The aim of this investigation was to define the long-term psychiatric outcomes of adolescent internalizing disorder in the general population, using data from ages 13 to 53 in a national birth cohort.

Results

Of the 3,279 cohort members in the sample, 46 (1.4%) were identified as having persistent internalizing disorder in adolescence, 231 (7.0%) as having single-episode internalizing disorder, and 3,002 (91.6%) as having no disorder.

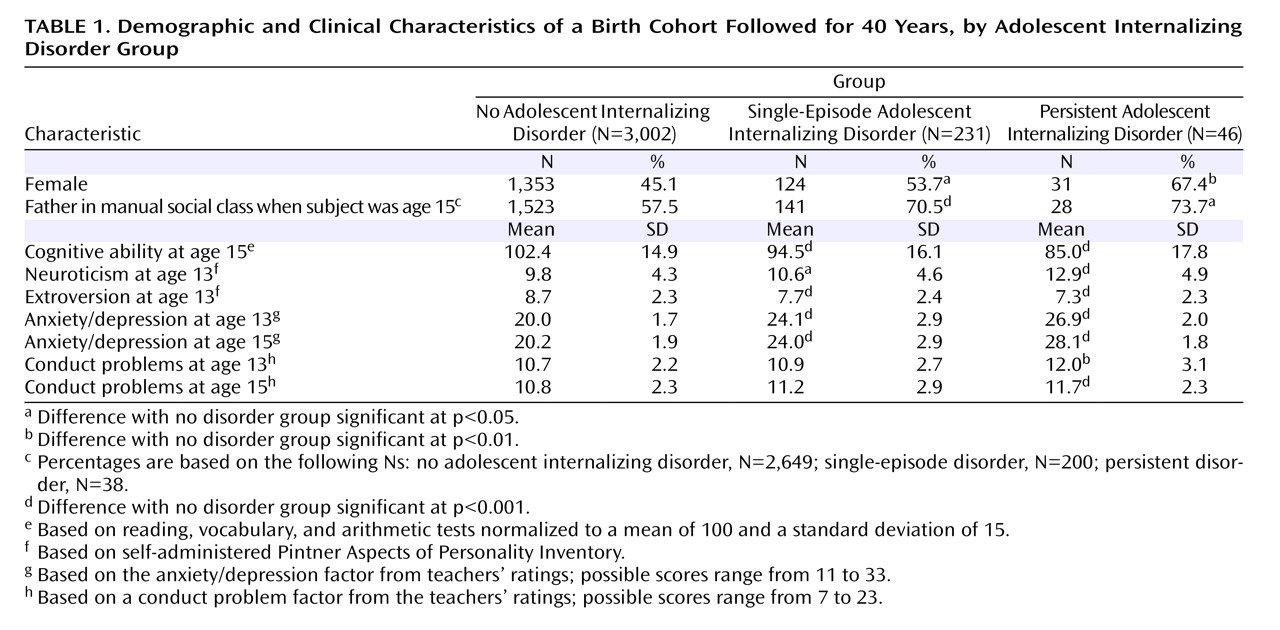

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups. Adolescents with internalizing disorder were more likely to be girls, to have a father from a manual social class, to have lower cognitive ability, to have a more neurotic and less extroverted personality, and to have conduct problems. All of these likelihoods were highest among adolescents with persistent disorder, and those with single-episode disorder were at an intermediate location between those with no disorder and those with persistent disorder.

