Functional neurological symptom disorder (FNSD)—formerly conversion disorder—is a disease characterized by symptoms that are suggestive of a neurological condition but that are incompatible with the pattern of a recognizably organic cause of neurological dysfunction (

1). The condition has a long history, with the name "conversion disorder" originating from Sigmund Freud and Josef Breuer’s (

2)

Studies on Hysteria, originally published in 1895. Understanding of the condition has greatly advanced since that time.

One of the most characteristic associations with FNSD is recent physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect preceding the onset of symptoms (

3–

5). However, since publication of the DSM-5, diagnosis of the condition no longer requires known antecedent trauma (

1). Indeed, a meta-analysis of published studies with quantitative reporting of FNSD cases found that only 49% of patients reported a traumatic stressor (

4). Furthermore, although the classical model of the condition suggested early childhood trauma as being of particular importance, an analysis by Spinhoven et al. (

5) of patients with conversion pathology determined that recent physical abuse—as was present in the case presented here—had the strongest association with the condition. This internal conflict can manifest as a wide constellation of symptoms, which can pose significant challenges to clinicians. The aim of this report is to present a case of dysautonomia-predominant FNSD.

Case

A 23-year-old woman presented to a hospital emergency department with a 3-week history of sudden-onset sharp back pain originating between her shoulder blades and radiating to her legs bilaterally. One week prior to arrival her symptoms progressed to multiple episodes of bowel and bladder incontinence and weakness of the right lower extremity. She reported that her episodes of fecal incontinence prompted her to seek medical treatment, as she had become unable to go to work for fear of having an episode of incontinence. She reported that this aspect of her illness was most concerning to her. This presentation was initially concerning for a spinal cord syndrome, particularly because of the patient’s recurrent incontinence. Organic myelopathy was, however, not supported by further evaluation.

On physical examination, the patient lacked a sensory level or dermatomal pattern. Lasègue’s maneuver, in which the patient’s straightened leg is raised while the patient is supine, did not produce any pain. Lhermitte’s sign was similarly negative, as no shock-like sensation was produced by neck flexion. Hoover’s sign, in which the patient is instructed to raise her unaffected lower extremity against resistance while an examiner inspects for the presence of involuntary extension at the hip of the affected extremity, was also negative in this patient. Of note, Hoover’s sign—often used to help diagnose FNSD—is often negative in patients presenting with only mild weakness (

6), as relatively strong synergistic contraction of the extensor muscles of the effected leg would be anticipated in both organic and functional causes of minor limb weakness. Sensory examination revealed qualitative changes in vibration and light touch bilaterally in the lower extremities. No signs of traumatic spinal injury were noted on examination or in her history.

