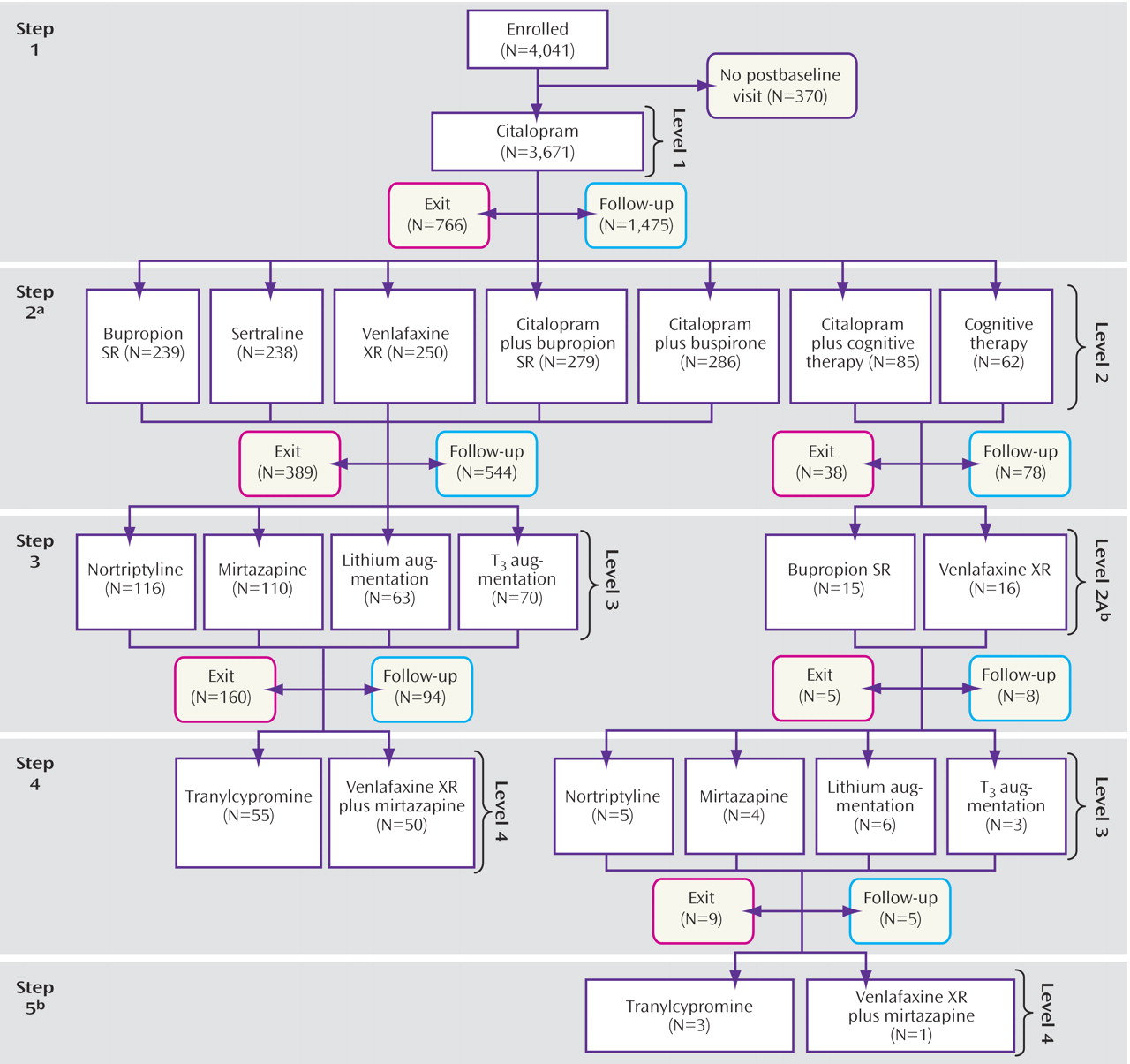

For this report, we combined the patients who enrolled in the various protocol-defined treatment levels into groups defined by the number of prior treatment steps (

Figure 1 ). Overall, 4,041 participants were enrolled in the STAR*D study. All participants had to have scores ≥14 on the HRSD

17 as obtained by the clinical research coordinator at study entry. We excluded 370 of these participants because they did not return for a postbaseline assessment in Level 1, leaving 3,671 participants. (Note: this sample includes the 2,876 reported in Trivedi et al.

[19] plus those patients whose HRSD

17 score per research outcome assessor was <14 at entry and who had at least one postbaseline visit. These latter participants were excluded from Trivedi et al.) Overall, 1,439 participants entered the second step, and 390 had a third treatment step, either Level 3 treatment (N=359) or Level 2A (N=31). Only 123 participants had a fourth treatment step (105 of whom entered Level 4, and 18 of whom entered Level 3).

