First scientifically described in 1946 by E.M. Jelliinek, an alcohol-induced blackout is an amnestic event during a drinking episode without loss of consciousness. During a blackout, the alcohol user may behave normally, yet have no recollection of events upon sobriety. Blackouts may be “complete” (en bloc) or “incomplete” (fragmented), sometimes distinguished by the ability to recall events with memory cues. The mechanism of this phenomenon is thought to involve alcohol's antagonism of the

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor, leading to inhibition of CA1 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus, resulting in a temporary disruption of the encoding step of memory formation (

1). Blackout history can provide important insight into a person's relationship with alcohol. Such history can be a source of exploration as a negative consequence of drinking when addressing ambivalence to change.

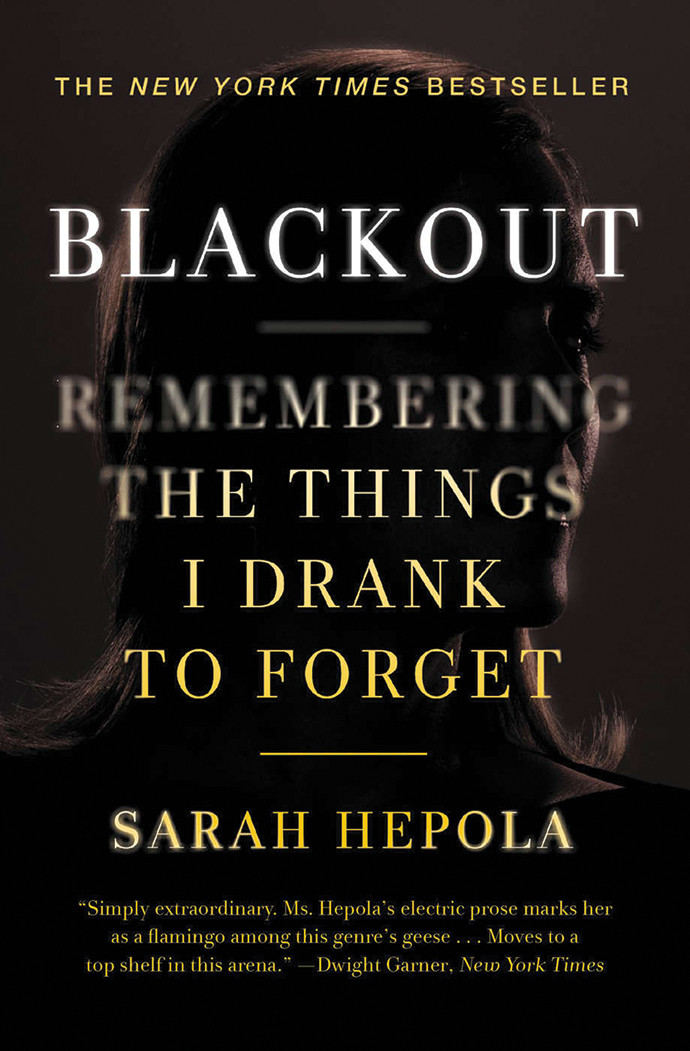

In her New York Times bestselling memoir Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget, Sarah Hepola describes several such blackouts in the course of her lifelong relationship with alcohol. Hepola's first taste came when she was just 7 years old sneaking sips of beer. She recounts an immediate intoxicating euphoria. Her first blackout came 4 years later when, unknowingly, she removed her clothes at an arcade and was discovered crying in a stairwell. Hepola's alcohol use escalated in college where excessive drinking was commonplace. Working as a writer in Dallas, and later in New York City, she had several anonymous one-time sexual encounters during blackouts. Hepola eventually got sober a few years before the memoire was published, and she discusses her temporary substitution of binge eating for binge drinking. She ends her book by discussing the challenges of dating, working, and socializing while sober, without using alcohol to cope.

I was drawn to Hepola's skillful use of self-deprecating humor to showcase her neuroticism. I found myself questioning how I would approach a patient like Hepola had she come to my office for substance abuse treatment. How could sobriety possibly compete with the physiologic comforts of alcohol? If using a motivational enhancement approach, I would likely feel the righting reflex, the temptation to correct or provide alternatives rather than guiding a patient through her ambivalence to change (

2). While helping Hepola cope during the early stages of remission, an insight-oriented approach might uncover a fear of being alone without her trustworthy relationship with alcohol. Consistent alcohol use during development dampens physiologic arousal surrounding stressful life events. Consequently, when a person stops drinking later in life, the therapist will need to provide support as the patient transitions to a life without a mind-altering drug (

3).

Unfortunately, Hepola does not delve into the factors that led her to eventually stop drinking. From the perspective of an early-career psychiatrist, it is helpful to postulate that the discomfort of blacking out eventually outweighed the comforts of drinking. As evidenced from the title of Hepola's memoir, understanding the influence of alcohol on memory may bolster our understanding of why our patients drink and help them to cope once they have achieved abstinence.