According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), around 70% of physicians in the United States have received some of their training with the VA. A total of 178 of 183 U.S. medical schools are affiliated with the VA, and 43,565 medical residents, 24,683 medical students, and 463 advanced fellows received some or all of their clinical training within the VA system in 2017 (

1). Despite this training, most clinicians do not feel adequately prepared to provide high-quality care for veterans. In a recent study, only 13% of mental health providers met readiness criteria for culture competency in treating veterans (

2).

To better serve this population, it is imperative that clinicians understand military culture. The present article provides clinicians with useful information to consider when treating active-duty service members and veterans.

Individual Experience

The military experience of all veterans is unique. Their branch of service (Marine Corps, Navy, Army, Air Force, or Coast Guard), their rank, their job (referred to as their military occupation specialty [or MOS]), and the period during which they served (World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Gulf War, Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom, or "peacetime") all have an impact on their experience during active duty and after leaving the service.

Veterans’ rank has a great impact on their individual experience. Military ranks differ by branch and are compared between branches by pay grade (enlisted ranks, E1–E9; officer ranks, O1–O10). Veterans will often make statements such as, "I was an E-5," rather than saying, "I was a sergeant" (in the Army or Marine Corps), or "I was a petty officer second class" (in the Navy or Coast Guard). Enlisted personnel make up approximately 82% of active-duty military service members, most of whom enlisted shortly after completing high school. This is important to recognize, because while their civilian peers were leaving home for college or their first job, the enlisted veteran may have been leading troops or fighting in combat.

An officer is an individual who obtained a commission by having completed at least a bachelor’s degree and graduating from an officer candidate school (referred to as an OCS) or military academy. Officer ranks tend to be more familiar to the civilian population (e.g., lieutenant, captain, colonel, admiral, or general), but titles differ between the different branches of services. Because the majority of U.S. veterans served in the enlisted ranks, usually ≤4 years, it would benefit clinicians to become more familiar with the E1–E5 ranks.

Shared Experience

There are many things that all service members have in common (see box). Sacrifice is at the top of the list of their shared experience. Time away from family and friends, long hours of duty, and very hard work are just a few of the enormous obligations that veterans have during their service.

BOX. Common Traits Among Service Members

Ironically, service members forfeit many of the freedoms that they fight to protect. They give up a piece of their individuality to become a part of something larger than themselves. While serving in active duty, uniformity is the rule: dressing the same, speaking the same, and behaving the same. The right to free speech, the right to bear arms, protection from illegal search and seizure, and the right to a trial by jury are all relinquished. Additionally, unlike in civilian jobs, once a contract to join the military is signed, it cannot be freely withdrawn by the signee. Without a proper discharge, a service member can be criminally charged with desertion.

Despite all of the privileges that veterans give up, working as part of a team and being able to rely on those around them inspires a sense of pride, belonging, loyalty, and brotherhood known as esprit de corps. This is why many veterans feel a sense of comfort and connection with other veterans, even with those from different branches of service or from different eras. "I got your six" is a way of saying "I’ve got your back," which embodies this idea.