Acute Treatment Outcomes Associated With the Various Acute Treatment Steps

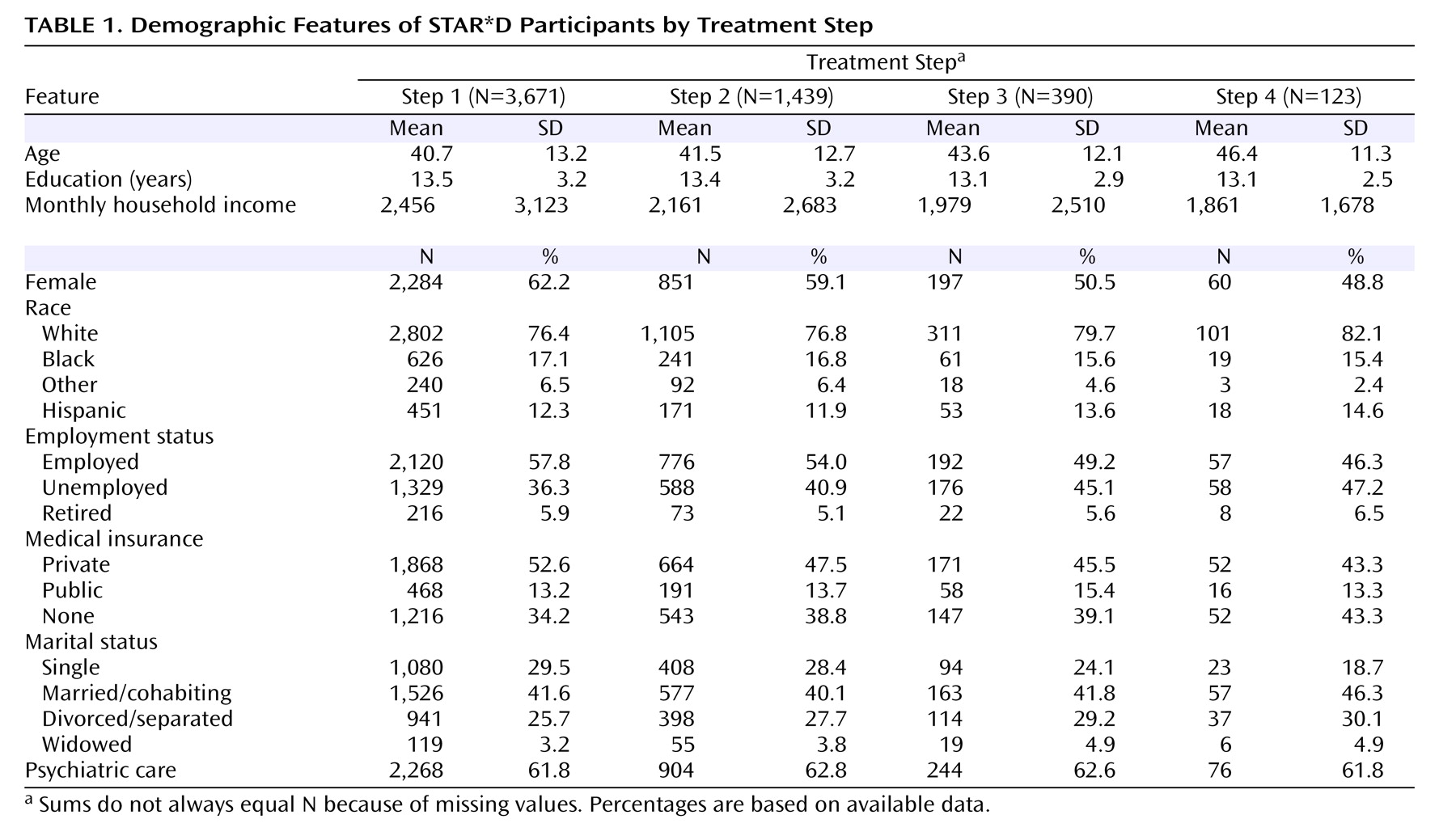

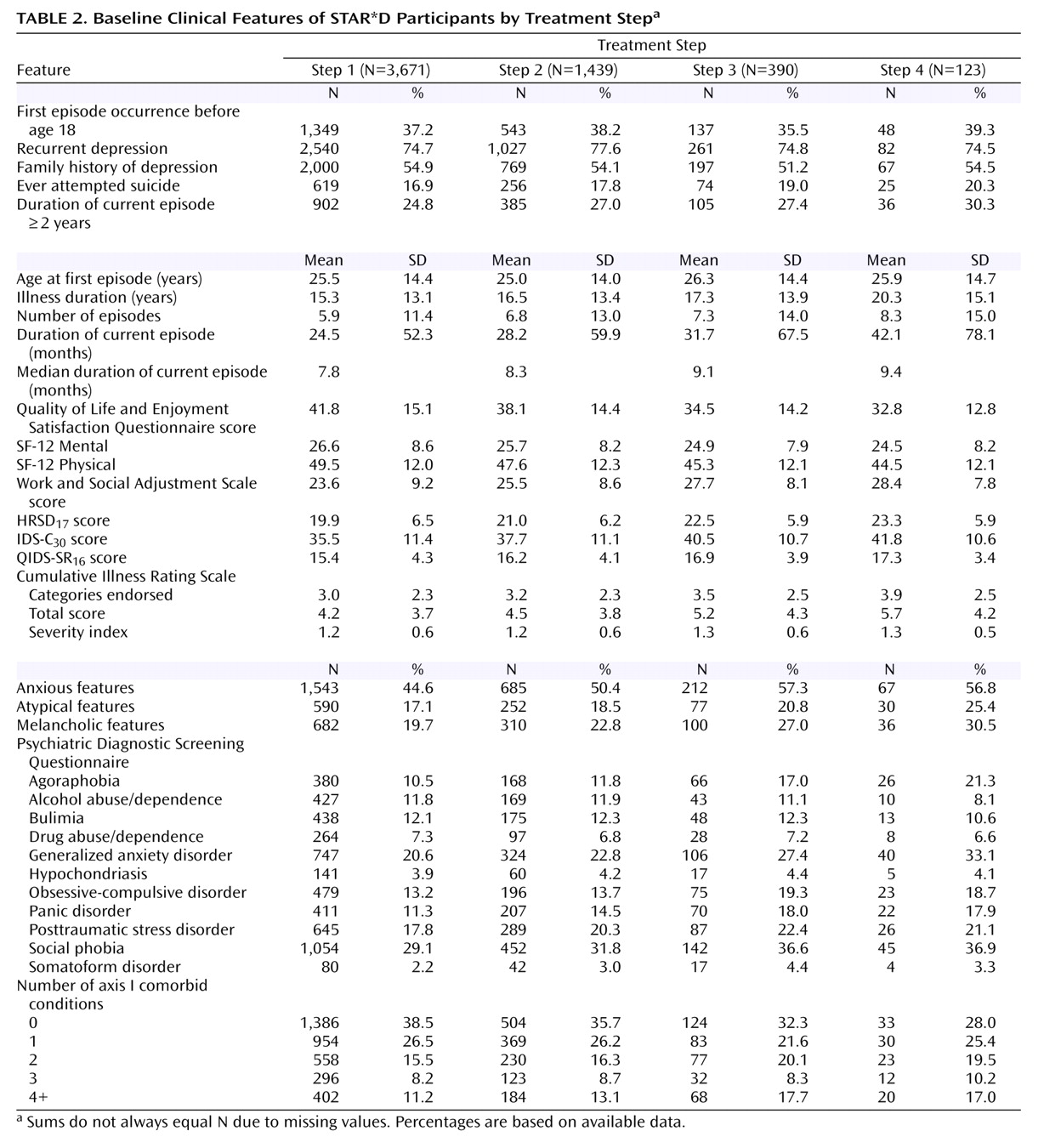

Table 1 and

Table 2 describe the demographic and clinical features of the successive subsets of participants who entered treatment steps 1, 2, 3, and 4. As can be seen, participants who required more treatment steps tended to have greater depressive illness burden and more concurrent psychiatric and general medical disorders.

