Cyclic vomiting syndrome is a debilitating clinical syndrome. It is characterized by intense, recurrent, intractable nausea and vomiting episodes lasting for hours to days, interspersed with symptom-free intervals that can last several months. It was first described in English pediatric literature in 1882 by Samuel Gee, who delineated symptoms as “fitful or recurrent vomiting” (

1). Cyclic vomiting syndrome was considered a pediatric functional gastroenterology disorder with a 0.04%–2% prevalence (

1). Increasingly, cyclic vomiting syndrome is becoming recognized in the adult population; however, the prevalence in adults remains unknown (

1). The exact etiopathogenesis is unknown, and the disorder is associated with migraines, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroendocrine abnormalities (

1).

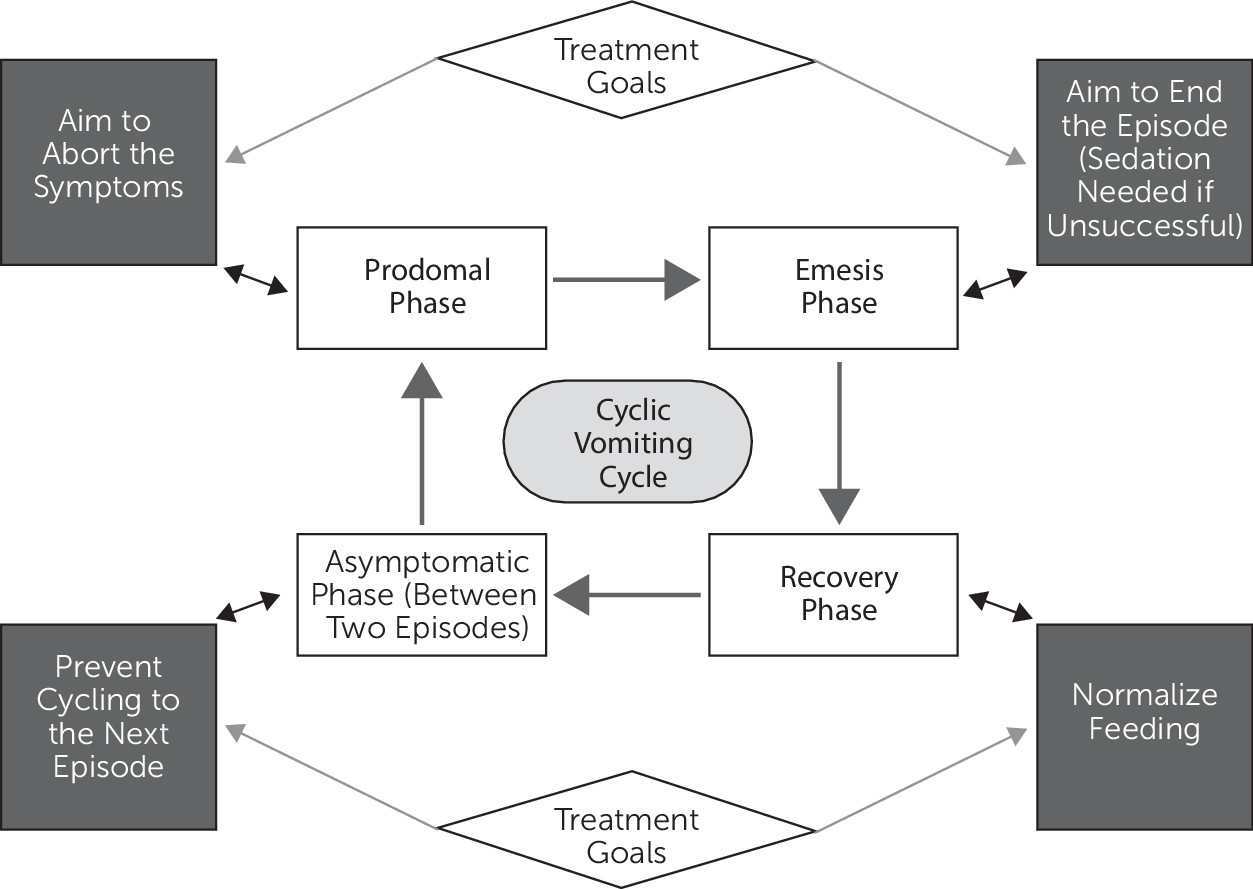

Rome III diagnostic criteria are used for cyclic vomiting syndrome diagnosis. Per Rome III classification, patients have stereotypical vomiting episodes with acute onset (

2,

3). The episodes occur multiple times in a year. Individuals with the disorder are usually asymptomatic between episodes. They classically experience intense nausea and vomiting after initially being asymptomatic. The most debilitating vomiting period may manifest with up to 20–30 vomiting episodes per day (see

Figure 1) (

4). Psychiatric comorbidities in cyclic vomiting syndrome are often unknown, and very few prospective studies are available in the literature (

4). Anxiety disorders and depressive symptoms are the most common psychiatric findings among patients (

4). The present article is a review of the literature, with emphasis on psychiatric comorbidities.