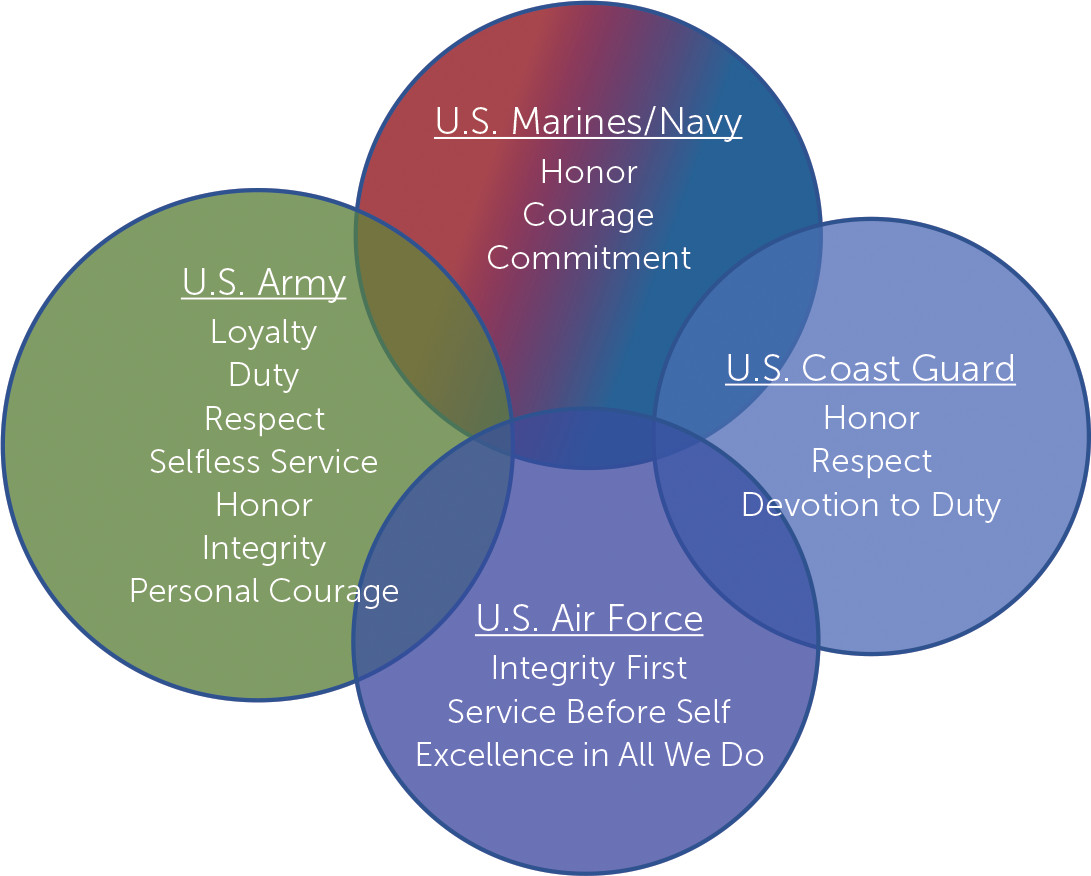

In the civilian world, an individual’s beliefs and values can be ambiguous and may change over time. In the military, values are spelled out and explicitly taught from the beginning. Each branch of service holds its own core values (

Figure 1). However, despite differences in verbiage, honor, courage, duty, and service above self are common values shared by all service members. These traits and ethics epitomize holding oneself to a higher standard and remain with the veteran over the course of a lifetime.

At some point in most veterans’ experiences, they are confronted with their own mortality. By joining the military, they put themselves in harm’s way. They may have considered it when they signed the contract, or they may not have appreciated it until they were "down range" with rounds screaming past. Dark humor, with morbid jokes about death, are ubiquitous in the military. Whether serving during a time of war or peace, killing and dying in service to one’s country are common themes. Speaking flippantly about death is not a morbid preoccupation, it is a way of coping with this overwhelming burden. Thus, it is important for clinicians to note that a veteran admitting to thoughts about his or her own death may not necessarily be suicidal ideation, it is often a continuation of this mentality. These thoughts are often hidden from family and friends as well as from clinicians due to fear of judgment. This fear of judgment is what may prevent veterans from talking openly with civilians and from seeking professional help. Discussing the veteran’s thoughts about death, if approached from an empathetic and nonjudgmental stance, can bolster trust and expose possible internal conflicts, including moral injury.

How to Approach Veterans

The following bullet points are suggestions for clinicians on how to approach veterans in the clinical setting. (Additional resources are presented in

Table 1.)

•

Ask questions. The military has a lot of abbreviations and acronyms, as well as jargon and slang. Asking the veteran to explain military terminology will show interest, and it can help build rapport and lessen resistance.

•

Listen. All veterans have a unique story about why they joined the military, what they did while serving, and how they feel about it. A clinician can show interest in the veteran as an individual by asking questions such as, "What branch were you in?", "When did you serve?", "What was your MOS?", "Where were you stationed?", and "Were you deployed?" Listening to the veteran’s story will help to establish rapport and help to put the veteran at ease. It is crucial that veterans’ first experience with a clinician be positive and welcoming, even at the expense of having to schedule a follow-up appointment to address all of their concerns.

•

Show concern. When a veteran says "I’m fine," it does not mean that he or she is not experiencing psychological distress or medical illness. Most of military training teaches men and women how to suppress their feelings. "Suck it up" and "rub some dirt in it" are common responses to complaints about discomfort, illness, or injury. When the veteran says, "I’m fine," he or she is often having difficulty admitting any hardship. This is an opportunity for the clinician to show empathy and concern. This is when the clinician should put down the clipboard, turn away from the computer, look the veteran in the eyes and say, "I am here for you." "How can I help?"

•

Build trust and respect. Never say "I understand" to a veteran. This phrase, even when said with empathy, may cause a veteran to withdraw or become angry. Respect and trust can be elicited with other empathetic statements or questions, such as "How was that for you?" or "I can’t imagine what that was like for you."

•

Understand trauma. Not all trauma is military or deployment related. Service members carry the wounds and traumas of their lives with them into the military. Moreover, stress is an everyday part of military life, long before deployment to combat. Traumatic events, including sexual trauma and losses, can occur on a military base just as easily as on the battlefield. These traumas can sometimes be more difficult to heal, because they are unexpected. Ask veterans about painful experiences they may have had apart from deployment or before enlisting.

•

Refrain from judgment. Servicemen and women have been put in situations where split-second decisions dictate dying versus going home to their families. Postdeployment, these decisions often weigh heavily on their minds and their conscious. This is referred to as moral injury. It is not helpful for the clinician to express his or her opinions or moral judgments. The clinician should be supportive and empathetic while the veteran works through these issues.

•

Thank the veteran with sincerity. "Thank you for your service." Although well intended, this phrase has been overused and can sound shallow and contrived. Instead, clinicians should aim to be more spontaneous and less automatic. "Welcome back," "Welcome home," or even just "Thank you" can give the intended message without ringing hollow.

Conclusions

The topics discussed in this article are merely the tip of the iceberg, intended to provide clinicians with a glimpse into military culture. Being aware of this information is a first step toward better serving the veteran population.

Key Points/Clinical Pearls