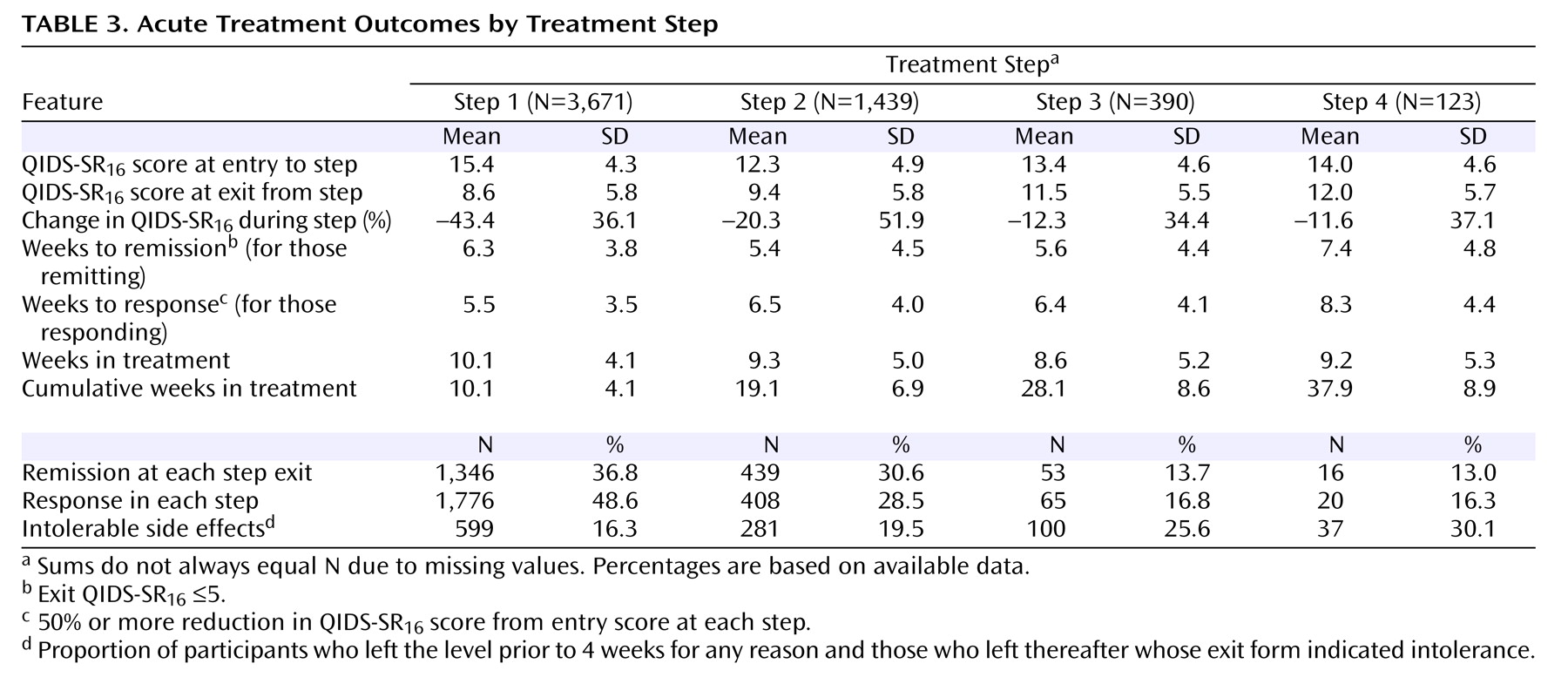

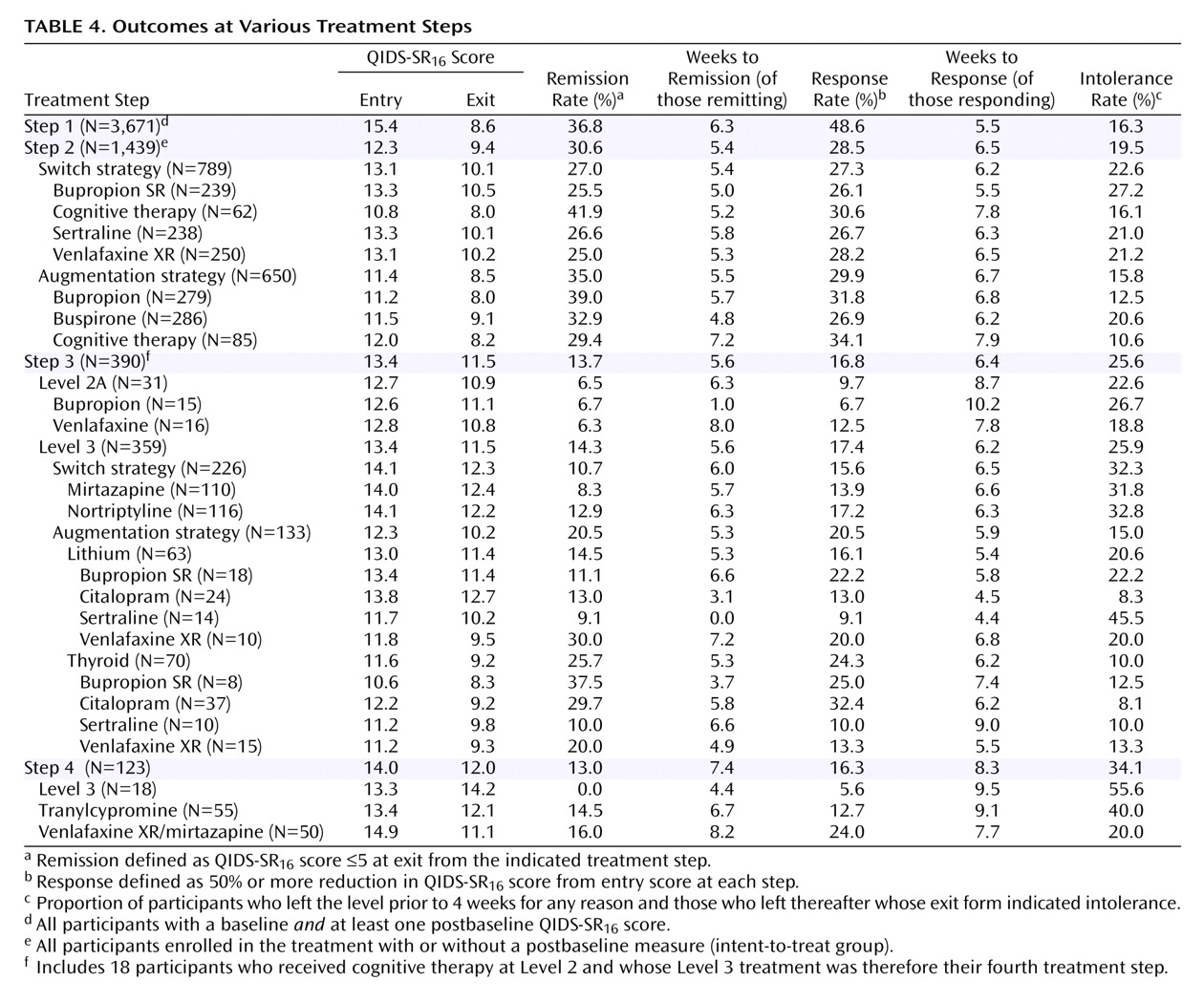

Table 3 shows the status at entry and exit for each acute treatment step. The earlier treatment steps were associated with higher remission rates. For those who achieved remission at each step, the times to remission were 5.4 to 7.4 weeks across the four treatment steps. In addition, rates of intolerance seemed to be greater in the later steps. To determine whether remission rates might differ depending on prior treatment history before study entry, we compared the remission rates in the first and second treatment steps between those who had and had not received treatment for their current major depressive episode before study entry (we did not obtain prior treatment history other than for the current episode). For step 1, those not previously treated for their current episode (N=614) had a 42.7% remission rate compared with a 35.6% remission rate in those who had been treated (N=3,057). For the second step, the remission rates were comparable for those not treated (N=185) and those who were treated (N=1,254) for their current major depressive episode (remission rates of 30.7% and 30.3%, respectively).

Table 4 shows the overall entry and outcome values for participants in each treatment step and by the type of treatment used in each step. Of note, those in Level 2A (having received cognitive therapy alone or combined with citalopram at Level 2) had very modest remission rates with venlafaxine or bupropion. Note that one cannot compare the remission rates with augmentation versus switch at either steps 2 or 3, since these are not randomized samples (i.e., largely different patient groups received switch or augmentation).

The cumulative remission rate can be estimated by assuming that 100 patients begin citalopram treatment. Overall, 36.8 will achieve remission in step 1, leaving 63 to proceed to the next step. In step 2, 30.6% (N=19) will remit (.306×63 = 19). In the third step, 13.7% or N=6 will remit (.137 x [100–37-19]). In the fourth step, 13.0% or N=5 will remit. The theoretical cumulative remission rate is 67% (37+19+6+5). Note that this estimate assumes no dropouts, and it assumes that those who exited the study would have had the same remission rates as those who stayed in the protocol.