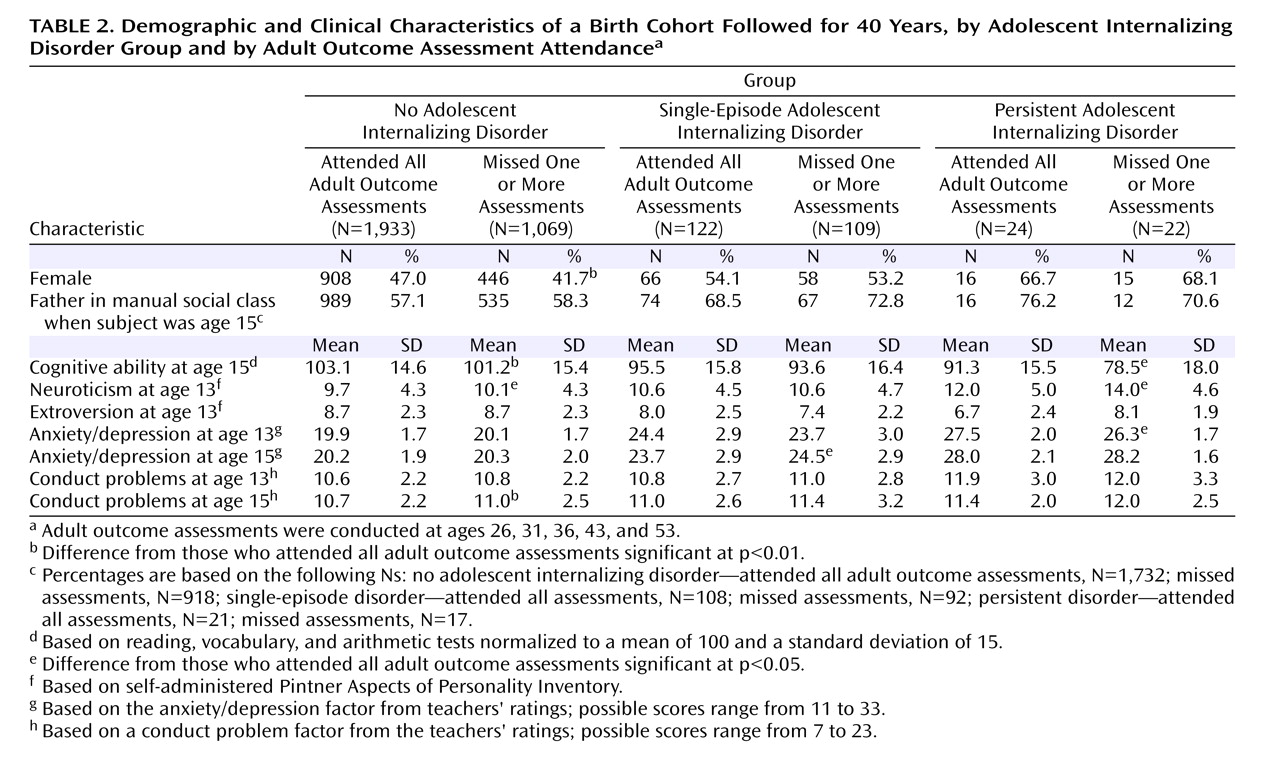

Table 2 compares those who provided information at all assessments in each group with those who missed one or more assessments. There were few significant differences between these two groups. Those who did not provide information at all assessments had lower mean scores on tests of cognitive ability and had slightly higher mean neuroticism scores; there were also some indications that they scored slightly higher on average on a scale measuring conduct problems. There were no indications that those who did not provide information at all assessments scored higher on average on scales assessing the presence of mental disorder compared with those who completed all interviews.