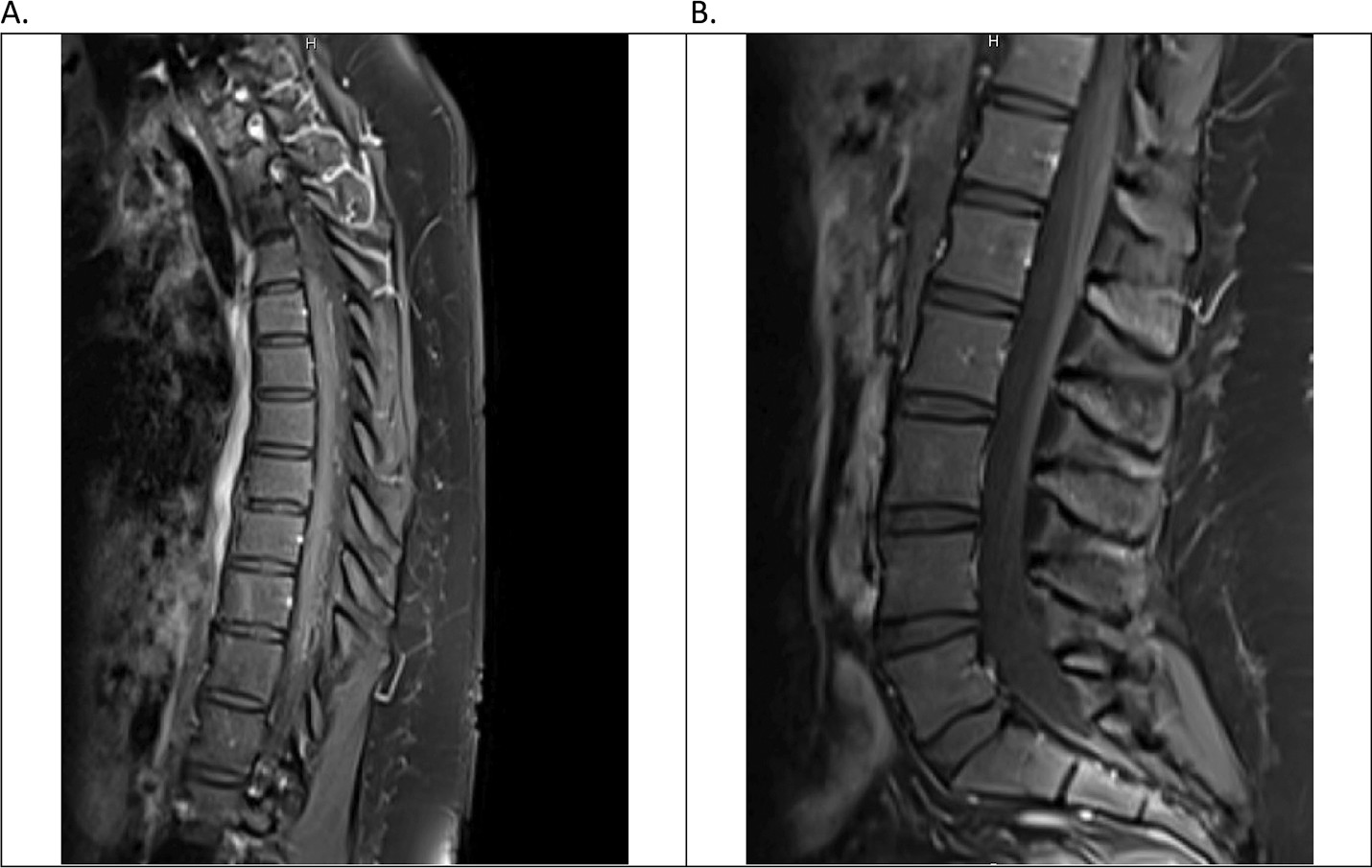

Contrast magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s spinal cord (

Figure 1) revealed no evidence of organic disease. Laboratory studies (

Table 1) were not consistent with findings of an established neurological condition. The only significant abnormality was in the patient’s elevated sedimentation rate; however, this test is nonspecific. Given the patient’s unremarkable C-reactive protein levels and the failure to note evidence of inflammatory pathology on imaging, this abnormality was considered noncontributory. The patient’s vital signs were all within normal limits throughout her hospital stay. Extensive investigation of the patient’s history revealed no significant family or personal history of relevant neurologic disorders. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation.

A psychiatric etiology, however, was more thoroughly considered after it was discovered that the patient had recently been the victim of physical assault at the hands of her significant other. In addition to the assault, several days before arriving at the hospital, her boyfriend threatened to "kill [the patient] with a hatchet." The patient at the time of arrival in the emergency department was continuing to live with her boyfriend because she lacked an alternative place to reside, having relocated to the area 3 months before from a different state. She admitted feeling overwhelming stress associated with this situation but had not connected it with her current medical condition.

Formal evaluation by the patient’s neurology team found no identifiable causes of the patient’s illness explainable by organic neuropathology. Although it is possible that a neurologic explanation may have been missed, in light of her recent severe psychological stressors, a psychogenic etiology was preferred. Ultimately, the patient elected to decline further assistance and chose to return to her current living situation. The patient was informed that her recent stressors could have been responsible for her condition; however, she was unable to be seen for a psychiatric evaluation prior to leaving the hospital. The patient did not appear for outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

Several hallmark findings are frequently associated with FNSD, particularly psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES), weakness, sensory changes, and blindness (

6). However, a functional etiology can be behind a wide array of seemingly neurological presentations. A cohort study of patients with neurological complaints in outpatient neurology clinics found that 18% had symptoms that could not be explained by organic neurological disorders (

7). Moreover, 26% of patients with identifiable neurological disease had additional symptoms that could not be attributed to their diagnosis or to any other organic disorder (

7). A separate investigation in the United Kingdom found the highest prevalence of FNSD patients not in neurology clinics but rather presenting initially to gynecologists (

8). As such, clearly the ability to identify and manage these patients is of concern to all clinicians regardless of specialty.

Identifying a patient with FNSD, however, has certain unique challenges—the foremost being how similar the presentation of the condition is to other neurological complaints, as well as how variable these complaints may be. In a study of 107 patients, Stone et al. (

6) found that patients frequently had functional complaints apart from PNES, weakness, and sensory changes. Among these patients, 49% experienced gastrointestinal symptoms and 28% experienced bladder-related symptoms. However, these symptoms are not classically regarded as part of FNSD in the same way that PNES is. Accordingly, patients for whom these more autonomic symptoms predominate can be more easily missed, because they do not match the prevailing archetype of the disorder even though such symptoms occur with relative frequency. Recognizing these findings as consistent with not just organic but also functional neurological symptoms is essential for establishing an accurate picture of what a patient with FNSD might look like in a clinical setting.

FNSD by its nature does not conform to the established patterns of neurological disease and cannot be mapped onto the distributions of specific nerves or dermatomes. One possible remedy for this dilemma of recognizing FNSD is to broaden the paradigm. Although visceral neurologic impairments have been previously documented in both case studies and more large-scale investigations (

6,

9–

12), they continue to be regarded as uncharacteristic of FNSD (

9). This is perhaps because reports of these findings remain infrequent, despite evidence suggesting that their prevalence is much higher than the reports would indicate (

6,

12). Reported autonomic symptoms range from sialorrhea (

11), urinary retention (

12), and vomiting (

9) to urinary and fecal incontinence, as reported in this case. However, the extent to which dysautonomia occurs and the specific ways that it can present in FNSD remain unstudied. Future investigations are needed to better understand this phenomenon.

The patient in this case was suffering from pain, paresthesia, and weakness for weeks prior to seeking care. It was not until her life was disrupted by the visceral manifestations of her illness—those most poorly recognized—that she was motivated to seek help. This both highlights the importance of not minimizing these autonomic deficits and underscores a problem with FNSD treatment in general. A delay between onset and initiation of treatment is a known poor prognostic indicator for this disorder (

9,

13). The prognosis of the condition is highly variable, with some cases resolving spontaneously without intervention within 2 weeks and others persisting for months to years (

13). In general, a poorer prognosis is associated with more severely disabling symptoms at presentation (

13).

To prevent these outcomes, it is imperative to begin treatment as soon as possible. The accepted strategies for treating FNSD are frequently multimodal, with providers offering targeted physical therapy in conjunction with psychotherapy (

13,

14). Use of psychotropic medications, specifically antidepressants and anxiolytics, has not demonstrated clear efficacy in the treatment of FNSD, and prescribing of these medications should be done judiciously based on psychiatric comorbidities (

14). Ultimately, both identification and treatment of FNSD can pose substantial challenges for even diligent clinicians. As such, it is crucial that providers understand the place that dysautonomia has in relation to FNSD in order to best care for this population.