Longer-Term Outcomes Associated With Each Treatment Step

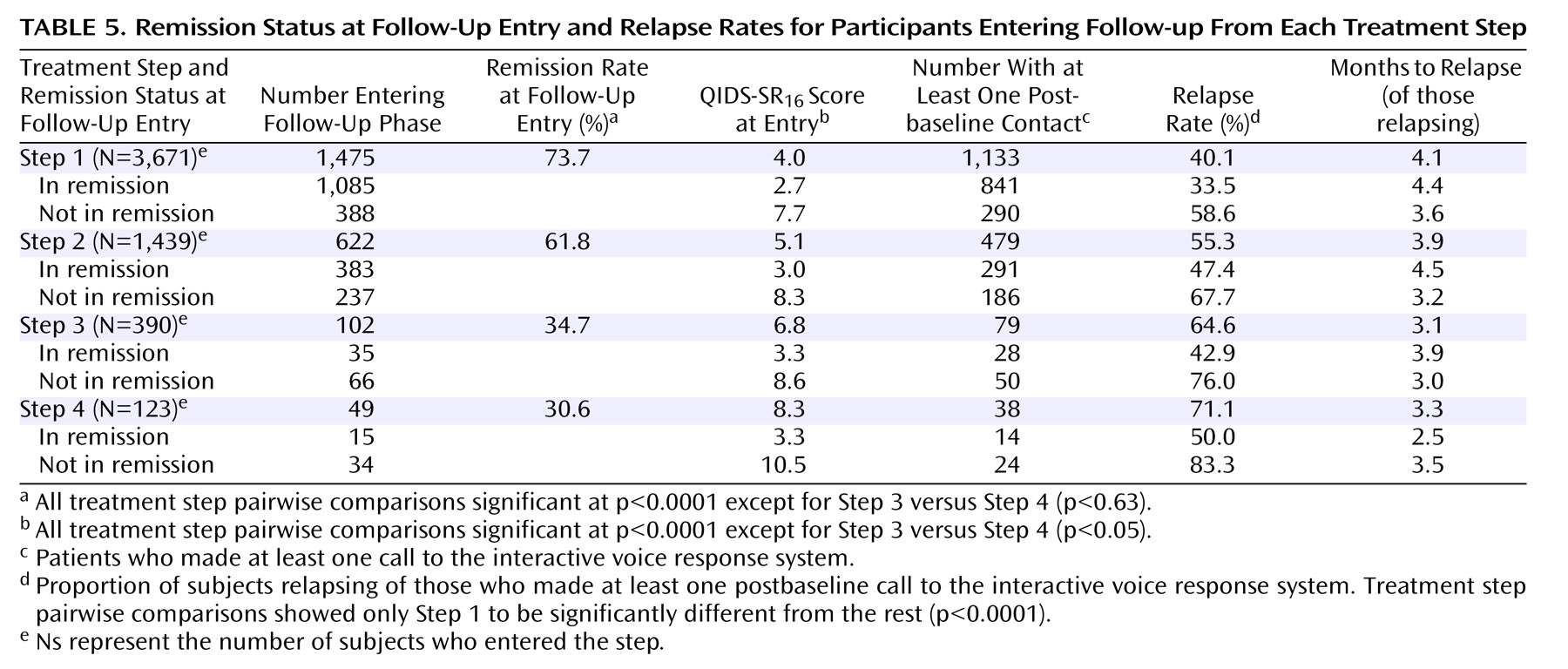

Table 5 shows that at follow-up entry, participants from the later treatment steps were less likely to be in remission (p<0.0001), and they had higher QIDS-SR

16 scores (p<0.0001) at entry into follow-up. Relapse rates were higher for those who entered follow-up after more treatment steps (p<0.0001).