Mental Disorder in Adulthood

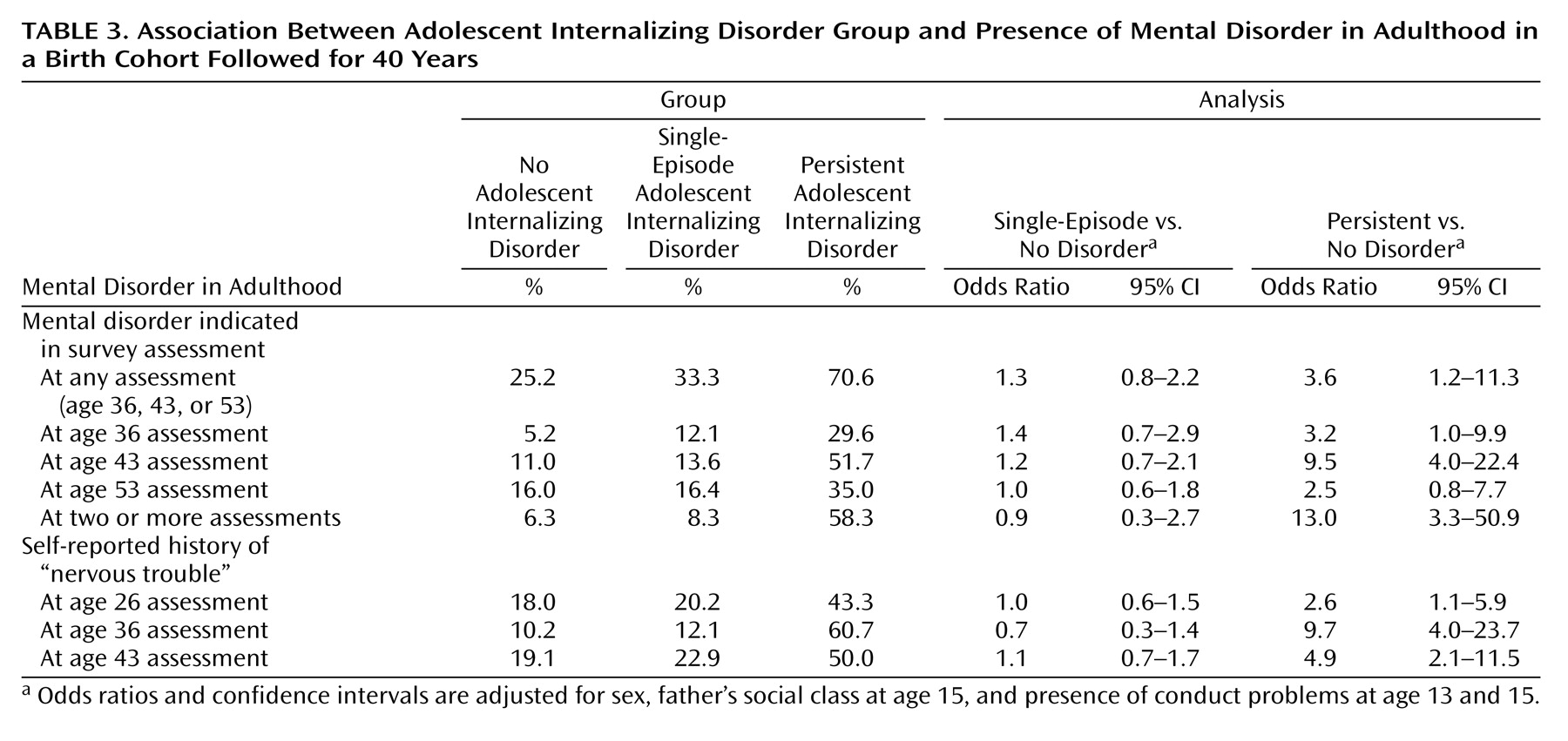

Adolescents with persistent internalizing disorder were significantly more likely than those with no disorder to have mental disorder in adulthood; no statistically significant differences were observed between the single-episode group and the no disorder group. While 25.2% of the no disorder group and 33.3% of the single-episode group had mental disorder at one of the adult assessments, 70.6% of the persistent disorder group had mental disorder at one or more of the adult assessments (

Table 3 ).

At ages 36, 43, and 53, the prevalence of mental disorder was not significantly higher in the single-episode group in comparison with the no disorder group (

Table 3 ). The prevalence of adulthood mental disorder in the persistent disorder group was significantly higher at ages 36 and 43 compared with the no disorder group. The prevalence of mental disorder at age 53 was elevated in the persistent disorder group, although this difference was not statistically significant.

In addition, adolescents with persistent disorder were significantly more likely to have multiple occurrences of mental disorder in adulthood; there was no significant difference between the single-episode group and the no disorder group (

Table 3 ).

Self-Reported History of “Nervous Trouble”

The frequency of reporting a history of nervous trouble at ages 26, 36, and 43 was not significantly different between the single-episode group and the no disorder group (

Table 3 ). However, it was significantly more common in the persistent disorder group at all three adult ages in comparison with the no disorder group, with odds ratios as high as 9.7.

