Major depressive disorder is a common and recurrent disorder in children. It is frequently accompanied by poor psychosocial outcome, comorbid conditions, and high risk of suicide and substance abuse, indicating the need for treatment. The prevalence of major depressive disorder is estimated to be approximately 2%–4% in children

(1) . Several randomized, controlled studies have shown a 50% to 60% response to both selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo

(2,

3) . However, these studies included a majority of adolescent children, and the efficacy of biological treatment of prepubertal childhood depression is almost unknown. We found omega-3 fatty acids to be effective in adult depression as an add-on therapy

(4) . We therefore performed a controlled study of omega-3 fatty acid in childhood depression, restricting our study to children between the ages of 6 and 12.

Method

Subjects were children referred to the depression clinic at the Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel or the Child Psychiatry Clinic of the Beer-Sheva Mental Health Center. Children suffering from major depressive disorder using the Hebrew translation of the childhood version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia

(5) were accepted. Excluded were children with unstable physical illness or psychiatric disorders other than anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dysthymia, or tic syndrome.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the faculty of health sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel, and of the Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel. All participating patients entered the study after at least one parent’s written informed consent, following the child’s verbal informed consent and after the consenting parent’s commitment to inform the other parent.

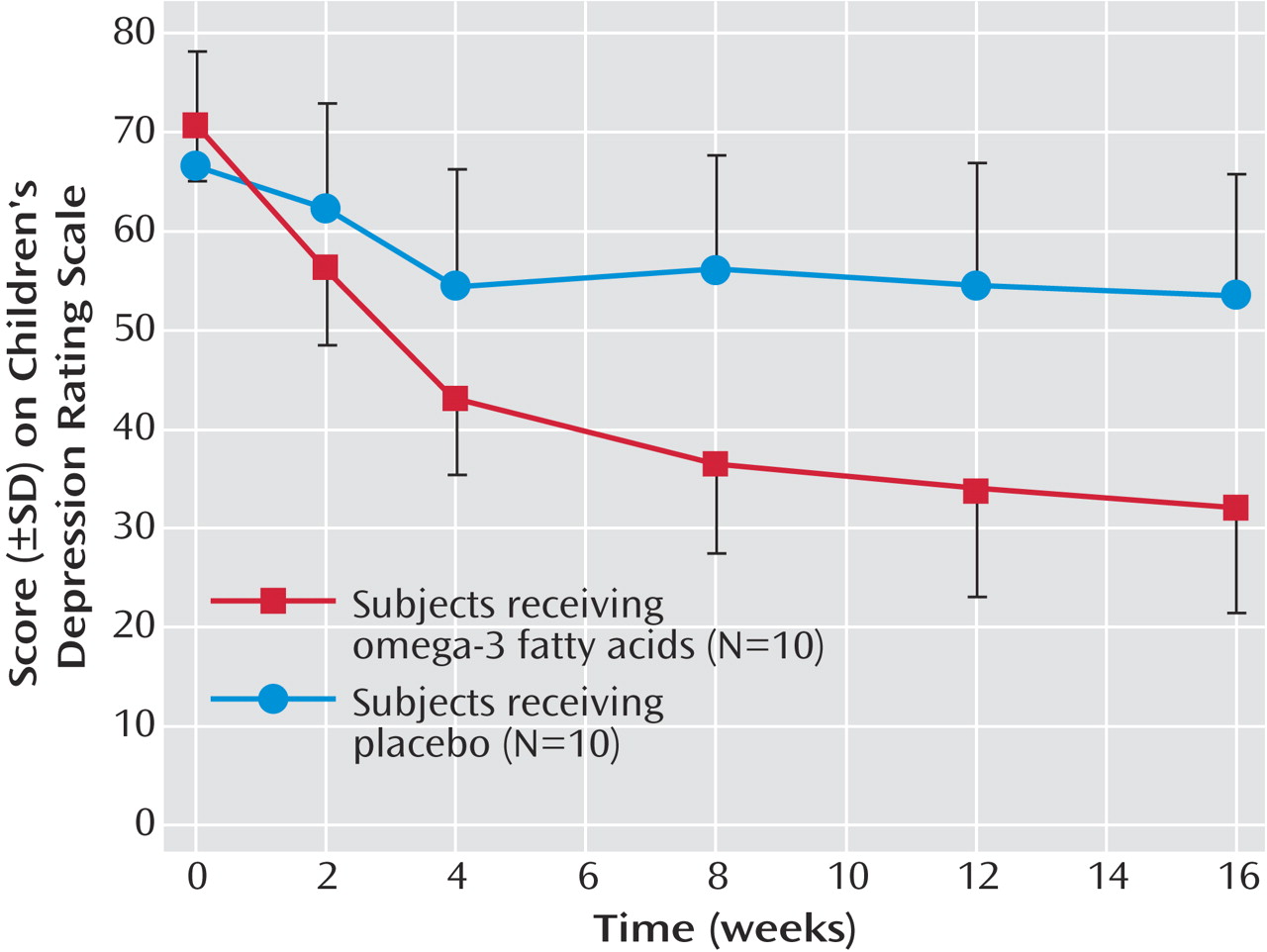

The omega-3 trial lasted for 16 weeks. Ratings were made at baseline and at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks using the Childhood Depression Rating Scale (CDRS), Childhood Depression Inventory (CDI), and Clinical Global Impression (CGI). The CDRS and CGI are clinician rated, whereas the CDI is self-rated by the child-patient at each visit.

Patients received two 500 mg or one 1,000 mg capsule daily, depending on their ability to swallow a larger capsule. This was chosen as one-half of the adult dose used in our previous study

(4) . Placebo for the 500 mg capsule was olive oil (supplied by Ocean Nutrition, Canada) containing no omega-3 fatty acids. Placebo for 1,000 mg capsules was safflower oil (74% linoleic acid supplied by Sears laboratories containing no omega-3 fatty acids). The 1,000 mg active capsules were supplied by Sears Laboratory containing 400 mg eicosapentanoic acid and 200 mg docosahexaenoic acid per 1,000 mg capsule. The 500 mg active capsules supplied by Ocean Nutrition contained 190 mg eicosapentanoic acid and 90 mg docosahexaenoic acid per 500 mg capsule. These ratios of eicosapentanoic acid to docosahexaenoic acid are similar to most commercially available preparations but different from the pure eicosapentanoic acid used in our earlier study. Active and placebo capsules were identical in shape, markings, and appearance except for a slight difference in tone of internal color, which could be distinguished only by an experienced observer familiar with both types of capsules and able to compare them simultaneously.