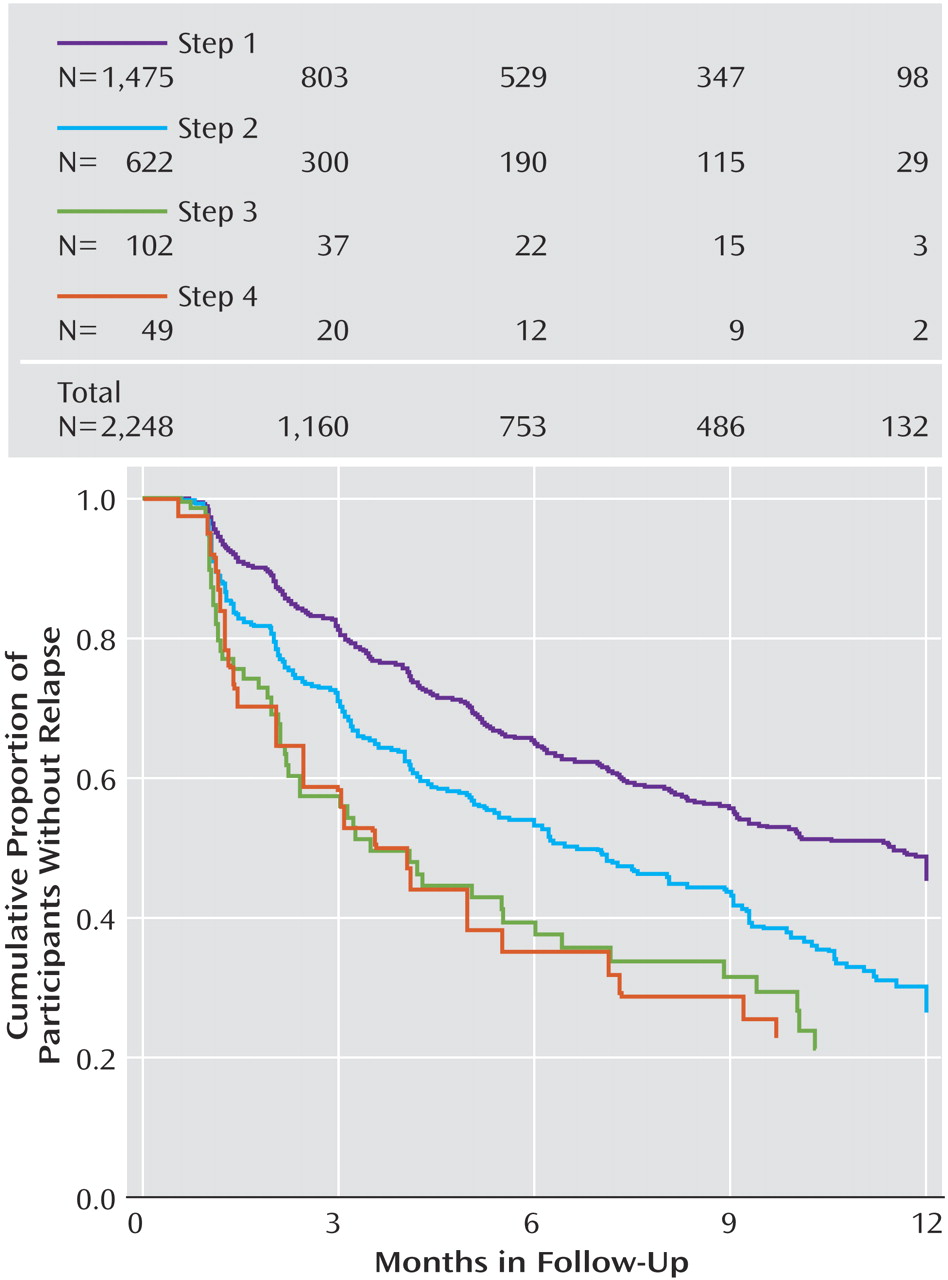

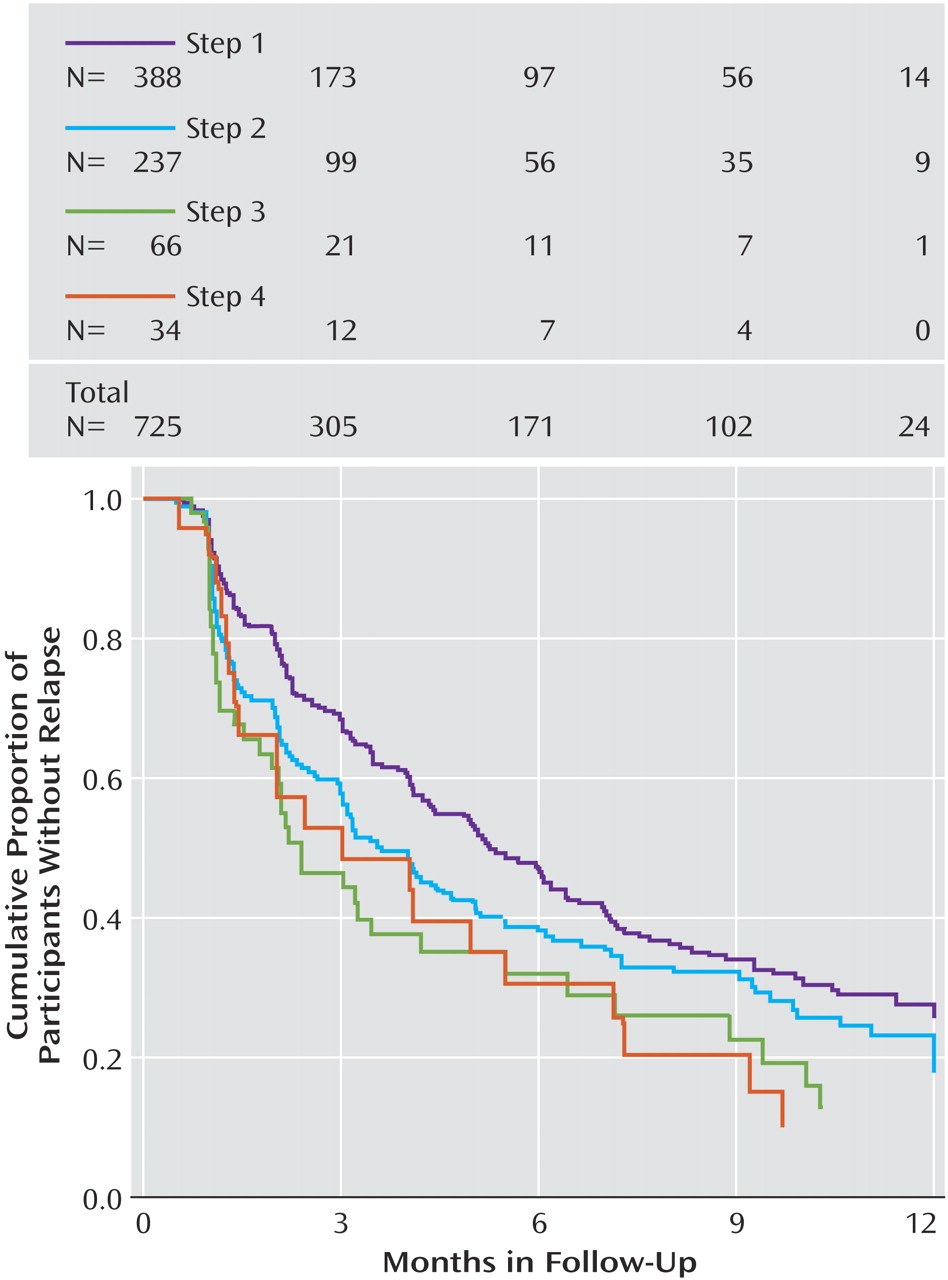

To further explore these follow-up findings, we evaluated the probability of relapse (QIDS-SR