Suicidal Ideation and Completed Suicide

Suicidal ideation was reported rarely at the three relevant enquiries (prevalence was less than 2% at ages 36, 43, and 53). Suicidal ideation was significantly more common in the single-episode group at age 36 (odds ratio=6.0; 95% CI=1.9–19.4) in comparison with the no disorder group, but not at ages 43 or 53. No significant differences were noted between the persistent disorder group and the no disorder group. Deaths by suicide were rare, with five suicides in the no disorder group, none in the single-episode group, and one in the persistent disorder group. The presence of one suicide among subjects in the persistent disorder group resulted in a significant increase in the odds of suicide in comparison with the no disorder group (odds ratio=13.5, 95% CI=1.5–118, unadjusted).

Physician Treatment for “Nerves”

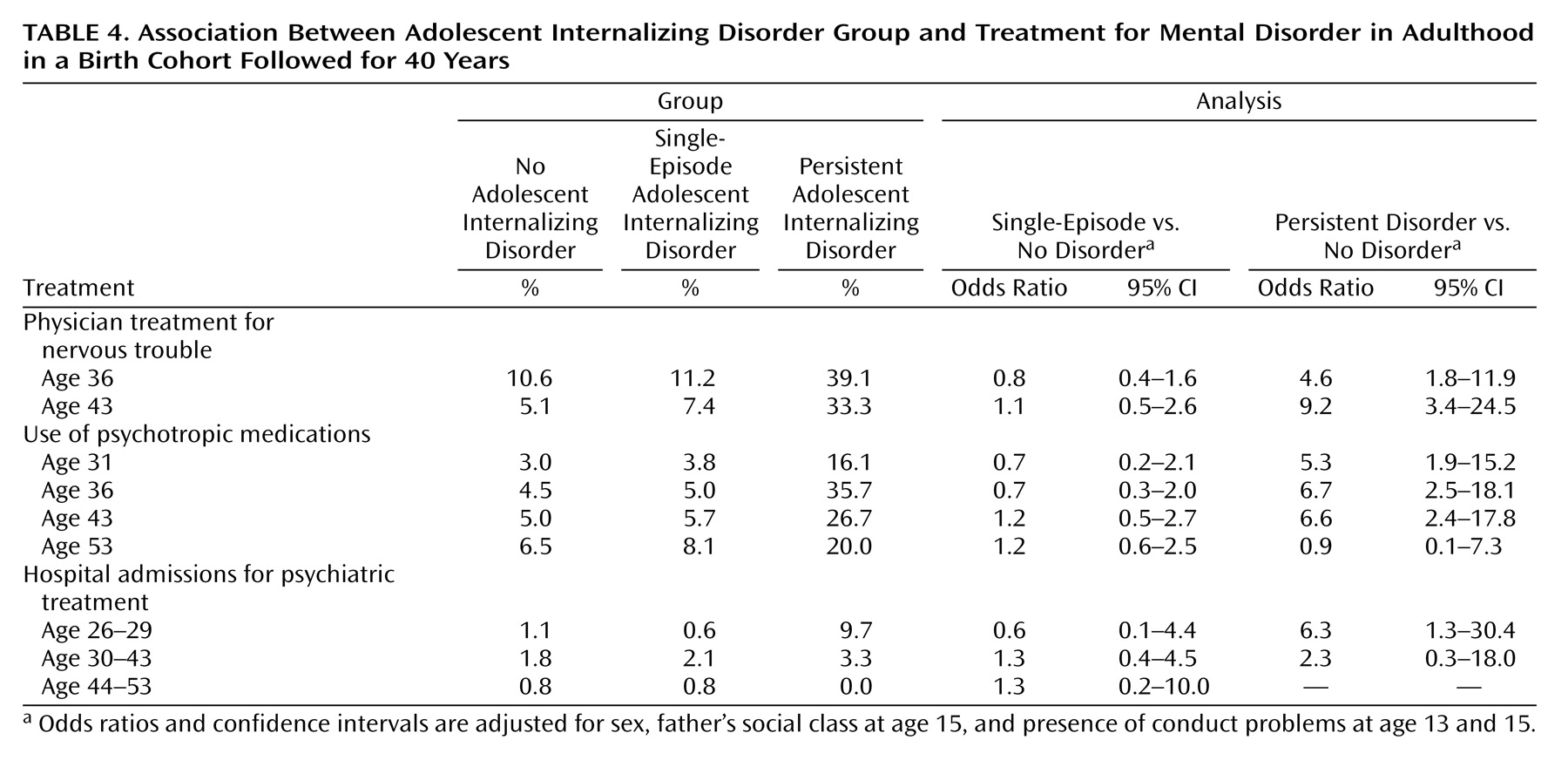

There were no significant differences in frequency of physician treatment for nervous trouble at ages 36 and 43 between the single-episode group and the no disorder group, but physician treatment for nervous trouble at these ages was significantly more common in the persistent disorder group (

Table 4 ).

Treatment With Psychotropic Medications

Use of psychotropic medication at ages 31, 36, 43, and 53 was not significantly different between the single-episode group and the no disorder group (

Table 4 ). However, in the persistent disorder group, the proportion using psychotropic medication was significantly higher at ages 31, 36, and 43 in comparison with the no disorder group, with odds ratios in the range of 5.3 to 6.7. Use of psychotropic medications at age 53 was not significantly different between the persistent disorder group and the no disorder group.

Hospital Admissions for Psychiatric Treatment

Hospital admissions for psychiatric treatment were relatively rare throughout the follow-up period (

Table 4 ). Subjects in the persistent disorder group were significantly more likely than those in the no disorder group to have admissions for psychiatric treatment between ages 26 and 29. There were no significant differences between the groups at other ages.

Discussion

In this prospective, population-based follow-up study, persistent or recurrent internalizing disorder in adolescence was strongly associated with poor psychiatric outcomes in adulthood, while episodic or transient symptoms in adolescence were associated with fewer negative adult outcomes. These associations remained consistent over a 40-year follow-up period.