Results

Twenty-eight children were randomized for the study. Of these 28, 20 completed at least 1 month’s ratings and were included in the data analysis. Of the eight who dropped out before 1 month, five were on placebo and three were on omega-3. Among the three children of the omega-3 group, the only reason for dropout before 1 month was noncompliance. Reasons for dropout before 1 month in the placebo group were 1) appearance of precocious puberty leading to an endocrine workup in one patient, 2) noncompliance in two patients, 3) nonresponse in one patient, and 4) manic episode in another patient.

Of the 20 children who entered data analysis, 10 received placebo and 10 received omega-3. There were seven boys and three girls in the placebo group and eight boys and two girls in the omega-3 group. Mean age in the omega-3 group was 10.0 (range: 8−12.0) and 10.3 in the placebo group (range: 8−12.5). Children had been depressed for a mean of 3.5 (SD=1.3) months in the omega-3 group and 3.3 (SD=1.6) months in the placebo group. This was a first depressive episode in all cases. In the omega-3 group, there were two children with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, one with obsessive-compulsive disorder, one with separation anxiety, one with dysthymia, and one with chronic tics. In the placebo group, there were three children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, one with panic disorder, one with separation anxiety, and two with dysthymia. Concurrent medications on stable dose for at least 6 months were two children on methylphenidate in the omega-3 group and three children in the placebo group.

Figure 1 shows the CDRS scores in the 20 patients who completed at least 1 month, with the last value carried forward. The effect of omega-3 is highly significant. Among the children on omega-3 treatment, seven out of 10 had a greater than 50% reduction in CDRS scores. Of those on placebo, zero out of 10 had a greater than 50% reduction in CDRS scores (p=0.003, Fisher’s exact test). Four out of 10 children in the omega-3 group met the remission criteria of Emslie and colleagues

(2) of a CDRS score <29 at study exit; no subject in the placebo group met this criteria (p=NS).

The self-rating CDI results were similar to those of the CDRS. The “N” in the placebo group was 8 because two patients were unable to complete the self-rating scale or did so with errors. Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance of treatment over time showed a statistically significant interaction (F=3.4, df=5,80, p<0.005). In addition, there was a significant main effect of treatment (F=5.5, df=1,16, p<0.04) and time (F=7.6, df=5,80, p<0.001).

CGI results were also highly significant. Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance of treatment over time showed a statistically significant interaction (F=10.0, df=5,90, p<0.0001). There was a significant main effect of treatment (F=27.0, df=1,18, p<0.001) and time (F=28.3, df= 5,90, p<0.0001). The omega-3 group and the placebo group were significantly different at week 8 (least significant difference post hoc test, p=0.014), week 12 (least significant difference post hoc test, p=0.003), and week 16 (least significant difference post hoc test, p=0.002).

There were no clinically relevant side effects reported. No patient reported a fishy taste when asked specifically. Debriefing of the blind revealed a random guess rate by both patient and clinician.