16 score obtained by interactive voice response ≥11) using survival analyses (

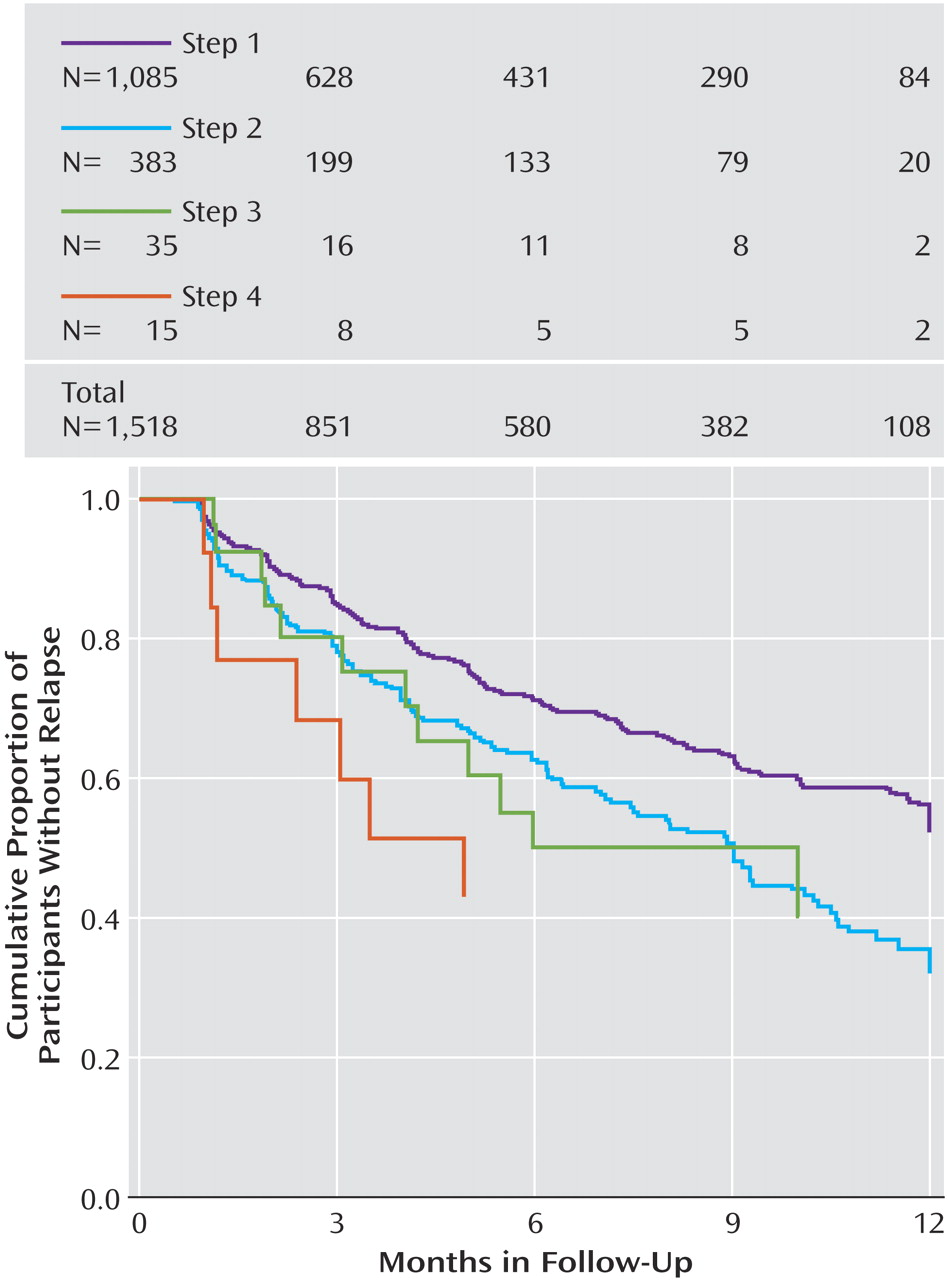

Figure 2 ). Overall, relapse rates were higher for those who entered follow-up after more treatment steps. Recall that participants could enter the follow-up phase if they reached remission or had adequately benefited but had not reached remission. In this context, the higher relapse rates found in patients with more acute treatment steps could be due to the greater nonremission rates among those who required more treatment steps. To address this issue, we divided participants into those who had and had not reached remission at follow-up entry (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 ). Once again, for participants who either had or had not achieved remission at follow-up entry, we found higher relapse rates among those who required more treatment steps.

Discussion

This report summarizes the acute and longer-term STAR*D trial findings based on the number of acute treatment steps needed to achieve an adequate benefit as defined by clinicians using a measurement-based care approach

(19) in a large, representative group of depressed adult outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder. The acute remission rates (per QIDS-SR

16 score) were substantial for the first two treatment steps (which correspond to the first two protocol levels): 36.8% for step 1 and 30.6% for step 2. The latter steps (3 and 4) were each associated with lower QIDS-SR

16 remission rates (13.7% and 13.0%, respectively). Theoretically, had all the patients stayed in treatment and had those who exited the study had remission rates similar to those who stayed in protocol treatments, the overall cumulative remission rate would approach 70% after four steps (if needed). The time to remission in those who did remit seems to have been slightly greater for those who required more treatment steps. These prospective data provide a benchmark (at least with the treatments studied) for practitioners.