The long-term outcome for adolescents who had persistent or recurrent internalizing disorder was markedly poor, with odds ratios for mental disorder in adulthood as high as 9.5 when compared with adolescents with no disorder. Prospective studies of adolescent depression have reported higher rates of depression in adulthood for those whose symptoms were more persistent in comparison with those who had more transient episodes

(35,

36) . Our study shows similar results and confirms them across several ages and several different outcomes, including questionnaire-assessed and self-reported mental disorder as well as physician treatment and use of psychotropic medications for mental disorder.

The outcome for adolescents with a single episode of internalizing disorder, however, was not as negative as expected. There was little indication of any increase in frequency of poor adult outcomes across numerous measures, including mental disorder, self-reported nervous trouble, physician treatment for mental disorder, and use of psychotropic medications, compared with adolescents who had no internalizing disorder. These results challenge those from several studies that found poor adult mental health outcomes for adolescents with depression

(8 –

14) and anxiety

(10,

15) .

There are several possible explanations for why our results differ from those of other studies. First, other studies did not stratify by duration of adolescent symptoms, which suggests that the association between adolescent depression and anxiety and poor adult mental health may be accounted for by adolescents with the most persistent symptoms. Second, several of the comparable studies used clinical samples of adolescents, who may be those most likely to suffer persistent symptoms.

A third explanation is that our study used teachers’ ratings of the adolescents’ mental health. Studies using the Rutter B2 scale

(37), in which teachers use a method similar to the scale used in our study to assess adolescent symptoms and behavior, have found that teachers may identify mental disorder in children more accurately than parents or the children themselves

(38) and that teacher-rated mental disorder more accurately predicts future mental disorder than mental disorder based on parent or child ratings

(39) . Nevertheless, it is possible that the outcome of teacher-identified adolescent internalizing disorder may differ from that of self-reported adolescent internalizing disorder.