Discussion

Psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety and depression are observed in the prodromal phase and the acute emetic phase in cyclic vomiting syndrome (

5). The most commonly associated psychiatric disorders include anxiety disorders and mood disorders (

6). Less frequent associations are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and somatic symptom disorder (

7). A pilot study among children and adolescents with cyclic vomiting syndrome reported that approximately 54% of adolescents met cutoff criteria for anxiety disorders, the most common being generalized anxiety disorder and specific phobia (

4). Approximately 15%–18% met criteria for major depression and dysthymia (

4).

The etiology of cyclic vomiting syndrome remains unknown. It is difficult to delineate whether anxiety and/or depression is the cause or the result of this syndrome. However, in one study, a significant association between anxiety and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents was found, with lower quality of life reported with higher level of anxiety (

8). In another study, depression was found to be comorbid but not as common as anxiety (

4). In a study of 31 participants, anxiety was noted in 84% of the study population and depression in 78% (

7). Overall, psychiatric comorbidities have high impact on quality of life. Panic disorder is the most common form of anxiety in patients with cyclic vomiting syndrome (

7). Symptoms of panic disorder usually respond to lorazepam (

7). Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults is typically indicated by abdominal pain, higher rates of anxiety and depression, and rapid gastric emptying (

1), as well as successful suppression of attacks by chronic amitriptyline therapy (

9). Amitriptyline is thought to modulate vomiting through its anticholinergic and serotonergic effects (

10). However, providers need to be aware of its cardiotoxic potential in overdoses (

10).

Management of cyclic vomiting syndrome and its associated psychiatric comorbidities includes pharmacological and psychosocial interventions. Current literature suggests that various pharmacological agents, such as valproate, barbiturates, cyproheptadine, amitriptyline, propranolol, erythromycin, and mirtazapine, may be beneficial for prophylaxis (

11). Intravenous fluids, ondansetron, and sedation with intravenous lorazepam may potentially provide relief during the vomiting phase (

12). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with a multidisciplinary approach has been favorable in children, but evidence is lacking in adults (

13). A behavioral approach in combination with amitriptyline has the potential of increasing remission rates (

13). The role of marijuana use remains controversial (

14,

15). For example, marijuana use is reported to be associated with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, which also has vomiting as its major symptom. However, the differentiating feature is that in cyclic vomiting syndrome, an individual has no vomiting between episodes, and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is associated with nausea and vomiting after each cannabis use (

15). Contradictory to reports of increased emesis with cannabis use, a study based on a survey of cyclic vomiting syndrome patients found that most of these patients reported some improvement in nausea and vomiting symptoms with cannabis use, and per the hypothesis in this survey-based research, chronic marijuana use might have antiemetic effect (

14). Additionally, hot water bathing was found to be associated with marijuana use, although hot water bathing itself was observed in both the marijuana-user group and the non-user group, and the clear effects are not known (

14).

Lastly, it is important to consider the health care cost associated with cyclic vomiting syndrome. In a recently published article summarizing health care access and utilization reports per the 2010–2011 National Inpatient Sample database analysis, the diagnosis of cyclic vomiting syndrome was associated with an overall cost approximation of $400 million over 2 years (

16). The average hospitalization frequency is not known.

Conclusions

Cyclic vomiting syndrome is a common, idiopathic, functional disorder that is difficult to treat due to lack of standard diagnostic and treatment guidelines, and it requires collaborative care between medicine and psychiatry. There is a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders comorbid with cyclic vomiting syndrome among both children and adults. These findings strongly suggest the need for careful and detailed psychiatric screenings in patients who have this disorder. If comorbid conditions are left untreated, the consequences may have significant medical and/or mental health impact, which could lead to social, family, or academic impairment. While amitriptyline may be beneficial in some individuals, further studies are needed to confirm its true efficacy. The cardiotoxic potential and side-effect profile of amitriptyline is an important limitation of use of this drug, which providers must keep in mind. Long-term outcomes could be understood with prospective studies with larger sample sizes. The lack of awareness of cyclic vomiting syndrome among health care professionals presents a great deal of challenge in early diagnosis and treatment.