In addition, the acute treatment step findings highlight the importance of retaining patients in treatment. Despite the availability of the clinical research coordinator, free treatment, and diligent care, the percent of patients exiting after each step was clinically meaningful (20.9% after step 1, 29.7% after step 2, 42.3% after step 3).

What might explain the substantial numbers of patients who did not achieve remission in acute treatment? There may be some kinds of depression for which our treatments (at least the ones under study) cannot produce remission (independent of the chronicity and comorbid conditions that were present). Conversely, the presence of comorbid general medical or psychiatric disorders may be associated with or induce biological changes that render our otherwise useful treatments ineffective. Perhaps these patients would have benefited from earlier application of different treatment approaches (e.g., ECT, vagus nerve stimulation, repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation, augmentation with atypical antipsychotic medication, etc.). Alternatively, perhaps those with more chronic depression, had they been treated earlier in the course of their illness (i.e., before chronicity had developed), might have remitted with the treatments used in this study

(43) . The present data cannot determine which of these explanations is valid. These data do suggest that clinicians need to attend especially to those with more chronic depression, combined with more concurrent general medical and psychiatric disorders.

The follow-up results revealed 1) remission at entry into follow-up was associated with a better prognosis than was simple improvement without remission, 2) relapse rates were higher for participants who entered follow-up after more versus fewer acute treatment steps regardless of remission status at follow-up entry, and 3) the mean time to relapse for those who did relapse was shorter for those who required two or more steps. Whether a particular treatment in each treatment step is associated with a different longer-term outcome and whether baseline clinical features predict longer-term outcomes will be reported subsequently.

The clinical implications of these findings are profound. Remission is the accepted goal of acute treatment

(6,

7,

16,

17,

44 ε7) because remission is associated with better day-to-day function

(1) and a better prognosis

(2 –

5) . These conclusions, however, are based largely on depressed patients who have responded or remitted after only one treatment step. The present findings indicate that remission is associated with a better prognosis even if remission is reached after several treatments. In addition, the chance of attaining remission was lower when more acute treatments were needed (at least with the treatments and treatment sequences used in this study). Thus, in terms of acute treatment, clinicians must weigh the benefit already achieved with the initial (or subsequent) acute treatments against their estimates of the probability of reaching remission and the potential side-effect burden associated with undertaking the next treatment step for each patient. Specifically, clinicians (with patients) must decide when remission (given our current treatments) is sufficiently unlikely that subsequent alternative treatments should be considered.

Second, the present results indicate that even following antidepressant response or remission, diligent follow-up treatment is called for, particularly in the first several months and especially for patients who enter follow-up treatment not in remission, since the risk of relapse in this time period is high, especially for those who have received three or four acute treatment steps.

These results also have provocative theoretical implications. The findings are suggestive that major depressive disorder is biologically heterogeneous such that different treatments differ in the likelihood of achieving remission in different patients. However, without a placebo control at each step and without substantial differences in remission rates among treatments in the same step, such a notion remains to be fully established. It does appear that those with a more prolonged or chronic illness course (i.e., overall length of illness and length of the current episode), and those with more concurrent general medical and psychiatric comorbidity may be less likely to achieve remission with acute treatment. The present results serve to highlight the need for more effective short- and longer-term treatments to both achieve and sustain remission in more depressed patients sooner in the treatment sequence.

Study limitations in this report include reliance on a self-report (the QIDS-SR

16 ) as the primary outcome, although the high correlation between the QIDS-SR

16 and the HRSD

17 (19,

33,

37,

39,

41) mitigates this concern. Second, neither clinicians nor participants were blind to the treatments or to the results achieved with each treatment step. On the one hand, this open treatment design likely encouraged vigorous dosing of medications, enhanced safety, and mimicked practice. On the other hand, while the doses in this study do represent high quality of care, they likely exceed the doses commonly used in practice. Finally, a placebo control was not used in any step. Consequently, we cannot rule out the possibility that the passage of time alone might not have produced similar results.

The generalizability of our findings can also be questioned. The broadly representative study group provides results for a broadly defined cohort of patients. Better (or worse) outcomes might be achieved with particular subgroups (e.g., less chronically ill, only insured and employed patients, etc.). Furthermore, these findings were obtained in the context of a series of randomized controlled trials that required participants to provide written informed consent at entry into each acute treatment step and into the follow-up phase, which might limit generalizability.

Many participants did choose to exit the study rather than electing to take the next protocol treatment step. Whether these patients would have had similar results had they remained in the study is unknown, although most of them were in need of additional treatment because most who exited were not in remission (approximately 80%) at the time of study exit. Third, despite the 12–14 week duration of each acute treatment step, one might also argue that at least some patients would have achieved remission had they been treated longer. Such patients, it can be argued, should not have moved to the next step. That is, even longer acute trial durations than used in this study might have increased the remission rates associated with each step. We will subsequently report on the follow-up outcomes for those patients who entered the follow-up phase without having remitted to determine what proportion ultimately remitted. Finally, high quality of care was delivered (measurement-based care)

(19) with additional support from the clinical research coordinator. Consequently, the outcomes in this report may exceed those that are presently obtained in daily practice wherein neither symptoms nor side effects are consistently measured and wherein practitioners vary greatly in the timing and level of dosing.