A final possibility is that the adolescents with episodic mental disorder may have been misclassified. It is possible that these adolescents had other, unreported episodes and belong in the persistent disorder group. Alternatively, misclassification could have occurred as a result of regression to the mean between the two measurements in adolescence or of measurement error leading to some cases being classified as just below threshold when in fact they were just over the threshold; again, true persistent illness would have been wrongly classified as single-episode illness.

Misclassification tends to dilute observed differences between groups. This might explain why we found nonsignificant differences between the single-episode group and the no disorder group. However, one would expect a similar bias to exist in other, comparable studies. Furthermore, this effect would not explain why the persistent disorder group had a markedly worse prognosis than the other two groups; rather, the bias would have led to them to appear more similar.

While we obtained some mixed results on the question of whether adolescents who had a single episode of internalizing disorder had a higher risk of mental disorder in adulthood, it is clear that for the majority of these adolescents, the prognosis for adulthood was positive. Two-thirds of those in the single-episode group did not have mental disorder at any of the three adult ages at which they were tested. Furthermore, the prevalence of most mental disorder and psychiatric treatment outcomes at specific ages was less than 20%.

Mental disorder in early life, particularly depression, may differ according to age at onset. It has been suggested that even within the category of juvenile-onset depression, prepubertal-onset depression may differ from postpubertal-onset depression

(40,

41) . This theoretical framework has been supported by studies showing that the risk of poor adult mental health outcomes differs according to onset time of depression (prepubertal versus postpubertal)

(13,

40) . We did not have sufficient information to assess mental disorder in prepubertal childhood and were unable to stratify adolescents with mental disorder according to their onset age; thus, we may have combined two clinically distinct groups. We did compare adult outcomes for those with mental disorder at age 13 and those with mental disorder at age 15 and found few statistically significant differences (data not shown); however, this is unlikely to be a precise measure of child versus adolescent onset.

Most other follow-up studies of adolescent mental disorder have used DSM-type diagnoses in adolescence or adulthood, studying cohorts of adolescents with major depressive disorder, for example. Our cohort data did not provide us with precise enough information to make such diagnoses, which may limit our ability to compare our results with those of these other studies. Nevertheless, our results provide important information about the associations between severe internalizing disorder in adolescence and in adulthood.

A final limitation lies with sample attrition over the follow-up period, particularly among those who had adolescent internalizing disorder; almost half of these cohort members had left the study by age 53, a significantly larger proportion than the remainder of the cohort. This would introduce a bias if those who dropped out differed markedly from those who remained in the study. Analyses of those who left the study indicated few differences between those who completed all interviews and those who did not. Most important, there was no evidence that those who left the study were more likely to be those with more severe adolescent internalizing disorder. This suggests that those who stayed in the study should be representative of all the adolescents with internalizing disorder and that our associations were not biased.

In the face of these potential limitations, this study had several methodological strengths. The first is that the NSHD is a population-based sample representative of the population of England, Scotland, and Wales born in the post-Second World War period. The second is that the sample is large and allowed for follow-up of 277 adolescents with mental disorder, considerably more than most comparable studies. Third, because the NSHD is one of the oldest prospective cohort studies, it provides follow-up data much further into adult life than other epidemiological studies of adolescent depression. Finally, because the cohort members were born in 1946, the NSHD represents the postwar baby-boom generation that will be responsible for the imminent boom in the population of the elderly.

A remarkable aspect of this study is that assessment of mental disorder is based on data collected in 1959 and 1961, when clinicians widely believed that affective disorder did not exist in childhood and adolescence

(42) . Yet, by using such relevant historical data, we were able to identify subjects with internalizing disorder in numbers similar to those that would be expected today

(1 –

3) .

The results of this study suggest differing trajectories of mental disorder across the life course, with some adolescents with internalizing disorder proceeding to a life with persistent mental health problems while others conform to general population trends. Data of this type support a call for the incorporation of a longitudinal perspective into classifying phenotypes of mental disorder

(43) as well as investigations into causation. Ongoing prospective studies such as the NSHD are likely to continue to be important in this regard.