“Emotions can’t quit, genius!” (

1)

Although our species has described emotions for thousands of years, the neuronal labyrinth that forms them remains elusive. In early adolescence, striking changes take place as the maturation of cortical connections occur, affecting an individual’s ability to cope with, understand, and reflect upon such emotions (

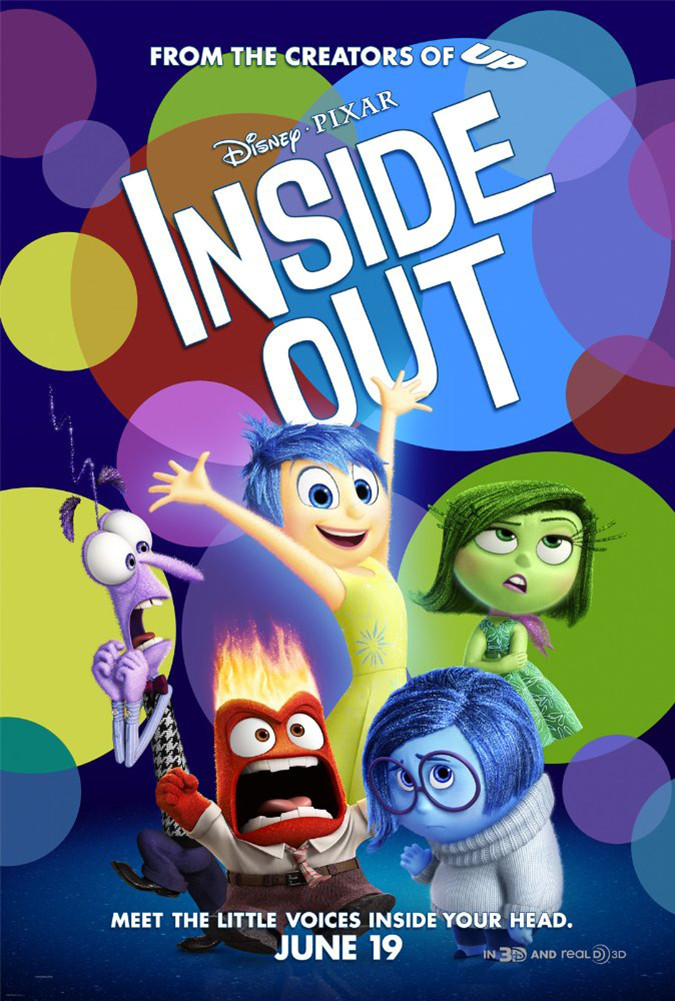

2). The recent children’s film

Inside Out, directed by Pete Docter, takes on the ambitious task of capturing this complexity in the mind of a preadolescent girl named Riley.

In the film, there are five emotions represented as distinct characters: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Disgust, and Anger. These emotions live in the mind’s “Headquarters” and have access to the main control panel, which dictates Riley’s affect and actions.

In the beginning of the film, we witness Riley’s first psychosocial stressor. Her family moves from Minnesota to California, where her father has accepted a demanding new job. Riley has difficulty adapting to her new home and forms her first important sad memory while crying in front of her new class. After Joy’s precarious attempt to prevent more sad memories fails, both Joy and Sadness are unwittingly sucked into a memory tube, leaving them lost in Riley’s brain.

The film follows Joy and Sadness as they find their way back to Headquarters, taking the viewer through Riley’s stages of development. Viewers feel sadness themselves as Riley’s imaginary friend Bing Bong—reminiscent of her preoperational stage—sacrifices himself to propel Joy toward Headquarters and wastes away in the Land of Forgotten Memories. Riley, who grows apathetic without Joy and Sadness in Headquarters, makes an attempt to run back to Minnesota. The film closes with Sadness returning Riley’s important memories and subsequently teaching Riley about the importance of incorporating the entire spectrum of emotions, bringing her back home to the warm embrace of her family.

Inside Out achieves the impressive feat of depicting emotions in a way that is accessible to young children. More importantly, the film demonstrates the benefit of expressing emotions, as well as the dangers of repressing them.

I couldn’t help but think of my own patients while watching this film. Although Riley has an unremarkable developmental history, no medical or psychiatric problems, and a strong support system, she experiences difficulty coping with periods of transition and stress. Our younger patients face additional adversities: they struggle with neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disabilities, autism, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. As psychiatrists, we are challenged with processing our own versions of Joy, Sadness, and other emotions with children who have experienced trauma, bullying, or unstable family structure.

Experiences in early life are thought to be a source of psychopathology by many highly regarded psychoanalysts. Riley’s resilience equips her for the upcoming conflicts she may experience in puberty. Inside Out implores us to make this a reality for our own young patients, perhaps by encouraging acceptance of the complete spectrum of their emotions, communicating the danger involved in restricting them, and realizing the same emotions connect us all to one another.